All images courtesy of Michael Kelly Smith

By Andrew DiCecco

[email protected]

Though his journey through the music industry was often hindered by roadblocks and detours, Michael Kelly Smith managed to weather the storm while continually forging ahead in steadfast pursuit of his next endeavor.

But, to fully appreciate Smith’s winding path to musical prominence, you would have to transport back over four decades, when a budding musician fueled by artistic vision and a dream moved to Philadelphia to be closer to a rapidly-evolving music scene.

The multi-faceted guitarist became a fixture within the club circuit and spent many nights showcasing his chops for a half-dozen of Philadelphia’s most promising acts. In fact, it was a rarity if Smith ever had a night off. Furthermore, as competitive as the musical landscape was at the time, he could hardly afford to.

It wasn’t until one of Smith’s bands, Telepath, needed a second guitarist that he met Tom Keifer, forming an inseparable bond that would ultimately alter the course of their respective careers.

Eventually, Smith not only convinced Keifer to shed the cover band identity to form an original band together but also to front the band. The original formation of the band also included bassist Eric Brittingham and drummer Tony Destra.

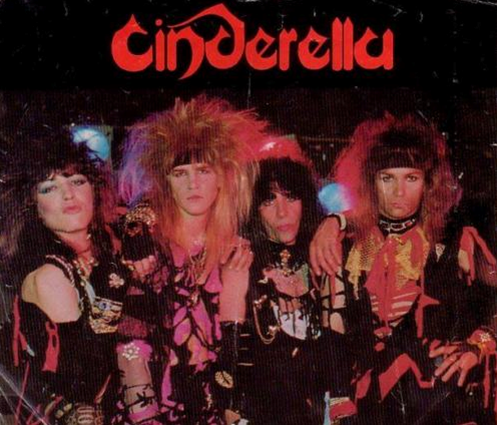

As Smith and Keifer mulled over potential band names, the name Creepshow was considered a tentative placeholder, before Smith suggested the name Cinderella. The original contingent of the band released a 7” single for “Nobody’s Fool” and “Shake Me,” and even recorded a video for the latter.

While he forever remains a crucial component of the band’s foundation, Smith was unceremoniously jettisoned from the band at the request of the record label, along with Destra.

While Keifer and Brittingham continued with Cinderella, Smith, and Destra joined forces with Dean Davidson and Billy Childs to form the initial configuration of Britny Fox.

Michael was kind enough to spend some time with me discussing his ascent through the Philadelphia music scene, the origins of Cinderella, the rise and fall of Britny Fox, his profound passion for music and teaching guitar, and much more in a rare interview.

Andrew:

What do you recall about Philadelphia’s vibrant music scene from your days as a budding musician?

Michael:

Well, it’s kind of bizarre, because I’m from Reading, Pennsylvania – well, just outside of Reading – and I moved to the Philadelphia area in order to be closer to a music scene. Back then, there was a pretty big music scene. I got into my first couple club bands, played around the whole Philly/South Jersey club and bar circuit. Eventually, I was in a band called Telepath, who had a second guitar player that left, and we auditioned guitar players. That’s when Tom Keifer came into the fold; we auditioned about 10 or 12 guys, and Tom was one of them. Ironically, the rest of the band did not want him; there were one or two other guys they liked better. I insisted that Tom was the guy, so I won that argument and got Tom in the band. We became best friends, played in numerous bands after that, and then eventually started Cinderella. So, that’s kind of the start of the original band thing happening in the Philadelphia area. We were one of the first to go out as an original band.

Andrew:

Take me through what it was like coming up through the club circuit.

Michael:

It was crazy. Way back, you used to be able to get hired at a club. You’d set your gear up on a Wednesday and play Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night and you’d play like three sets each night. So, you were there for the whole week. You were like the house band for the week and that was kind of the norm.

There were lots of gigs like that, where we would play, sometimes, three or four nights straight through at the same venue. A lot of times there were just one-off gigs, typically weekend gigs. Back then, Wednesday and Thursday nights were still a club night; people were still going out to see live music, which was beneficial for us, because that’s basically how we learned how to play. When you’re consistently playing a couple nights a week, it really helps you get a lot better.

In the summer, you’d play at the shore. There was a big club in Wildwood, NJ called The Penalty Box. The Penalty Box was the premier place to play because it was the biggest place; it had like 20 bars in it. They would book three different bands, so every night of the week, there were three different bands playing. I mean, the same three for the whole summer, but you would alternate.

At the time, I was in the band Telepath, before Tom Keifer was in the band. We would play a set at 9:00, and then the second band, Money, they played at like 10:30. Then a band called Ziggy would play, then we’d play again at midnight, then Money again and Ziggy again. We would pack the place, because the drinking age was 18, so you’d have hundreds and hundreds of people. We had lines around the place of people waiting to get in. It was awesome.

Andrew:

Your history with Tom Keifer spans over four decades, beginning with Telepath. As a founding member of Cinderella, tell us about the band’s origins.

Michael:

Tom and I had been in the Priscilla Harriet Band together. We actually took turns playing in a band called Saints in Hell; he was in, then he left, and I joined and back and forth. [Saints in Hell] was kind of a Marilyn Manson type of thing, long before Marilyn Manson; Eric [Brittingham] was the bass player.

One day I just said to [Tom], “Look, it’s really fun doing the covers, but it’s never gonna get us really anywhere other than the club scene.” Tom, at that point, was just starting to write his own material and he had some really great ideas. So, I said, “Why don’t we just start an original band?” I finally convinced him of that, and then originally, he and I were just going to be the guitar players and we were looking for a lead singer. After that failed, I convinced Tom, because in the cover bands, he would sing some Zeppelin and AC/DC stuff. He could sing it great, as you could only imagine. I convinced him to be the lead singer and guitar player.

Then, we added Eric, who was the bass player for the Priscilla Harriet Band and Saints and Hell, and Tony Destra [drums]. [Destra] was in a band called Enforcer, who I used to go see way back; they were one of the first bands to play any original music on the club scene. Back then, you couldn’t go into a club and get hired if you were an all-original band. The club owners didn’t mind if you threw in a handful of original songs in between all your cover songs, because people back then wanted to go out and hear cover music. This band Enforcer did both and were phenomenal; they were off the charts. So, I got Tony to join Cinderella.

