All images courtesy of Tom Werman/Getty Images

By Andrew DiCecco

[email protected]

In the first segment of my two-part interview with renowned record producer Tom Werman, we discussed Tom’s formative years and subsequent transition into the music industry, successful signings as well as the ones that ultimately eluded him, and honed in on his work with Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, and Mötley Crüe.

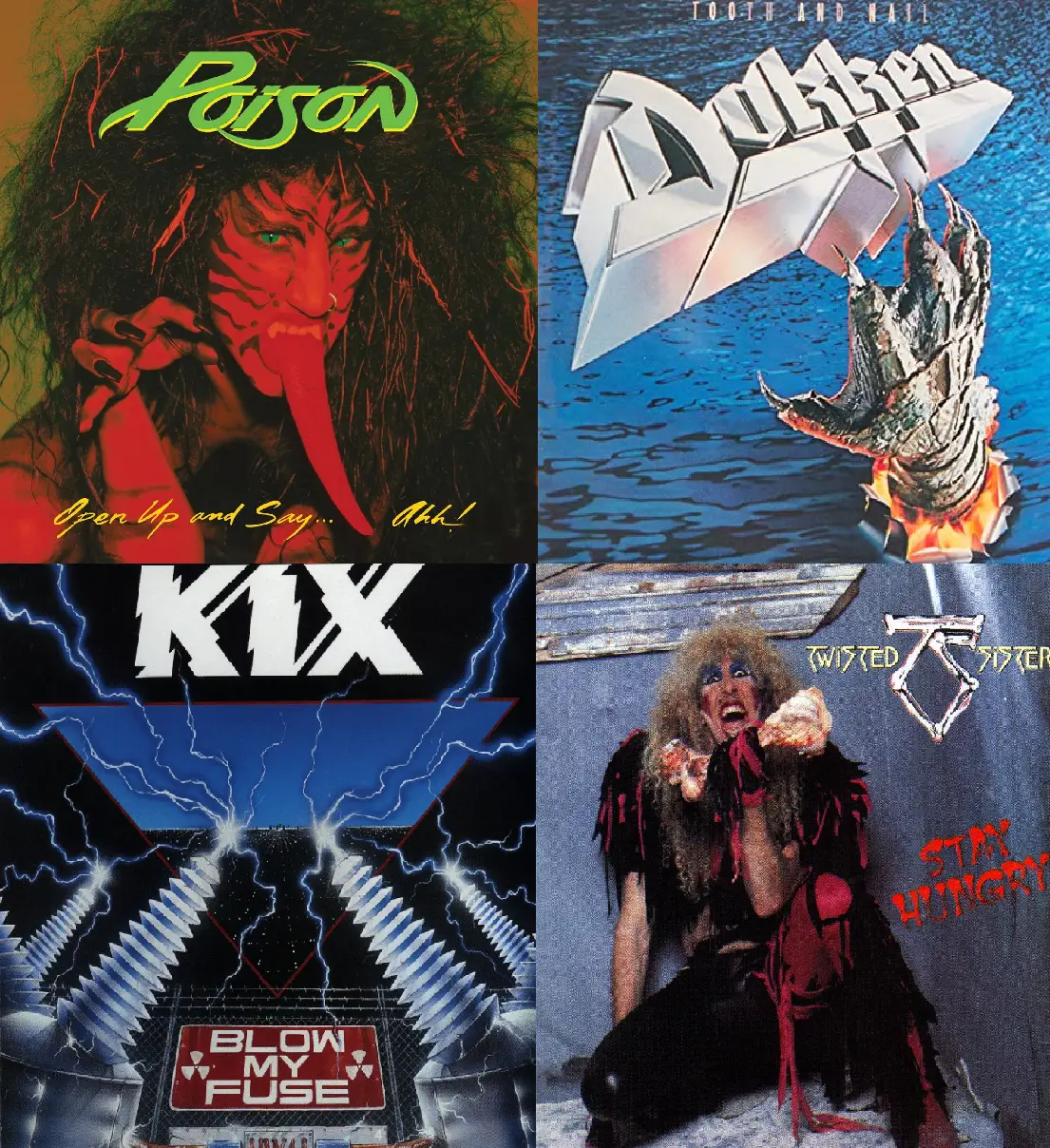

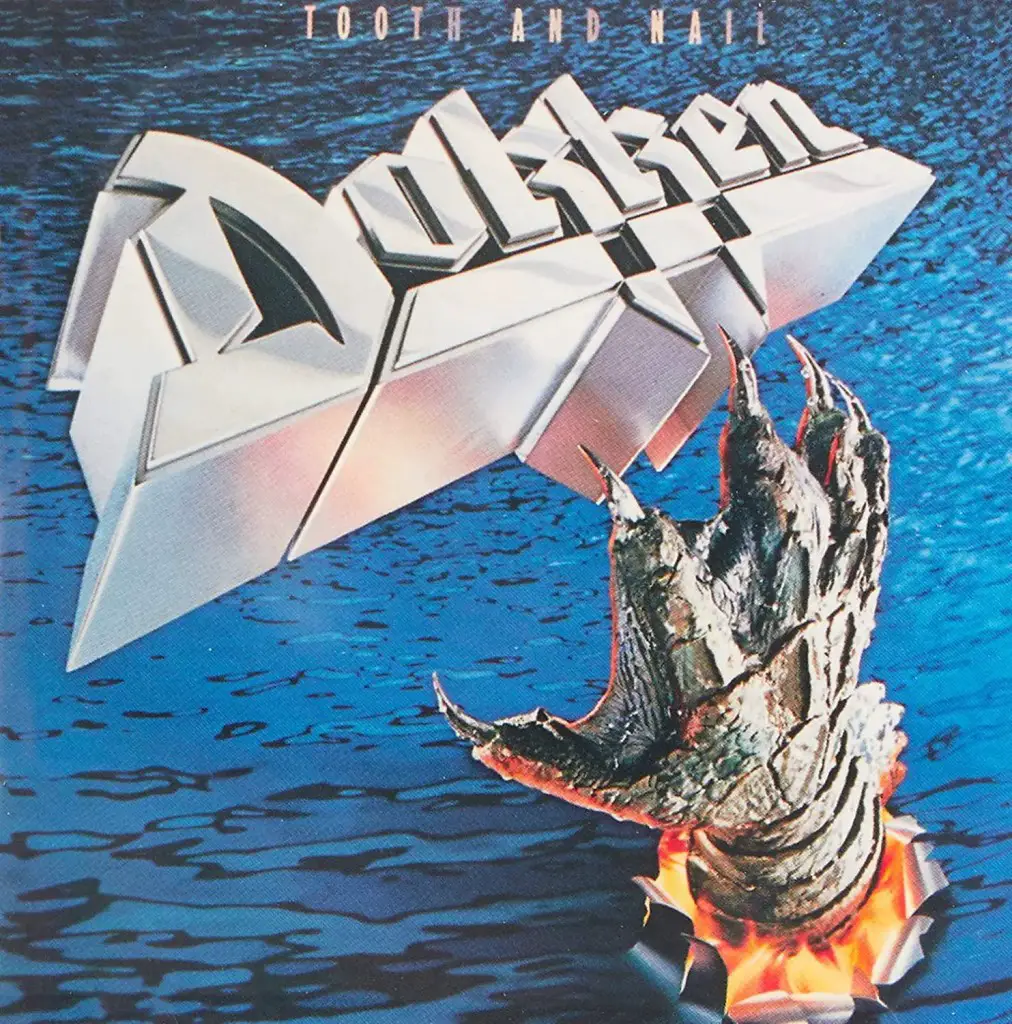

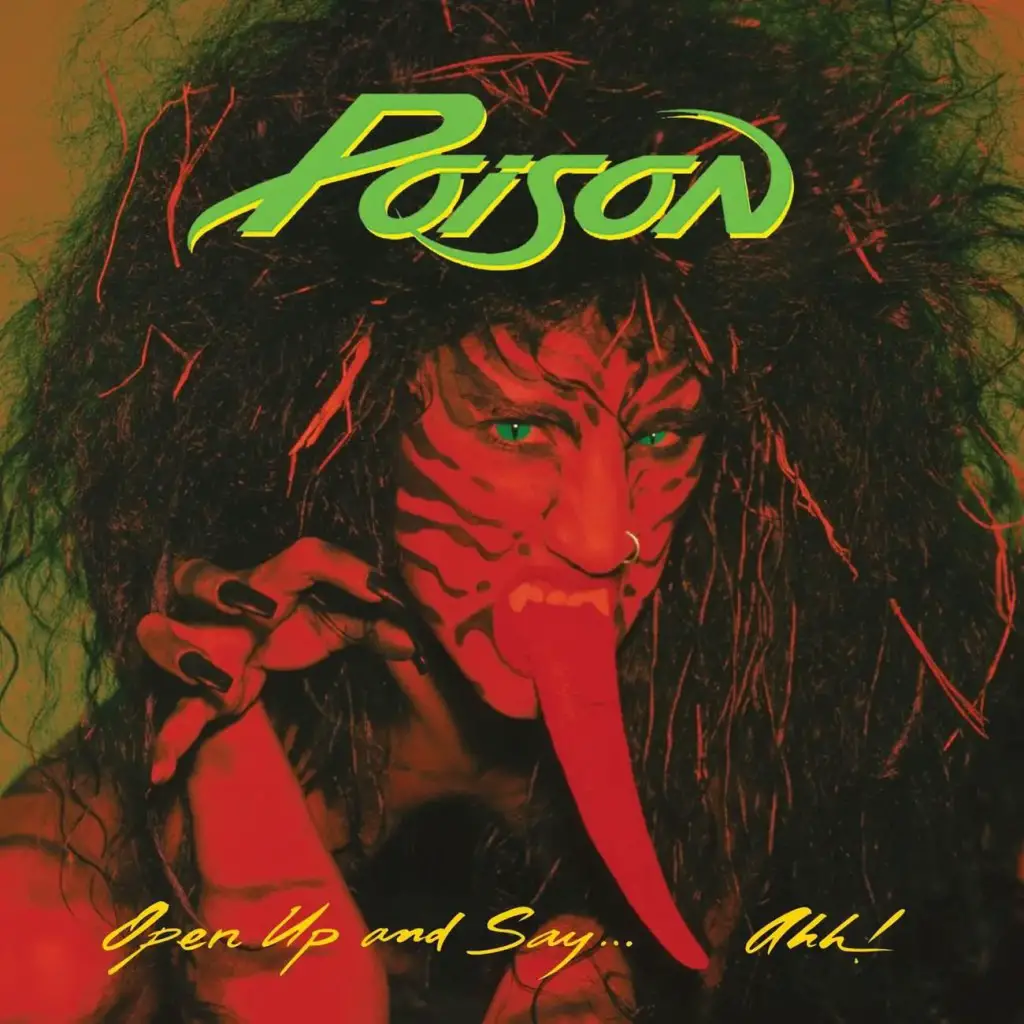

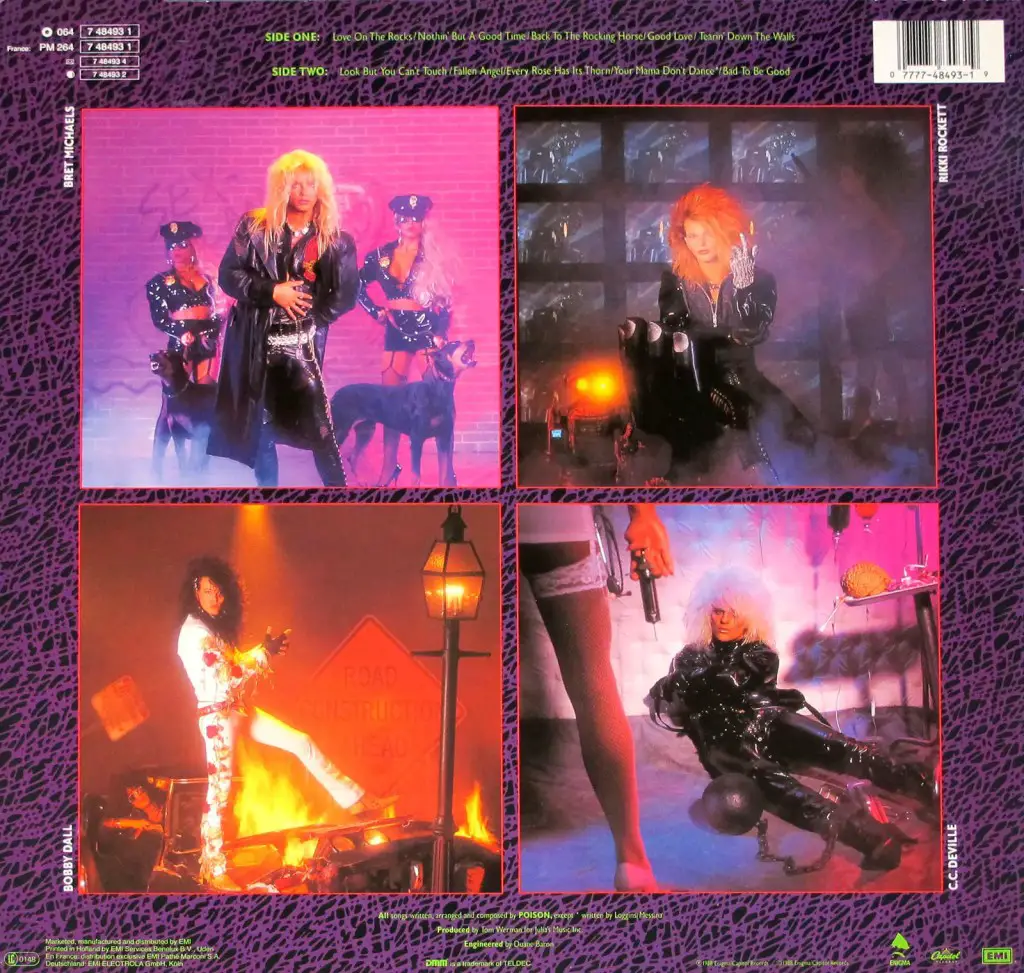

While Tom’s lengthy career cannot be fully explored in two one-hour Zoom sessions, some of the topics we touch upon in this second and final installment include his work with Twisted Sister, Dokken, Poison, KIX, his approach to power ballads, navigating the tumultuous musical shift of the 90s as a rock producer, and what he’s been up to since leaving the music industry twenty-one years ago.

Andrew:

As we transition from one decade-defining record to another, I wanted to turn the attention to the recording of Stay Hungry, Twisted Sister’s 1984 multi-platinum effort that has proven to be a landmark accomplishment. What was it like working with Dee Snider?

Tom:

He was fine. He was fine. You know, in the beginning, we did have a disagreement about which songs to do. He manufactured this story about him having to get down on his knees and beg to do “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” which I found a little bit like a nursery rhyme. I did not take the song that seriously. I don’t have the authority to tell them what songs we’re gonna do. I just don’t. The producer doesn’t. They hire me. You know, they’re paying me to help them. They could fire me. After we had decided which songs to do, the album went pretty well after we did the basic tracks. He was fine, and he approved the album and all the mixes. The minute that we finished the album, I was the worst person in the world. In [Dee’s] book, he said – I can’t quote it exactly, but he’s talking about an album that sold six million copies – and he said, “I think that Tom Werman single-handedly destroyed our album.” And I have to wonder about that statement. It doesn’t make too much sense to me.

