What do you think of when you think of a vinyl collector? Do you envision an obsessive, possibly un-showered, greasy, pale blob of a person, hunched over their “precious” artifacts? Yes, you know the type…seldom goes out in daylight, spends most of their days in the veiled shadows of their (or maybe their mother’s) basement, only venturing out to hoard more slabs of wax. Sound familiar? It could…or maybe it should, given that it’s basically the stereotypical image of the record collector. Well, then again…there is the other side of this proverbial coin. You also have the vision of the hip, young guy or girl. Yeah…skinny jeans, Wolverine 1000 mile boots, matching leather belt, horn rimmed glasses, sweater vest- the whole deal. And of course, they have the most refined taste and they are more than prepared to tell you what you’re doing wrong. Perhaps that sounds familiar, too.

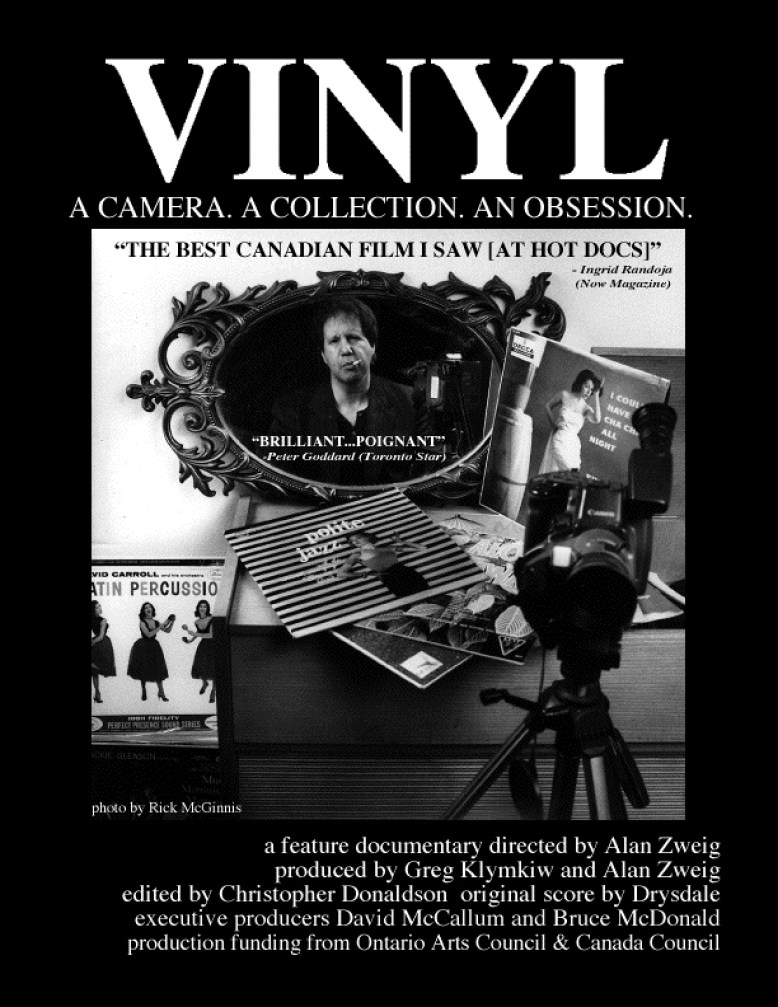

So, where does Alan Zweig come into this? Well, Alan, like so many of us, is a record collector. He doesn’t really fall into either of those categories…not all of them anyway. But there in lies the point- none of us do. This was never driven home further than in Alan’s 2000 documentary Vinyl. The film itself has an interesting legacy. It’s one of the first true vinyl docs, if not the first, but more importantly, it shined a light on vinyl and the collectors. It doesn’t really tell a story, but it’s more a series of snapshots which reflect record collectors in all their unique, weird and sometimes obsessive glory. The film is somewhat infamous now. Some love it and consider it a moment where vinyl finally got its due, and other feel it showed the hobby in a more negative light than they would have liked. Say what you will, but the film is true to itself, its intentions and its creator. All my personal opinions aside (I like it), I implore you to watch it for yourself and cast your own judgement. Art is subjective after all, isn’t it?