From there, we just did demos, and started playing the Galaxy Club (Somerdale, NJ) and packing that place. We had a manger who started shopping us around, and that’s how we got the attention of record labels. All of them turned us down, not because they didn’t think we were a good band, it was because we kept being told that we sounded too much like Aerosmith, AC/DC, or a combination of the two.

Eventually, I had made a contact with Gene Simmons at the time when Ace Frehley was leaving the band, and they were considering auditioning players. I reached out to their management and got a call from Gene Simmons saying that they might be holding auditions. They were working with Vinnie Vincent at the time, writing songs, so they ultimately ended up just keeping him because he had done some studio work with them. So, I almost had an audition for KISS, but they decided to not bother. Since they were already working with Vinnie, they just decided to keep him.

Tom and I decided on the name of the band – originally, it was going to be called Creepshow – but we weren’t sure about it. Then, eventually, I just suggested Cinderella, because it was not the common name you’d ever expect a Hard Rock band to be called; it was almost a total opposite.

After we had a handful of demos, I sent them to Gene, and he loved the band. He invited us up to his apartment, we sat down, and made a plan. He said he was going to take us to PolyGram [Records], which was the label KISS was on, and help us get a record deal. So, in the meantime, right around that same period, we were pretty much the house band at the Galaxy Club.

Bon Jovi were in a studio right across the bridge in South Philly somewhere, recording their second album, 7800° Fahrenheit. After their recording sessions, they would often times come over to the Galaxy. Bon Jovi saw us at the Galaxy and loved us. So, he went back to PolyGram, and said, “There’s this band called Cinderella, you should check them out.”

PolyGram all the sudden had Gene Simmons and Bon Jovi telling them about this band that they liked called Cinderella.

Next thing you know, we had the label down to see us and that’s how that led to that deal. Unfortunately, the A&R guy who signed the band had to put his two cents in and said, “The band’s good, the songs are great — but I’m envisioning the band with a different drummer and guitar player.”

So, he said he would only sign the band if they fired Tony and I, which was ludicrous. It was beyond crazy because the band was fucking awesome; nobody touched us. Every other label had turned the band down at that point, so when the ultimatum came when PolyGram was like, “We’ll sign Tom and Eric,” but wanted a new drummer and guitar player, Tom and Eric felt that they really didn’t have a choice because there were no other options. So, Tony and I were fired.

At that point, with MTV and the image and the songs, it didn’t matter if you had a great drummer or an adequate drummer. Same with [guitarist] Jeff LaBar, who was a good player, but it just wasn’t the same.

Andrew:

Cinderella’s debut album, Night Songs, required a studio guitarist in some spots, if I’m not mistaken.

Michael:

Yeah! A guy I knew, even. A friend of mine, Barry [Bennedetta], I taught him the parts in order for him to go play them. He played on a couple things. It was fucked up.

Andrew:

Oh wow. So, after being jettisoned from a band you co-founded, named, and dedicated over four years of your life to, how difficult was it to rebound?

Michael:

Obviously, Tony and I were beside ourselves. We actually hooked up with Dean [Davidson], who was a drummer in a band called World War III, who ironically was replaced by [future Britny Fox drummer] Johnny Dee. [World War III] was a local, original heavy band, kind of more in the vein of Judas Priest. So, Dean decided he wanted to be a singer/guitar player and not a drummer anymore. Dean used to come to the Galaxy all the time and watch Cinderella, and so after Tony and I were fired, Dean approached me and said “Hey, listen, I have songs and I play guitar and sing kind of like Tom.” I had my doubts, but at that point, Tony and I had nothing going.

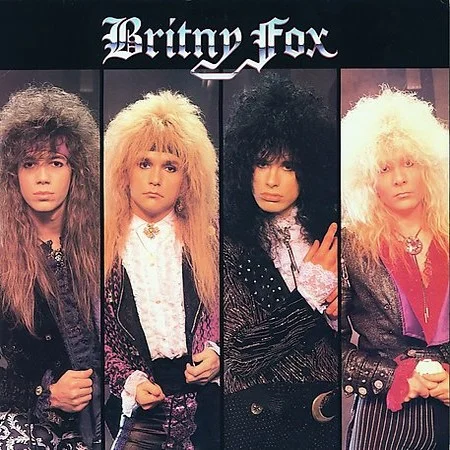

So, I got together with Dean, and sure enough, he had a handful of great riffs, song ideas – he had the riff for “Long Way to Love”, he had “Girlschool.” That’s when Tony and I got together with him. Then, we knew Bill [Childs] from the club circuit, who was by far the best bass player around. So, we got him into the picture and that was the beginning of Britny Fox.

Andrew:

How did you guys decide on the name Britny Fox?

Michael:

Dean always claimed that the name came from his family tree. He said his whole ancestry was from Wales. So, he claims he looked up this Welsh-Davidson family tree and somebody in the family was named Britny Fox. Not just Britny, but he claims somebody in his family tree’s name was Britny Fox. He was always a bullshit artist, but he was good at it. At that point, we liked the name, so we didn’t really care where it came from or where he claimed it came from. So, we just went with that story. That was his story, so we stuck with it. Although, in all honesty, we never bought it.

[Dean] had a talent for writing, was a great rhythm player, and had the charisma that you need in a lead singer. It was his idea to do the jewelry and the ruffled shirts and the long coats. The image was his idea, we went with it, and it worked. It really set us apart from all the other bands of the day that were coming up on the national scene. Certainly out of the Philadelphia area.

Andrew:

You went from climbing the proverbial mountain with Cinderella to starting from the beginning and laying the foundation with Britny Fox. What was the club circuit like for you this time around?

