All images courtesy of Tony Currenti/Peter Clack

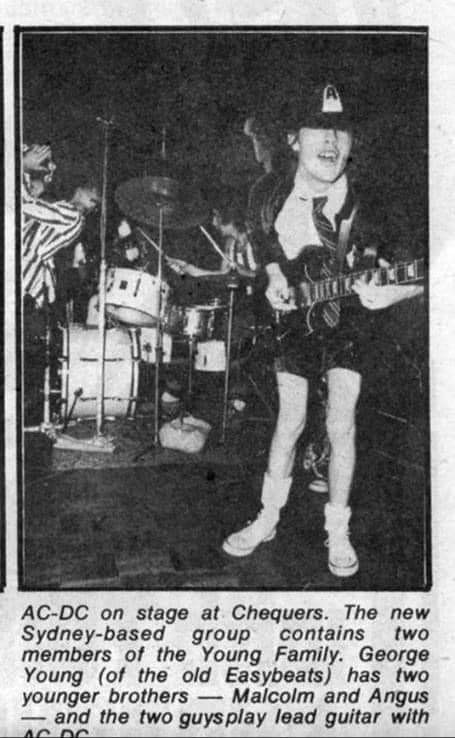

ACϟDC’s humble origins accurately foreshadowed a long way to the top for brothers Malcolm and Angus Young, who spent the band’s early years experimenting with sound and style, while often accompanied by an ever-changing lineup of musicians as they navigated through the initial stages.

Obscure and relatively nameless, these contributing members mired in anonymity throughout their respective tenures and have since become mere footnotes in the annals of rock ‘n’ roll history, though they will forever carry foundational ties to the legendary Australian rock act.

A majority of the ancillary members, such as original vocalist Dave Evans, bassists Larry Van Kriedt, Neil Smith, and Rob Bailey, and drummers Colin Burgess, Ron Carpenter, Russell Coleman, Noel Taylor, and Peter Clack, never stayed long enough to achieve relevance, much less record a studio album with ACϟDC.

However, Clack and Australian-based session drummer, Tony Currenti, bear the distinction of being among the least documented figures in ACϟDC lore, given their respective timelines and contributions.