Anyway, to make a long intro to a long interview even longer, Alan is working on a sort of follow up. Not a true sequel per say, but more of a spiritual sequel. This time around, Alan is looking to celebrate records and collectors with an emphasis on positivity, which should be interesting to say the least. I look forward to the film’s release later this year. So, keep your eyes peeled for Records at the back end of 2021. It will be interesting to compare and contrast the two films when all is said and done. Also interesting is this chat with the film’s creative mind, Alan Zweig. Alan is an unique guy, with a singular…swagger. Enjoy this one. Cheers.

Andrew:

Alan, thank you for taking the time to speak with us. This last year has been rough, right? How are you holding up during this seemingly ever-raging dumpster fire?

Alan:

I’m good. At the beginning I was scared, being an obese senior with Type II Diabetes, but I don’t think about that so much now. I was out there for over two months in dozens of homes interviewing people and I didn’t think I was going to get it from them and they weren’t afraid either; and sure, I could get it from someone the day before my vaccine is arriving but I’m pretty careful and of course I’m still afraid, but I don’t think about it much. I did have a very different plan to make my film and it all got blown away and my crew and I will probably always have a tinge of regret that we didn’t have that adventure, but we had fun and we picked up a few good records along the way. I have a whole other answer to that question involving my time with my daughter and my girlfriend but I guess that’s for a different interview.

Andrew:

Tell us about your backstory. What was your musical gateway so to speak?

Alan:

I’m not sure I take your meaning. You’re not asking what music I was into that got me into record collecting, are you? Maybe you’re just being metaphoric. So, I’ll leave out records and try to give a very quick sketch. I was born in Toronto in the early fifties, the second of four children of a Jewish accountant and a housewife.

I was a teenager in the sixties. I dreamt of running away from home and living with the hippies in Haight Ashbury but I was a bit too young, sheltered and timid so I stayed at home, went to university and was on my way to a law school when I decided to put a stop to it.

I had never seen myself as a creative person or an artist but I had had one experience helping some friends make a little movie, and I enjoyed that. So, after university and after a couple of trips to India, I went to film school and fell in love with filmmaking. But unfortunately I didn’t have the personality to know how to make it in that world, and I lived in Canada where the film business was pretty challenging so I floundered for decades.

In the mid-nineties, I got some money to write a script for what I hoped would be a low budget feature, based on a story I had written about a guy whose wife sells his entire record collection when he’s off on a business trip. Then, I had one of the smarter thoughts I’ve had in my life: “If I just take this money and write the script, I’ll live off it for a year or so and then I’ll have another unproduced screenplay to toss in the drawer with the others.” So, I bought a video camera and I started to make the documentary that became Vinyl. I haven’t looked ahead so maybe I’m answering the question, “How did the film Vinyl come about?”

If you were actually asking literally about the music that made me who I am, my first four albums, purchased from the Columbia Record Club were High Tide and Green Grass, The Best of The Animals, The Byrd’s Greatest Hits, and Sunshine Superman.

Andrew:

Before you began your career as a filmmaker, you were a taxi cab driver for fifteen years, right? How have those experiences shaped you as a filmmaker? What led to you pursuing film as a career?

Alan:

Ah, see, I half answered that already. It’s true I drove cab for fifteen years but it’s not like I did it before I started making films. I started driving cab after the first time I came back from India. And I did it because I’m a self-indulgent son of a bitch and I was pretty sure I wouldn’t thrive in a job where I had a boss. Then I went to India again because I didn’t know what to do. That was when I broke my parents’ hearts by turning down law school for the second time.

The second time I came back from India, I started to drive cab again to put myself through film school. After that, I was trying to be a filmmaker, but still mostly driving cab. I also drove on movies. I drove Big Bird, Tony Curtis, Scott Baio. Scatman Crothers took me out for dinner on my birthday one year. Scott Baio’s father tried to have me fired and when the production company wouldn’t do it, he got them to issue me a restraining order. I wasn’t allowed to come within 100 yards of Scott Baio. Not many can say that.