Michael:

Already the groundwork was laid in that whole South Jersey scene, because of Cinderella. Being that Britny Fox was now showcasing and starting out in the Galaxy Club, we packed the place immediately because everybody was interested, because this new band Britny Fox was half of Cinderella. We had instant credibility because of the Cinderella connection. So, we did demos, started shopping them around and got record interest. There was a new record label called Nemperor Records, which I believe was going to be distributed through CBS, if I remember correctly. Nemperor Records came down for a showcase and wanted to sign the band. Well, it was in February, I believe; they loved the band and said they were going to start the paperwork the following Monday morning. That was the evening that Tony was killed in a car accident.

On his way home from that showcase, he hit black ice and went into a tree; the car disintegrated, and he was killed. That was a major, major setback for us; we were on the verge of a deal. And, with Tony and I having gone through the Cinderella thing and getting screwed out of that, it was just completely devastating.

Tony was an incredible drummer and showman, had a heart of gold, and was like a brother. I miss him to this day.

Andrew:

Truly tragic, indeed. Tony was just 32 years old. As dark as those times were, you, Dean, and Bill kept the band alive. How exactly did Johnny Dee enter the picture as Tony’s replacement?

Michael:

Immediately, we thought of John, but he was in a band called Waysted at the time; he was living in Europe. After Pete Way left UFO — he ended up going back later — he had a band called Waysted, and John was their drummer. John didn’t play on their first album, he played on their second album. So, they were over there working on material, touring and doing fairly OK, not great; they were on Chrysalis Records. When we first approached John after we told him what had happened, he said he was kind of interested but would not consider it unless we had a deal on the table.

Well, Nemperor Records, that deal fell through because we didn’t have a drummer, but we continued to get interest from other labels. Luckily we knew Adam Ferraioli, who was in a band called Tangier and a friend of ours. Another phenomenal drummer. He agreed to fill in until we decided what we were really going to end up doing. We did not hire him as our permanent drummer and he was aware of that – he obviously hoped to become the permanent drummer – but we really had our sights set on getting Johnny Dee. [Johnny] did not quit Waysted immediately to join us, so we rehearsed and began doing shows with Adam.

As far as drummers are concerned, really good drummers are impossible to find. There’s a million drummers out there, and only a handful are top-notch. Tony was one of them, Adam was one of them, and Johnny was one of them. We probably had the best three drummers on the East Coast, if not the entire country. They were that good. We kept doing gigs with Adam, it was really tough getting over the loss of Tony, but Adam was such a great drummer, he just came right in and knew the songs. Then, we started setting up all the other label showcases that we could from the interest that we had. The biggest label that was interested was Columbia, but there was also Combat Records, a small indie label, mainly known for their heavier bands. They really wanted us, but we weren’t comfortable with a smaller label, because we knew that would be an uphill battle. We wanted to try to exhaust every possibility of signing to a major label.

So, Columbia Records was really interested. It turns out, Cinderella had two nights booked in Wildwood, New Jersey, at the Wildwood Convention Center. I had talked to Tom, he knew I had Britny Fox going, and I said, “We need a gig to showcase for Columbia, can we open for you guys down in Wildwood?” He said “Certainly.” We played two nights with them down there at the boardwalk and the place was packed – it held like maybe 1,500-2,000 people. Cinderella had two nights sold-out there. We played, I believe, the first night. [We] had Columbia Records come down, and they offered us a deal.

It was fortunate, because after Tony and I trying to dig our way back after the Cinderella deal went down, it was quite amazing to think I was on the verge of a record deal after I just spent all that time in Cinderella hooking that up.

So, Columbia offered us a deal and that’s when we went back to John and said, “Well, you said you’d be interested if we had a deal on the table, and we do, with Columbia Records. Are you interested?” He said, “Certainly,” came over, played with us, and the chemistry was perfect. He quit Waysted and joined us and unfortunately we had to tell Adam that we were gonna go with John. We felt bad, but [Adam] knew he was coming in as a fill-in drummer. He had hoped we would keep him, and we would have kept him if John didn’t decide to quit Waysted and join us.

Andrew:

The band’s self-titled debut album proved to be massively successful. What do you recollect from the recording process?

Michael:

The songs were so ingrained by that point because we had been playing them for two years. The band was tight and we were ready to record the album. We hired a producer, John Jansen, to produce the first album. We did what’s called pre-production – it’s like when the band goes to rehearse to record the album. We did that at a place called the Pitman Theatre in Pitman, New Jersey. We rented that for a couple days, set up all the gear, met with the producer, played through the songs, got the arrangements together, and then started recording the album.

We did the basic tracks in Philly (Warehouse Recording Studios) and then we moved to a studio in West Orange, New Jersey (House of Music) for like a month to do all the guitar overdubs. Pretty much we did the drums in Philly, maybe all of the bass, and even some of the rhythm guitar tracks. But then, we still had additional guitar tracks and all vocals to finish — and all the guitar solos — in the West Orange studio.

We had a great engineer by the name of Nelson Ayers. He never got credit for producing, but he was a great engineer and was kind of a co-producer. I never felt John Jansen really did any justice for us; he got credited as producing the album because we hired him as the producer, but it’s almost like we ended up co-producing it with him. He didn’t really add a whole lot to it, to be honest. But, you know, it is what it was.

While Columbia was getting ready to release the album, we were still doing shows. We did the “Long Way to Love” video – I remember we flew out to [Los Angeles] to do that, so we had a video for MTV after the album was finished. So, the “Long Way to Love” video hit MTV, and that was right when Poison had their second album out called Open Up and Say… Ahh! They were selling tons and tons of records, so they were just about to start their first headlining tour and were looking for an opening band. As it turns out, Bobby Dall saw our “Long Way to Love” video and loved the band and said, “These guys should open for us.” We got the call from their management that they wanted us to open on their headlining tour; obviously we were elated and were like, “Fuck, yeah!” That’s the exposure we needed. The label was great; they were into it and gave us the tour support we needed, because it cost a lot to go on a major tour like that.

You actually don’t get paid much at all from the headlining band; it’s almost like they’re doing you the favor of just having you on the bill. They’re paying you like, I don’t know, $700 a night. It was ridiculous. You could never sustain on that, so the label was giving us $5,000 a week to be able to do the tour, because they knew it was gonna pay off. If you’re on a tour like that, playing in front of those large audiences, you’re gonna sell a lot of records. So, that’s why it’s in [the label’s] best interest to give you that tour support, which, by the way, is recoupable. The investment was mostly beneficial to them; I mean, it was good for us as well, but not monetarily.