Andrew:

How do you remember tracking Jay Jay French’s guitar parts for that record, Tom?

Tom:

That was tough. That was really tough. We did that at The Record Plant in New York, and then we went out to California to finish the record. They’re a New York band, and they wanted to do basic tracks in New York. So, we went there, and I just couldn’t dial in [Jay Jay’s] rhythm guitar sound. I just couldn’t. And we went through amp after amp, guitar after guitar, mic after mic, and on the morning of the third day, we finally got it. But it was the most difficult setup I’ve ever had. I would say that, generally, they were not too conversive with their instruments. Jay Jay was a forceful personality in the band. He’s a good guy, and he was always reasonable; they were all reasonable, and we all got along, and then Dee turned. My theory is that he worked for a long time with the band, it was his life – he worked for, like, seven years – and they finally got a hit, and it was with me, and I had a reputation at the time, and he was pissed about having to share the credit of that success with me. I think that was it because he never really specified anything else. He was beyond rude after that, and I emailed him twice to ask if he would have me on his little radio show so I could defend myself. Never heard from him, of course.

Andrew:

Is this a recent development?

Tom:

Oh, many, many, many years ago. Like fifteen years ago. Anyway, that was it. I let it go. I think the last time I really talked about it in an interview or a podcast, I said, “Listen, please just go and enjoy your privileged life. You’re welcome.” That’s the way I see it, you know?

Andrew:

You’ve produced a variety of dynamic personalities throughout your career. How did you manage the incessant conflict between George Lynch and Don Dokken during the recording of Tooth and Nail?

Tom:

Well, I didn’t do it very well. [Laughs]. I mean, I always got along with Don, and I loved George’s playing, and I really wanted to get the best out of him. He had done “Tooth and Nail,” the song, and I’ve always said that the lead break in that song was among the best I’ve ever heard. I mean, it’s phenomenal. He was doing another song -and he’s a major shredder, and he plays really fast, and he’s really good – but he was kind of noodling. And I said, “George, can you play something that actually goes from point A to point B, like ‘Tooth and Nail?’ Because that was a real composition, and it just seems to me like you’re playing fast and not going anywhere on this solo.” And he had kind of been twisted by the engineer, that bad engineer [Geoff Workman], who would single out one person in the band and keep working on him, saying, “You know, Werman doesn’t know anything. I’m doing everything. He’s terrible.” I mean, he did that, and he did it to other people he worked with. I didn’t know this, and [Workman] would actually make recordings in the control room. He would secretly put a mic up and record, and then he would take what I said and edit it so that it meant something else, and then he would play it for them. George heard it and thought it was real, and he pitched a fit when I told him that I wanted him to play something different. And I left because I had it at that point with the arguing between Don and George. I actually said, “George, I can see you’re really angry. Maybe you would feel better if you hit me. So, you wanna take the first shot?” And it’s a good thing he turned it down because he’s a tough guy. So, I left. I called their manager, and I said, “Listen, I don’t wanna finish this album.” And they got Michael Wagener to do it, and he did a fine job. He mixed the album.

Andrew:

What were some strategies utilized during the recording process to minimize flare-ups?

Tom:

Well, after you do the basic tracks, there’s no need for Don really to be there, ‘cause we didn’t do guitar in the afternoon and vocals at night. You could do it like a movie; you’d have one actor come in at a time to do certain scenes. So, I don’t remember exactly. There’s not much for me to recollect on that project because, first of all, it was unpleasant and I probably tried to wipe it out of my mind, and also because it was brief – I was only there for the recording part – and it was so long ago. I struggle to remember details. I know I managed it, and what probably helped was having Jeff Pilson there, because he was kind of a buffer and a peacemaker. He was one of the good guys.

Andrew:

How much of the album did you finish before you left the project?

Tom:

Pretty much the whole thing, in terms of recording. I didn’t mix anything.

Andrew:

How many producer points were you ultimately awarded for your work on Tooth and Nail?

Tom:

Probably two; half of what I was supposed to get. Maybe a little more, I don’t know.

Andrew:

Dokken was essentially on its last legs after Breaking the Chains failed to garner any traction, so what drew you to the band?

Tom:

Well, the same guy who was working for me, Tom Zutaut – who later went onto Geffen and great A&R success – he had signed Dokken and Mötley Crüe to Elektra. So, he wanted me to do both of them. I can’t remember which one came first, but that’s how I got together with Dokken. I really didn’t know anything about them. You know, when you start making records and you have some success, you tend to make records back-to-back and don’t have any time to listen to music or go to clubs. You’re just workin’ all the time. I spent twenty years in the control room. When you do a twelve-hour day listening to music, the last thing you wanna do when you go home at night is listen to music.

Andrew:

Being a Pennsylvania native, I am very interested in the time you spent working with Poison. You produced the band’s seismic Open Up and Say…Ahh! record, which I believe was the first and only album that you recorded digitally. What prompted that decision?

