All images courtesy of Matt Thorne

A veteran of the Los Angeles music scene in the 1980s, Matt Thorne experienced the inevitable highs and lows of the music industry before discovering a passion that would change his career path.

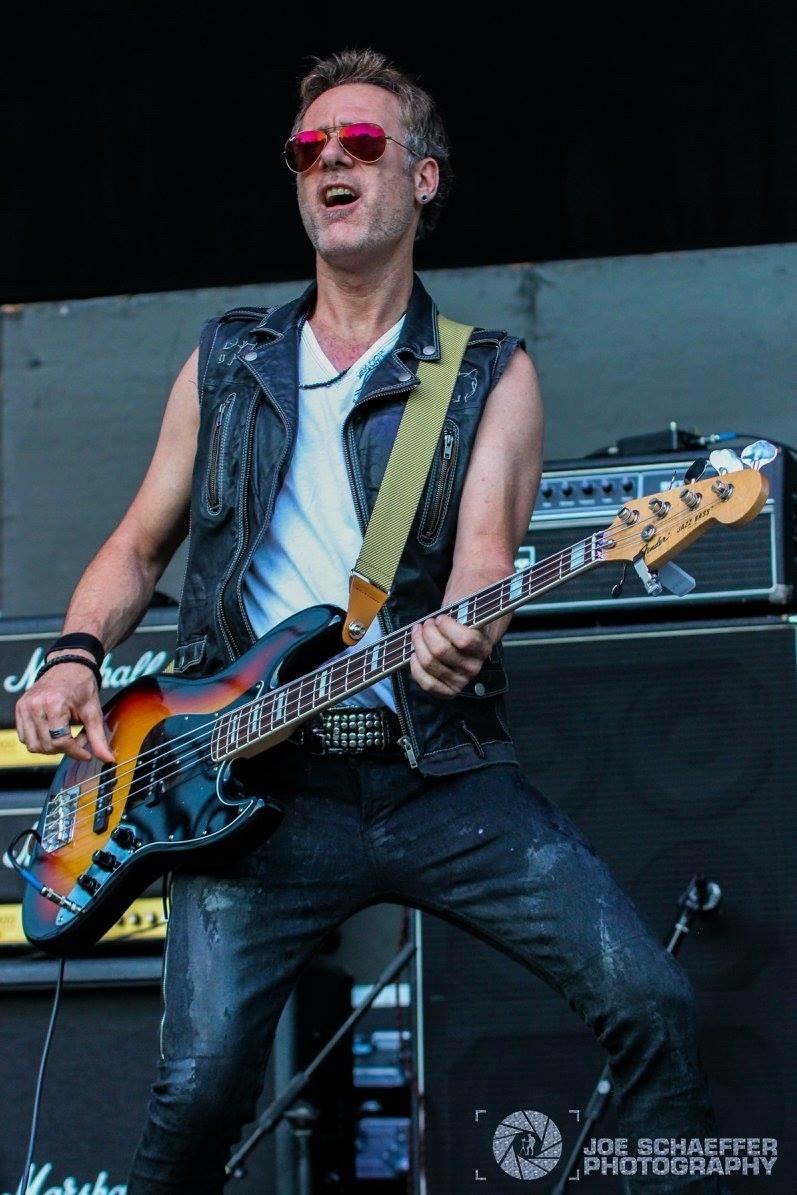

A bass player by trade, perhaps best known for his work in prominent LA bands including, Ratt, Rough Cutt, and Jailhouse, Thorne ultimately transitioned to the production side of the business shortly after the decade turned, opening the doors to his studio, MT Studios, in 1995.

Thorne’s clients over the years have included The Eels, Disturbed, and Trapt, among others. His fingerprints can also be found on various other ventures, including television, film, and advertising.

Matt and I discussed his roller-coaster career in the industry in this career-spanning interview.

If you haven’t already, be sure to check out Matt’s most recent effort, Rough Cutt 3, released in June 2021 via DDR Music Group, which reunites Thorne with vocalist Paul Shortino, and guitarist Amir Derakh. The 10-track album also features guest appearances from virtuoso guitarist Carlos Cavazo, formally of Quiet Riot fame. Rough Cutt 3 is available in both digital, and physical formats.

Andrew:

You were coming up amid a booming music period in California, Matt. What do you recall from your introduction to that scene?

Matt:

Well, what happened with me is, I was living in San Diego throughout my teens. I knew a bunch of people that were in San Diego, and San Diego was a nowhere land; you really couldn’t do anything with music there. It had a great music scene, but there were no eyes on you there, so a lot of people were thinking of moving to Los Angeles, and I did when I was nineteen years old. So, I missed the 70s in L.A.; I’m from L.A., but in my teen years, I moved to San Diego. I was pretty serious about becoming a musician, so I moved to Los Angeles, I would say it was 1981. That’s when I started visiting the club scene, which was, at the time, the end of The Starwood years and The Troubadour. There wasn’t a lot of activity at The Whisky and The Roxy yet on a local level.

