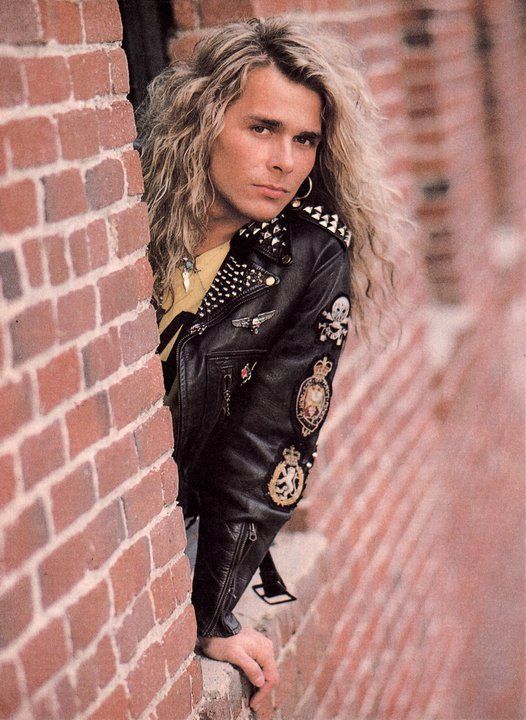

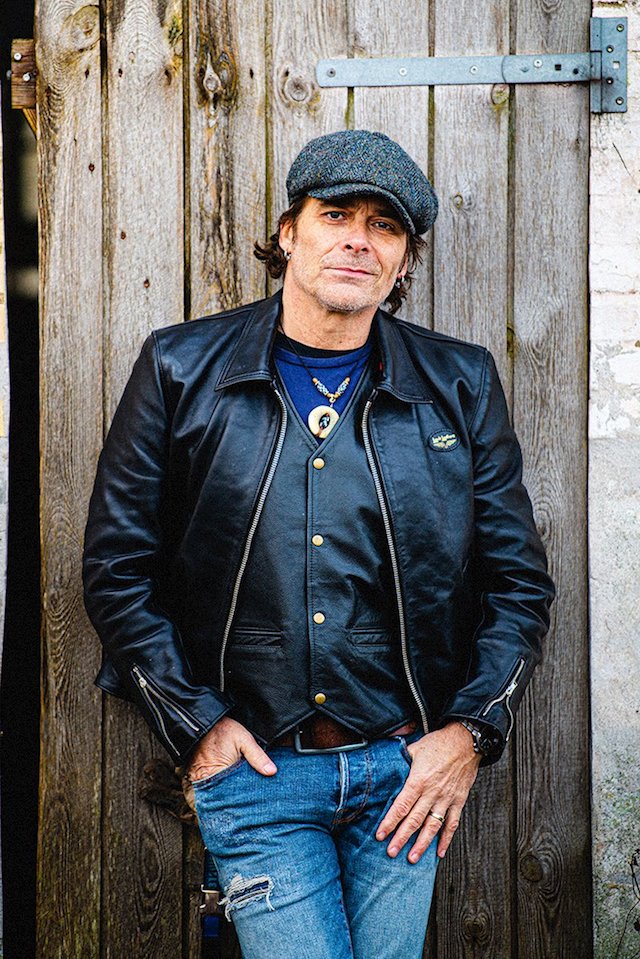

All images courtesy of Mike Tramp

Mike Tramp put pen to paper on a lifetime contract to Rock ‘N’ Roll nearly five decades ago.

Tramp, a native of Copenhagen, Denmark, first arrived in New York City in 1982 with his band Lion, intent on fulfilling his dream of becoming a rock star. After experiencing a brief taste of the New York music scene, the cash-strapped band returned home to Denmark. However, the taste was enough to hasten the trajectory for the ever-determined Tramp. Within months, Tramp, along with some help from his mother, would eventually gather enough money to return to New York.

Upon returning to the Big Apple in 1983, Tramp was incidentally handed a phone number that led him to a fast-rising Staten Island guitarist named Vito Bratta. The creative minds, fueled by a similar vision, desire, and commitment, formed an instant connection. Tramp and Bratta, along with bassist Felix Robinson and drummer Nicky Capozzi, formed the initial incarnation of White Lion.

Forged in a spacious rehearsal room underneath the stage of L’Amour, a music venue in Brooklyn, New York, Tramp and Bratta would tirelessly prepare for the arena days. The band’s debut album, Fight to Survive, never gained the traction it warranted, but due in large part to Tramp and Bratta’s resilience and fortitude, White Lion managed to weather the storm. The inaugural lineup would not stand the test of time, however, as Robinson and Capozzi were ultimately replaced with bassist Dave Spitz and drummer Greg D’Angelo, respectively. Spitz would eventually jump ship in favor of another project and was replaced by James LoMenzo, who proved to be the final piece to the classic configuration of White Lion.

Signed to Atlantic Records in 1987, the newly-formed quartet rewarded the record label with a timely rebound, achieving double platinum success with their follow-up album, Pride. The album, which included the MTV mega-hit “Wait,” vaulted the band to new heights.

Despite the newfound success, White Lion was rarely afforded a moment to appreciate the arduous climb toward validation. With MTV serving as a primary catalyst to the band’s success, their faces were soon plastered across the most prominent magazines of the day. Tramp and Bratta, in particular, were suddenly household names.

The ever-vibrant Tramp had evolved into perhaps the most recognizable name in Rock in both name and appearance by the late 1980s. His charisma, attitude, and infectious energy rendered him the de facto leader of the band.