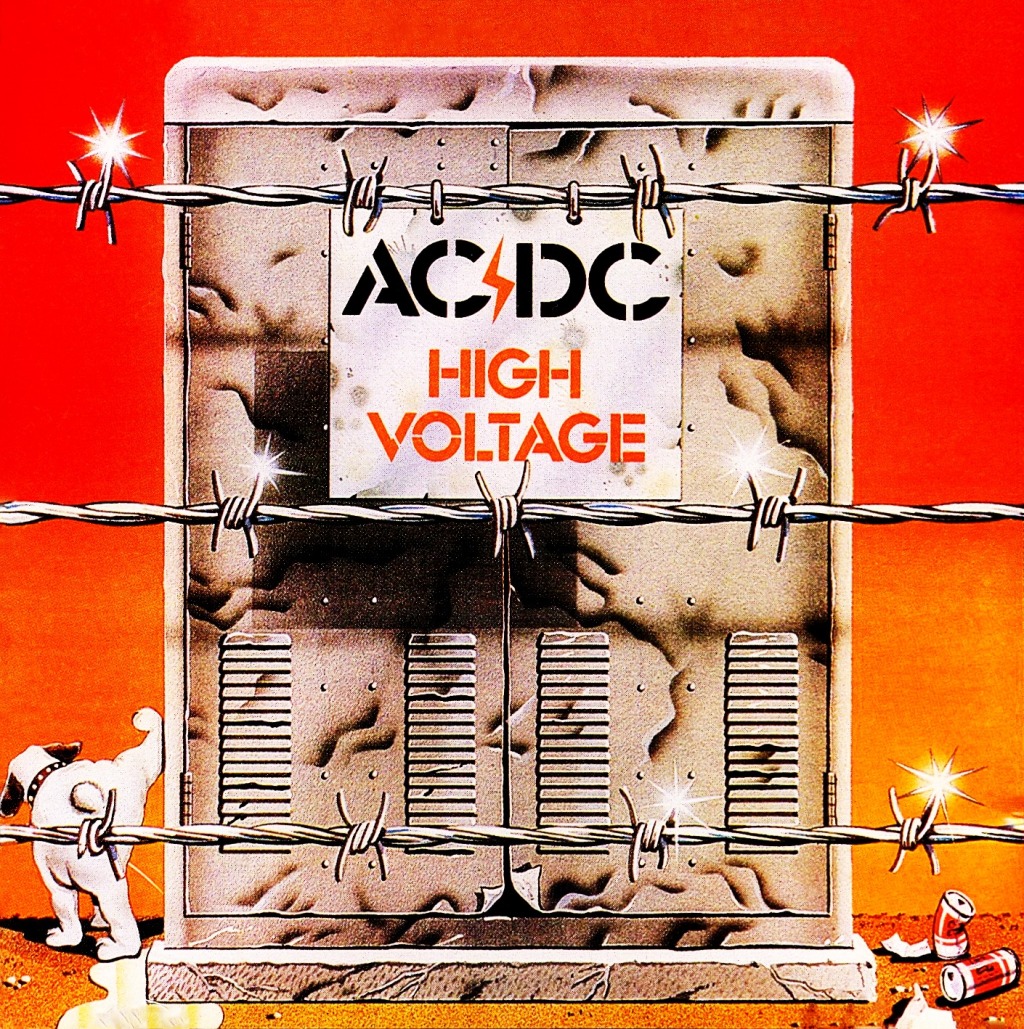

Clack became the band’s fifth drummer in April 1974, replacing Taylor behind the drum kit. Clack’s stint lasted all of nine months, but he managed to lay down the drum track to “Baby Please Don’t Go” on the Australia-only version of High Voltage in 1975, a song that also appeared on ’74 Jailbreak (1984).

The recording demands of High Voltage led to Clack’s replacement after early challenges.

“I mean, maybe if I had a day’s rest or something like that, I could probably do a better job,” Clack reflected. “It was like one in the morning after playing, so it was a pretty demanding process.”

Clack was also present for some of the most defining moments in rock ‘n’ roll, perhaps none more pivotal than the inclusion of the late Bon Scott.

But despite the band’s mountainous climb to prominence, and subsequent worldwide appeal, Clack doesn’t regret squandering his chance to ride along on the rock ‘n’ roll train.

“I’ve just passed it by, because I’ve had so much more to do — and more enjoyable things — like being in a Big Band for twenty years,” Clack remarked.

“And I’m still playing now and recording, but it’s a bit slowed down due to the COVID affair up here. I’ve had some really good bands, jazz, and stuff like that, which has been good. But I don’t have the income that those guys would have developed. But then, I wasn’t around when they left and got into that scene, you know? So, I just took off from where I left, and that was it. It’s another chapter of my playing.”

With Clack on the outs, George Young — the older brother of Malcolm and Angus and co-producer of High Voltage — enlisted the services of Currenti, drummer for Jackie Christian & Flight and renowned session player, to finish the album. Currenti, who was already recording the last single with Jackie Christian & Flight, “Love Fever,” at Alberts Studios, obliged, playing on the remaining seven tracks with flawless execution. Three of Currenti’s tracks, “You Ain’t Got a Hold on Me,” “Show Business,” and “Soul Stripper,” also appeared on ’74 Jailbreak.

I recently had the privilege of conducting sit-downs with Clack and Currenti, who were both incredibly gracious with their time, and provided unique insight and perspective from their respective tenures.

Peter Clack (1974-1975)

Andrew:

Peter, you eventually moved to Sydney and landed with a band called Flake, which featured future ACϟDC bassist, Rob Bailey. What do you remember about the band, and what subsequently led to your opportunity with ACϟDC?

Peter:

Well, I finished college and I was in a country town called Ballarat. And I thought, “Well, okay, they’re seeking Melbourne, I think I’ll go to Sydney and seek a fortune.”

I had a few friends up there; I lived in Paddington, a pretty central area, you know? I watched the Sydney newspaper and I checked out a few bands who had advertised and asked for a drummer. I go along, check it out … maybe yes, maybe no … and then I finally got on with this band and they had called themselves Flake. The bass player was from Perth — I think they all were, actually, if I remember. So, I started playing with them. We got into a place called Chequers, an old cabaret place in Sydney. We had a residency there. You’d play for a half an hour on, a half an hour off … a half an hour on, a half an hour off, from, if I remember, about nine until 3 am. This guy [Ray Arnold], who used to be a roadie I was told, came up one night and he offered the bass player and me a phone number, so we took it. He said, “Yeah, we’re looking for a rhythm section.” So, I rang up, and sure enough, there’s this address in Sydney. And we came in and knock, knock on the big iron door — like what you see in Beverly Hills — and there’s George Young from The Easybeats. We had a bit of a play, and everything was cool. They were all satisfied; it was great. So, that was it. And we were told we were in ACϟDC.