So, I think the first band I saw at The Starwood was called DuBrow, which was Kevin DuBrow’s band. Rudy Sarzo was in it; I think Carlos [Cavazo] was in it, too. I don’t think Stephen Quadros was in it. So, that was the amalgam of a band called Snow. Snow was led by Carlos — I never saw Snow — but there was a guy named Doug [Ellison] I think, that sang. There were a couple of big bands at the time; A La Carte; Snow. I kind of missed them. When I moved to L.A., I just missed out on those Starwood bands, and there were these bands that were sort of offshoots of those bands and I was seeing them, like Dante Fox, which I saw at The Troubadour.

I missed a lot of it, so my background in music was more in San Diego, and we were moving to L.A. to get more eyes on us.

Andrew:

When you decided to relocate to Los Angeles, did you know anyone in the area, or was it purely a leap of faith?

Matt:

So, I moved up here with Jake, who was Jake Williams at the time and became Jake E. Lee. I was in a band with him in San Diego, and he was one of the better guitar players in San Diego. He actually convinced me to move to L.A., so we moved up here together, and got a house in Van Nuys. [Jake] was really the only person I knew in L.A. I didn’t really know Stephen [Pearcy], and the guys from Ratt, but when I got here, I started going out and meeting people. I was in two bands simultaneously, so it didn’t take me long to get to know people. It was a little scary at first, then I just started going out with Jake and we would meet people. Jake got in Ratt really quickly and was playing Gazzari’s. Then, shortly after Jake got in Ratt, they needed a bass player, so I got in Ratt. It was quick. I was probably here for three months, and I was already in a band, and then I got another band right away. I was doing rehearsals and playing gigs all over the place.

Andrew:

Now, did you have to audition for Ratt, or were you offered the slot off of Jake’s recommendation?

Matt:

Well, I did kind of have to audition. It was like was one of those things where, you’re auditioning, but you’ve got a good in. So, I did have to audition, and it was kind of strange because Stephen had these tapes he would him with him playing guitar — no vocals, no bass, no drums, just him playing guitar — and that’s what he gave you to learn the songs. You didn’t even know how they were gonna go. You just thought, “Okay, here’s the music. I’m gonna show up there and play my own bass line, my own…whatever I make up, and that’s gonna be it.”

Andrew:

What original songs did Ratt have in their catalog by 1981?

Matt:

A song called “Out Of The Cellar,” which I don’t think ever was recorded, but that was the name of their first record. “In Your Direction,” which was on Out Of The Cellar, and “Never Use Love,” which was on Invasion of Privacy. That was the first batch that I learned. Those were the ones that stand out to me; they had “Driving On E.” I can’t remember them all, but there were a bunch of songs that never ended up on the records.

Later on, when I was in the band, Stephen and I sat down and wrote “Back For More.” I never played that in the band, because I quit shortly after we wrote the song, but I did hear them play it at the place they were rehearsing when I went to pick up my amp. But the songs like “Round And Round,” we weren’t playing those songs. There was another song that I co-wrote with Warren [DeMartini], which was “The Morning After,” and that ended up on Out Of The Cellar. Most of those songs I didn’t play; just “Never Use Love,” and “In Your Direction” were the only two that I think ended up on Out Of The Cellar.

Andrew:

Obviously, you were in the band for a brief period, Matt, but that happened to be a thriving time for music, with Mötley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Dante Fox, and Dokken among the many notable acts. What are your memories of playing gigs on The Strip with Ratt?

Matt:

When I first got to L.A., I didn’t think the bands were very good. I thought the San Diego bands were better. Then when I went and saw Mötley Crüe, it changed my mind. I thought Mötley Crüe was gonna be huge. I just thought they had good songs; they had a cool look; people were into them. The first time I saw them was at The Troubadour. So, that was the first band that I thought, “Wow, this is what you need to be. This is superior.”

The Dante Fox’s and the DuBrow’s, I couldn’t remember any of their songs, so there was this period where there were a lot of bands, but they weren’t doing anything. Then Quiet Riot came. They were the first band to break out after the Van Halen era. You had this big gap where nobody was getting signed; record companies didn’t even go to shows. Then all of a sudden, Quiet Riot hit, and they’re on the radio, and they sell five million records on that [Metal Health] record. Then it opened up doors for Pop Metal. Then the next in line was Mötley Crüe, who already had a full-length album — but it was on Leathür Records — and then Elektra Records picked them up and put it on Elektra. Then they put out Shout At The Devil, and they went double platinum. But it took Motley a while. I remember talking to Nikki [Sixx] backstage at The Troubadour, and I go, “So, you guys are doing pretty good…” He goes, “We haven’t even gone gold yet.” And that was their Too Fast For Love record that was on Elektra. So, it was slow. But when Shout At The Devil came out, then they all went platinum. But [Quiet Riot] opened the doors to that kind of music, since radio wasn’t playing that kind of music.

The Ratt came out with “You Think You’re Tough” on an EP, and they were getting on a local radio station called KMET. And KMET was playing them throughout the day; they were on heavy rotation. So then, all of a sudden Ratt was selling out Santa Monica Civic Center. It opened the doors for all these bands.