Like I said above, I didn’t really pursue filmmaking as a career. I went to film school and fell in love with the idea of being a filmmaker, but I really never figured out how to have a career. I was trying to make fiction. I managed to make a few short films. I taught myself to write screenplays. I had a few scripts sold to TV shows. I wrote a pretty funny line of dialogue for Mr T. And I drove cab, so I didn’t have to quit my fantasy and get a real job. But I didn’t feel like a real filmmaker. I was just a wannabe.

Then I made Vinyl and it came out, and the reception at that first film festival in Toronto was like one of those moments when you start seeing clues that your life just changed. And though I had not been interested in making documentaries, that film opened the documentary door for me and I decided I would be stupid not to walk through it.

Andrew:

In 2000, you put out Vinyl, which more or less gave us a deep look into what drove people to pursue record collecting. That was released 21 years ago. At the time, vinyl was a medium left for dead. What led you to dig into that particular topic at that time, aside from your own love for it?

Alan:

It’s cool the way I keep anticipating your questions. But I don’t know if I can answer this one. For every film you make, eventually someone asks, “Why did you make this film?” And I know they don’t want this answer, but I always want to say, “Because the ten previous ideas were rejected.” That’s part of the answer always. But if you’re asking why I started making the film – 26 years ago – that became Vinyl, I’d say this: I bought records from the time I was a kid; I always had more than most of my friends. I always thought music was important to me, but for a long time, that was like having a hundred records when your friends have 15. Then in my mid thirties, I discovered used record stores. Don’t ask me how I’d ignored them up till then. That was when I really got into records.

That was the late eighties, so by the nineties, these record stores and the people I met there, were a big part of my life and I just started to notice that I never saw a film where someone went into a used record store or had a lot of records. And if you ask, “What about High Fidelity?,” well, I got the money to make Vinyl in 1994, the year before that book was published, not that I knew about the book anyway. I did hear about the film when it came out in 2000, but I had finished my film the year before. And it’s not that I thought, “Oh, this is a great idea for a movie,” I just got a little money, not enough to make a film, but too much to ignore it and I figured, “They won’t care if I make a documentary instead of a fiction film, so let’s see what happens here.”

I would also say that at least half the documentaries I’ve made have not been good ideas. I won’t say they were bad ideas but to me a good idea is one where you tell it to someone and they go, “Oh I’d like to see that.” Good ideas are ones that already sort of have a story and you just have to tell it well. Most of the films I’ve made have been totally blank slates. But that sort of became my thing.

As far as it being a medium left for dead, it’s true that I did make that film just around the time I gave in and bought a CD player but otherwise – and I’m sure most record collectors will say the same thing – my record obsession had no relationship to the dominant culture, if we can call it that. I liked records when they were “alive” and I still liked them when they were supposedly dead. And even when they were alive, the ones I was buying were old and dusty and in a box on the floor. You’re not in the thrift store digging through crap because vinyl is the cool thing to own. You’re in a thrift store and you’re looking through 78s even though you have nothing to play it on and then you spy an 8-track and you never had an 8-track player yourself, but it’s just funny to see a Lou Reed record on 8-track and ultimately the only way you can acknowledge that moment is to buy the darn thing and leave it on your desk.

This is a bit of a stretch, but I saw this documentary called California Typewriter which was about a typewriter repair shop that was still operating, and it was also about the people who still use typewriters, including some celebrities. Talk about the inconvenience of physical media. Talk about a medium left for dead.

Andrew:

Digging a bit deeper into Vinyl. I think, and I admit this is in hindsight, that the film really is even more interesting today knowing what we know now. In 2000, none of us had any reason to assume vinyl would boom again. So, at the time it must have seemed like a case study into a small subset of people clinging to a dying “thing.” Kind of a deep dive into a fledging neurosis. That said, looking back, given the resurgence, it could be seen in an entirely different light, right? Can you expand? Looking back, what are your thoughts?