Bratta, far more reserved by nature, was a virtuoso talent whose fiery riffs are most associated with the band to this day. The Staten Island native, revered for his rare blend of technical command, structure, and shrewd sense of melody, graced the cover of many distinguished guitar-centric magazines, including Guitar World Magazine in Sept. 1989.

A dynamic and tight rhythm section, which included the controlled aggressiveness and natural stage presence of bassist James LoMenzo coupled with the monstrous drum fills and precision timing of Greg D’Angelo, proved to be essential to the band’s sound.

Following the roaring success of Pride, White Lion notably served as support acts on Aerosmith’s Permanent Vacation Tour, AC/DC’s Blow Up Your Video Tour and Ozzy Osbourne’s No Rest for the Wicked Tour. However, the taste of success would prove to be all-too-brief for White Lion, as the band would produce just two more albums before disbanding on Sept. 2, 1991.

These days, whenever Mike Tramp reflects on his former life as an 80s rocker, he’s able to do so candidly and with a clear-eyed perspective. I recently sat down with Mike to discuss his lionized career in music.

Andrew:

I appreciate you making some time, Mike. I’d first like to hear about your musical roots growing up in Copenhagen, so talk about your earliest introduction to music.

Mike:

I grew up with the acoustic guitar in the corner. I come from a divorced family and two brothers; a little apartment in Copenhagen; never had a car, never had a shower in our apartment. My mom replaced the alarm clock with a turntable, so we got woken to Johnny Cash, and [Bob] Dylan, and Elvis Presley, and Roy Orbison. That’s how we got the day started before we entered school. So, that form of Folk music – the straight-ahead strum – it sort of just became the root and the foundation to the music in our house. We’re not a musical family; we’re just a family who loves music. Little by little, one day, an acoustic guitar appeared in our apartment, and me and my two brothers would jingle and jangle on it. It would be the early foundation of how I start my songwriting. It really has never changed.

I grew up in the 60s, and American Folk music and that kind of thing was very big in Denmark because a lot of the local artists and fans of music were able to play “Blowin’ in the Wind” and those kinds of songs. It’s a little more difficult to sit on a bench with an acoustic guitar, playing Emerson, Lake, and Palmer. Overall, Folk music is a big, big foundation of Danish music, so it was always with me. And then when I got into my first band, we were a middle-of-the-road Rock ‘N’ Roll band, leaning towards mid-70s British Rock – Sweet, Slade, Queen, Status Quo, etc. Then bit by bit, by 1980-1981, we were living in Spain; we had moved to Madrid, Spain. I was only 15-and-a-half years old when I got into the band; they were ten years older than me. But about 4-5 years into the band, I had now taken over all songwriting and was driving the band towards my early influences — at least my own interpretation or what I thought was Van Halen and AC/DC and so and so. Whenever I would sit down and write the song, I probably would write the song much more from a Dylan, and later on, Springsteen foundation. On vacation, I took by myself to Rio de Janeiro in 1980; this was when I discovered The River by Springsteen. So, that was my introduction to Bruce Springsteen. At that moment, I’m sort of preparing myself to lean up against David Lee Roth and grow my hair, but when I sat and listened to The River in this guy’s apartment that I was visiting, instantly, I heard my childhood; I heard my early years again. I was sort of awoken for the first time to something that felt familiar.

Andrew:

As a teenager, you joined the band Mabel and took the local music scene by storm. What was the identity of the band when you entered the picture, and was that something you saw yourself doing for the rest of your life?

Mike:

It wasn’t a boy band in the sense of New Kids on the Block and those, like, five guys that stand there and dance and somebody else writes the music. This was a Rock band that had been playing as a trio for a long time. When I got into the band, they had somewhat of an idea that they wanted to go a little bit more, not teeny-bopper, but that whole movement that had come with both Slade and Sweet, but also the Bay City Rollers and Gary Glitter and David Cassidy. All that kind of stuff that was not necessarily just the music, but more the overall movement. So, when I get into the band, first of all, I didn’t have any goals of becoming anything in music. I was playing a little music in my youth club, but I was also doing karate and football, so it’s not a matter of that. It just sort of happened. From that second, I said, “Okay. I’ve signed a lifetime contract to Rock ‘N’ Roll.” Day by day, I just took it in and tried to become better at it and learn. I have said it many times, and I’ll say it again – it took me a very, very long time until I actually could look in the mirror and say, “You’re getting close.” And it’s probably not before I started playing with Vito [Bratta] in early ’83.

Andrew:

Earlier you mentioned David Lee Roth. You actually met David before coming to the states if memory serves. How did those events transpire and did David offer any words of advice?

Mike:

I met Van Halen in ’81 in Spain because we were at the same record company, and I had the opportunity to sort of be “the guy” for the band for the three days they were in Madrid. It was an exceptional experience because no one really knew they were there; this was just a big Warner Bros. world promotion tour for Fair Warning. So, I got really, really close to the band, and they really let me into their little world. I observed all these different things, both as a fan and as a student. One thing was, I thought that when I would present my record to David Lee Roth, he’d say, “You’re gonna be our next support band in America.” Instead, he says, “Man, you gotta get over there and play the clubs for the next ten years.”

The following year, ’82, I went over there with Mabel. We were now called Lion and ended up playing about 10-12 shows in the New York area. The final show we played was at L’Amour, where we were playing before Vito’s band Dreamer, which was basically just a tribute band playing Van Halen, AC/DC, Iron Maiden, etc. I met Vito in the dressing room – it wasn’t like we exchanged any words – but I sat there and watched him play his guitar through one of our little rehearsal amps, and I just realized that that’s the level I needed to be with. I thought that we came over to America with our chops, and suddenly, I just saw someone who was actually my age and had the hair, had the guitar, all the shit. November ’82, we went back to Denmark, and the guys were just tired. We had no money, but my fuse had just been lit. So, it only took about two and a half months before I got a little bit of money together with the help of my mom and bought a one-way ticket to New York. About a couple of days, after I’ve been there, I run into this girl who gives me a phone number and says, “This is the guy you need to call.” And it was Vito.

