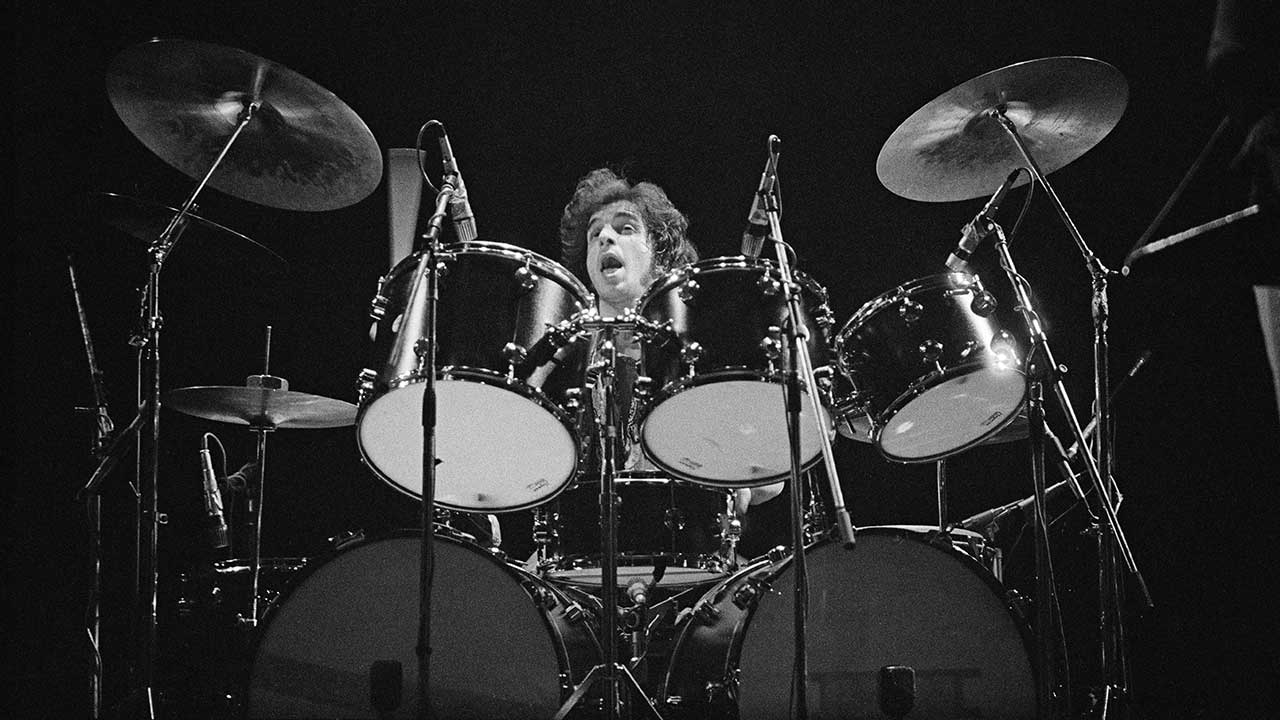

All images courtesy of Corky Laing

Mountain is one of the most underappreciated Hard Rock bands of all time. The most overlooked member of this underappreciated group is Corky Laing.

Corky turned his time with Mountain into a music career spanning five decades. In that time, he has been in other influential Hard Rock bands (Bruce, West & Laing), cult Indie bands (Cork), making thematic music, and being a music executive. Corky is a hard-working, and dynamic person who has truly done it all.

Furthermore, Corky is an astounding storyteller with so many unique, and valuable memories.

During my sit down with Corky, we discuss his new book (Letters to Sarah), the making of the classic album Mountain Climbing!, why Bruce, West, and Laing was such a short-lived project, what it takes to sustain such a long career in the entertainment industry, and so much more. Go here to learn more about Corky Laing.

Joe:

What have you been up to the past year considering the current state of the world?

Corky:

In short, I have been spending a great deal of time in Finland. I ended up going over to Finland because that’s the only way I could navigate under the current situation. I made some recordings with friends there. Some friends that are exceptionally fine musicians. They were from the Helsinki Orchestra, trumpet players and percussionists, and so on. I experimented a great deal over there. My manager and my favorite person in the world, Tuija Takala, has a wonderful country house there. While hanging out there, I started taking dips in the ice-cold water. There’s a lake there, and it’s freezing. You dip in to wake yourself up, and it really wakes you up. Really, really wakes you up. It was actually a regular routine there. Going in the cold water, I felt like a man, you know. I’m Canadian, and you’d think that I know about that shit but no. [Laughs]. It was amazing. I did a lot of creative work there that I didn’t plan on doing—recorded quite a bit of thematic music. I have a close friend who’s an actor and director, and I sent him the music I wrote for a potential movie. For example, I would write a piece for a possible chase scene. I just envisioned a lot of different things that could be because there were a lot of things that could not be. It was challenging, but I would say that was the gist of what I was doing. I like to keep myself busy and stay away from the negative shit.

