All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

By Layne Partin

laynepartin5@gmail.com

I’m not much of a fan of the saxophone in rock ‘n’ roll, at least not when it sounds like the musical equivalent of loud flatulence. But the sax is a part of rock ‘n’ roll, and that is in part thanks to Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street.”

With apologies to Bob Seagar’s “Turn the Page,” “Baker Street” has arguably the greatest saxophone riff in rock history. It’s so great that it resulted in what was known as the “Baker Street Phenomenon,” when the song caused a massive surge in sales of the instrument and its use in music, television shows, and commercials. It was Rafferty’s biggest hit, and it’s easily his most recognizable song, but there’s more to Gerry Rafferty than just “Baker Street.”

Gerald Rafferty was born on April 16, 1947, in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland, to working-class, Irish Catholic parents. His early exposure to music came from his mother singing traditional Irish and Scottish songs to him and the music of the Catholic mass. As a teenager, Rafferty and his two brothers listened to pop music on the radio, and he was drawn to Elvis, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the Band. Rafferty’s father was a second-generation miner and lorry driver who died when he was sixteen. Rafferty dropped out of school afterward and worked several odd jobs but never considered making a career out of them; there was never any doubt in his mind that his future was music.

“I played with local bands, and when I was about seventeen or eighteen, that’s when I first met Joe [Egan],” Rafferty reflected in an interview with Zigzag Magazine. “He was playing in a band called Censors at the time, and he was the lead singer. They were a band from Paisley who just played at weekends, and they needed a rhythm guitarist and vocalist, so I filled that position. And something sparked off between Joe and me immediately because we’d both been keen on the Everly Bros., and we could sing quite well together. He was the first guy that really sparked anything off, and it was really close, and it’s still close. So, we played in this band, the Censors, at weekends for a year or so, and then we played in a band called the Mavericks for another two years.”

In 1969, Rafferty became the third member of a folk-pop trio, the Humblebums, along with Billy Connolly and Tam Harvey. When Harvey left the group, Rafferty and Connolly continued and recorded two albums for Transatlantic. At a performance at the Royal Festival Hall in 1970, Rafferty received praise from critic Karl Dallas, who noted, “Gerry Rafferty’s songs have the sweet tenderness of Paul McCartney in his ‘Yesterday’ mood.”

The Humblebums separated in 1971, and Transatlantic signed Rafferty to a solo deal. He recorded his debut album, Can I Have My Money Back? and while critically acclaimed, it failed to garner commercial success. Around this time, Rafferty read The Outsider by Colin Wilson, a book about alienation and creativity. Rafferty identified with the book, and it became a “persistent theme” in his songs. In 1972, Rafferty rejoined Joe Egan and formed Stealers Wheel. They recorded three albums but were stunned when “Stuck In The Middle With You” became an international hit. Despite Egan’s pleading, Rafferty quit Stealers Wheel due to the stress of touring.