Yeah, we ended up selling a ton of records, but we didn’t make any money, because all the money had to be paid back to the label for the tour support and the videos; the videos cost a fortune to make. In fact, our first album cost $80,000 to make and that was our budget. We spent every dime, so we didn’t even make money off of that. Our record deal was for $80,000, and we spent every dime to make the album, which was considered cheap for even back then. We were able to do it because the band was tight and the songs were so well-rehearsed. We didn’t have to dick around; we went in and just recorded the songs.

The label, in the beginning, was very supportive. We went on that Poison tour, the album went gold in a couple months, selling over half a million records. After the Poison tour, we did a run with Joan Jett, then we did a couple months opening for Ratt who were supporting their Reach for the Sky album on the City to City Tour, then we went back and did another run with Joan Jett. Also, in between, we did a lot of one-off shows, playing small clubs and theaters on our own. At this point, the “Girlschool” video was a hit and our third video, “Save the Weak”, was also doing well on MTV. We also had a song called “Livin’ on the Edge,” which was a Japanese bonus track and also appeared on the Iron Eagle II soundtrack. We were really rollin’ at that point.

Andrew:

The band essentially caught the final wave of the 80s with Boys in Heat (1989). Despite the sudden shift in musical landscape, the album did relatively well, all things considered.

Michael:

It was fortunate that we did, but unfortunately, we caught the tail-end of the whole Hair Metal thing. By the time Boys in Heat was released, it was already starting to fade, simply because of the oversaturation of all the crap bands that were signed under the guise of Hair Metal or Glam Metal. The labels were just signing every band off the Sunset Strip in L.A. and it was getting ugly.

-format(jpeg)-mode_rgb()-quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1962800-1515277452-9451.jpeg.jpg)

Andrew:

Dean remains a polarizing figure in Britny Fox lore. Tell us about his dynamic within the band.

Michael:

Dean wasn’t thrilled that Tony and I got a lot of attention because we were in Cinderella. It’s what got our foot in the door and ultimately what got us signed. I’m not saying that Britny Fox, if it had nothing to do with Cinderella, wouldn’t have gotten a record deal. But I’ll tell you this, it made it a lot easier, because we sounded similar to Cinderella, we were from the same area, and we had two original members. Dean wanted it to be all about him, being the main songwriter and the lead singer, and I get that. But, instead of being thankful for the Cinderella affiliation, he seemed to resent it at times.

We ended 1988 opening for Bon Jovi in Tokyo, Japan. We played in the Tokyo Dome, New Years Eve, in front of almost 50,000 people – and it was televised; there were cameras on cranes everywhere. We were told there were probably two million people watching it. It was us, a band called Kingdom Come, Ratt, and then Bon Jovi. It was the biggest gig we ever did, obviously. We were starting to sell a lot of records in Japan and things were really really coming together. That was our peak.

We came back from that, had most of the material for Boys in Heat, and recorded the album. We did the album entirely in New York. We moved up there for four months, rented an apartment, did pre-production up there, did all the tracks, and overdubs, and mixed it all with producer Neil Kernon. [Boys in Heat] was a great album; different than the first, because it had a much better production quality to it but it was still heavy at the same time. The main mistake we made with that album, was too many songs; we should have done maybe 11 or 12.

As we were recording the album, Dean and I wrote: “Dream On,” which also became a hit on MTV, in addition to the “Standing in the Shadows” video. We wrote it while we were in New York after we had already started recording the album, but we thought it was such a strong song, we decided to include it. But, instead of dropping a song, we just added it. By the time you put an album on and you get to the end of it, it was just too long. That was starting to become the thing with Def Leppard and stuff, but for us, it just didn’t work. Not only for that reason, but it also cost us a lot of money. We went overbudget, we spent more than the label budgeted for that album – which put us further in debt. That was a bad mistake from a money standpoint, but it was also a mistake artistically.

We finished Boys in Heat, and at that point, we had not been out of the country — except for that Japan gig — but we never toured outside of the US. We knew we needed to get over to Europe to get exposure to try to get more of a foothold there and sell more records. We were offered Alice Cooper’s Trash Tour in Europe. We were labelmates, too; [Alice Cooper] was on Epic, part of Columbia Records, and we were on Columbia. We couldn’t ask for more than that. It was us and Alice Cooper for the first two months, and Great White was added to the bill for the remainder of the tour. We played all of Europe; the tour was phenomenal. All said, things were going great.

While we were over [in Europe], we got signed on to do the KISS tour in the US, which was the Hot in the Shade Tour. Gene, obviously, was a Britny Fox fan and Paul liked the band a lot, too. We signed on to do the tour as the scheduled opening act, which was supposed to start in February or March of ’90. Then, because of slow initial sales, they decided to push the tour back a month or two in order to try to get momentum with radio and MTV. When we got word, we thought, “No problem. We’ll book a bunch of shows on our own after we get back from Europe,” because, at that point, we were riding pretty high.

In the interim, Slaughter released their first album, which went through the roof. It turned out that their manager had a close buddy at MTV and was able to get Slaughter videos into heavy rotation, which helped the album explode. Their album was outselling our album. Gene and Paul saw what was happening and decided that they needed a stronger opening act from a business standpoint, so we were told that Slaughter was going to replace us.

At that point, Dean got very disenchanted, because I think he thought our big break was gonna be that KISS tour. It certainly would have been a game-changer; I’m sure Boys in Heat would have went gold, and the first album would have gone platinum because of it. The first album did go gold and was just shy of platinum. But, had we been on that KISS tour, we would have been on our way.

Dean couldn’t handle the fact that we got bumped off the KISS tour. But, what he failed to realize, is that because of it, our booking agent was able to book us on a headlining tour of smaller venues. So, we had six months booked of the highest-paid gigs we ever had done. We would have, for once, started to make a little money. But, Dean obviously wasn’t looking at the bigger picture, in that it put us in the position to go out and headline smaller venues, make a ton of money, and still have the opportunity to get onto another big tour. In 1990, there still was gonna be another big tour that we could have gotten onto, I’m sure.