We got on the phone with each other, and he remembered me. We bullshitted each other for a couple of hours and got together a couple of days later. Then we started the early beginnings of what White Lion would eventually end up, with the bass player and the drummer from Vito’s band. Bit by bit, they, as many other people I’ve played with, ran out of steam. But Vito and I felt like we had a commitment here, and Vito opened the door to George and Michael [Parente], who owned L’Amour. They remembered seeing me too and also thought that something should happen there. We started looking for members and went through a few changes until we finally became White Lion in early ’86, with James [LoMenzo] joining the band as the last member.

Andrew:

The New York club circuit featured an influx of talented bands at that time. Vito was in Dreamer, you were in Lion, Greg was in Cities, and James was in Clockwork, for example. What are your memories from those club years?

Mike:

Well, obviously, that had been some years before I got there; I’m sure the late 70s. I can’t remember when Vito said he started playing for the first time. But the thing you noticed, which of course doesn’t happen anywhere in the world anymore, were people going out for the night, no matter who was on the bill. The thing was that the audience was there for the same reason as the band – to deliver Rock ‘N’ Roll, man. Some people in the audience looked a little more dressed up than the band, but there was such a positive vibe. There was nothing but fucking energy. Just the energy in people wanting to be part of this. It was a complete congregation for the same cause.

Andrew:

With all of those bands vying for an opportunity, how competitive was the scene?

Mike:

I guess Vito was telling stories about how bands were competing a little. I’ve had the talk with Dee Snider a few times because when I got to New York, I was hearing about this guy Dee and the band Twister [Sister], and Vito sometimes would say, “Nobody sees Dee until he gets on stage, and when he gets on stage, he just tears a room apart!” Later on, I’ve had a similar conversation with Dee about the scene. These were the days when bands were riding around all night throwing flyers on the telephone poles. No doubt that Van Halen started that whole thing and then, after that, Mötley Crüe. Then, [it was] how many 412 Marshall cabinets could you have on stage. Then it’s, “We gotta bring extra light in and rent a wireless microphone so the singer can run around.” All these kinds of things, we knew, when we were on stage, it was not just the music. It was a show, too.

Andrew:

I imagine transitioning from Copenhagen to the bright lights of New York City must have been a bit of a culture shock. What was your initial impression of New York when you arrived?

Mike:

I never felt more at home. Even though we ended up in Queens, New York, out in a place called Flushing Meadows, on the border of Jackson Heights. Today, it’s like, “Fuck, man. That’s Little Columbia.” To us, it was Beverly Hills, man! It was the best thing. We’d just arrived and saw there was a big supermarket there and we just ran in there. On the first day, we spent over $1,500 in the supermarket, overbuying everything. Actually, it was me; everybody was just following. I was just absorbing it. I said, “Finally, I can let my hair out, and when I say something, people understand what I said,” because nobody wanted to speak English in Spain.

Andrew:

In the band’s earliest years, what was the draw like in clubs? Did you find it to be more of a gradual following or was the band pretty well-received right away?

Mike:

We weren’t playing that many shows; we only really played two shows with [bassist] Felix Robinson. One was at L’Amour Brooklyn, and the other one was at L’Amour Lower East, which was in Queens. Those are the only shows we ever played with Felix; then we sort of said goodbye to Felix. Then Dave [Spitz] came in, and then we started playing a lot more and jumping in on a lot of bills. The scene was exploding; the scene was huge in ’84. When James comes into the band, and we start finalizing the songs that Vito and I wrote, we don’t really play that much. Then we go back to Germany, where we recorded Fight to Survive, and recorded the Pride album, take one. We come back, and already in the car on the way back from the airport – we’re all sitting there in the big limousine with our managers – and we’re listening to it. Even though we’d just traveled for fucking eight hours, I remember just listening to the album. By the time we come to the house in Staten Island, which was kind of the home base, everybody’s kind of silent. Everybody just looks at each other, and I think it was Vito who said, “It’s not good enough.” Then we decided it wasn’t good enough. We didn’t have a record deal, but we decided to do the same thing we did with Fight to Survive – record the album first, then finalize it, and then shelve it as the final album.

But instead, we just decided to work and do a few gigs here and there, trying to come up with a game plan about how we can do something next. Then we get a phone call from Michael Wagener sitting out in California saying, “I wanna work with you guys. I’ll put up the studio; I’ll find some living quarters and some per diem cash. Just get ready to come out here.” We went out there in January of ’87, while our managers in New York were trying to close a record deal with Atlantic Records.

Andrew:

Before finalizing the classic White Lion lineup, what incited the incessant lineup shuffling on the heels of Fight to Survive? What qualities were you and Vito looking for in bandmates?

Mike:

If you’d have asked Vito and I in those days, we were probably looking for members who could have fit into Mötley Crüe, or Ratt, or Cinderella – people that were dressed for Rock ‘N’ Roll and giving their life to Rock ‘N’ Roll. Nicky Capozzi [drums] wasn’t one of them, and Felix Robinson [bass] was far from it. But we had run out of steam, and Nicky was Vito’s friend – a phenomenal drummer but a hermit that, in reality, just wanted to sit home and play drums. So, [Nicky] left the band by himself, and Felix just did not fit in at all. We were struggling, man. As opposed to L.A., New York did not produce a lot of those kinds of guys that we were looking for – at least at that time.