On Ray Arnold: “He knew everybody who was anybody in Sydney in those days, about 1973ish. But we got to know him; he’d always be at Chequers. And of course, that place was packed every Friday and Saturday.”

Andrew:

Was there a conventional audition process?

Peter:

It was just like having a bit of a jam with some guys, nothing more. There weren’t any formalities about it. Angus and Malcolm were cool, calm, and collected, being brothers. And I suppose the feel and the groove were something that was harmonious.

Andrew:

Were you already aware of Angus’ status as an ascending guitarist upon joining the band?

Peter:

I’d never heard a thing about him. Nothing. Because that was the start — we were playing at all the suburbs of Sydney — Panania down to Canoelands, pubs, and hotel dances, and all that sort of stuff back in those days. That was back in like 1973; things were different then. It was all new — that was the beginning — like eight gigs a week. After a while, the road does tend to burn you out.

Andrew:

What did the ACϟDC get-up consist of in those days?

Peter:

Well, it was glamour rock. There was Bryan Ferry and David Bowie in those days, and we were all dressed up in shiny satin and stuff like that.

Andrew:

You and Rob Bailey obviously played together in Flake before joining ACϟDC, where you comprised the rhythm section for a short time. Talk about your chemistry with Rob.

Peter:

I think it was just, we didn’t overplay, we just listened to each other. It’s not always what you play, but what you don’t play — which is a classic line that a lot of people don’t know. And we seemed to sit in with the feel, and the push, and the groove quite well together. And he was a nice guy, and we had a good time.

Andrew:

How would you describe your drumming style in those days?

Peter:

Well, in those days, after doing a lot of jazz in style and listening to a lot of different sorts of bands before glamour rock — which is what ACϟDC was — I suppose just basic rock ‘n’ roll.

Andrew:

Your previous Jazz background was a vast contrast to what was asked of you in ACϟDC. Did you ever find yourself struggling to keep tempo?

Peter:

I suppose I was used to it. Doing it all the time, your body adjusts. The first teacher in the country town, he said, “The tempo has to be maintained. Do the best you can no matter what happens. The show must go on.” Now, I might add, that “Baby Please Don’t Go,” I did the first single, “Can I Sit Next To You, Girl” and I also recorded “Baby Please Don’t Go.” And that was full-on; that was a full-on song. Flat to the boards, you know? That was also put onto ACϟDC: Family Jewels — that album — and No. 1 was “Baby Please Don’t Go.”

Andrew:

What is your recollection of how Bon Scott joined ACϟDC?

Peter:

We played at Larg’s Pier in Adelaide, and Malcolm, rest in peace, just said, “Look, see those guys at the backend? That’s Fraternity. They must have just got back from London.” Malcolm knew Bon, and so, they had a bit of a chat. And I think they communicated again the following day. Malcolm had a bit of a private meeting and just said, “What do you think about Bon singing?” And I said, “Sure, whatever.” It’s like, “You’re the boss,” which he was. And then it seemed to take off. But then Bon said, “No. No way. No chance. I’m coming back here with my wife, who I promised, and I’m gonna get a job and I’m gonna stay here in Adelaide. No more on-the-road. Nothing. That’s it.”

And then about a week later, Bon got back to Malcolm, and he said, “Look, it was about six o’clock in the morning, I was walking along the beach in Adelaide, and it was freezing cold. I got this job…” Malcolm said, “What’s the job?” And [Bon] said, “It’s painting a boat.” He was walking along this dirty, big, rusty merchant … a great big ship. It was all rusty and dirty; it was just impossible. Bon said, “Shit, I’m not gonna paint that!” And he turned around, came home, and he said, “Okay, I’ll join.”

Ah, but he didn’t actually link up until we got back to Melbourne after our tour. And that’s when we started playing Hard Rock Café, in the central business district, run by Michael Browning. And that was in the city, but we had to get together and do some rehearsals, but we were in a house.

Andrew:

Any recollection of Bon’s first gig?

Peter:

I think it was at a park in Sydney, outdoors on a Sunday afternoon. A big show. I don’t remember the name of the park. It was probably only about 2,000 people there. It would have been a few other bands on, too.

Andrew:

What was the band dynamic like with that lineup of Bon, Malcolm, Angus, Rob Bailey, and yourself?