Tom:

Because I knew, having seen the band and rehearsed the band, that we would be doing a lot of punching in. Some of your readers may not know what punching in is; it’s just, you make a mistake, and wind the tape back and you play it again, then when you get to a certain point where the mistake is, you go into the record mode. The guitarist is playing along, and you fix it. He plays it correctly, and then at an appropriate spot, you get out of record mode. So, what you’ve done is, basically, you’ve corrected the mistake. It’s pretty seamless, because with digital, there was literally no gap between play and record, so it was seamless. With analog, which I used for every other record I ever did, you can do punching in and punching out successfully, but occasionally, you can hear where it goes in if you’re looking for it. If you’re just a casual listener, you probably won’t hear it. But it’s much more difficult to correct mistakes with analog. So, I knew I was gonna do a lot of punching because of the way these guys played. They were great guys, they worked hard, but C.C. [DeVille] was mercurial at best.

Andrew:

You say C.C. was “mercurial at best.” What were some of the challenges you encountered?

Tom:

You know, he was dabbling in drugs. I’m not even sure what kind, but I know he was probably doing something that involved a white powder. You know, he’d play something, we’d listen to it, and he’d say, “I’ll be right back.” Then he’d go to the bathroom, then he’d come back and say, “Eh, I don’t like it. Let’s start again.” So, that happened a lot. He was a good guy, he had a positive attitude, but what he was doing recreationally was very bad for decision-making and his playing. It took us hours and hours to do like a thirty-second solo. But you know, he played everything you hear – it just took a lot of takes.

Andrew:

How did Poison end up on your radar, as I understand they originally had another big-named producer in mind?

Tom:

Well, they wanted Paul Stanley to produce the record. He was unavailable and I don’t know if he ever produced anything else. But I was called into the Capitol Records office by Tom Walley, who was later A&R at Interscope and president at Warner Bros., and he said, “I think you could do a good job producing this band.” And we arranged a lunch and I sat next to C.C. – I remember sitting next to him – he was a major event. I mean, he was really a very entertaining guy. Anyway, we had lunch, we got along, we talked about the music, I guess, and then we decided to do it. I really enjoyed and remain very friendly with their manager at the time, Tom Molar. You know, we just got along, and we went in and did it, and everything was good. That was a very positive experience.

You know, Rikki Rockett, said, “I’m not the best drummer in the world. I know that. But I’ll work hard.” And he was exactly right. At one point, he had difficulty with a fill that he wanted to do; he just couldn’t get it. Bun E. Carlos was in town, from Cheap Trick, and I called him and asked him to come down and help, and he did. He came right down to the studio. They sat down, [Bun E.] worked with Rikki, and got him to do the lick. And that was very nice. Anyway, that’s the extent Rikki would go to get it right.

Andrew:

Hard work and showmanship are the hallmarks of Poison.

Tom:

They sound pretty good on the record we did, I think. I mean, there was only one ringer that I brought in, and only to do a couple of harmonica solos. Bret was a pretty good harmonica player, but he wasn’t really a great harmonica player. And so, I got a great harmonica player, who was actually in Willie Nelson’s band, strangely enough. He was good. On the album, you can hear some really good harmonica playing.

Andrew:

In light of the fact that some producers are keen on bringing in outside help, I was wondering what your take is on that.

Tom:

I only brought in three in all of the fifty-two albums that I did, and two of them were on Cheap Trick albums because I wanted a guitar performance that Rick wasn’t used to giving; not that he couldn’t give, necessarily, but it wasn’t his style at all. It was cleaner. In the case of “I Want You to Want Me,” the studio version, it was Jay Graydon, who was a jazz player. A real smooth guy. You know, it was a dance hall song – it had that dance hall 1930s feel to it when we did it in the studio – and I couldn’t get what I thought we needed out of Rick. Then an album or two later, on a cut called “Voices,” I got Steve Lukather, who is just a genius. He came in and played on “Voices,” and did a nice solo and nice fills. Then there was Mickey [Raphael] from Willie Nelson’s band, and that was it. I don’t think I used any other hired hands. I may have, but I honestly can’t remember. I didn’t do it much, and I never had anybody sit in for one of the band members permanently, like for the whole album, like they used to. There were people who were hired just to record, who never went on the road. They weren’t in the band – like a session drummer, there were a lot of those – and nobody ever knew about that until decades later.

You can have guests. A guest is great, but he’s credited on the album. That’s a plus. But a ringer, a hired hand, is something I wouldn’t do. If I had met with a band, auditioned a band, or had gone to see them live, and somebody in the band is so bad, or so incapable of playing his or her instrument that I had to replace them, I wouldn’t sign them. You had to be good for me to want to bring you to the label, or to produce. You had to be good enough.

Andrew:

What were the origins of “Every Rose Has Its Thorn?”

Tom:

Well, we were rehearsing in a facility in the San Fernando Valley. I had my acoustic guitar at rehearsals, and Bret said at one point, I think he had broken up with one of his girls – there were many – and he said, “I wrote a love song.” So, I gave him my guitar – he was a decent guitar player – and I said, “Let’s hear it.” So, he played “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” all the way through, strumming my guitar, and I said, “That’s a hit. That is a great song. We can do that song, and I think when we do it, you should play the acoustic guitar. You should play it just like you did right now, with that guitar, and then C.C. can do the lead stuff. But I want you to play the basic track.” And we did. That’s my guitar – which I still have – on the record. I really thought that was a country song, and I think it has been covered by one or two country artists, but it was the No. 1 lead cut immediately after I heard it. I have to admit or confess that I had, not a formula, but an approach to power ballads – and that was one of the great power ballads of all time. I say “power ballad” because it started off with a quiet acoustic and a quiet vocal, and then the whole band came in, and there was a big solo and a big crescendo, and then it faded away and ended with a quiet acoustic guitar. So, I had an approach to those. The power ballad was the way I got many of the bands I did to have hits.