So, Dave [Spitz] comes in and replaces Felix. It was great getting Dave into the band; he had a lot of energy. He couldn’t sing, it was a little bit of a letdown, but he was a great friend. But somehow, behind our back, he was also shopping around. He got invited out to record this solo album for Tony Iommi. Then suddenly, behind our backs, he gets asked if he wants to join the band and then leaves. During the time with Dave in the band, Nicky wasn’t into anything. He hated everything about it; he just loved drums. He loved just to sit home and watch TV and play drums. Then Greg came in, and we played a lot of shows with Dave and Greg. The second Dave left, we had a very short period – I think we played with another guy for a short while – but once James came in, it was love at first sight. That was as much harmony as we could ever call harmony in White Lion. It was a good time; there was a lot of energy, everybody was happy. The best time in White Lion was always the chase, not the catch.

Andrew:

The debut album, Fight to Survive, encapsulates the band’s raw energy and sound, but never received the proper recognition. Tell us the backstory behind that.

Mike:

The only challenge is that we still do not know why we got signed to Elektra Records for a large amount of money. Then after a few months of preparing the album release, doing the album cover, and all the different things, they decide not to release the album, and they sort of released the band from the album deal. We still got the advance from it; they almost wrote us off as a mistake for some reason. We still don’t know. We still don’t know. It obviously ground us for about a year, then somehow, our managers started working without telling us. They had some contact with a publisher in Japan, who got it over to JVC Victor, who loved the album, signs the band, and also signs the band for two more albums. This means we would be releasing the Pride album and the Big Game album on JVC. Then from Japan, the album became – those were the days where record stores around the world were breaking bands. They were importing the album to Germany, France, England. And bit by bit, suddenly the albums starts appearing on the charts and all these magazines; No. 1 on the import charts; No. 1 underground. And in those days, fans fucking paid attention to those things because suddenly there’s big of a hype for the band, and now the album starts getting imported to America. In the Tri-State area, Jersey, there are a couple big local record stores that are all for Rock, and suddenly the band is selling albums and filling clubs.

Andrew:

What was the vibe in the band like at the time you flew out to California for the first time to record Pride at Amigo Studios?

Mike:

It was the greatest time in the world because we were four guys living in one apartment; we were four against the world. There was nothing else but White Lion in our life. Nothing else but White Lion. There were minimal, maybe one or two, small confrontations in the studio, debating a little bit over a musical part or something like that. Michael [Wagener], of course, was the catalyst in just creating this phenomenal atmosphere. Michael has worked with a lot of bands, especially a lot of bands after, but when he worked with White Lion, he probably saw some discipline that he maybe had not seen with other bands because we knew our shit when we came in, and we were very much in harmony.

Andrew:

When White Lion was out on tour with Aerosmith for the Permanent Vacation Tour, was there any notable camaraderie between you and fellow frontman Steven Tyler?

Mike:

Don’t forget; I was together with Steven Tyler when he turned 40. [Laughs]. We had a lot of days off, so he and I had done some extreme things of a different kind that he was known for. Those moments — even talking about them — it was just great. It was fucking excellent. It was the real deal, and it wasn’t forced. It was natural because we were in the band, and Aerosmith respected us and acknowledged us. All the guys in Aerosmith invited me in for dinner every night in their dressing room. I got a great bond with them. Joe Perry would talk to Vito once in a while, but none of the other guys in the band would ever totally bond with Aerosmith in the same way that I would. But that was also my personality; I went to the movies with Joe Perry, and I went to a water park with Steve Tyler, just him and I. You couldn’t make this up; you couldn’t plan it. It just happened because it happened.

Andrew:

You were already accustom to the spotlight from your time with Mabel, but following the immense success of Pride, the band suddenly graduates from L’Amour to much larger venues. How did the band handle the transition to playing arenas?

Mike:

I’d already prepared for that in Mabel, but when White Lion started, we prepared for the arenas from the beginning. Our rehearsal room underneath the stage in L’Amour was a large room with mirrors in front. Our managers said, “We gotta prepare for the big days. We’re not preparing to play the club tomorrow. We’re preparing ourselves for arenas.” So, when we stepped out on the arena for the first time, doing four shows with Triumph because I think Yngwie Malmsteen had been thrown off the tour, or something had happened, or someone got sick. That night, we fucking went out on stage and had our show down pat. We were born for that stage.

Andrew:

White Lion was unfairly grouped with the Rock acts of its time, but the band offered infinitely more depth and substance than its contemporaries. As a songwriter, what inspired you to deviate from the blueprint?

Mike:

It wasn’t that important at the time, but in the long run, it would survive. This is one of those things that whenever I talk about these moments when I find myself – obviously, I’m still a young man with my hair growing longer and longer every day – but whenever I would sit down and start working my way through lyrics, I would always have an angel and a devil sitting on each of my shoulders. I would find many moments where I was caught in where I was going, and every time I went for tits and ass, I felt a large amount of uncomfortability. I have been on stage doing, at times, small moments of a third-ranked David Lee Roth rap and stuff. But I was never a person living on sexual innuendos, never talking about that stuff from the stage. I imagine that the persona that I was on stage – the tight fit of the pants, the flat stomach, and the hair – I was good-looking and a strong frontman, but I wasn’t projecting what Bret Michaels was projecting and what Vince Neil was projecting. They were so over-sexed that they couldn’t say anything else. So, whenever I had the opportunity – if it’s “Lady of the Valley,” then later on “Cry For Freedom,” “If My Mind Is Evil,” “Broken Home,” and stuff like that – this is also, once again, when I see connections to my upbringing and my home in a very, very free, but also worldly-European home. As opposed to my three bandmembers, who at that moment had only been in their own country, I had already been many places in the world. I had grown up with a large amount of history and knowledge; that the world is round and things are not just happy days; Fonzie and Richie Cunningham. But at times, with “Little Fighter” and stuff, the word concern from, maybe Vito – not Greg and James – and the record company, that saving whales is not for Rock ‘N’ Roll. I can’t tell ya how many people – if it’s military, if it’s handicapped in a wheelchair, or somebody that lost their best friend — uses “Little Fighter” as their savior.