Andrew:

You mentioned writing “Back For More” with Stephen, a song that remains a setlist staple to this day. What is your recollection of the origins of that song?

Matt:

I wrote the intro riff on bass. There was this house in Culver City called “Mrs. O’Neal’s house.” That’s all I knew. I never even saw “Mrs. O’Neal,” I don’t know who Mrs. O’Neal was, all I saw was this St. Bernard dog. That’s it. There was this back bedroom that Stephen occupied, and I went in there, sat down with my bass and he had a guitar, and I showed him the intro to that song and the chorus. He wrote the verse and the solo section, and the next thing I heard was them performing it in Mrs. O’Neal’s garage! That’s how it went down. It was that fast.

I was kind of shocked, actually, when I went and picked up my bass amp, and heard that song being played by Warren, Robbin, Khurt Maier, and I don’t know who the bass player was. Stephen was standing outside the garage, and I asked him, “Is that the song we just wrote?” He goes, “Yeah, man! It’s cool.” There was another song he and I wrote, called, “Ain’t Gonna Be Your Fool,” so I said, “I’ll trade you…I’ll take “Ain’t Gonna Be Your Fool and you take this “Back For More” song, and we’re good.” And that’s the deal we made. That was the end of it.

Andrew:

Obviously, no one had the foresight to know what “Back For More” would ultimately become.

Matt:

No, and when it did, [Stephen] comes over — I lived in another place in Van Nuys — and he came and said, “Listen, I could give you a gold album, or you could have this guitar. What do you want?” And the guitar was a white Charvel. And he said, “What do you want? We went gold and I gotta give you somethin’” So, I took the guitar because I was like, “I don’t want Ratt’s gold album! Why would I want Ratt’s gold album?” I wish I would have taken it!

Andrew:

If memory serves, Matt, you never received proper credit for your contributions. Was there ever an explanation as to why?

Matt:

They just didn’t do it. They gave me special thanks, and they spelled my last name wrong on it, which was more irritating at the time to me than not getting songwriting credits. Because I didn’t really know what the money for songwriting was. We were managed by Wendy Dio, and I asked her, “Should I be suing them for this?” And then she said, “No.” So, I said, “Okay.” I was friends with Stephen, and I wanted to stay friends with him. I didn’t wanna go down that road. So, I just said, “It is what it is. I’m a little bummed.” And later down the road, Stephen gave me credit, so I was OK. I think in 2005, or something he finally did.

Andrew:

You then bolted and joined the band Sarge, with singer Steven St. James and guitarist Chris Hager. What prompted you to make the move despite dabbling with early success?

Matt:

I was kind of dabbling in both bands, Ratt and Sarge. What happened was, Jake, quit Ratt, and I thought Jake was the guy. Warren, Jake, and I were living in the same house, and Warren took Jake’s place when Jake quit Ratt. And when Jake quit Ratt, I thought, “It’s probably not going to go much further.” I misjudged that one, right? So, I went to the other band that I was dabbling in, Sarge. [Sarge] had a pretty good following, so I went over there. Our singer, Steven St. James, quit, and joined Kagny & The Dirty Rats, which was on Motown [Records], with Marq Torien of BulletBoys. So, he split, and we were pretty much left holding the bag. We tried to get a singer from San Diego, and he wasn’t committing, so it just kind of fell apart. That’s when I joined Rough Cutt.

Andrew:

After watching Ratt subsequently vault to stardom, are there ever times where you find yourself second-guessing your decision to leave?

Matt:

Well, to be honest with you, I think it was a blessing that I didn’t become a Ratt guy. I’ve known a lot of people that have done really well in music, and sold millions of records. And there’s kind of a dark side to it because, for one thing, it doesn’t last very long for most people. It’s very short-lived; you got about one-to-four albums. If you get to four, you’ve really done well. But there’s a very big downslide that you’re going to have to deal with. That’s mentally hard to take, because you’re on top of the world, and then all of a sudden, you’re not anymore. You’ve had your ass kissed for, one-to-four albums, and now, all of a sudden, nobody cares about you. I feel like people have a hard time dealing with that. There are very few that can come out saying, “You know what? I’ve had a good run. Now, the next portion of my life, I’ll lead.” I think that there’s a blessing not having that because it forces you to deal with who you are as a person. And you aren’t this character of a person that you’re having to live up to. There’s not a lot of people that can handle that; that they aren’t the person they thought they were; that their identity is taken away, if you get what I’m saying.

I’m still in music, and I make the same living in music I’ve been making for the last twenty-six years. It’s consistent, and there’s no ego that goes along with it. It’s just what I do, and it’s who I am. So, if I went down that route of being super successful for a few years of my life, would I have been able to put on this other hat, and be OK with it?

Andrew:

So, if you could, take me through the events that led to you and Chris joining Rough Cutt, and subsequently signing a deal with Warner Bros.?