Alan:

Didn’t I just answer that question? Like I say, I don’t think record collectors are sufficiently connected to the dominant culture to feel like they’re clinging to anything. “People are dumping their records to buy CDs? Great, more for me”. You go with your friends into the thrift store, some go for the old bikes, some for the books, some for the clothes, and your friends know you’ll be looking to see if they have any records, even though you know that it’s probably going to be the same old crap.

There might be some record collectors who are actively aware that they’re “clinging to a dying thing” and some that even think that makes them more cool, that it makes them more interesting that they’re into this thing most other people aren’t into. For me, it never felt that way and that was because the dominant culture was something I was part of and apart from, in all kinds of ways. I never developed a taste for beer. I lost track of my teams for a few years and when I turned on the hockey game and didn’t recognize anyone, I stopped watching sports. I had an old car when I had a car. I got a couple of gigs and actually had a better-than-average year this time when people were talking about a recession. You could conjecture though that the whole dying medium thing is one of the factors that made some record collectors more obsessive. I’m not sure how to explain that. But it might be that the harder you have to look for something, the more your attachment grows.

I think you’re going to ask me something about this later but I will just say that when I started to make Vinyl and met more collectors, I began to see how obsessive it could get. You meet someone in a used record store, and you don’t know what they have back home. And there’s the whole thing of, “No one knows what goes on behind closed doors.”

That’s one of the things I like about making documentaries.

But I think it’s fair to surmise that “physical media” of any kind are more likely to lend themselves to obsession than things that are streamed or on the cloud or in the little chips that are going to enter your body through the vaccine, but like I say, that’s for another day.

Andrew:

On the subject of the “vinyl resurgence,” while I love vinyl, I think it should be taken with a grain of salt, seeing as vinyl sales are only a drop in the bucket compared to streaming sales (which don’t pay, but that’s an entirely different conversation). What are your feelings on the “vinyl resurgence?”

Alan:

The vinyl resurgence has nothing to do with me. The biggest role it played in my life was I got interviewed on the subject on the radio and people started telling me I should make a sequel to my film Vinyl, now that there was this resurgence.

Which is not why I am making a sequel of sorts.

I say it doesn’t have anything to do with me, but as far as things that have nothing to do with me go, I do think it’s kind of cool. I’m glad young people are discovering records. I’m glad that records are being pressed. I’m glad it’s helping some used record stores stay in business. And more than that, I think records are a beautiful medium and if this resurgence is just the media concocting some very exaggerated story because it’s fun to write about, that’s okay with me because as fake news stories go, it’s one of the more fun and harmless ones.

Andrew:

In your original film, a big part of the was the film is stylized is through “confessions.” At the time, you felt vinyl prevented you from fulfilling your dreams of starting a family. What are your thoughts on that through the lens of 2021?

Alan:

Those confessions made my career. I did them in two more films that came to be known as “the mirror trilogy.” Then I stopped doing them and thought I would never do them again so directly. But I couldn’t make this sequel without getting out the old mirror again. I’m not sure what you’re asking me though. But I’ll answer anyway. One, when I started my first documentary and I recognized that it was a pretty personal subject, I started to wonder if there was a way that my story could be a part of the film. Could I be one of the subjects in my own film?

I was into a lot of first-person diary-like fiction or semi-fiction. People that talked about their lives, mostly in literature. I wondered could I do that in a documentary. At first, when I was talking about myself on camera – into a mirror – I was almost exclusively talking about record collecting-related subjects. But gradually, I started to feel like maybe it would be more interesting if I talked about everything else. I’m going to leave that there or we’ll be here all day. Was I right to think that? I think people who love movies and are open to storytelling techniques, and I totally loved that I was telling a story about the mice in my apartment in my film about record collecting. And to this day I meet people who ask, “What the hell was that story doing there?” I’ll go with the first group.