At the time, the Black Crowes were out and they were a big thing. So, Dean decided that he wanted us to be more like the Black Crowes – and this even started when we recorded Boys in Heat. He went through his little Def Leppard phase, too. He wanted to incorporate Def Leppard-style vocals on the Boys in Heat album. We’re like, “Let Def Leppard be Def Leppard and we should keep doing what we do.” You’re always going to slightly change your style a little bit here and there, but you don’t go from one extreme to another. [Dean] wasn’t happy that we didn’t want to jump on the Def Leppard bandwagon. The Black Crowes aren’t going to wake up one day and decide they wanna sound like Britny Fox, so why should we wake up one day and decide we wanna sound like the Black Crowes?

Dean decided, “Fuck this,” he’s done with it and decided to quit, which was really lame and it left us fucked royally. We had six months of great-paying gigs lined up, and we had no singer. The band was done. You lose your lead singer, you’re done, at least for the time being. So, the label decided to keep us on, thinking we might be able to get a replacement singer for Dean within 4-5 months. Well, it took us a year; we auditioned tons and tons of singers because nobody was right until we found Tommy [Paris].

Unfortunately, by then, the label had given up hope and dropped us. So, we went from having a label and no singer, to finding a singer and not having a label. We were back to square one again: completely broke. It was the point of no return.

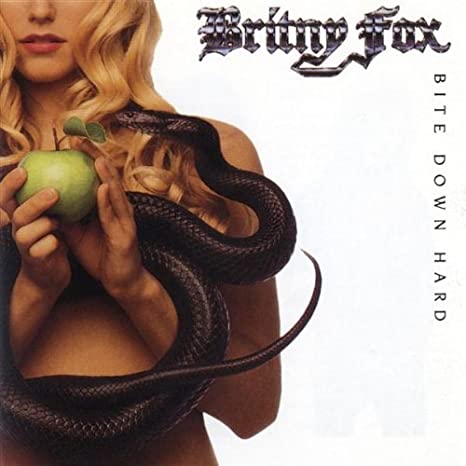

Even though we found Tommy, who is a great singer, we were just at that verge where, had Dean not quit the band, we would have gotten another year or two with him. The fact that it took us so long to find Tommy, Columbia dropped us, so by that time, we had to start from scratch. We had to write songs, do demos, and shop for another deal. We finally landed at EastWest Records, which was part of Atlantic.

Then, we went out to L.A. to record the Bite Down Hard album and it came out in 1991. Well, guess what? By 1991, Glam and Hair Metal was dead. It was over. So, we were dead in the water; the album came out and did nothing. We toured for that album in a van – we were long past the days of the tour bus, tour support, and all that stuff. We had decent crowds, and the people who knew about the new album with Tommy really did like it, but we could never recapture the whole vibe we had with Dean.

Andrew:

Clearly, the band was navigating through a transitional period. However, you guys managed to endure and release Bite Down Hard, which was a unique album in many ways. For example, you had Zakk Wylde play a solo on the opening track, “Six Guns Loaded.” How did that come to be?

Michael:

We went out to L.A. to do the Bite Down Hard album. Our producers were Duane Baron and John Purdell; they were just finishing up doing the Ozzy [Osbourne] album, No More Tears, and obviously, Zakk was his guitar player at the time. The studio was called One On One Studios; the album before No More Tears that was recorded there was the Metallica Black Album. When we got out there, we did pre-production and were ready to start recording, but the Ozzy album ran over; they weren’t happy with the mixes. So, we had to wait a couple of weeks until Ozzy was finished — obviously, they aren’t going to kick Ozzy Osbourne out of the studio. They told us we could still come in and do the album, but we had to wait until Ozzy was done. But, Ozzy was cool enough to invite us in to hang around and even set up our gear, because they were finished recording and were just mixing. So, we got to hang around for the whole second mix of the album.

We knew Zakk from before, and we got to hang out even more while this whole process was going on. The Ozzy thing finally got completed and they moved out of there and we started recording the album. But Zakk, I guess, had nothing to do, so he was still hanging around. He really liked “Six Guns Loaded”, so I’m like, “Hey, man, you’re welcome to play on it if you want.” He’s like, “Fuck, yeah. Cool.” So, we had the rhythm tracks done, and at that point, I was already starting to do some solos. I did the first solo and then I offered Zakk, “Hey, if you wanna take the whole last solo, go ahead.” So, he plugs in – he’s got his Les Paul, the whole deal – and away he went. And in like three takes or something, he did that whole solo at the end. It was cool. Then, of course, I had to learn it to play it live. Live, I would kind of copy his solo that he did on that. Trying to keep up with him is hard to do, let me tell ya.

Andrew:

The 80s were a proving ground for shred guitarists. Did you ever feel compelled to alter your playing style to coincide with the times?

Michael:

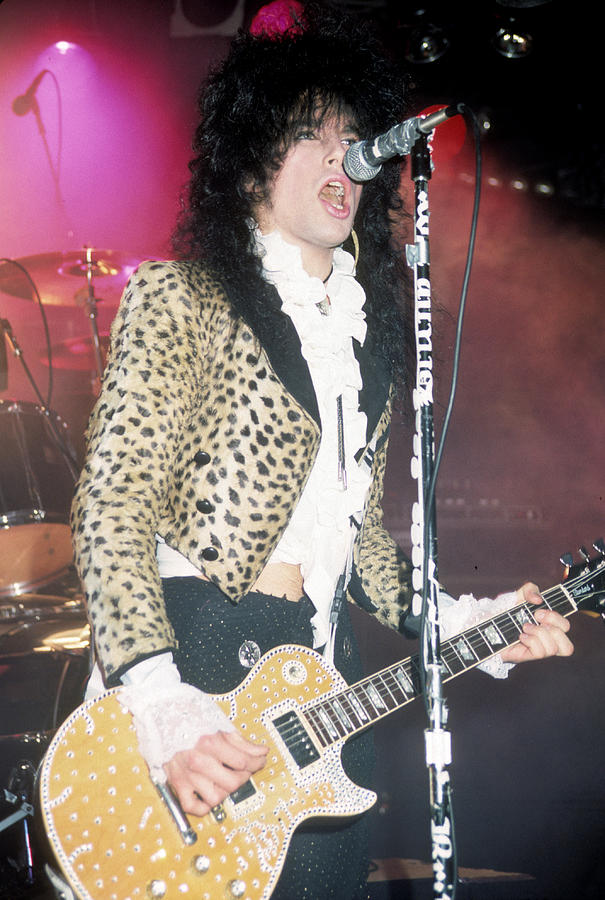

No, not at all. I grew up in the 70s, so my whole vibe was more of an Ace Frehley, Ronnie Montrose style of playing. Yeah, [Eddie] Van Halen was the late 70s and I learned how to play that stuff, but it wasn’t really part of my style. My main influence was Michael Schenker from UFO.

I always kind of just did what I did. At that point, I had developed my style. I never really thought of myself as part of that whole guitar shredder group of players. That style never appealed to me. I mean, yeah, I could play fast here and there when I thought it fit, but it wasn’t my thing. In fact, I wasn’t really a fan of it. My goal was to play more like Schenker — more melodic. But, don’t get me wrong, I completely respect and appreciate what those guys can do.

Another thing, for me, so many of those players, you could not tell one from the other. I was always trying to approach it more from, I wanted to have my own style and sound — which is hard to do — but I think I accomplished it to a point to where I didn’t sound like those guys. I might not have sounded as unique as a Ronnie Montrose or a Jimmy Page, but I kind of took those influences and created my own style.

Andrew:

I want to ask you about the disbanding of Britny Fox in 1992. Would you attribute that to the whole Grunge scene or the inner turmoil within the band?

Michael:

The chemistry was there with Tommy, but not the same chemistry we had originally. So much of what we had with Dean was completely lost after he left. For example, the look of the band – we were very image-oriented with Dean. Of course, on Boys in Heat, we even toned down the image a little bit; it wasn’t quite so over-the-top as it was on the first album. The first album wasn’t as over-the-top as Poison on Look What the Cat Dragged In. We weren’t that Glam, but we were certainly more Glam than we we ended up being on Boys in Heat. We thought, “Well, maybe we’ll just tone this down a little bit and we actually might get taken a little bit more seriously,” because of the onslaught of the overkill of all these bands being signed that really sucked. We thought we could disassociate with that a little bit, but we didn’t lose the inherent image of the band.

When Tommy came in, because Seattle and Grunge was the thing, there was a pretty huge backlash against Glam and Hair Metal. We had no image aside from the hair. We no longer did the choreography on stage; we no longer tried to have a cohesive look as far as the clothes. That, to me, was really a disheartening thing because we lost the essence of the band. Between that, and the fact that the whole Glam Metal scene was over, we went out and toured and could not break even. It just wasn’t worth doing anymore. We couldn’t do it, even if we wanted to, because we couldn’t afford to go out and lose money.

Andrew:

After disbanding, you managed to remain largely out of the public eye for nearly a decade. How did you spend the idle time?

Michael:

After the break in ’92 with the Bite Down Hard thing, I still wanted to keep writing and playing, so I put the band Razmanaz together. We actually started to get airplay at XM radio at the time; somebody there got ahold of the CD and was playing it and it was getting an insane response. They said the phones, back then people would still call in to request a band, were just getting inundated with requests to play that new band Razmanaz. So, we got great feedback from listeners, and people who were hearing it on XM radio; the problem was, it was on Perris Records and it had almost zero distribution, so nobody could buy it! We had thousands of people that loved it and would probably search around trying to buy it somewhere, but they couldn’t; it wasn’t in a store or anything. Some people tracked it down and bought it on Perris Records’ website, but you’re only talking about a couple hundred here and there. It’s not gonna add up to anything.

So, I did Razmanaz and started teaching guitar, which I had done on and off through the years. That’s also when my wife and I decided to expand our cat rescue efforts to include off-the-track Thoroughbreds, whom, in addition to our dogs, have become part of the family. So, most of my time back then was devoted to teaching and animals.

Andrew:

Given that you all seemingly went your separate ways in 1992, the odds of a Britny Fox reunion appeared increasingly slim as the years elapsed. However, the Bite Down Hard lineup was ultimately reformed in 2000. Tell us more.

Michael:

Johnny Dee ran into Paul Bibeau, the [founder] of Spitfire Records, and they got to talking. He said, “Hey, is Britny Fox ever going to do anything again?” John said, “Maybe, but maybe not. Probably not.” He said, “Well, if you guys wanna consider doing a live album, let me know.” So, John, after meeting with this guy, called us and said, “Hey, we have a chance to do some live shows, record them, and put out a live album.” The time was right, so we did. We got together, rehearsed, booked a bunch of shows, and went out and played. We ended up recording two or three nights of shows, then we edited down and that’s what became the Long Way to Live! album. And, because it did fairly well for a small label, they then extended the deal to do another studio album. After that, is when we did Springhead Motorshark.

Andrew:

The Bite Down Hard quartet collaborated for another studio album 12 years later, entitled Springhead Motorshark. If you could, share the backstory for those unfamiliar with the album.

Michael:

From a strictly musical standpoint, Springhead Motorshark showed the depth of what we had to offer, in that we went into it with the attitude of no guardrails. Like, we weren’t trying to sound like the first two albums, we weren’t trying to sound like the Bite Down Hard album, we just went into it completely fresh; whatever ideas we had, is what we went with. As it turned out, we were probably competent enough that you never would have dreamt what we came up with. We were able to hit on so many different levels of musical styles and sounds. This one song on there, the opening track, called “Pain”, it’s as heavy as you can get. It’s the heaviest thing we’ve ever done, without a doubt. Then it also has a song called, “Is it Real?,” which is almost like an acoustic thing that you’d hear around a campfire. The album’s kind of all over the place, yet, it all fits together perfectly.