Matt:

When I was in Ratt and Sarge at the same time, I was not committing to Sarge. I was kind of stringing Sarge along, kind of like Juan [Croucier] did Ratt with Dokken. So, when it came to quitting Sarge again, I kind of felt a little guilty not to take Chris with me. I didn’t want to do that to him again. Rough Cutt wanted me, and I forced it to take Chris with me, and they were cool with that because they liked Chris. So, I said, “You gotta take Chris if you’re gonna take me.” It was kind of a package deal. And they had Ronnie and Wendy [Dio] involved, so I thought there was a good chance that something could happen with this band. It took a while, but eventually, we did get signed to Warner Brothers, after a showcase in Burbank in the early morning hours.

I remember Ted Templeman coming there. Our showcase was funny because it was supposed to be at ten o’clock in the morning — which is very early for a Rock band — and Warner called us and said that Ted Templeman had a headache and wasn’t gonna come. So, you could imagine how we were feeling. We were like, “Uh, we just set up and we’re looking forward to this showcase with Ted Templeman, Van Halen’s producer, who’s the vice president of Warner Bros. And they called and said he has a headache and isn’t coming.” Our whole balloon had been popped, and then they called back about forty-five minutes later and said, “[Ted] feels better now. He’s gonna come.” So, [Ted] came and watched us and gave us some comments after we performed, he asked us if we were willing to do a couple of things. We were really holding out that he would produce us if we got signed. Then, he left, and around late afternoon that day, a guy calls up when we were at our management office and said, “Welcome to Warner Bros. Records.” And then that was it.

Andrew:

In what ways did Ronnie James Dio make an impact on Rough Cutt?

Matt:

Well, he impacted Paul [Shortino] quite a bit. I loved how he produced Paul. He was very good with Paul and vocals. Out of all the producers we used, Ronnie, I thought, brought the best out of Paul. And you can really hear it on the demos we did with him; we did “Taker,” “Try A Little Harder”, and “Queen Of Seduction.” Three songs with Ronnie. And I still really like those three songs better than I think anything we did. Honestly. I wish we would have used him as a producer on our records; I don’t know why we didn’t.

What I thought was great about Ronnie, was how he was so giving. He would give, with everything he had, to help other musicians. He put his name, his time, his money to get us recorded well. He pitched us to Warner Bros. He took us on tour. He helped us individually; we when had nowhere to live, he let us live in his house. I mean, he was a great guy, and he really helped us to get to the point where we could spread our own wings.

Andrew:

With that said, Matt, even with Dio’s backing the band, why do you believe that Rough Cutt never quite managed to break through like many of its contemporaries?

Matt:

There were two reasons for that. One, to be successful, you need one song that is a one-listen hit; and we didn’t have that. Two, in 1984, MTV was the vehicle to get your song heard by the masses. That was the radio station pretty much. In early 1985, when our record came out, MTV changed their format; they were leaning more toward bands like Styx and Duran Duran. I don’t know what you’d call that genre, but they wanted to go more in that direction, and less of the Quiet Riot, Queensryche, Metal/Pop Metal bands. So, their new policy was no more new debut bands that are of this genre. They weren’t gonna play them. So, we didn’t get any airplay or any MTV viewership during that time because they just weren’t gonna do it. They would only play the ones that were established.

Andrew:

So, the band eventually petered out?

Matt:

Warner Bros. believed in us. We also didn’t have an A&R guy. Our A&R was Tom Whalley, who was kind of our cheerleader — that’s what an A&R guy is — they’re your cheerleader at the record company. And our cheerleader got a better offer over at Capitol Records. So, he left us with nobody there. So, now, you don’t have a cheerleader, you don’t have MTV, and you made a record that’s kind of leaning toward poppy on some songs, and a little more Metal on other songs. But you need radio to promote this record because it leaned toward Pop, right? So, with that said, you need MTV; you need radio. If you were to go more Metal, you actually didn’t need any of that; you could rely on Headbangers Ball. You didn’t need the daytime play because you were a Metal band, and Metal bands at that time were doing better than the Pop Metal bands in 1985. If you were tapping into that Metal audience, they didn’t like it if you were on the radio. You would really get that crowd. This is my regret; I wish we would have used Ronnie [Dio] as a producer because if we would have used Ronnie as a producer, we would have been geared toward tapping into that underground crowd and had fewer Pop elements. I think we maybe could have sold more records as an underground band. We wouldn’t have sold millions, but we might have gone gold instead of petering underneath that.

Andrew:

I know Rock Candy reissued the first two Rough Cutt albums. Did you notice any semblance of a resurgence as a result?

Matt:

What I saw happen was, this 80s kind of genre — I would call it a niche now — because there’s not a lot of fans, but they’re really hardcore fans of that genre. They love that music. They don’t like any other kind of music, pretty much. It started there, it stopped there. So, what I saw, because I was playing in Stephen Pearcy’s band, and we would go out and play Ratt songs; when I first joined, which was I think in 2013, we were having audiences, but they weren’t very large. They were probably three to five hundred people in clubs.

About two years later, I saw this huge difference; all of the sudden, we were playing in front of thousands of people. So, it felt like there was this big resurgence of that kind of music, in general. Like all of a sudden, these people, their kids are growing up now, and they don’t have to take care of kids anymore. They’re coming out of the house in their forties, and … “We’re gonna have a blast and go see the music that we loved!” So, I felt a huge resurgence of 80s music.