Peter:

Well, it was just pure adrenaline before we even started playing. Just get up on stage and the scene was in the body language. We played in a place over in Adelaide called Countdown. That night was just incredible. Like Angus, he just flew off the rails. Just insane. I went to see him after — I had come back after their first tour overseas at the Rod Laver Tennis Stadium in Melbourne — and I had come backstage to visit with my wife and daughter. Every layer of warming up, there was a bottle of oxygen for Angus ‘cause he used to burn the energy, too. Everybody else sort of hung together; we could all hear what was going on. Malcolm was brilliant all the time as a rhythm player and a singer, Rob Bailey, and Angus. It was just dynamite.

Andrew:

Is there a particular gig that vividly stands out from your tenure?

Peter:

We were on the Lou Reed Tour, off the Transformer LP; we were his support band on a national tour. We played at this hotel in Adelaide in between the main Lou Reed shows, and we were doing the song called “Baby Please Don’t Go.” There were these thugs that were just hanging around the front of the stage — and the stage was only about a yard high — and Angus started revving up the guitar. It’s sort of got this part — there’s this theme in it — and then it takes off. It’s like the ensemble kicks in. And [Angus] came and booted this asshole right in the chops as he was at the very start of the peak of his solo. That was a classic, but we had a police escort out.

Andrew:

The recording of ACϟDC’s debut album, High Voltage, required efficiency and precision due to time constraints. What are your memories from the recording process?

Peter:

Well, it had to be done in a week and it had to be done at one o’clock in the morning. So, the only track that I got down was “Baby Please Don’t Go.” The others were all done by a backup player that George knew because I had been playing every night and I just didn’t have the — I don’t know — the stability or the constant reproduction. And [George] came up to me and he said, “Look, you’re obviously pretty stuffed. But do you mind if we have someone else fill in and I’ll try someone else on some of the songs?” I said, “No, no, no. Not at all.” That sort of didn’t work out too well for me.

Andrew:

Stuffed?

Peter:

Well, yeah, after playing through the songs. They weren’t up to the intricate standard of perfection when you’re recording.

Andrew:

Drumming in ACϟDC proved to be a volatile gig in the early days, with Colin Burgess and Noel Taylor among the handful of players that cycled through before your arrival. Did you ever find yourself looking over your shoulder, so to speak, or feel intense pressure to deliver?

Peter:

No, I didn’t, really, ‘cause I hadn’t experienced any of that at all. I just joined the band, kept playing, everything was cool. One track I did play on, their first single, was a No. 1 in Perth. Considering the business side of things, and I suppose that works both ways, it didn’t work out. But then again, when I said the business side of it, Rob Bailey — well, that’s a little bit different to recordings — but there’s some business that went on there, and Rob Bailey left the band. However, I didn’t because I kept going — no apparent reason — and George Young filled in on bass. That was really good, but then the novelty wore off. I was living out of a suitcase after six months and just going bull-bang, bull-bang, bull-bang; that style. I thought I could do better. I got more adrenaline out of playing in the [Allan Hessey] Big Band for twenty years than I did ACϟDC for a year if you know what I mean because they weren’t big in those days. And the money wasn’t there.

Andrew:

Were you ever compensated for your contributions?

Peter:

No. Rob Bailey and I, when we got back from No. 1 in Perth, we went to Alberts, and we went upstairs to see the boss, Ted. He said, “Look, I got a pie chart here. Have a look, fellas.” And then we looked at royalties and we saw … Sixteen percent: Young, Young, Scott; Young, Young, Scott; Young, Young, Scott — this is off High Voltage — Young, Young, Scott; Young, Young, Scott; Young, Young, Scott. They had sixteen percent royalties; Rob Bailey and I: One cent. We’d been working right from the dirty start; we’d done all the dirty work and everything like that, including all the concerts, and encores, and all of that sort of thing. But maybe my style just didn’t suit — I don’t know — but I didn’t challenge anything ‘cause I didn’t realize the band was gonna be so big. But I’ve just swallowed that. It’s really only the “High Voltage” and the “Baby Please Don’t Go.” But I never got any gratitude for those, although they did put it on High Voltage as well as Best Of [Family Jewels]. The only song from High Voltage that got onto [ACϟDC] Family Jewels, was what I was recorded on, which was “Baby Please Don’t Go.” Now, that was available on video, and it’s got Phil Rudd miming, but that’s me playing behind because that’s me hitting cymbals when he isn’t, and he isn’t doing what I used to do on the snare drum and all that sort of stuff.

Andrew:

What was your first move following your split from ACϟDC?

Peter:

I went to the Gold Coast and had a couple of months’ holiday on the beach. I went back to Ballarat, where I grew up; had a bit of a holiday, went back there to see some friends. Then went to Sydney and started playing again.