By the way, we recorded it in a basement with our own recording gear; it was done super low budget. Tommy and I produced it, so we spent hours and hours and hours trying to get a big studio sound out of $10,000 worth of home recording equipment. It was crazy, but we pulled it off. So, it’s a decently produced album, but the music on it, for me, I’m most proud of how we were able to diversify more than anybody ever thought we could. As diverse as it is, it has this weird common thread through the whole thing, almost like a concept album. One song leads to the next, and it ebbs and flows beautifully.

Andrew:

After years of miring in relative obscurity, Dean resurfaces in 2010 and attempts to reform Britny Fox with the classic lineup. Dean’s exit essentially sent the band in a tailspin in 1990, so how was his sales pitch received?

Michael:

He wasn’t totally up front about it, but he called me, and at that point, I was still not past the grief that he caused. Not that I ever really held a grudge, but he really did fuck us over. For him, it wasn’t so bad, because when he quit Britny Fox, he just quit a band that was flying pretty high. And he was able to go do Blackeyed Susan, which was signed to PolyGram Records, and he allegedly got a huge advance for that album. He was the singer from Britny Fox with his new band, so of course, a label was going to throw money at that. When he quit the band, we were broke and unemployed.

So, that pissed me off really bad for a long time. But, after all the years had passed, he called up and I was civil. He was like, “Hey, you know, I might have some interest.” Well, he claimed he did have label interest if we were willing to put the original band back together. So, even though I wasn’t holding a grudge at that point in time, I was like, “Nah, no thanks. I’m not interested.” He had John and Bill pretty much on board. I know John for sure, was interested in trying to revive the original lineup. But, I had other stuff going on and just couldn’t bring myself to get involved with Dean again after what he had pulled. I was like, “Ya know, I have to draw the line somewhere.”

His vibe was not apologetic; it was almost like, if we regroup with him, he’s doing us a favor by coming back to us. Put it this way: we knew we needed each other; he didn’t know that. He thought we were disposable.

We had so much more to offer with Dean in the band, had we just been able to finish out the next couple of years. We could have made it into the early 90s had we just stayed true to ourselves, had the original lineup, and all that. But, coming back with a new singer, with a new label — during [the rise of] Nirvana and Pearl Jam — it was a done deal. It was a lot of hard work with nothing to show for it.

It’s really a shame that we didn’t hold it all together. The original lineup had the talent, chemistry, image, and determination that few bands had. Sometimes, it’s hard to believe that we let all of that go down the drain.

Andrew:

The band reformed in 2015 with three of the four members of the Bite Down Hard album. How did the initial conversations go and what prompted you to decline?

Michael:

Well, they went out multiple times with different lineups. The first time they went out, they were a couple weeks into the tour, and their manager was calling me three times a day saying, “We need you back in the band. This isn’t working.” I was like, “Well, I could have told you that.” I did give my blessings initially, when Tommy, Bill, and John wanted to go out, and I just said, “I can’t afford to do it. I have a life, I have bills, I have responsibilities. Even if I wanted to, I couldn’t do it. But, I certainly can’t do it and not make any money.”

So, I said, look, “If you guys get a competent, decent guitar player that fits the band, go ahead and do it.” I was OK with them trying to go out as Britny Fox with a competent guitar player. I didn’t want them hiring just anyone. Well, they ended up doing exactly that. In fact, they started out with a rhythm guitar player from a band called Gunshy, who I produced a record for. So, I knew the guy who that they got and he was a good rhythm player, nice enough guy, but was not a lead player. I’m like, “What the fuck?”

Andrew:

With many of your contemporaries reuniting, is it safe to assume you have zero interest in reviving Britny Fox with the original lineup?

Michael:

I mean, I have considered, before COVID, the possibility of the original lineup doing a couple Philly shows. Not even trying to go out and do some nostalgic tour or one of those Rock cruise tours where it’s all about nostalgia. Which, I get, but I’m not interested in it. But I did consider the possibility of doing some Philly shows, because of course that would be our biggest audience, with the original lineup. So, I will go as far as that. Not that anybody came to me with that idea, but I actually thought to myself, “Hey, that’s something I might consider and could be cool.”

Andrew:

Looking back on your time with the band, particularly in its hay day, how do you remember that moment in time?

Michael:

Oh, it was the best. It was the greatest. Deep down, you kind of get a sense of where you might end up, even if things all go well. I always was more of a realist and thinking we’re probably not gonna ever end up being an Aerosmith or a KISS, but I thought we could hang in there and be a band that could have had a couple of albums that really meant something. I knew we had the potential to end up being more successful and having more longevity than we did. But, looking back, I’m very proud of what we did accomplish all throughout – even with Tommy, because it was amazing that we were even able to pull that off. But I’m most proud of the early years and the success that we had.

[MTV] had a show called Mouth to Mouth, and they would have “Bands of the Day” in the 88-89 era of that time period, where they would have bands come on, do an interview, and then play a couple of songs live in front of a very small studio audience. We were on that show; we did “Girlschool” and “Long Way to Love.” We were at our peak – we still had the image, the clothes, the hair, the jewelry, the makeup, the choreography. I mean, that was what the band was all about. Anything past that, especially after Dean left the band, to me, was never quite the same again.

Andrew:

In addition to your animal rescue efforts, you also mentioned that you teach guitar full-time. Tell us more about that.

Michael:

Off and on, I always taught whenever I could, because I really enjoy it. I like being able to teach and turn younger players onto, not only 80s music but even the 70s stuff that I grew up with. Which I actually find that most of them are more intrigued with that, believe it or not. I mean, a lot of new students will come to me and they’re like, “We want to learn Britny Fox songs,” which I teach them. But, because of their age, they’re not aware of what influenced Cinderella and Britny Fox, so I actually turn them onto Slade, Foghat, Nazareth, UFO, Scorpions, Aerosmith, Sweet, whatever; stuff they’re not necessarily familiar with. Really, that seemed to be the most intriguing thing for them, that I’m able to open up the door to introduce them to all the stuff I grew up with. That, to me, is still the best music ever.