Andrew:

You produced some of the most iconic power ballads of all time, from Mötley Crüe’s “Home Sweet Home,” to L.A. Guns’ “The Ballad of Jayne.” Was that something you were conscious of when you were recording records in the 80s?

Tom:

Yeah. Almost every hard rock band would have a ballad. I had an approach that I humorously called the “Kitchen Sink” approach to producing power ballads, which would start with almost nothing, and then eventually I’d introduce a keyboard string section, and maybe a Hammond B3, and some “oohs” and some “ahhs.” You know, I remember that when we did the backing vocals for “Every Rose,” somebody in the band, probably Bret, did say, “I don’t know. This could really ruin us, in terms of our credibility, with the ‘oohs’ and the ‘ahhs.’” But it didn’t seem to matter. At its fullest point, there’s a whole lot in that song; there are “oohs,” “ahhs,” keyboards, two guitars, and all kinds of stuff. And so, it worked, and certainly, the bands didn’t seem to mind.

Andrew:

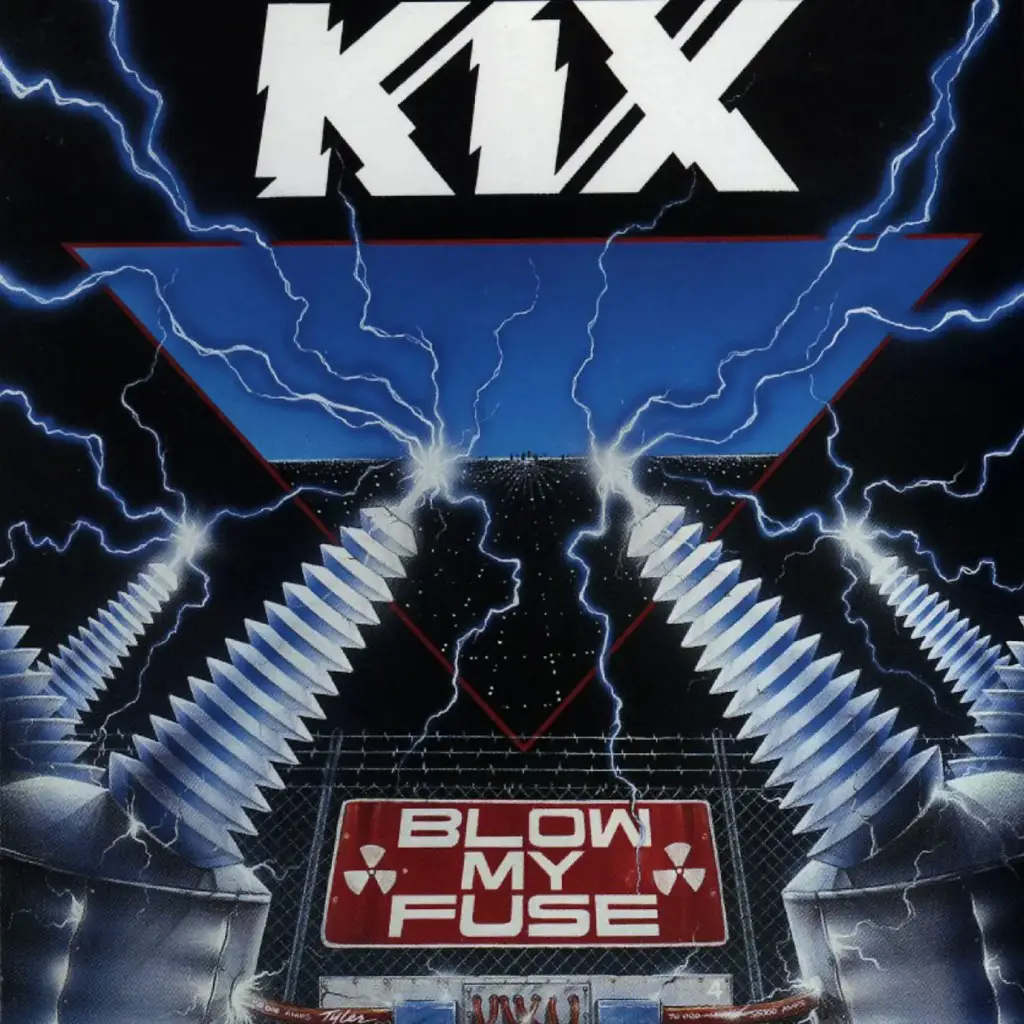

Being a huge fan of KIX, Blow My Fuse is one of my favorite albums of yours. How were you able to capture the band’s raw energy so perfectly?