About that time is when these smaller record companies started leasing records from Warner Bros., Atlantic, or wherever they wanted to and re-releasing them. Because they knew they could lease the record for two years, sell the record, and make some money. So, that’s where the resurgence happened, and it kind of happened across the board with all these kinds of acts. So, I think that it wasn’t just Rough Cutt because of Rock Candy Records, I just think in general, that kind of music has had a resurgence.

I think this will happen again with 90s music. Give it five or ten years. It’s when the demographic gets old enough to where their kids are out of the house, then all of the sudden, people start going out and wanting to see this kind of music. All of this goes out of style for a while but comes back up. Eventually, the Nu Metal bands, all of those band’s kind of went out of style. But fifteen years from now, that’ll be back. It’s that curb that happens, like, “This isn’t cool anymore.” Then it becomes cool again, because the demographic aged. So, now, they’re introducing it to their kids, and they like it. It’s kind of like you; you like this kind of music, and it really was before your time.

It’s interesting. That 80s decade…was a time special because of MTV. They were making stars out of people by being on TV, and that just hasn’t happened in years. Now, we have YouTube, and it’s different; it’s more up to the consumer to find it. Whereas we were being force-fed this stuff on TV every day, many times a day. So, these people were stars. And that, I don’t think is ever going to happen again — knowing what [the band] looks like. A lot of music I like, I don’t even know what the band looks like, but I like their music. But there was a time period there where they weren’t faceless; you knew every member of the band; you knew what they looked like; if you saw them at the market, you’d recognize them. Now, that isn’t there anymore, so I think it’s a little more difficult to sell that many records. Plus, people shopped and went to stores to buy records and now, it’s just an online experience. And that’s why I think vinyl has kind of had a resurgence. It’s totally different, so I think that’s why people like you are so fascinated with that era.

Andrew:

You should see the looks I get when I tell people of my demographic that my favorite guitarists are Vito Bratta and Carlos Cavazo. [Laughs]. They look at me like I am from a different planet.

Matt:

Carlos played on three songs on this new Rough Cutt 3 record. Paul said, “Hey, I can get Carlos to play on this,” because we needed a guitar player for three songs. So, I said, “Okay, if you can, sure.” So, Carlos reaches out to me and said, “Yeah, I can do it.” So, I set up the time and I thought, “I doubt this is really gonna happen.” He was supposed to be here at noon, and he doesn’t show at noon. I’m like, “Okay, forget it.” And then he got here at 12:30. He called me, in front of my house, “Hey, I’m parked in front of your neighbor’s house. Is that okay?” Like, who asks if it’s okay to park in front of your neighbor’s house, right? I’m like, “Sure, let me help you bring your guitars and amp in.”

So, I bring his guitars and his amp in with him. I sit down; he thinks he’s only gonna play on one song. He had it kind of worked out; I heard he’d been doing a demo of it in a garage band. So, he played it, we did it, and then I go, “You got two more songs.” And he goes, “Oh, I haven’t heard the other two. I’m gonna go home and kind of figure out what I wanna do.” I’m like, “Carlos, man, what I just saw you do…you don’t need to go home and listen to these songs.” Because I’m thinking, “I’m never getting him back here again.” So, I was thinking, “I gotta get him while he’s here.” I put up the song, and [Carlos] goes, “What key is this in?” And I can’t remember the key of the song. I go, “I think it’s E.” So, he does the solo on electric one time, and I go, “Keeper!” Next song, I put up “Bleed,” he plays it. First time, I go, “I think you could do it better.” And he does it again… “Keeper!” Then we talked for an hour, and he went home. That guy is so good, that you just have to tell him the key of the song and he’s ready to go. That was it. Never heard it before.

Andrew:

I’m not surprised. That just shows the caliber of musician that Carlos is. Backtracking a bit, I wanted to talk about connecting with Simon Daniels, and the subsequent transition from Rough Cutt to Jailhouse.

Matt:

So, we were looking for a singer, because we had no singer for Rough Cutt. We were going to the clubs and checking out singers, and Jailhouse was playing at, I think it was The Whisky. One of us had been there, and came back and said, “There’s this singer who’s really good that played The Whisky last night and have a really good following, called Jailhouse.” So, we all went and checked him out; he had a cool presence about him. We approached him to join, but he was kind of in the same situation I was in when Rough Cutt asked me to join when I was in Sarge when I wanted to bring Chris along. [Simon] wouldn’t leave Mike [Raphael], and Mike was a great guitar player and had a talent for writing songs, so we thought, “Why don’t we just join Jailhouse?” So, we joined Jailhouse. We kind of meshed Amir [Derakh], Dave [Alford], and I with Mike, and Simon.

To this day, I don’t know if that was a good idea for them to do. I’m the same age as Simon, but Mike was quite a bit younger; Mike was like four or fives years younger than us. But we were a little older — I think I was twenty-six, Danny was twenty-six — but Mike was like twenty-one. I think they would have been better off without us, to be honest with you, because we were more of the Metal Pop band, and they were more of a Pop band.

Andrew:

Now, was Alive In A Mad World recorded live at The Roxy?