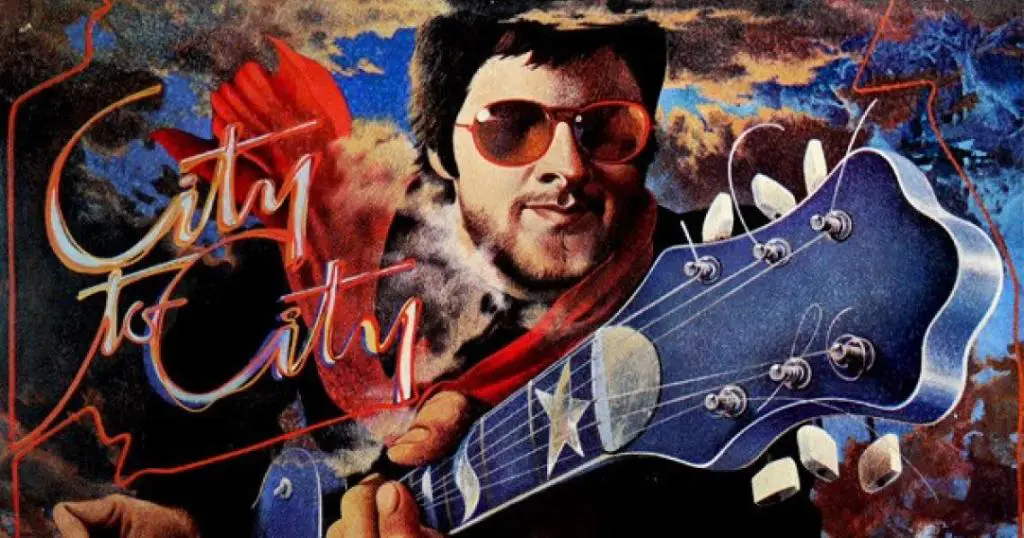

After again parting ways with Egan, Rafferty could not release any material for three years due to contractual issues and because “everyone was suing each other,” but he was far from idle. After the problems were resolved, Rafferty released his second solo album, City to City, which included “Baker Street.” Rafferty reportedly had to beg United Artists to release “Baker Street” as a single.

Thankfully, they complied, and “Baker Street” was released a couple of weeks after the release of City to City in March 1978. It became a No.2 hit in America and a No.3 hit in the UK. In July of 1978, City to City topped the American Hot 100, knocking the Saturday Night Fever Soundtrack from its perch. It sold 5.5 million copies on the strength of two more singles, “Right Down The Line” and “Home and Dry, which made it to No.12 on the Hot 100 and No.18 on the US Top 40, respectively. Rafferty later told Melody Maker that City to City was his first true success, saying, “All the records I’ve ever done before were flops. Stealers Wheel was a flop. Can I Have My Money Back? was a flop. The Humblebums were a flop. My life doesn’t stand or fall by the number of people who buy my records.” But suddenly, much to his dismay, Rafferty was an international star.

The lyrics to “Baker Street” reflected Rafferty’s disillusionment with the music industry, “This city desert makes you feel so cold, it’s got so many people, but it’s got no soul, and it’s taken you so long, to find out you were wrong when you thought it held everything.” Music journalist Paul Gambaccini confirmed this: “His song ‘Baker Street’ was about how uncomfortable he felt in the star system, and what do you know, it was a giant world hit. The album City to City went to No.1 in America, and suddenly he found that as a result of his protest, he was a bigger star than ever. And he now had more of what he didn’t like. And although he had a few more hit singles in the United States, by 1980 it was basically all over, and when I say ‘it,’ I mean basically his career, because he just was not comfortable with this.”

This might be a bit unfair; just because Rafferty never topped his peak achievement didn’t mean his career was over. The fact that he was uncomfortable with performing live and wasn’t a people person had more to do with the decline, so much so that Rafferty canceled a planned tour in support of City to City. Rafferty’s daughter Martha told the Daily Record in 2011: “He was planning a tour of America but was scared by the momentum he was generating and the kind of people his success attracted.”

While Rafferty might not have cared for certain aspects of the music industry, that didn’t keep him from continuing to write and record music and even touring on his terms. Rafferty’s follow-up to City to City, Night Owl, was released in June 1979, and while it didn’t do as well as its predecessor, it did manage platinum status in Canada and gold in the UK and the US. The title track reached No.5 in the UK, the album made the Top 10 there, “Days Gone By” reached No.17 in the US, and “Get It Right Next Time” made the Top 40 in the US and UK.

Rafferty’s follow-up records, Snakes and Ladders (1980), Sleepwalking (1982), and North and South (1988), fared worse. And Rafferty recorded two albums in the 1990s, On A Wing and a Prayer (1992) and Over My Head (1994). In 2000 he released Another World, and thanks to new technology and the Internet, Rafferty no longer needed the music industry to put his music directly into the hands of his fans, “At my time of life, I don’t want to be talking to 23-year-old record executives who are just trying to sell their products to 19-year-olds,” Rafferty told the Evening Standard. I’m older, and my audience is older. So, they know where to find me.”

In November 2009, Rafferty released his final album, Life Goes On. Gerry Rafferty died in 2011 from liver failure after a long battle with alcoholism. One has to wonder if he would have been pleased or appalled at the outpouring of tributes and honors after his death, revealing just what his music had had on generations of musicians. We’ll never know, but it’s not a bad legacy for a man who shunned the spotlight and would rather observe than be observed.

All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

– Layne Partin is a contributor for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at laynepartin5@gmail.com

Leave a Reply