Joe:

Tell me a little about this book of yours that came out recently.

Corky:

Well, I’ve got some terrific feedback on it. It’s not a book about snorting ants off tables or something like that. The book is called Letters to Sarah. It’s centered around a series of letters I wrote my mother over the years. In part, it’s about growing up as a musician in Montreal. It’s not about Rock, per se. Every time I was on the road touring, I would write my mother to stay relevant and on her good side. I come from a big family; I have triplet brothers and a sister. It would be four in the morning, and I would be alone in the hotel writing her letters. I just played Carnegie Hall, and I would be writing mom. I didn’t realize she saved those letters. She kept all the letters this whole time. My manager helped me make sense of them by organizing them chronologically. Then we turned it into an entire book. Get it at your favorite store and read the damn thing. [Laughs].

Joe:

Shortly before Mountain, you were in a band called Energy. As I understand it, Two Mountain staples, “Mississippi Queen” and “For Yasgur’s Farm” were initially written with that band. How did they make their way onto the first Mountain album?

Corky:

Originally, we were called Bartholomew Plus Three. We were just going through that change of the 60s into the 70s. For the time, our band was considerably prolific. George Gardos, the bass player and my oldest friend, would write songs with me. We were writing our own material way before it was commonplace.

Felix Pappalardi had yet to produce Cream; he had just finished producing The Youngbloods. Felix initially came up to Montreal to work with Energy to record “When I Fall in Love” for Atlantic Records. Apparently, Ahmet Ertegun wanted to do an updated version. We recorded it and sold about three copies. [Laughs]. It was a great production, though.

An explosion in my life then started when Felix said, “Do you have any new material?” When we played the original stuff, Felix fell in love with our melodies. Energy’s melodies were surprisingly good. From there, Felix had started to produce our record, but he got a call asking him to produce Cream. So, he had to give up producing us at the time. He had eleven or twelve days to produce Cream and make Disraeli Gears. Once he completed that album, everything blew wide open for Felix. During that time, he also produced Leslie West’s solo album, Mountain.

When we started off trying to make Mountain Climbing!, we didn’t have any material. Leslie had just done his first record and didn’t have a chance to write any new songs. Felix was so busy with various things at the time, which didn’t make coming up with new material any easier. Felix had remembered the Energy stuff and how much he liked the songs that George, Gary ship, and I had written. One of those songs being, “Who Am I But You and the Sun,” which became “For Yasgur’s Farm.” Another song was “Mississippi Queen,” but it wasn’t a full song yet. It was just a riff and me screaming and ranting, “Mississippi Queen, do you know what I mean?” Felix had a way of taking the songs and Moutainizing them. We were sort of a Pop band, and Mountain was not ever a Pop band. Moutain was Hard Rock, sort of on the verge of Heavy Metal. So, there was “For Yasgur’s Farm,” “Silver Paper,” etc., that really stemmed from Energy. They also happened to be the more accessible and radio-friendly songs compared to some of the other Mountain material. That’s how it came about.

Joe:

Sadly, you are the last living member of the original lineup of Mountain. Felix, passing away back in the 80s, and Leslie a few months ago. It seems like the three of you had a special relationship. You worked together so often in the studio and on tour, on and off over the years. What made that relationship between you three so special?

Corky:

I am the last man standing on the mountainside. By the way, I take no pleasure in it. I wish everybody was still around. The relationship between Leslie and Felix, that was electric. That was powerful. That was of the nuclear kind of vibe. Each of them had what the other one needed. That’s what is essential in any band or relationship. You don’t want to join up with somebody with the same talent as you. You want it to be different. Felix was a doctor of music. Leslie knew nothing about music except how to create it. All of Leslie’s gut feelings were able to be translated through Felix. I just happened to be the icing on the cake. It was a tasty thing to be because those guys had enough rhythm. They didn’t need a fucking drummer. I just sat there and played my percussion stuff. I enjoyed that relationship, and I fit in like the Henry Kissinger of Rock.