Andrew:

Well, I think the music still holds up to this day. “Little Fighter” has an incredibly powerful message.

Mike:

Yeah, I mean, I think “Little Fighter” holds much more today when I play it, when you see my face, and you hear the way that I sing the song and interpret it. You know, it came at a time when we’re still so caught up in the colorful clothes and stuff like that. Even though I was hinting at it, there wasn’t space for creating a dark video for “Little Fighter” in 1989. It’s just one of those kinds of cross things that I’ve obviously learned in life, that sometimes you get caught with a great idea at the wrong time.

Andrew:

You mentioned how “Little Fighter” holds up more today. The same can obviously be said for “When the Children Cry.”

Mike:

Yeah, of course. Exactly. This was 1985 when I wrote a large amount of that song, and then I sort of finished it with Vito, but the song is basically written. What am I doing living in my manager’s house, sitting and singing “No more presidents/And all the wars will end/One united world under God” in 1985, and probably that night I went out to L’Amour, and I had some Budweiser’s and was looking at girls? This is true Denmark coming out of me right there. And I think it probably is one of the reasons while the song will stand the test of time, until the end of time. It is timeless; the message is stronger today than it was then.

Andrew:

You’ve mentioned that you can’t sing as you did in 1987 and that you were singing outside of your comfort zone. What did you have to do on a daily basis to keep your voice in top shape so that you could go out on stage and deliver each night?

Mike:

I’ve always said, when Vito and I wrote “Broken Heart” – which is the first song, and it’s also the highest song that I’ve ever sung – I think it was just a matter of, that’s just sort of what happened. Then sometimes, Vito and I would write the songs, and then we would take them to the rehearsal room and maybe change them. When I would start singing down there, I wasn’t able to hear myself, so sometimes I would go up an octave, or I would ask Vito to change the key or something before we nailed the song. That hasn’t happened many times — Vito changing the key — because a lot of the songs were written around his riffs, and those riffs cannot be moved to another key. But once we really, really starting touring heavily, obviously, it became a lot of pressure. When we were touring with Aerosmith or when we were touring with AC/DC, we were doing five nights a week. Even though we were just playing an hour, it was still full voice all the way. At times, I was struggling, and other times, adrenaline would lift me up.

When we came to write Main Attraction, which we used probably about three-quarters of the year writing, we both felt it was almost like a rescue mission because we didn’t feel we had enough off time before we started Big Game. So, this time, we really wanted to work with songs and have time to listen to them and change things. On Main Attraction, I really wrote for my voice at that time, also keeping in mind where we had been. Also, which you hear only a year or two later when I record the first Freak of Nature album, my voice is naturally changing at that time. So, it’s just one of those things. You can actually notice it if you ever listen to Journey. By the time Journey does the album Frontiers, Steve Perry is already taking a little bit of a different tone to his voice. It’s almost like it’s getting wider than higher – even though he’s still capable of doing that. Even though in Freak of Nature, there’s some really fucking high stuff, but it’s probably a little bit wider than it is higher.

Andrew:

You and Vito had tremendous foresight and always remained focused on what’s ahead. For example, I think it was just days after your tour with Stryper that you started writing for Big Game, right?

Mike:

That should never have happened, but it happened. I was saying before, that when we started writing Mane Attraction, we felt it was a rescue mission because Big Game had not done what it should have done. To us, the Pride album had been two years. It was still on the charts, but to the record company, they’re looking more about – I don’t know why somebody could not see, not just does the band need a break, but the band also needs to disappear from the magazines and from MTV so when we come back with something, people are excited again. But by the time, the last show is around Thanksgiving with Stryper, we were back out on the road with Ozzy late June ’89. Fuck, that’s seven months where we’re writing an album, recording an album, preparing for a tour, etc. Like I said to you when we started the interview, I have all the answers now.

Vito and I, as the leaders of the band – and James and Greg could have been just as much a part of it – did not object. We’re now in a place where a lot of stuff is going on; there’s also a lot of new bands coming on. So much is going on, and you want to be a part of it – you also want to take a break from it – and the people that are supposed to help you make those decisions are looking more for you to get back out there so we can make some more money and they can get their share.

There are some great, great songs on Big Game, but the album is unfinished. It’s just too rushed. We needed to get back down on the ground and feel humble again. Suddenly, the money was rolling in, we were having a great time with Michael, but we were having almost too great of a time. I’m not talking about drugs and alcohol – none of us were doing any of that kind of stuff – but we weren’t really sitting down and listening and thinking. I know all of us are really unhappy with the mix. But at that time, we were all confused. Vito and I always wrote an album; we didn’t write filler. I can’t say that we wrote them in the order they became, but we knew sort of the different songs that we’d written, and when we got to song No. 10, we knew we were writing the final song, both for Pride and Big Game. So, now our manager said, “We need a track.” And suddenly, I say, “Let’s do ‘Radar Love.'” So, we start playing “Radar Love,” and that song is such a fucking great song, but the song has already been tested and played for generations. When we go into the studio, the band, even though they’ve never fucking played the song, they’re so comfortable in playing the song that you can hear it on that track, and it’s about the other tracks and the performance.