Secondly, I could go through the film and maybe prove myself wrong, but I don’t think I ever said directly that the reason I had no wife or children or family or career for that matter was because I was too obsessed with records. I thought there was a connection though. I thought it was part of the picture. And if anything, I think I was underestimating how much they were connected. Obviously, having an obsession with records doesn’t prevent these things from happening because we have way too many examples of happily married men or women with families and careers and a basement full of records. Without trying to be argumentative, I would guess that most couples with one collector, met when they were young and the collector in the family had learned over the years, how to balance the family and the collection. The wives would often tell me, “I know where he is, he’s not out drinking with the boys, he’s home.”

In other words, the collector had been domesticated. And that was a good thing.

I think it’s far less likely that a 45-year-old chronically single record collector with an apartment full of records is going to invite a date over to their apartment and have that person go, “This is exactly what I was looking for.” But then you have to ask how they got to 45 and chronically single. Sometimes you push yourself out of the running even though you’re not aware of it. There’s luck and there’s coincidence but generally I think “you make your bed” even if you aren’t aware you’re doing it. In my case, I believed then and I still believe my obsession with records was one of the things that kept me away from other things that might have helped me get what I wanted. The one criticism of the film that I will wholeheartedly accept is that when I started to think how the records were keeping me from a happier or more balanced life, I tended to project that idea on other single male collectors I ran across and maybe that wasn’t fair.

I’m not doing that anymore. I’m not doing that in my new film.

Records, or the obsession, or the time I spent with them, or the time I spent looking for them, or the time I spent thinking about them weren’t the only things preventing me, like I say. And they didn’t prevent me from getting lucky and meeting someone late in life who wanted to have a child with me. But I think there’s some truth in the portrait I painted in that film.

Andrew:

Let’s talk current events a bit. You’re working on a new documentary on vinyl, and I believe it’s called Records, right? So, how will this documentary differ from Vinyl? The funny thing about records, and the entire act of collecting them as whole has changed industry wise, but I don’t think much as changed as far as the habits of real deal collectors. Sure, you’ve got the bandwagoneers and the poseurs, but they’re fairweather. Give us some insight into this new doc, and its direction.

Alan:

So if you don’t mind me saying so, you just did something there that a lot of record collectors do, at least from my experience interviewing more than a hundred of them over the course of my two films. And we’re not the only ones who do this of course. But we tend to create straw men.

“I collect records but I don’t collect them like those straw men over there. The poseurs and the bandwagoneers.“

Record collectors are often afraid of being associated with those guys over there who collect that way which we think is funny or too obsessive or interested in that thing that we don’t care about. And I’m not saying those folks don’t exist, but it’s my experience that more or less, most of the people I’ve met who are into this, are more similar than they’re different.

And also lots of us do little things that the others would find unimaginable.

Most people I interviewed would say they’re not collectors per se, they’re just into the music but they keep all their records in plastic sleeves and they care about the condition of the cover and that makes total sense to me. But it’s also completely foreign to me. I bought a Neil Young record I already had the other day, because the couple that owned it first obviously had this stencil that they used and their names were splashed across the front of the record in a way I’d never seen and I kind of have a thing for records with the owner’s name on it.

Okay, now I’ll answer your question. The first night I showed Vinyl, it was a lovely affair, I was being toasted around town, my photo was on the cover of the weekly entertainment magazine but towards the end of the night, I found out from one of my friends that this group of record collectors in the audience were having a drink together somewhere and they were grumbling and complaining and generally mad at me for making such a negative portrayal of their beloved hobby.

And my answer was that I made a personal film about the way that record collecting fit into my life. I wasn’t making a film for other record collectors. I was trying to make a movie for people that like movies. And I had other answers. For one thing, a lot of other record collectors did like it and they didn’t think the portrait I created was inaccurate. And I’m just not that kind of filmmaker that is going to make a film that glorifies this thing. I remember thinking, “If you want that, other people will do that” and that certainly turned out to be true.