It was just the luck of the draw in terms of how it worked out. I think there’s a four-letter word in Rock. It’s called luck. You have to have a lot of luck. Leslie and Felix were brilliant when they were doing what they do best. There was nobody that could do it better. All I could do was really push it and beat the shit out of the drums. I couldn’t hear anything else because they had stacks on both sides of me. I had to bang as hard as I could. I think, in part, we became associated with Heavy Metal bands because I was playing on metal to get through that sound.

Joe:

Do you have special memories or anecdotes about Leslie or Felix or just generally regarding Mountain?

Corky:

‘69 to ‘72 was one big musical party. It was an explosion of fun and musical experimentation. We had tons of good times with so many other bands. I forget how many shows we did with Ten Years After, Traffic, and Mott the Hoople. The Eagles opened a lot of Mountain shows in those days. I was a big fan of their first record. I can’t point out one moment. The biggest moments were when Mountain was at its peak, in the early 70s. It was all passion. People talk about the drugs and this and that…they can always have the other shit that goes into it. To be a teenager in the 50s was to be a nobody; to be a teenager in the 60s was to be an everybody. When you become a musician and a successful one at that, it doesn’t get any fucking better. Anybody still alive will tell you it was the beginning of the best days of their lives. To name a particular thing is tough because there are a million.

Joe:

Mountain was such an influential band in the evolution of Rock music. Generations of music lovers continue to listen to that music to this day. What do you think the legacy of Mountain is, and what does it mean to you?

Corky:

I mean, I’m still enjoying the material. That’s the legacy, the material, and the albums. There are thousands of people all over the world still relishing this music. I’m still playing the material the best I can. I’m going out there with a Mountain featuring myself because nobody else is around. The fact is it’s the material we have that people remember. They weren’t all hit records, but they were credible musical compositions. We had Felix, who was a brilliant composer and arranger. Then you had Leslie, who could bring in the substance, the real stuff. I think they call it a diamond in the rough. Leslie would bring that in. The truth is, I’m humbled to this day, having the opportunity to play with Felix and Leslie. Being able to play with Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton are unforgettable moments. Being able to relive those moments is what was is so great about the music.

I’m sorry to say Leslie just passed. Oddly enough, he was never properly appreciated back in the day. Jeff Beck, at one point, said he was the best guitar player in Rock ‘N’ Roll. Peter Townsend and Jimi Hendrix loved Leslie. We all played together, and there were some incredible moments. I lived in The Village during the Mountain days. Everybody was there and walking the streets. I used to sit out on the fire escape, like an old Italian lady. I would just watch what was happening on MacDougal Alley and MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. It was brilliant, but that was all part of the era. I miss it terribly, but it is the past. I do plan to keep on going and make new memories. Make even better memories if I can.

It’s like when somebody stops me on the street and says, “Hey Cork, remember when you were at the Capitol Theater? I was sitting in the third row, and you tripped over this, and you fell.” And then I go, “Wow! I do remember that.” You’re sharing a moment with somebody that was really there. We have a great fan base, and at this point, they are friends. Thousands of people share those moments, and they’re very intimate.

Joe:

Moving away from Mountain, let’s talk about some of the other projects you have been in over the years. You and Leslie formed a short-lived group with Jack Bruce. I have to say, those were two terrific albums. How did that group come together, and why was it such a brief project?

Corky:

In 1972, Felix said he wanted to take a break from Mountain because he had problems with his ears. I think he was just burnt out from doing a million things at one time. He was involved with so many different projects as both a producer and a musician. Leslie and I, well, we were just getting into it. We felt we were just reaching our peak. The two of us decided to go over to England. At the same time, Jack Bruce was coming back from a tour in Europe. We had met each other because Felix had produced Jack’s records.

The president of Island Records was trying to put together some supergroups because Mott the Hoople and Free broke up. Of course, Leslie and I were also free to do things. He booked the studio for us at Island Records. We would go jam with Paul Rogers, Overend Watts, and others. They were great jam sessions. We played a song called “Sail On” with Paul Rodgers; it was a great moment. After we started doing these jams sessions, Leslie told me Jack Bruce had called. He told Jack to come down and jam. We booked a couple of days to play with Jack. We played all night, and we recorded a lot of that stuff. There was so much energy, and Jack was ready to blow up. You know what, so were we. So, that’s when West, Bruce & Laing got together.