Matt:

So, the way we handled that record was, we recorded that live at The Roxy. Then we went into this little studio and fixed stuff that was off, or if somebody made a mistake here or there. Then we added “Stand Up,” the acoustic song. But our idea was kind of along the lines of what Guns ‘N Roses had done; I think that was our idea. So, we decided to do a live record, and that record didn’t do too bad; at the time, it’s probably more now, but it sold 27,000 copies, which was a lot for an independent record.

Andrew:

That’s Riki Rachtman’s voice at the beginning, I believe.

Matt:

Yeah, Riki’s on there. We were on Headbangers Ball all the time. I think “Modern Girl” was on Headbangers Ball quite a bit. And that video, I had done a lot of it on my Super 8 camera. And then there’s another guy, Dave Ballino, who helped us out; he had a really good editing bay; had two, three-quarter-inch machines that he could edit videos together back then and he put together that video, “Modern Girl,” that got on MTV quite a bit. But we shot a lot of that on my Super 8 camera; Tri-X film, black and white.

It was more successful than we thought it would be, but it still wasn’t enough to get the big record deal. We finally landed something at Enigma, because Restless, which [Alive In A Mad World] was on, was a subsidiary of Enigma. And Enigma, at the time, was owned by Capitol. Right when we got that deal, Capitol cut their deal with Enigma. So, then we were again left with nothing, and we didn’t end up making a record with Enigma.

Andrew:

Shortly after, your career veers in a different direction as you transition into the production side of things. How did you discover your passion?

Matt:

Well, then I had to get a job. [Laughs]. So, I was working at a medical supply company, selling stethoscopes and blood pressure kits. But I was thinking, “I wanna record my own songs,” so I bought a little ADAT, which were these VHS recorders, and a little mixer, and I was recording myself. Then I ended up getting two ADATs, so then I thought, “Maybe I could make some extra money on the weekend by recording some friends of mine.” I had some friends at work that were like a Depeche Mode kind of a band, so I’d record them.

I was in a band post-Jailhouse and it was like a 90s band. There was a drummer in the band named Scott Marcus, and his sister was married to one of the Dust Brothers, who were producing Fight Club, Beck, all that 90s stuff. They were huge. So, I said, “Look, Scott, you can bring your band in here for free. I won’t charge you if you introduce me to one of the Dust Brothers.” That was the deal. So, he did, and then I started doing a bunch of Dust Brothers stuff for Capitol Records, Dreamworks, and I did the Eels. And during this time, I was also taking some classes at UCLA, learning how to engineer. I’d had some mentors — one of them was [producer] Brad Aaron — and eventually, I kind of got hooked in and started doing the production side and sitting more in the backseat than the front seat.

Andrew:

I want to hear about the origins of your studio, MT Studios, which officially opened its doors in 1995. What was your initial vision?

Matt:

My vision was just as a hobby. [Laughs]. I mean, I was just gonna do it on weekends. I was working at the medical supply place, and the first year — 1995 — I made $40,000 in here on weekends. And I made $35,000 during the week at my job. So, I thought to myself, “If I spent more time on this, I think I could make double the money that I’m making at my job.” So, in 1997, my job came to my studio and said, “We want our credit card back,” because I wasn’t going anymore. I was not going to work. I’d only work, maybe for an hour, then leave and come home and work here. They just had enough of me, and I was forced to do this full-time. And that was scary because I didn’t know. And it’s been going ever since. My hobby turned into a job that I created.

Andrew:

That’s a great example of getting out of your proverbial comfort zone. Sometimes, that’s the best thing, because it’s essentially a sink or swim situation, and that’s where you often find out what you’re capable of.

Matt:

That’s right. And I was taking gigs I shouldn’t have taken. I mean, I was doing things I wasn’t good enough to do. I would just do anything. And during that period, there was so much music, and I knew so many people, that I was getting King Of The Hill. It was an overload of projects that I really wasn’t capable of doing, but I would just do them. Take the gig and hope for the best. And there were times, man, where I was panicking, like, “I don’t know how to do this! What am I gonna do!?”

Andrew:

As you were finding your footing on the production side, I imagine there were some early challenges. Do you have any examples of some of the proverbial roadblocks you encountered?

Matt:

Well, I’ll start with the Eels because that was my first big one; that was probably 1997 or 1998. Here I am, I’ve been doing this for maybe three of four years — two years in my studio and a couple of years before that — and I’m working with DreamWorks Records and I’m doing a record for this band that they have big hopes for. And I got that gig based purely on the drum sounds I was getting because I was pretty good at getting drum sounds right away. I don’t know how; I just had an ear for getting drum sounds. I remember the tape got stuck — I can’t remember which song it was, it might have been “Novocain For The Soul” — got stuck in the ADAT. It was eating the tape, and they were at lunch. And I was like, “Oh my God! What am I gonna do?” I’m like, “Do I cut the tape?” because I don’t know what to do. So, I take the whole ADAT apart — and this [tape] is like eaten up in there — and I’m just hoping … “Please, please,” that it’s between songs. And it happened to be before — there was a song on there that we couldn’t use the beginning of because of it. Like, we had to actually edit it in pro tools to get rid of the beginning of the song. You can imagine that clammy feeling you get, and that cold sweat, like, “I have screwed this up. This was my one-in-a-lifetime chance, and I’ve ruined it!” So, that was pretty scary.