Andrew:

Since you mentioned “Radar Love,” I have to ask you about the video. I believe you rode your motorcycle in that as well?

Mike:

Imagine going out and doing a seven-minute video, and MTV said, “It’s cool.” That was like a fucking kid in a candy store. James had his motorcycle; I had my motorcycle. We had just finished the last show with Ozzy Osbourne in Sacramento, and we drove on the tour bus and woke up in front of the biker bar where we were filming the video and then went straight in there and started filming. Those were the days. As you and I talk about this, there’s a lot of warmth coming up that also goes, “Of course, we had a great fucking time.”

The more years that go by, the more you cherish it and the more you are able to answer back and give honest answers that aren’t thought-out or prepared—full, from the heart, man. To me, I don’t want to go back; I can’t go back. I look in the mirror; I know that I’m not 40 anymore; my knees hurt, things like that. But when I’m engaged with you right now in this interview, I can smell the summer of ’89. I can be there out with Ozzy Osbourne and then later on out with Cinderella and going to Japan.

Dude, it was so fucking large. You were asking earlier on about the feeling in the clubs; how was the feeling in the arenas!? I mean, every night, a new arena; you show up, there’d be four or five thousand people in the parking lot already at twelve o’clock, listening to the local radio station. All car stereos turned on, fucking partying, having a good time. No violence, no all this fucking bullshit that’s going on right now. It was such a great fucking time.

Andrew:

How was the No Rest for the Wicked Tour with Ozzy? That’s an interesting bill.

Mike:

Obviously, we’re coming up. Nothing beats ’88, being out with Aerosmith and AC/DC. Out with the bigger bands. Ozzy is giving us our own full production in front of his stage, but the Ozzy Osbourne tour was a tough tour. He drew his own fans. Not a lot of them, but there was quite a little bit of heckling and stuff like that. It was a little disturbing. The Aerosmith and the AC/DC Tour was just solid, sold-out. We were so fucking hungry on the Pride album and such a tight unit. When we go out and do the Ozzy Tour, we had our own aluminum stage ramps and all kinds of shit on stage. Everything we had, we tripled. We got two tour buses; we got our own semi-trailer just with our gear. You have a tendency to maybe lose a little bit of control.

Andrew:

The band essentially caught the final wave of the 80s yet managed to leave a lasting impact on the era. That’s quite a legacy, Mike. So, where was the disconnect in the final days?

Mike:

Well, I’m happy that I can also provide you with a positive side because the memories of White Lion are very positive. The legacy of White Lion is positive. There weren’t any broken windows, smashed hotel rooms, and stuff like that. Maybe the ones that were guiding us didn’t manage to talk us through the small problems that we had. We could definitely have solved the issues with Greg and James. It was all just financial kind of stuff; of course, we could have solved it. I don’t know why there wasn’t the willingness. When I broke up the band, if Vito had persistently called me and fought for stuff like that, we could possibly have been a team today and taken the band in a different direction. Somehow, the energy that Vito and I had, a lot of times probably more mental energy to build a band and fight for the band, also disappeared from him when push came to shove.

Andrew:

When I spoke to Nothin But A Good Time authors Tom Beaujour and Richard Bienstock some months ago, I asked them if they could see any band from your era live and at full-strength, who would it be and why. I chose White Lion. Had there been a fifth album, what direction was the band ultimately heading?

Mike:

At the end of the time, when we finished a very large and big-scale European Tour for the Mane Attraction album – unfortunately, Greg and James decided to leave the band after that – the band is on the edge to take the next step. I’ve said it many times; I think that not so much musically, but were going towards Journey – Rush would be too big of a step – but we wanted to go that way as a band; a Deep Purple, grown-up band. The kinds of bands like Journey, Styx, and those bands had been in the 70s, where it was all about great musicianship. Step-by-step, in our own way, we were going there. Had we come back with an album after Mane Attraction, that’s the way it would have been, with major keyboards as a fifth member to allow Vito to do a lot of different things.

Andrew:

Mane Attraction sounded distinctly heavier compared to previous albums. Was the band at all influenced in that direction following the No Rest for the Wicked Tour?

Mike:

I don’t think it had anything to do with Ozzy. He didn’t inspire us at all. I think that when you look at a song like “Lights and Thunder,” it’s an epic song, and there’s not a lot of 80s bands that we are compared to that had done a song like that. I don’t need any medals for it, but it’s just a fact. This is where Vito and I are able to feed off each other. I can’t remember how the song came about, but let’s say it starts with a big guitar riff, and then suddenly I take it down to the verse. We had a talent that, when we suddenly could see where a song could go, we were willing to explore that, and we would chase it and see where it led us.

Surprisingly enough, [Vito] actually really enjoyed “Dr. Feelgood.” I think it was probably just the song “Dr. Feelgood;” there was just something about that song that turned Vito on and inspired him. I’m positive that the song “Leave Me Alone” has a little bit of a “Dr. Feelgood” inspiration in it and probably even a little Guns N’ Roses. I could hear moments of inspiration that had just entered him.

Andrew:

The last time you and Vito graced the stage together was Sept 2, 1991, at The Channel in Boston. At what point did you reconcile in your mind that it was over?