Robert Stigwood, the manager for Cream, was hanging around these jam sessions. Robert said, “Wait a second, why don’t we book these guys. This sounds good. The three of them as a supergroup.” They put it together and decided to call us West, Bruce & Laing. We didn’t know what was going on, but they had apparently already booked a sold-out tour in America. This was before we even had a record out. It was word of mouth, and it was a lot of pressure. All that pressure wasn’t good. We were in the studio jamming and trying to write. We busted our asses getting that record together. Quite frankly, I think the record could have been a lot better had we gotten the proper time to make it. But suddenly, we had a deadline. We had to get this record finished in April because we were going to tour in May and June as West, Bruce & Laing. It came together in a rush. We barely had the contracts or anything together. We had a couple of very greedy managers. They got in there and started squeezing everything they could out of the record companies. It was a fiasco.

We were rock stars before we were a Rock band. They said we were going to be bigger than Led Zeppelin. It was crazy, and it was too much too soon. We managed to squeeze two or three records out of it. I would say they were very influential records. A lot of bands took direction from them, like Mötley Crüe. Tommy Lee came up to me once and said they stole so many ideas from West, Bruce & Laing. He started naming all these West, Bruce & Laing songs. Of course, we had the logistics of Jack being in England, me being in Canada, and Leslie being in New York. We were never able to finish any great songs; that was the main problem with West, Bruce & Laing.

Joe:

Can you tell me a little about how Secret Sessions by Corky Laing’s Pompeii came together? How were you able to get that many of your amazingly talented friends on one album? Why did it take so long for it to be officially released?

Corky:

It’s a compilation of different recording sessions. It came about over 20 to 30 years, and we called it Secret Sessions because nobody knew about it. Ian Hunter, Mick Ronson, and I had done some recordings together. Ian Hunter and I used to record at Levon Helm’s barn. We used to joke about recording there because the locals referred to us as the dinosaurs up on the hill in Pompeii. Somehow, we ended up remembering it and, out of irony, used the name. I did some sessions with Eric Clapton too. He played on my first solo album, Makin’ It on the Streets, as well. I ended up crossing paths with a lot of musicians. Some of the songs that we put together and recorded were pretty fucking good.

Secret Sessions went through a couple of record companies that didn’t quite have time to put it out. Finally, buddies of mine in Detroit picked it up and said, “Why don’t we put this out as a compilation.” So, these different projects came together, and I took the best of each project. I gave it to them to see what they could do. Eventually, they came out with it on vinyl, and it sold out. It did well because it came out on Record Store Day. They decided to print a couple of hundred more, and those sold out too. It turned out that they sold over a thousand. They kept on pressing more and more as they got additional preorders. It ended up being a highly successful project.

Joe:

Your project, Cork, with Eric Schenkman, is an incredibly unique one. How did that come together? Any chance of new music from that avenue in the future?

Corky:

It’s funny you mention Cork because Speed of Thought is one of my favorite albums I ever recorded. Eric Schenkman is brilliant. Way back in the early 90s, I worked for Polygram Records. I was vice president, and I had a great job. I was sent this one record, and it was the Spin Doctors. I thought it was rocking and had this cool R&B aspect to it. Eric Schenkman, who was in the Spin Doctors, was the guy that sent it to me. So, that was how I first met and became familiar with Eric.

Sometime after that, I crossed paths with Noel Redding in New York. Eddie Kramer was putting together another one of his lost Jimi Hendrix tapes. They called in Noel and Eric to play. We were all in the studio, hanging out since we’re all friends. Eric mentioned we should get together and jam in Toronto. Noel said, “Well, wait a second. What about me?” Noel came to Toronto so we could all play together. Then we started playing live. We played this Blues club called The Carwash in New York. The three of us were just jamming out and having a great time. Eric’s a great guy to play with because his time and rhythm are fucking great. A label called Light Year Records heard about us jamming. They wanted us to make an album for their label. Eric and I got together, and we started writing. Eric is a fantastic writer. He doesn’t just write a song. He envisions an entire landscape, and he writes about it. He’s very prolific. Anyway, we took those songs and recorded Speed of Thought. Eventually, we did the second one, Out There.

I would very much like to do another Cork record, and Eric does as well. As a matter of fact, Eric just called about a month ago, and he wants to get together. So, what is going on with Cork? Cork is still around. It’s in the air.

Joe:

Let’s talk about the drums for a second. One of the unique things about the drums is that it has so many moving parts. Many drummers have their own unique setup. Do you have your own standard setup? Or is it different depending on who you are playing with or in the studio or touring? How has it changed over the years?