The King Of The Hill one was pretty funny because the guy who was the music director was Roger Neill; he had a bunch of big credits; he was the composer for most of the King Of The Hill stuff. I had Gregg Bissonette in here; I was recording a whole band for King Of The Hill, and that night I was gonna mix all the cues. Roger Neill — and this was like the third day I had been working on King Of The Hill, by the way — said, “Listen, the last guy that worked on this stuff was some rocker dude who didn’t know how to think or anything. Some idiot…” He was laughing about it. Then he goes, “He couldn’t get it to sync up, and we know you’re not gonna have a problem, right?” So, at midnight [Roger] calls me — and I had been working for four hours trying to get that stuff to sync up to the picture, and I didn’t know what I was doing wrong. He calls me and goes, “How’s it going over there?” I can’t tell him because he just blasted this other rocker guy, right? So, I say, “It’s going great!” By two in the morning, I finally get it together, and I put the tapes somewhere where he can find them. He comes and picks them up, and I was sleeping. He calls me the next day and he goes, “Great job! You just missed one cue.” And I go, “Oh, okay,” and I fixed it. But he had no idea how stressed out I was.

There would just be things that I would come across that I just didn’t know how to do, and I would figure it out. The internet wasn’t the same as it is now, where you could Google it, and find out how to fix it. It was called trial and error, calling people on the phone, or whatever you could do.

Andrew:

As we fast-forward to the present day, Rough Cutt released its first video in thirty-five-years years last March, with the song “Black Rose,” a song in which your fingerprints were all over. What can you tell me about the song and your contributions?

Matt:

Basically, we had reformed Rough Cutt in 2016 with all of our sole members. Chris, Dave, and Paul were actively trying to record new songs. Wendy Dio had gotten involved again, and said, “If you guys can get more songs together, I can maybe take them to [a label].” I can’t remember. So, I wasn’t really buying into it, and I’m super busy here. And I was hearing the songs, and they weren’t very good. “Black Rose” was one of them, but it wasn’t called “Black Rose.” I don’t know what the hell it was called; it was terrible. So, I go to a Wendy Dio party, and she convinces me that she really can help us out. So, I go, “Okay, I’m going to put my time aside and do this.” This song, that was basically just a clean guitar part, and some dirty guitars in the chorus. I just sat down with it one day and wrote lyrics and melodies for the whole song, and then changed some of the stuff to fit the melodies. I played it for Chris, and he goes, “That’s amazing.” I thought the chorus I wrote was really, really good. So, we did a demo of it, and Wendy sat on it for four months, and it never went anywhere. Four songs that we had never went anywhere. She never did anything with them. I had spent my time on four songs here, and I had written lyrics and melodies to three of them. But nothing ever happened.

Then, fast-forward to April 2021, this video comes out. I was pretty shocked, to be honest with you. The old-school way of splitting up credits, when you’re in a band, you split them up equally. But when you’re not in a band, you don’t anymore. The legal way to split up a song is: fifty percent is lyrics; twenty-five is melody; twenty-five is music. So, if you are in the band, and you wrote the melody, and the lyrics, you’re supposed to get seventy-five percent of the song. I didn’t get that, and that was disappointing to me. I’m not in your band, and you took the song without my permission. You don’t do that. So, I thought, “You know what? I think I have a better version of the song. And Paul will re-sing it, we’ll get a new drummer, get Carlos Cavazo, and I’m gonna re-do the song the way I interpreted it; the way I wanted it written.” And that’s what happened.

Andrew:

Seems like you’re always get shortchanged on songwriting credits!

Matt:

Well, I’m gonna say, they didn’t give me what I should have gotten, but they gave me forty percent of the song. I should have gotten seventy-five. So, you say “You owe them twenty-five percent.” But the rest should go to the lyricist, and the rest should go to the person that wrote the melody. That’s how it should go down. Now, they changed a couple of lyrics here and there, but I didn’t give them permission to do that. And I don’t like the new lyrics, so I would have said, “No, leave my lyrics as they stand.” They changed, I think a couple of lyrics in the first verse.

Nevertheless, you get screwed out of these things, and there’s not much you can do about it. It’s kind of a free-for-all. That’s just part of the business. The way to solve this problem is before you write a song with somebody, or right after the song is written, put it down on paper right then and there.

Andrew:

Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Rough Cutt 3, featuring Paul Shortino, Amir Derakh, yourself, and of course, guest playing from Carlos Cavazo, emerges in June. It’s a killer album, I love the song “Bleed,” but how long had this album been in the works for?