Mike:

Only a few days before, but it had slowly started. This is something that I’ve never really talked to anybody about. As I was getting close with a lot of people in Los Angeles in the music business, there were some other managers – in this case, they were managing our producer Richie Zito – and we became really good friends and started hanging out. And maybe at times, I was sort of looking to them as, “Wow, I wish my managers were like that.” So, little by little, I was sort of pulling away and not really respecting anything from our managers. After Greg and James left and we got the new guys, we decided to go out in America for about three weeks in some clubs and just feel out the band. And little by little, we get to this. It’s like the call of the wild; you suddenly hear voices at night from the woods. One thing leads to another, and I think it was two shows before we were playing the Boston show, which was also the last show on the tour. I think we were playing a big amusement park up in Rhode Island, and the power goes out, and Vito and I are standing backstage. I go to Vito and say, “Listen, man, when we play Boston, it’s going to be the final show.” And Vito just goes to me, “Okay.” We’ve never spoken anymore about it. He never said, “Tramp, why did you say that?” And then, after the show, the next morning, I fly back to L.A. Vito flew back to New York. Nobody calls. The record company doesn’t call; management company doesn’t call. No big announcement is made. In the back of the plane, I’m already creating Freak of Nature in my head because that’s how I’ve always been – hit the ground running. I don’t throw something out before I’ve got something new.

Andrew:

In retrospect, was taking a hiatus something that you considered? It’s mystifying that something that special was simply allowed to fade away.

Mike:

It was time, and we hadn’t really been together long. In reality, Vito and I meet in ’83, and here we are only seven-and-a-half years later. At that time, Vito and I were definitely apart socially. Obviously, the music speaks for itself, so we were able to write Mane Attraction. That’s not just on luck; we spent a lot of time. I came over to Vito every day, and he flew out to California, I was living in a place, and we were writing and built up a little studio over there. If I had had the same friendship as I had with James, where James and I used to paint houses down the Jersey Shore together, and we had a buddy-buddy friendship. We did things together, the kind of friendship that I had with Freak of Nature. The band doesn’t finish after rehearsal; we continue someplace else. If Vito had also fulfilled that part of my life, there would have been no way the band would have broken up. I’m not blaming Vito – Vito hadn’t done anything to turn me off – but it’s probably what he didn’t do. And that is, thinking that we need to be more than business associates.

Andrew:

You and Vito have vastly different personalities, yet when it came to the music, there was this innate chemistry. How did it flow so beautifully together?

Mike:

Yeah, I mean, obviously, it’s a little bit of a mystery. I’m outgoing in the way that I’m very upfront and want to be a part of everything and share everything with everyone. Energetic. I’m actually completely like that — morning person, daytime, nature, stuff like that. In the early years, we were a lot of times out in the club, because our manager owned the club and our rehearsal room was underneath. In Vito’s defense, when we were on tour and out playing and stuff, Vito would be engaged in as much hanging around and having a drink – I mean, White Lion was never one of those bands – but just within our borderlines. Why he chose later on to be a recluse and just sit home, I don’t really know. But I respect Vito all the way, and I’m very happy that the last couple of years were sort of like, “If there ever was a bridge that started burning, we put out the fire. We repaired the bridge.” We don’t talk a lot, which in reality, I’m gonna put in Vito’s hands because he knows I’m always here. It’s up to him; if he has something on his mind, he knows that I’ll be there for him. And we’re one hundred percent in full agreeance that we would never attempt a White Lion reunion.

Andrew:

You’re asked that reunion question in seemingly every interview, yet you’ve clearly outlined why the band is to be preserved for its time.

Mike:

When you have to get to the point of saying, “If you don’t take no for an answer, if you don’t take this for an answer,” then let me say it in this way; No. 1, I don’t want to, and I can’t be Mike Tramp 1987. And we’re also not going out to do a half-assed White Lion version. It’s different than in my solo band that I will play several White Lion songs, but that’s me interpreting them at age 60 years old. They’re still very close to White Lion that when you look at the singer in the middle of the stage, and you hear the song, you feel that both are at the same place in time. I’m not dissing anyone or anything, but I just think there some people out there that shouldn’t be doing what they’re doing. It’s like watching a boxer with broken wrists and just being pummeled, but he just doesn’t wanna give up. Obviously, it looks like a lot of people that were married to the 80s were never able to move on from the 80s. When I moved on from the 80s, and I started Freak of Nature in ’92 and then in ’96, I started my solo career – and now 12 solo albums later and a career for the last 25 years – this was a life change. White Lion is preserved in its time. Freak of Nature is preserved in its time. And now, basically, for the last 25 years, I’ve sort of been the same and not changed from that.

Andrew:

It’s refreshing to hear that in this nostalgic age, where you’re seeing bands trotting out lineups where there may only be one original member out there, you refuse to entertain that.

Mike:

And you probably also remember that I have gone out and said that that short moment when I lost the reins, focus, and direction, and for maybe a period of about two-and-a-half years, was trying to first do Tramp’s White Lion and then went as far as to have some shows announced as White Lion. When I pulled the plug from that, I also assumed the blame and said, “I’m the one who could have said no from the start.” But obviously, there was still a little bit of doubt in my life, in my career, that allowed me to pursue this thing that, as soon as we started it, I knew that I wasn’t at home.

Andrew:

If Vito had no intention of returning to the spotlight, why do you think it meant so much to him that White Lion remains preserved in its time?

Mike:

Obviously, that’s a great question. It’s also the million-dollar question. He did say to me once, “Mike, it’s not that I have a problem with you going out and doing White Lion songs or someplace being announced as White Lion. But I don’t want to turn on YouTube and see White Lion and they’re playing this in this song and then see another guitar player playing it. White Lion was you and I and that’s what I want preserved.” And I could only agree with him.