Tom:

It wasn’t hard. We just recorded them; they knew what they were doing. The only difficulty was [bassist] Donnie Purnell, who was basically the dictator of the group, and also very distrustful of everyone around him. We didn’t have a good relationship at all. I got along really well with the rest of the band. It was kind of like Dee Snider and Twisted Sister, except that Donnie was really kind of surly in the studio, during the recording. He didn’t pretend that he liked me and then diss me later on as Dee did.

But Brian Forsythe was really great; he liked working, and he liked the way things were coming out. Everybody liked the way things were coming out. Then the second album, I think they brought in another producer – I cant remember his name – but we kind of co-produced and maybe split the songs between us, Duane [Baron] and John [Purdell], my engineer and a buddy of ours.

We definitely split up songs on the second album, because I remember I always paid a royalty to John and Duane. [Laughs]. We were a great trio, we got along really well, and we made some really good albums together – including [Girls, Girls, Girls], Poison, KIX, and L.A. Guns, too. We split that one. That’s when I was kind of getting weary of making records, I think, so I wanted to share the responsibility. And I got to pick the songs that I wanted to do, and that was great. I gave them the ones I didn’t like that much, or I thought would be problems.

Andrew:

KIX’s musical blueprint was largely ACϟDC, perhaps the band least likely to generate a power ballad, so how did “Don’t Close Your Eyes” come about?

Tom:

You know, I don’t know. I was glad that it was there, because it was commercial. When you say ACϟDC, I always thought they were uncomfortably close to ACϟDC. I mean, look at the electric theme; ac/dc is alternating direct current, and then there’s Blow My Fuse and Hotwire. Donnie Purnell was a huge ACϟDC fan, which is great, and so am I, but I think they were pretty similar in their sound. Which is why I liked them. They were a great band, but I guess that ACϟDC provided the music, and they didn’t necessarily come up with songs that were that different from ACϟDC.

Andrew:

Before we wrap things up, Tom, I wanted to ask you about Love/Hate, a band you championed and were instrumental in bringing to prominence.

Tom:

Well, yeah. It was tough for me. I wanted, at that point, to have my own production deals. So, I wanted them to sign with me, and I would bring them to a label and get them a label deal. So, the label would then pay my production company, and I would pay the band its share, and keep mine. That was what a lot of producers did. So, I brought them to CBS, and Ron Oberman was the head of A&R for the west coast at that time. I liked Ron, and he was a good guy, and lo and behold, he goes directly to them and signs them right from under my nose! I couldn’t believe it. And they gave them $800,000, I believe, and that basically destroyed the possibility of giving them any subsequent tour support. So, they had used up all the money on the signing, and artist development didn’t have a chance. I love the record, especially the song, “Why Do You Think They Call It Dope?” Fantastic performance. I don’t know, sometimes the stars don’t line up and the band doesn’t make it for one reason or another. And I think the label let them down.

Andrew:

Love/Hate was always one of the greatest mysteries to me, as they were ahead of their time, in my opinion.

Tom:

They could have been. They were not corporate rock; they were aggressive and a little bit alternative. Jizzy [Pearl] was good, but it was the bass player [Skid Rose] – he was a great bass player and a real hippie, kind of alternative guy – that was the sparkplug in the band. Anyway, I was really fond of that song, and I thought it would be the one, but they never caught on, really. They’re like a cult band. I had a few of those, like Mother’s Finest and The Producers. They were brilliant bands but never caught on for one reason or another. I blame the label for Mother’s Finest and The Producers; they just didn’t get it, and they didn’t work hard. That was Epic.

Andrew:

Now, how did Love/Hate initially land on your radar?

Tom:

Somebody, I think this friend of mine who was marginally in the music business, told me about them, and I went to see them at a rehearsal place. And I said, “Well, that’s it. I gotta sign the band.” And I was independent, so it was up to me to bring them to a label and get them a deal. When I played the music for Ron Oberman, he went around me and signed them, and I was pissed. I couldn’t believe he did that. I think, probably, if I had been able to shop them, it could have been properly done. They wouldn’t have given them this huge upfront advance. So, that’s the deal. I blame someone else.

Andrew:

How did you become one of the prominent producers in rock ‘n’ roll during those days?

Tom:

It wasn’t my choice. As I said earlier, I’m a pop guy. I always said I’d love to produce The Eagles; that’s my favorite music, really. I am not a metal guy. You know, I love string-fretted instruments and I thought they were among the greatest popular musicians that I ever heard. The A&R community, the people who actually put their bands and producers together for a recording project, wouldn’t let me do anything else. It was as if after Ted [Nugent], they said, “We’ll get Werman because this is what he does.” I did one very, very different album for A&M called Boy Meets Girl. I mean, totally different; beautiful love songs and lush arrangements. It’s a great album, and I loved doing it. We got along so well, and it was a beautiful project. They were songwriters who just decided to do an album; they wrote songs for Whitney [Houston]. That was what I wanted to do, basically. I was good at that.

I do like insistent, locomotive rock ‘n’ roll. I love ZZ Top. I love The Who. But look at Glyn Johns, who was kind of my role model. When I was much younger and starting out at CBS, he had done The Eagles’ first album, and then he did Who’s Next. I saw his name on the back of the album covers, and I said, “Jesus, who is this guy? I wanna be what he does. I wanna be a producer because he made a great record with this country-rock band, and he also made a great record with The Who.” So, anyway, I would have tried to do what he did, but the A&R people wouldn’t let me go there. They kept bringing me these metallic, hard projects, and so that’s why I kind of had to put a pop flavor into it.