Andrew:

So, how soon until you resurfaced in another band, and what were some of your endeavors thereafter?

Peter:

I had a few offers, you know, but I didn’t take ‘em on. I just wanted to chill out a bit after all the noise and all the action, full-on. I just took it easy. I didn’t play probably for about a year or so, at least, just to get it out of my system. Then that’s when I started playing a bit more Rock ‘N’ Roll. Went up to the Northern Territory, made a lot of money with a band up there. Then from up there, I had an invitation to the Percussion Institute of Technology on the West Coast. I passed all the tickets; I just didn’t have $15,000 for insurance in case I broke an arm, so America could put me on a jet and fly me back here! Anyway, I got onto Graham Morgan in Melbourne from meeting a guy at the casino up in Darwin; I was playing there, and he was playing in a theatre up there. And I knew the guy, roughly, from down in Melbourne. He said, “Look, the guy’s just finished up a contract that he’s been on. I’ll give him a call.” And he rang him up and he said, “Sure.” So, I resigned from the band I was in up there and went straight back to Graham Morgan. And that was when things started to happen; playing real music, I just got right into that sort of music and kept going. So, it was really good.

Andrew:

And you also spent some time with the Melbourne-based band, Raw Sylke?

Peter:

That was a guitarist, drums, and singer. We did a lot of recording. We got a lot of radio play, it’s called Underground Release, or something like that, and we got played on that quite a bit. I finished with that band about ten years ago; that’s when I went to Brisbane.

Andrew:

Unlike some musicians who separate themselves from the industry altogether, you never stopped playing, and are now sharing your passion and knowledge with others as a drum teacher. Tell us more about that.

Peter:

Before I left, I sent all these references I had from teaching at Mary Immaculate, a lady’s college in Fitzroy, and another high school out in Dandenong. I sent all those references up to the education department up here — like I’d played in the Sydney Opera House when George Young and Stevie Wright released the recording of “Evie” by Stevie Wright — and we were there to put that inside the opera house. I had lots of references, very good ones, especially from my teacher of five years, Graham Morgan. And they said, “What do you mean? You can’t call drums an instrument! It’s not a musical instrument!” So, I had to do this sort of — I don’t know what it would have been — a degree or something like that with a piano, guitar, timpani, xylophone, something that’s musical; not a drum kit. I thought, “Well, fuck you. That’s just outrageous.” I couldn’t believe that. After Jesus Christ Superstar, that is a tall order; the detail, time signatures, the changing, and all that sort of stuff. New York Dolls; Coco Cabana. I thought, “Ah, shit. Stuff this. I’ll teach privately. I’m not gonna go to Queensland with an attitude like this.” So, I’ve just been taking on private people. I’m a registered teacher up here, but I don’t have the qualifications to teach in a public school. I could teach in a private school or an independent school up here — I’m registered to do that — but nobody who teaches drums up here, in those two types of schools, would want that. They wouldn’t wanna lose their job, or they wanna keep the job that they’re doing — like playing guitar and teaching some girl or guy how to hit a drum with a drumstick. So, I just do it privately.

Andrew:

I really appreciate you taking some time to talk with me about all this, Peter. Before we go, tell us what’s next on the docket.

Peter:

Well, I recorded three tracks for a guy I know — a guitarist — and he sent me a copy of one. It’s not mixed yet, but it’s really, really good. Also, the trio I’m playing with, I’m hoping that when COVID is controlled — I don’t know what the outcome is gonna be from that because musicians attract people — anyway, the trio, one day we might even get on stage and get paid for it. But at the moment, the guy I recorded those three songs for, he’s got another ten that he wants me to play on. So, I’ll just hang in here and carry on.

Tony Currenti (1974-1975)

Andrew:

Tony, you migrated from Sicily, Italy to Sydney, Australia as a teenager. What do you recall from your early beginnings in Sydney?

Tony:

I came here as a 16-year-old in 1967 with my parents. My father never bought me a set of drums for me to play on, so I was pretending to play drums on my mother’s kitchen chairs. As soon as I arrived in Australia, the first thing I did was buy myself a set of drums. While I was walking in Newtown, I heard this band rehearsing, and I went in and became their drummer for a little while until we formed a new band called The Inheritance. That’s how it all started.

Andrew:

While with Inheritance, the band landed a residency at a place called The Groove Room. Talk about what it meant to have a residency in those days.