Also, I thought that the film was so full of records and talking about records and seeing records, that there was a lot of stuff about record collectors and a lot of stuff for record collectors to enjoy. And maybe it seemed like I was putting down some of the interview subjects but if so, I was putting myself down too. Basically, I thought I’m not glorifying it and I’m not vilifying it either. I’m just talking about being human, if that’s not too self-aggrandizing.

But, but, but, but…17 or 18 years later, I was hanging out on Facebook in this group called Now Playing which is one of the many groups where people post about the records they’re playing and other people respond. And I think I just got lucky with this group and another group that spun off from it. I think I got lucky with this group of guys and gals that are mostly American. I’ve been in lots of groups since and I’m not putting them down but sometimes you meet your people and sometimes you don’t. These folks were into a lot of the same kinds of records I was into and they were knowledgeable and passionate and I liked the tone of the posts and even the way they could sometimes disagree without getting all huffy about it.

And it’s probably also true that part of the reason this experience was so joyful for me was because I don’t really have anyone to share this with in real life. In any case, one day I realized how happy it was making me to talk about records with these folks and I thought that whether my previous record collecting movie could or could not be described as a bit negative, it couldn’t be described as a celebration of music and record collecting. And here I am, I’m in my late sixties and I do have a daughter now and I do have a career and I’m pretty happy in my life right now and I have to acknowledge that music and records have consistently been the most important art form in my life, for a good half century and what if I try to make a film that acknowledges all that.

I can’t leave that without saying that almost the moment I started making this film, I realized that was probably a really bad idea for a movie. Dysfunction is entertaining, being fucked up is interesting, obsession is a good subject, this happy celebration thing is fine for an internet conversation or a blog post or a YouTube post for your other collector buddies but it may not be a good subject for a movie.

But I made my bed as they say.

Andrew:

What types of characters are you interviewing for Records? An entirely different cast of people, or did you circle back around with any of the same people from Vinyl? What vibe are you shooting for with Records, compared to Vinyl?

Alan:

That’s funny you asked that question about the vibe. I wonder why you ask that and that’s because a number of people I was about to interview for this film asked the same question. And I’d never experienced that before. Sometimes people are nervous and they ask, “What are you going to ask me?” and it’s not that I want to be rude or mysterious or use some technique where I spring questions on them. It’s just that I don’t work that way. I don’t have a list of questions and the only vibe there might be is the vibe you get from me and our conversations and I don’t know how to describe that.

I am being a bit coy here. I think the reason some of the people I was about to interview asked about the vibe or the focus or the angle was because they’d seen Vinyl and they were a bit worried I was going to put them in a film with a bunch of…what word should I use…people a bit on the edge, that they wouldn’t want to be associated with.

But that’s not this film.

So, I didn’t go for any particular vibe but the film is pretty well shot at this point and though it still feels like more or less a blank slate at this point as I get ready to edit it, I guess I could answer it but I’m not sure I want to. But I think I can say that the vibe of the film is a bunch of people who love records talking with someone who loves records and telling that person interesting and entertaining things about their relationship with music and records. Of course that leaves out my role in the film, my confessions, and my mirror pieces. And at this point, I don’t have a clue where I’m going to take that.

People use the word “meta” now. That word didn’t exist when I was making my earlier more personal films. But this is going to be perhaps my most meta film. Records is a film about a guy who made a documentary about record collecting 25 years ago and now he’s trying to make another one.

I definitely could have made this film without even acknowledging that I’d made an earlier one. And I will probably always wonder if I should have done that. And I’ll definitely always wonder if I should have made it without me reappearing in that mirror and blathering on about how I have a daughter now and I’m afraid of dying of COVID and isn’t it weird we can’t go to record stores. But I’m pretty sure I’m going to go through with this and make it clear there’s a connection between this film and the earlier one. In some ways anyway. So yes, there are a few people from Vinyl who reappear, though not the most “out there” people who are either gone or I can’t find them. And it’s not exactly like we’re catching up with those people who were in the other film, it’s just a device to connect the two films. It’s a frame.

Otherwise, like every other film I’ve ever made, I interviewed the people who I came across, who said yes, who came to me through friends or connections or were recommended to me. It was random. That’s the only way I know how to do it.