Matt:

You know what’s funny? When we all decided, “Okay, let’s release some of these songs,” I had to search on my phone for some of this stuff. I had remembered “Bleed.” I remembered Paul sending that song to me in 2017. Not the song, I had played the music, and I sent the song to Paul and he sang something over it. I remembered it in my head, and I had to go back to texts in 2016. There was one thing he sent me in a text; I listened to it, and it was “Bleed.” And I go, “Oh my God, this is a good song!” So, I text Paul, I go, “Do you still have this?” He had deleted it off of his computer, so I had to rework it up and then resend it to him. And for some reason, he didn’t remember any of the lyrics — and he had sent me the lyrics back then, too — so I had them and had saved them. And I sent it back to him and he re-sang it in the studio.

Andrew:

Wow. So how long did it take to compile enough material for the album?

Matt:

Oh, fast. I mean, it took, maybe three weeks. Might have been two. When you set Paul in motion, he’s in motion. Like, he would sing the song, and send it to me. He was in his little camper — or wherever he’s in Vegas — and sending me stuff. I’d send him the music, and he would send me stuff. I would be like, “Paul, this is great. Done.” Whatever is not right, I would fix it. So, that’s how I did it. He would just send me a bunch of vocals and I would go for it. I would send it to Amir and he would do a guitar solo, and send it back to me. Then I had to mix it, and I wanted to mix it well, so I spent my time doing that. I think I spent probably four to five hours on each song. I would send it to Amir and Paul, and they would okay it, so that’s how it went down. I did it really quickly. I don’t like spinning my wheels; I like getting things done and so does Paul. So, between the two of us, that thing got done.

Andrew:

It’s amazing how quickly and efficiently everything came together. It seems the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

Matt:

We had no idea, by the way. I was thinking, “If this sells a hundred copies, I’d be surprised.” That was my attitude. But it didn’t happen like that; people liked it, which was odd. I didn’t know how good it was because we did it so fast. We just put it out there, and it kind of went viral on its own.

Andrew:

Did you catch any blowback from Chris and Dave?

Matt:

No, we didn’t get any blowback. I think the prize is having the singer, honestly. If you have the singer, that’s what people follow. The singer is the focal point of a band. If you don’t have the singer, it better be because he died or because he doesn’t wanna do it anymore. Then you gotta replace him with somebody that’s kinda on the same stature or better. In other words, the version with Paul is going to be the one people are going to follow. And I also think Amir adds a lot, too, because Amir was in Orgy, and sold a million and a half records in Orgy. So, I think that that’s another thing that gives it credibility and value.

Andrew:

Do you ever anticipate even a one-off show with the classic Rough Cutt lineup?

Matt:

No, unfortunately. We had no idea they were going to do that. I honestly believe if they didn’t do that, we would still be playing shows with all original members. But they decided that they wanted to control the name Rough Cutt, and the way they did that basically was, retiring Rough Cutt to join Rough Riot, and not letting us know that. Amir and I had no idea that they were doing that. Then they got booted from Rough Riot, and took the webpage from Rough Riot — that was from Rough Cutt, when we were all in Rough Cutt. So, the Rough Cutt Facebook got transferred from Rough Cutt, and Amir and I got removed as administrators and moved to Rough Riot. And then Paul was removed as an administrator and moved back to Rough Cutt. So, they took all that and we didn’t know. Then I found out they started Rough Cutt on Facebook. We never got kicked out, we never quit, we never did any of that. We just kind of got removed. So, you kind of think, “That’s OK. It is what it is. We’ll move on with this version, which has more credibility.”

Andrew:

As we close out, tell us what’s next on your docket, Matt?

Matt:

You do something for this long, twenty-six years, and your business changes. It moves with the times. Through that, you have recessions, you have coronavirus; all these other things that have nothing to do with music come into play. When those things happen, you change your business model. In 2008, I changed my business model from being a producer-engineer, to also composing for TV. So, I introduced a new income for myself. Then coronavirus happened, and it changed the way people were coming to record. So, I had to incorporate a remote way of recording through the internet, which was really cool. My new business model in mixing is, I don’t really have people in the studio. I’ll have a band on a Zoom, and they’re listening to me mix — if they wanna be there while I’m mixing — and they can hear it through their stereo system, through their phone, through their computer system, exactly how we’re hearing it. So now, people are actively involved in the mix, but they’re at their homes eating lunch. I’m even able to record vocals from people’s home studios, into my studio. And as things have changed and technology has changed with it, I’m not having to work as hard, because it’s easier when you don’t have a bunch of people behind you. You people who want to be there on Zoom and you have one client here. It’s drastically changed and made my life a lot easier.

As far as composing, I have a deal with this library that’s called APM Music, which is on Universal. So, I’ve put out like four or five records that are genre-related. So, I’ve put out ten songs that’ll be Country music; I did an Indie Rock one; I did a Garage Rock one; I did a Funk/Bass record; I’ve done a meditation record. I’ve done five different genres of albums that go out to TV shows, sports channels, NBC, CBS, and they pick and choose what they need from these genres. I kind of got involved in that. You can pick any genre you want, and just go with it. And it’s kind of fun for me to do genres that I’m not really familiar with, so I study them. So, that’s kind of what I’ve been doing; doing a lot of mixing; doing vocals and vocal production; producing solo artists, and composing for APM Universal.

Interested in learning more about Rough Cutt? Check out the link below:

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/