Andrew:

How can people who have an interest reach out?

Michael:

I’m still new to Facebook, so it’s still all new territory for me. I’ve always taught on and off forever. I taught for a good 10-15 year-long stretch of in-person lessons, prior to COVID, at different music stores. Since COVID, I’m obviously only doing virtual lessons, but I’m still in the beginning stages. Anybody interested in lessons can message me through my Facebook page for more information.

That’s kind of my thing now. I’m a good teacher because I’ve done it for so long and I have a vast catalog of songs and knowledge of guitar playing and music.

What I find at this point in my life, is nothing is really cooler — I have much more of an interest now of passing the torch, so to speak, and helping younger people learn how to play and turn them onto the music that I grew up with and all the great stuff since. My passion lies more in that area now than it would be trying to reform the band and pretend it’s 1988 all over again.

Andrew:

What’s next on the horizon for you?

Michael:

The first two albums, ironically, are being re-released again on a UK label [Rock Candy Records]. Dave Reynolds, who was a writer for Kerrang! back in the 80s and early 90s is doing all the liner notes for them. I’m looking forward to their release and seeing what kind of impact it will have. I just spoke with Dave Reynolds the writer, and he talked to John and Bill as well; he could not get ahold of Dean. He wanted to get a whole new perspective looking back on those first two albums so that he could include a new essay as part of the reissues.

I’m really looking forward to expanding my lesson profile, getting more students on board, and sharing all this stuff with them. I have like 14-15-year-old kids learning Britny Fox songs, solos, and everything. I have them playing Darkness songs; I have them playing the entire Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin catalogs. I turn them onto this stuff and they lose their minds. They can’t even believe that this stuff ever existed.

It’s such a great thing to be able to share that with the new generation of people who are interested in rock music and especially in playing guitar. It doesn’t take them long to fully understand and see the connection once I start teaching them this stuff. Of course, I have a handful of students that are beginners, but once I get them through the beginner stage, they start getting to the point of being able to play songs and become aware of this great music that’s out there. They’re like, “Wow, I wanna learn another Aerosmith song. I wanna learn another UFO or Foghat song.” It’s really fulfilling; it’s really awesome.

As daunting as the journey appeared throughout his career, Smith never lost sight of what he set out to accomplish over four decades ago.

Sure, Britny Fox never did reach the heights of some of their more heralded contemporaries, but the band held on long enough to leave their stamp on one of the most iconic eras in music history.

“I was glad to come back after [Cinderella] and at least do something in the music business and make a lasting contribution,” Smith remarked.

– Andrew DiCecco (@ADiCeccoNFL) is the Senior Editor for vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at [email protected].

Really in depth and honest interview. Enjoyed it – and the video!

I was so sad when it was over! I wanted to listen to Michael speak for hours! So glad you enjoyed it too! Thanks for popping by, and stay safe!

Great interview! Having grown up in Delco, I love reading about the musicians and bands that made the scene back in the day. Michael’s candidness about the ups and downs of being a rock star was fascinating. I’ve been playing drums and listening to heavy music for the last 40 years. I’ve been fortunate to have found a couple of great musicians that share the same passion, sense of humor and musical chemistry. (One of whom, sent me the link to your interview) Reading it reminded me of how much I’ve missed playing over the past year. Can’t wait for things to to return to normal. Thanks again for a great read. Cheers!

I couldn’t agree more that Michael gave an outstanding interview here. What a storyteller! So glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for popping by, and stay safe!

Thanks for reading, Tom! Michael is a first-class person AND storyteller. An absolute pleasure to talk to. Check out the “Shake Me” demo and “Mouth to Mouth” performance that Michael mentions here, on YouTube. He sounded just as sharp playing live as he did on the records.

I used to tech for Michael. It was really great to read this and hear what his been up to. Great interview!

Get out! For what tour? I appreciate you dropping a line, Don. Glad you enjoyed the interview.

Boys in Heat. The beginning of the end.

Boys in Heat tour.

Boys in Heat!

Very cool, Don! I was actually spinning Boys in Heat just the other day. I’m sure you have plenty of stories from that!

The Alice Cooper Europe tour was great. And like Mike, I was so looking orward to the KISS. Bummer it didn’t happen.

Andrew: Great interview…valid questions and honest replies from Michael.

I have all the discography from Britny Fox..Michael Kelly Smith in my opinion is a badass guitarist. If I could only be a student of his for one year, it would be awesome. As soon as Rock Candy Records releases the reissues, I will get them for the bonuses and remastering.

Britny Fox remains in my playlist….

Alex

Alex, thank you! I appreciate the kind words. Yes, Michael was an absolute pleasure to talk to. Amazing guitarist and an even better person. I’m glad there is an appreciation for his musicianship and Britny Fox. Drop him a line if you’re interested in taking lessons, or I can reach out on your behalf.

Amazing interview! What a history. Michael is extremely talented and just the nicest guy. He’s got more music knowledge than anyone I know. I was lucky enough to have him as a guitar instructor and loved the lessons!

Thank you, Taylor! Michael is an incredibly talented guitarist and even better person. I haven’t met anyone as well-versed in music knowledge as MKS! He has already put me on to music I wasn’t previously privy to. I appreciate you reading and taking the to comment. Feel free to share this with as many people as possible!

Great interview! The first Britny Fox album was awesome when it came out and still is today. It will always be on my playlist. I always thought Michael was an amazing and very underrated guitar player. It was cool to see where he’s at today. Thank you

Rick, thank YOU. Truly. I appreciate you giving it a read. I had a long car ride over the holiday and gave the first album a listen twice and also gave Boys in Heat a listen. Michael is an incredible guitarist, and an even better person.

Awesome interview. Exactly how a rock band should’ve sounded and looked for that period. I have many happy memories of touring with these guys back then.

Dave, thanks so much! Honored to see this feedback. I am incredibly proud of the finished product. Hopefully, the music and story of Britny Fox reaches a new generation.

Hi Mike!!! Great interview and I find it very interesting that you have a race horse rescue. I’m interested in hearing more about that. And apologize for up and leaving suddenly in the 80s.