Andrew:

I’m someone who likes to question things, and I know you’re a record guy, but still, my thought is why now? After the making and subsequent success of Vinyl, what made you want to revisit it again all these years later? Was it the unexpected boom? Did you feel there were things left unsaid? New questions that needed answering? Is there a through line between the two (aside from the obvious)?

Alan:

Oh shit, I think I completely answered this question already. But I’ll answer again. No, it wasn’t the record boom and yes, I felt like there were some things left unsaid.

I’d love to have a conversation someday about all the record collecting movies that have come out after mine. And I do kind of think that mine was the first or close to it. Not that people who made them after me knew about my film. People are still finding it for the first time all the time. But I think I have at least twenty record collecting docs bookmarked on my computer. And there’s a new one I’d like to see about the guy collecting records for Coachella and another one out of Chicago about a dealer and the people who are selling their whole collections. I like a lot of them the same way I sometimes like a music documentary even if I think you’d really have to be a fan of this band to enjoy this documentary.

I guess I’m saying that because I certainly could have left the whole vinyl documentary field to all those people who have come after me. And there was a part of me that thought, “It’s become a pretty crowded field,” why do I need to push my way back in?

But I guess I thought I could bring something to the story. And then there were personal reasons.

Vinyl was my first documentary, and at this point I’ve made ten feature length docs, which is amazing for a guy who thought of himself as a failure ’til almost fifty. And part of me had this romantic idea that though I’m not going to get to make another ten, I should start the next ten by making Vinyl again. Or maybe I wanted some kind of closure. Or maybe, like I said, I wanted to make it clear that even if my record collecting had been part of the picture when I was young and miserable, that still it was a beautiful thing. And there was also this thing where I would read what people say about me, that most of my films had been kind of dark and on the one hand, I would think “not really” and on the other hand, I had to admit that making something a bit dark was no longer such a challenge. Celebration and positivity and sharing love and happiness though, is a big fucking challenge, and at the time I came up with this, I guess I was feeling just self-destructive enough to try and take on that challenge.

That may not be the true answer, there may be something truer buried in my subconscious but that’s that whole challenge thing is probably the biggest part of it for me. I’m not trying to document something that I think the world needs to know. I’m just having conversations with people I relate to and hoping I can make a pleasant 90 minutes for whoever likes my films.

My daughter said I should stop making films about records and make a film about something important. I will if I can just get away with one more.

Andrew:

Let’s talk about the state of the music and vinyl industries a bit. What are a few things you would like to see change for the betterment of both the fans and artists alike?

Alan:

I think you’re asking the wrong person. But I’ll tell you one change I’d like that is probably only going to get worse. I can’t believe how expensive records are. I’m mostly aware of how expensive semi-obscure used Psych record can be but every once in a while I come across evidence of how expensive more recent records can be and it blows my mind.

There was a period of fifteen years or so around the nineties when I was buying newish things on CD and then my CD player broke and somehow CDs went away. And I’m not into replacing CD’s with vinyl. I have one shelf with the records I happened to come across here and there, that were at prices I could afford. A couple of Lambchop records, a Tindersticks, a few Palace or Bonny Prince Billy. But for instance, I had a few Hayden CDs and I’m not in any rush to find the vinyl replacement but then I see that his records are going for 80 bucks or 120. Is that because of scarcity or is that just what they cost? The other day I remembered how much I liked Richard Hawley. I had three of his CDs I think. I looked up one of them on Discogs and it was going for 330 US dollars. Who the hell is going to pay 330 dollars for Richard Hawley? You’re making me go find a CD player and get back into CDs. But maybe there’s an actual reason for these prices. I don’t know. Maybe it costs 300 dollars to make a Richard Hawley record.