Andrew:

As someone with such an extensive hard rock resume, the 90s were obviously a time of turmoil for that genre because the landscape was drastically changing. Did you find it challenging to navigate that period given your rock pedigree?

Tom:

Wow. Well, it wasn’t tough; it was great. It was great fun. I’m a pop guy, but they kept giving me these pretty hard-edged bands – not metal, but hard rock – and I didn’t particularly want to do any more of that. I’m much better at The Eagles and that kind of music. Give me some fretted instruments, and maybe a little acoustic, and a lot of harmonies, and I’m happy. I just happened to get in there, and I was lucky in terms of timing, because look at all the hard rock bands from the west coast in the late 70s and the early and mid-80s, it was huge, The Sunset Strip thing. It was good timing for me, but when Nevermind came out, that was it. I was finished. And I could tell immediately because none of the Seattle bands would work with me, and I don’t blame them; my association was with corporate rock. For Soundgarden or Pearl Jam to work with a producer who had worked with Twisted Sister or Mötley Crüe, it wouldn’t have worked for them. It might’ve worked musically, but in terms of street credibility? No.

Andrew:

Last one, Tom. At what point did you say, “I’m done,” and decide to move on to the next phase and what have you been doing since then?

Tom:

Well, in the mid-90s, I was doing stuff like Pariah, Hash, and Lita Ford. Stuff that was good, but people just weren’t buying the kind of music that they were in the late 80s, and I kind of saw the writing on the wall. As my projects got less and less high profile, I said, “Well, at some point I’m gonna do something else.” And I had done like fifty albums by the time the late 90s rolled around, and I was burnt. I was burned out, and I thought, “It doesn’t make too much sense for someone in his early fifties to be making records for sixteen-year-olds.” So, I did a movie [Rockstar], a great movie that unfortunately came out a week before 9/11, and then we moved here. I said, “Well, that’s it. I’m pretty much finished.” I didn’t have any projects, and I took a job at Capitol Records, in a new division of theirs that didn’t last. I had a two-year contract, and EMI closed the company after nine months, and they paid us off.

So, I played golf for a while, and I complained, and then my friend Tom Kelly – who wrote “Like A Virgin,” by the way – we were playing golf one day, and he gave me a book. He said, “You need to read a book. I’ll give it to you.” It was a book about unanticipated change and how to deal with it; it was called Who Moved My Cheese? It’s a well-known book that corporations use. I read it in forty minutes; it’s very quick. It’s like a kid’s story about two mice in a maze and it’s got a moral to it. And I said, “What am I doing? I gotta reinvent myself. I can’t sit around here and be angry.” So, two weeks after I finished the book, I was here. I was in the Berkshires, and I was looking for a bed and breakfast; a place to renovate and turn into what I thought it was time for: a luxury bed and breakfast. Because bed and breakfasts were typically extremely basic; you were lucky to have a radio in your room.

So, we bought this old place, we renovated it for eight months – I made it all suites – and we opened on July 4th weekend of 2001. Our first guest was Linda Ronstadt. She was playing at Tanglewood down the road, and I knew her old producer and manager, John Boylan, and I called him up and I said, “Why don’t you all stay here? We’re seven-tenths of a mile from Tanglewood.” So, she came, and we built the business over – it took about five years to really start making money – which I didn’t have in mind. I just wanted to pay the mortgage and live in the country, and it was great. It’s bliss here; we’ll never leave. We just sold it after twenty-one years, and we moved up the street. We actually live about three-quarters of a mile away from Stonover Farm. And Stonover Farm, that’s what it was called, we were award-winning; we won two awards. We had some really famous people stay there, and we had a fabulous business, and we were voted the No. 1 spot in Massachusetts to have a barn wedding. We had a fabulous business, but just like the record business, at twenty-one years, it’s enough.

I’m very late to retire; I’m kind of a workaholic. All my friends retired ten years ago, and I’ve been retired now for five months. I’m waiting to move into our house, which is being renovated. It’s been tough, because of the supply chain and labor thing. We’ve owned the house for a year-and-a-half, and we’re gonna move in in a month. So, that’s the deal. That’s where I am in life. I finished a book, we’re gonna start taking it to agents very soon. I’m pretty sure it’ll be published. It’s different from all the other books on rock ‘n’ roll in the 70s and 80s; it’s pretty instructional, it’s educational, and it’s fun. So, that’s it. That’s where I am.

Andrew:

This book will be a must-read for me. I’m very much looking forward to its release.

Tom:

Yeah. I enjoyed writing it – it’s taken three years – but I really think it’s a great book. I’ve sent chapters to a lot of people, and I get very positive feedback. So, I think there’s a big audience out there for a retrospective of how the industry worked, how we discovered talent, developed it, recorded it, monetized it, promoted it, and put it on the road. A lot of people don’t know about that, or how we made records back then; warts and all. It’s all about how it was done. Then, there are lots of parts about people that I had experiences with, like [Bruce] Springsteen, George Harrison, and [John] Belushi. Things people don’t know. It was only me and them.

Be sure to check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/