Corky:

The first thing that comes to mind, given your questions, is when Leslie and I were touring in the 80s. It was a dark period for us, and we played a lot of clubs. In order to save money, Leslie would make sure the opening band left their equipment on stage for us to use. I would use whatever drums were there, and it was very cool in a way. I would make use of whatever was there. If they had beautiful tom-toms, I would concentrate on those. If they had great cymbals, I would focus on those. Leslie hated cymbals. During my tenure in our dark period, Leslie would always yell, “Could you keep the fucking cymbals away from me.” He would even take the crash cymbal off the stage during some of the shows and throw it somewhere. That had a lot to do with me staying with the tom-toms during that period. [Laughs].

Anyway, If there’s a skin in a barrel, I’ll fucking hit it. I’m not particularly delicate about that. I play whatever is in front of me and get the best sound to suit the song. I have had a lot of drum sets. I was fortunate to get drums from everybody during my time, and I took them. My favorite was a beautiful set of drums from Haymen. They started making them in England, and I had a set made for me. Mitch Mitchell, from Jimi Hendrix’s band, was the only other guy I knew that had the Haymen drums.

I had a lot of drums, but I didn’t want to keep them in the garage. I kept bringing them to studios and asking them to take care of sets for me. I knew they would get played and be cared for at the studios. I must have had two or three dozen sets of drums in studios all over the U.S. and Canada. I left drums everywhere.

I’m still looking for my original set. The one that I played in the early days of Mountain. The unique thing about the set is that it had a smaller bass drum. In those days, I couldn’t afford a bigger bass drum. Everybody always wondered why I used that model. They speculated it was because I was looking for different tones. I didn’t want to admit to them that it was the same reason I used timbales instead of tom-toms. [Laughs]. I couldn’t afford anything else, but I always made it work. In desperate times it comes together.

Joe:

You have such a storied past in the music industry. It has enabled you to work with many different musicians/songwriters/ producers. Is there anyone you have not had a chance to work with that you would like to in the future?

Corky:

I don’t know about the future, but Elvis Presley is the first person to come to mind. I love watching videos of him and seeing him do the martial arts thing. I think it would be fun, you know, to fucking punch this and punch that on the cymbals. He always had a great band.

I was fortunate to sit down and have breakfast with Leonard Cohen. He’s not a rocker, but he is a very prolific writer. We had a lot in common because we’re both nice Jewish boys from Montreal. I never got a chance to play with him, but he did invite me to play. I guess he would be another one, again obviously not in the future, along with Elvis.

That being said, I have had the opportunity to work and interact with some amazing people. I even played with Levon Helm, whose one of my favorite all-time fucking people. I’m fortunate. Gold records. Carnegie Hall. All that stuff. It’s not what is important. It’s the people you meet along the way.

Joe:

As I mentioned above, you have such a storied past in the music industry. Many talented people such as yourself have shone brightly only to flame out rather quickly. What does it take to sustain a career in the music and entertainment industry?

Corky:

Well, I think curiosity would be the main thing. I’m very curious. I hear music, and then I start to wonder. How do they do it? How can I play this? I watch drummers and copy them. I sat behind Keith Moon when he was at Madison Square Garden. I was studying Keith because he was an excellent fucking drummer. He’s not what you would call a timekeeper. He’s a performer. I remember watching every move he made. I’m good that way. I can do it just by watching. Keith gets off the stage, and as we walked out, I tried to ask him about his playing. He screamed, “Don’t fucking ask me anything. I don’t know what the fuck I just did, so don’t even ask me. All right?” He’s yelling at me, of course, in a fun way.

Anyway, back to the question. What does it take to be resilient? You have to stay with the program. You’ve got to be interested, and with that comes commitment. I remember one of the producers came into my office when I was working at Polygram. He said, “Did you hear this song? Listen to the bass drums.” Remember, I was sitting behind the desk at that time. I was an executive, but I went home that night to my drums downstairs. I went down to play every day for three weeks straight. Every time I went down there, I was just trying to find that drum part the producer had shown me. Personally, those are the type of moments that have sustained my career in music.

Even now, I am always learning. I go to videos on Drumeo. It’s an online drum school. I go to them and watch different drummers who highlight snare drum techniques. I am 73, and I’m still curious. I don’t know why. There’s no fucking gigs. [Laughs]. It’s just the curiosity in me. I guess I’ve always felt that.

Interested in learning more about the artistry of Corky Laing? Check out the link below:

Dig this interview? Check out the full archives of Records, Roots & Ramblings, by Joe O’Brien, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/records-roots-ramblings-archives/