Tony:

That was a big job. Seven days and seven nights a week. We didn’t have enough songs to do the gig, but we rehearsed every break the next day. We worked from midnight ‘til three in the afternoon, and then six to midnight. So, while we were having our break, we were rehearsing songs to go through the nights. I found it very demanding, and I actually learned a lot by rehearsing every day and playing every day.

Andrew:

The Inheritance subsequently morphed into the Jackie Christian Band, but what incited the pivot?

Tony:

We had two singles out; they both flopped. So, we thought that changing our name would have brought us better luck. [Laughs].

Andrew:

Did it ultimately end up giving the band a boost?

Tony:

It did work a little bit, but not that much. Effectively, it was the same band. The only difference was that we got the attention of [Harry] Vanda and [George] Young. They liked the band, they wrote songs for us, and we recorded two of the songs under Jackie Christian & Flight. So, it did work relatively OK.

Andrew:

Speaking of Vanda and Young, do you remember your first meeting?

Tony:

Well, our first meeting was if we were interested to record some of their songs, and them producing the band. So, we thought we were gonna be a big hit, because Vanda and Young were very well known, and they had a great reputation. We sort of thought they were gonna make us a big band.

Andrew:

The Jackie Christian Band undergoes further modification and is rebranded as Jackie Christian & Flight shortly after. What influenced the name change?

Tony:

Well, Jackie Christian recorded a single as a solo artist with EMI, and he needed the band to back him up and we came up with a band name. In the end, we came up with ‘Flight’. It was pretty much the record company wanting a fresh face that influenced Jackie Christian to change his name to that.

Andrew:

As your relationship with Vanda and Young blossomed, what was some of the feedback that George gave you regarding your playing?

Tony:

Well, in ’73, coming back from England, they didn’t know the band at all. They heard us performing in pubs and residency and they liked the band, and they approached us to record one of their songs. I think George liked my drumming because I was a simple drummer that got the job done without too much fuss. He often said to me, “If you can keep timing for four minutes, you’re my kind of drummer.” So, that stuck in my head ever since. I kept things very simple.

Andrew:

Your relationship with Bon Scott predated your stint with ACϟDC. Do you have a Bon story or memory that you care to share?

Tony:

Well, I met Bon Scott in ’68 when he was with The Valentines. But my English was very poor, and every time I opened my mouth, he cracked up laughing because he thought it was funny. That’s my recollection of Bon that I remember quite clearly. Every time I tried to say something, he cracked up laughing and I couldn’t understand why. Finally, he told me, “When you try to speak English, it comes out in a funny sort of way.” So, that’s stuck into my head.

Then the next time I saw him, we actually shared the gig we were doing at Jonathan’s Disco, with Fraternity. And [Bon] was the singer of Fraternity. We were there for a couple of weeks. Then [also] seeing me in concerts and other places, so I got to know him a little bit. But I only knew him as a member of another band. We never shared accommodations and we never really went out. We always stuck at the bar with Johnny Walker, that was it. So, I don’t have any personal recollection — what he was like — the only thing that I know is that he was a fun person to be around. I enjoyed his company, he was always happy, nothing bothered him, and he was always good for a laugh.

Andrew:

Bon’s band, Fraternity, was quite successful in the early 1970s. Coming up through the scene at the same time, what were they like?

Tony:

They were a great band. They were the No. 1 band in Australia in the early 70s. We actually got their gig — they went to England for six months — and we took over for them at Jonathan’s for the full six months. But when they came back, instead of sacking us, they kept us for two weeks working with them. We were a young band coming along really well, that’s why George and Harry liked the band so much. We were a fresh rock band that most people liked.

Andrew:

How did you end up becoming affiliated with ACϟDC, Tony?

Tony:

It was very simple. I was recording the last single with Jackie Christian & Flight, a song that Ray Burgess ended up singing and made a hit out of it … “Love Fever.” We recorded it as Flight, but George did not like Jackie Christian’s singing on that song. So, we tried with the rhythm guitarist singing it, and they didn’t like that either, so they ended up giving it to Ray Burgess. And that particular night that I finished recording the single, George approaches me and says, “Can you hang around until midnight? My younger brothers are coming to the studio. They would like to record some songs with you.” I accepted it and waited for them to come. The first person coming up was Bon because he remembered me, and he couldn’t wait to see me. That’s how it started. I got asked to stay back in the studio — we finished at 11:00 — and midnight was Angus and Malcolm with ACϟDC coming up to the studio.

Andrew:

So, was the drummer you were replacing, Peter Clack, still there, or had he been sacked already?