Andrew:

After the three Freak of Nature albums, you embark on a successful solo career of 25 years and counting. Where did the inspiration come from to venture off and pursue your own projects?

Mike:

I’ve been in three bands. That’s equivalent to being married three times, where the first one takes the mansion, the second one takes the children, the third one takes the bank account. You’ve got nothing left after that, and I said, “I’m not starting over.” So, the second that I start writing for myself, I don’t have to think anymore; I am just me. Everything Mike Tramp writes is on those solo albums. I’m not trying to be Springsteen or anything like that; I’m just saying I identify with it because that’s the sound I grew up [along] with Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, and Dylan; this is the stuff my mom introduced me to. This is how I learned to play guitar; it’s also where my limitation of playing guitar ends. That’s where I am as a solo artist, and that’s how I want to sound as a solo artist.

Andrew:

I thought that Cobblestone Street was a crucial chapter in your journey. What prompted you to return to your roots?

Mike:

Yeah, I mean, Cobblestone Street is going back to the start. The next six albums after that were all recorded where I was born, in my neighborhood. And the streets of Copenhagen. That’s what it’s all about; taking it back to the beginning and then re-building it from there. See where your foundation of your songwriting comes from; the essence of who you are. There’s not one song on my solo albums that are not about me. I don’t have to create anything like that. I just write about where I am in my life – the exit I pulled off – thinking about where I’m going and where I’ve been.

Andrew:

So, Mike, obviously, the days of the tour bus and MTV fame are long gone. However, you remain one of the hardest-working musicians in the industry. What keeps your fire burning after all these years?

Mike:

My songs are an extension of me. I don’t write because I have a record deal saying you have to deliver an album. I write when I feel the songs start knocking on me. So, just like I wrote with Vito, when I start writing an album, I write it like a book. Probably not in the order that the songs will be in, but I know when I get to song No. 10 that I have the full story completed. The strength of Mike Tramp is being realistic. It’s also what allows me to tour the US, driving a rental car, walking in the front door with my guitar in one hand and my little mixing system in the other hand, going up on stage to do the soundcheck, grabbing a burger or steak at the bar, going back to the hotel, taking a shower and coming back, playing and telling stories for two hours, then going down and selling my t-shirts and my albums and becoming friend with a lot the people because we’ve become a family. I have record sales between 5-10,000 worldwide. I build everything around that. I don’t ask for anything more. I come from nothing, and it’s where I’m strongest.

Andrew:

I’d be remiss if I neglected to mention the immense amount of respect I have for you, Mike. From the streets of Copenhagen, you and your bandmates ultimately willed your way to the grand stage of Madison Square Garden. You came to the states intent on carving out a career in music by any means. You said it yourself at the top of this interview, you signed a lifetime contract to Rock ‘N’ Roll long ago. You fought incessantly for a place at the table and never let anything obstruct your path. That, to me, is incredibly inspirational.

Mike:

I truly appreciate that. Again, hindsight is 20/20. I’m the wisest man on earth right now. I made some good money – no, I did not blow the money; I just used the money. But I came from nothing, so I wasn’t about to buy stocks, or real estate, and things like that. I’ve had a great time; I’ve had a great life. I know a million people around the world. There are so many people who know me, and most people will say the same thing about me. I don’t feel that I would have any enemies out there; I don’t think anybody would call me an asshole. If they did, they’ve probably never met me and probably had a girlfriend that liked me. It’s a combination of survival, but it’s also because it’s who I am. And so, I started using that to my advantage.

To add to that, and this is one of those magical stories; it’s very, very short. Early in my life, back in my old neighborhood, I’m walking down one of these little streets. One of the basements had the window in it, and it turned into a gallery, and there’s some paintings hanging. I see a guy painting down there, and the thing he’s doing really captures my eyes. So, I knock on the door, and he says, “Come in.” I said, “Holy shit, man. This thing speaks to me. How much does a picture like that cost?” He says, “It’s not for sale.” I said, “What do you mean? Why are you painting?” … “Because I like to paint.”

Andrew:

Let’s talk about your latest effort, Everything is Alright, which comes out on May 21.

Mike:

Yeah, Everything is Alright is obviously honest. Half a year ago, I released Trampology; that was a double, 20-song anthology. The record company wanted to do a single version of that, and in the meantime, I had been part of something that we called the Eurovision Song Contest. Each country always had its local — and I was sort of part of that in Denmark. This song that I wrote for that, Everything is Alright, has now sort of become the main track on that album. So, they’re releasing that. For somebody who doesn’t have any Mike Tramp, it’s an album with ten top-ten tracks and a couple of new ones.

Andrew:

Lastly, Mike, what’s next on your docket?

Mike:

Right now, they’re opening up here, and I’m playing a couple of solo gigs next week and stuff like that. Obviously, I won’t be doing anything internationally before ‘22. And that will be announced in the near future, too, once we decide that this is what’s gonna be. So right now, it’s about riding ’21 out and hopefully getting vaccinated soon. Not necessarily because I want to be vaccinated, just because it becomes sort of a necessity and a requirement before you can step on a fucking plane. One good thing about it is, I live on a farm, so I’m out in nature all the time. I’m not around in a big city. I don’t go to bars or anywhere. I have my studio here, and I’m just waiting it out.

Andrew:

Well, I hope you enjoyed reliving your early days in music with me. Hopefully our conversation today evoked many fond memories from the heyday.

Mike:

I’m gonna send Vito an email right now saying, “Just checking in on you. Just seeing how you’re doing.”

Interested in leaning more about Mike Tramp? Check out the video below:

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

2 thoughts on “An Interview with Mike Tramp of White Lion”