Tony:

No. Well, only they know exactly what happened, but Peter Clack wasn’t present at all. I think George asked his brothers to come along without him because they had another drummer trying out for the album. So, I never really met Peter Clack. I only know that they already recorded “Baby Please Don’t Go,” and George wasn’t very happy with the time that it took to record it. They spent a lot of time on that song, and he just wanted somebody to do the job a lot quicker.

Andrew:

Did the brothers ever indicate what kind of sound they were looking to capture, and what was it about your skill set that they were drawn to?

Tony:

It wasn’t so much ACϟDC, it was very much George and Harry. With Jackie Christian & Flight, I was a lot more involved, and I was playing in a different style. Recording stuff on High Voltage and Black Eyed Bruiser was a lot more involved in it, and George appreciated that as well. But what they liked, was the direct impact that I had on their songs. It was pretty much playing to the band and not to myself. Anytime George needed somebody to record something, he used to always call me — until ’76 — when I disappeared from the scene. I don’t know, after that, what happened, because I officially retired and never played again for nearly 40 years.

Andrew:

What are your memories from the recording of High Voltage?

Tony:

“High Voltage” was the very last song we recorded. The first two songs we recorded the first night were “Show Business” and “Little Lover.” “Show Business” got done in half an hour, then we spent quite a bit of time having coffee and tea and a chat. Then we did “Little Lover” and finished it that night. They were very happy and said, “Well, the way we’re going, we’re gonna do the album in a week!” So, they were very happy about it. It was nothing difficult for me to do; I just kept it simple, and it happened to be what they really wanted.

Andrew:

Perhaps you can clear something up for me that I’ve always wondered–was it Rob Bailey or George who played bass on the album?

Tony:

Well, I recorded mostly all songs with Rob Bailey. The only songs that George had an input in, as far I remember, were three songs out of the eight — “Stick Around,” “Love Song,” and “High Voltage.” I had the pleasure to play with George, Angus, and Malcolm at the same time, and I’m gonna cherish that always. But Rob Bailey did the rest. [Rob] thinks he’s done it all, and he probably did, but the actual bass playing on those three songs are different if you listen to them, and that’s George. Whether they did it after or … I don’t know. But I remember playing with George — especially on “High Voltage.”

Andrew:

The versatility and execution of session musicians aren’t taken into account nearly enough. Could you shed some light on what that responsibility entails?

Tony:

At that particular moment that I recorded the High Voltage album, I was more interested in how the single “Love Fever” was gonna do for Jackie Christian & Flight. I never really thought about it, you know? Being asked by George, for me, was a big thing because I followed the Easybeats for many years, since the late 60s. And having the pleasure to play with two members of the Easybeats, and producers as well, for me, was a highlight. On Black Eyed Bruiser, I recorded with George, Harry, and Stevie Wright, which is most of the band. So, it was an honor for me to be involved with them.

ACϟDC was a young band, which they had a new singer in Bon Scott for four weeks when I recorded with them. I never met Dave Evans until very late, in the last four or five years. So, I never knew Dave Evans at all. It was a new band, a new ACϟDC, that was getting good tracks down on High Voltage. And that really made ACϟDC, even though they had a single “Can I Sit Next To You, Girl” with David Evans.

I never knew Dave. I met him, actually, in Sicily. We worked together with a tribute band. That was very nice. I quite enjoyed that.

Andrew:

You may not be of the same opinion, Tony, but nearly 50 years ago, it was you who essentially laid the foundation for drumming in ACϟDC. What does that significance mean to you?

Tony:

Well, I gotta give a lot of credit to George, because he never told me how to play or what he expected of me. He just said, “Keep it simple,” and let me do what I wanted to do. So, what you hear in High Voltage is actually me without any influence of anybody else. ACϟDC songs are pretty straightforward, so there was not much you can add to it, you just gotta be there. I didn’t find it very difficult at all. We did the eight tracks in four nights, after midnight. I’m very proud to have been the one that George chose to do it with.

Andrew:

Following the completion of High Voltage, were there ever any preliminary talks of joining the band as a permanent member?

Tony:

Well, they asked me twice while I was recording. The first time was George. I said, “Look, we just recorded a single for my other band. I’d like to see this through.” So, I said, “No.” A couple of nights later, after most of the tracks were done … we recorded “Soul Stripper,” “She’s Got Balls,” “Stick Around,” and “Love Song” … the three brothers actually come to me and ask me again. I said, “Look, it’s very difficult for me to make a decision right now.” And then Angus mentioned, “We want to finish the album as soon as possible because we’re gonna go to England very shortly.” And when he mentioned overseas, it sort of clicked — I had an Italian passport. I could not travel overseas. So, that put an end to everything.

I could have said, “Yes.” I could have joined the band, record another couple of hard ones with them, and then when it was time for them to go overseas, I couldn’t go. I didn’t know how much time I had, so it was actually better for the band that I said, “No.” They had a good chance to find a good drummer, which Phil Rudd is. I was very happy with the choice that they made with Phil Rudd. He adapted to my style very quickly, and I suppose George was happy with him as well. I don’t know; after that, I sort of moved away from music altogether. So, I don’t know.

Andrew:

Were there ever any regrets over the decision?

Tony:

It was my decision entirely. I think I did ‘em a favor by saying, “No.” Because if they would have said to me, “Listen, we’ve got 12 months. Get a citizenship in those 12 months,” I would have probably done it. But they didn’t give me that choice. They wanted to go overseas pretty much straight away. I couldn’t say, “Yes,” because that would have been underdone like that. No, I’ve got no regrets at all.

Andrew:

By the late 1970s, you decided to walk away from music and embark on another endeavor entirely. What influenced your decision?

Tony:

I walked away because music in itself wasn’t going to give me a future, at that particular moment. I had a chance with ACϟDC, and I blew it. I had a chance with Stevie Wright’s All-Star Band, and Stevie Wright blew it. [Laughs]. So, I sort of was in limbo for a little while, and I didn’t know what the future held for me. I had a go in other bands like the 69ers; I was with them for a little while. And then a little band called Winter, but it wasn’t going anywhere, so I decided to get married, open up a pizza shop, and call it quits.

Andrew:

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about your shop, Tonino’s Penshurst Pizzeria [Penshurst, Sydney]. What was the source of your inspiration?

Tony:

Well, being a musician, you live on takeaways. I didn’t like hamburgers; I didn’t like meat pies … I liked pizzas. A friend of mine had a pizza shop, so on my nights off, I used to go and help him. And I sort of quite liked it because he had the interaction with people all the time. I didn’t miss music all that much at first, because I enjoyed making pizzas. And it stuck with me — I’m still making pizzas.

For the first couple of years, I worked for this friend of mine, learned the trade, and he helped me open up a pizza shop. ’78-’79 is when I first opened my first pizza shop.

Andrew:

You’ve also been invited to play drums for numerous ACϟDC tribute bands. Tell us about that.

Tony:

Well, most of the bands that I’ve been involved with, they are Bon Scott tribute bands. And it relates a lot to the songs that I recorded with ACϟDC. So, Bon Scott Experience is one particular band from Italy; it’s Overdose ’74 from Italy; it’s Pure/DC from Spain. I’ve been invited to play some of the songs of the Bon Scott era, which is a privilege to me, and it’s something that’s very close to what I laid down with ACϟDC. So, it’s been great. There’s also Bon But Not Forgotten from Australia that I normally play for. Another band, Dirty Deeds, is a Bon Scott tribute band. So, it’s been a resurrection of me 40 years later. I’m enjoying it very much.

Andrew:

When you walked away from the music business in 1976, did you ever expect to sit behind a drum kit again?

Tony:

I never thought of me playing again at all because, with a pizza shop, you work at night. You don’t have time to go and see bands or interact with other bands. So, I put it away for 38 years, until Jesse Fink came along and asked a few questions. Then when the book came out, another Australian band, The Choirboys, which I admire very much, asked me to do High Voltage with them for the 40th Anniversary. And I’ll tell you what — I was so nervous. I almost said, “No,” until — I’ve got two sons, and both of them never heard me play live — and that implored me to do High Voltage for the first time in 40 years. After that, all tribute bands around Sydney and Europe wanted to play with me. So, I started again!

Andrew:

Well, Tony, I greatly appreciate the time and opportunity to share some of your story. There’s a lot of people out there that have a profound appreciation and respect for what you’ve accomplished.

Tony:

That’s nice to hear. I’m overwhelmed, really, because I never thought that seven years ago I would ever touch the drums again. When I got asked to play with The Choirboys, I actually told them that my drums weren’t good enough to play or rehearse on it. And all the fans all over the world put up some money … $20, $30, $40, $50 … for me to get a new set of drums. So, that in itself, I know there are a lot of people out there that would like to see me play. I’m overwhelmed and very thankful. If I can still walk, I’ll be still playing “High Voltage Rock ‘N’ Roll.”

Interested in learning more about ACϟDC’s High Voltage? Check out the links below:

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vinylwritermusic.wordpress.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

Leave a Reply