But I also hate the price of used records. There’s nothing I can do about it but I often wish that used records would all cost five dollars, with some of the really common ones going for one dollar and the really obscure ones going for twenty. I don’t get how a record store owner puts out a record at fifty dollars and waits for that one person who might come in five years later and pay that. The only time I buy that record is when I have fifty dollars in trade, and I know that’s a false economy and I don’t do it that often. I don’t like the idea that they’re saying this record is “worth” fifty dollars like that popsicle is fifty cents. It’s worth what someone will pay and why don’t you price your records to sell, not what some people have decided they’re worth.

And I can hear how some people would answer that. And my answer to those people would be that sometimes you get to a town and records are priced more or less like I would want them to be priced. Like Detroit. So I know it is possible. Me and my girlfriend were in Detroit two weeks before the lockdown and there were two stores at least where records were priced in such a way that you could take a chance on a record. And there’s a great store I’m sure some of you know in Ithaca. But in Toronto where I live, records are too expensive for it to be fun. It’s like one of my interview subjects said, “There’s only one record store left in the world. And that store is Discogs.” When they look up online what the record is going for, I sometimes just walk out in protest.

Andrew:

How about QC? A lot of people take issue with warped records, misaligned spindle holes, cheap packaging and more. Do you think its as bad as it’s made out to be by some?

Alan:

What is QC? And are you talking about new records? If so, I am not qualified to answer. I don’t mind cheap packaging as long as the record isn’t too expensive.

Andrew:

Record Store Day. I have my opinions on this, which I’ve documented. Some love it. Some hate it. What are your feelings on RSD?

Alan:

You know that thing when a new series is streaming on Netflix or something and everywhere you go, you hear people talking about “making of a murderer” or “tiger lady” or that one about the Rajneesh cult, whatever that was called, and you haven’t been watching it and maybe you don’t have Netflix yet and you just kind of ignore it because the conversation moves on, but one day finally you ask people, “What the hell are you people talking about tiger lady?”

Well that’s how I was with Record Store Day for the first I don’t know how many years. I kept hearing people talk or write about it and I wondered what they were talking about. Then for a while I had my own idea what it must mean, but it turned out I was wrong. I think I heard about it at least five years after it started, and the first time I looked at the list of records was maybe five years ago and I’ve never gone to a store on RSD but once or twice I’ve gone to a store the next day to see if they still had copies of one of them.

I don’t know if it’s a good thing or a bad thing. I tend to think that things like this which say “This is the day that everyone buys records” is not a great thing. But on the other hand, I have occasionally seen a list of things that are coming out and I’ve been pleasantly surprised at some of the older records that were getting reissued.

Andrew:

I’m friends with a few local shop owners, and I’ve come to find that there is a big issue with the distribution stage of records. The end result is online sellers pumping records out below market value (effectively selling at a loss) and making the indie shops look like price gougers. Do you have an opinion on this pretty major issue small shops are facing? I feel the 35-40 dollar single LP trend is BS. Agree or disagree and why?

Alan:

I don’t buy new records. Almost never. Only reissues. I don’t have an opinion. I don’t fully understand the question. Which is good, because when I think I do understand the question it takes me a page to answer it.

Andrew:

What are a few albums that mean the most you and why?

Alan:

I hate lists. I hate the, “what’s your favorite” question. I will mention a few old used records that I bought in the last couple of years. Shaun Harris. He was in the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band. He did this solo record a couple of years after they broke up. There are a couple of cuts that are probably Psychedelic but mostly I’d call it a string-drenched Pop record sort of in the vein of early Nilsson. That sort of quirky Pop record is a genre I love. And the day I saw this record, I just had the feeling that if I hadn’t seen it that day, I would never see it again and I’d never buy it or even know that it existed. At the same store, on the same day I found a record called This Is Siller’s Picture by a guy named Bob Siller. I have to think the Siller and the Harris record were owned by the same person because they are very similar sounding records. I like both records because they’re up my alley and then I like them a bit more because, like I said, I just feel like that day I was in the right place at the right time and otherwise I would never have had the privilege of playing or owning them. Nobody is talking about these records or writing about them or telling you about them, though when I put it up on Now Playing or that other group I belong to, a lot of people knew it and were looking for it and would have been happy to take it off my hands. None of them however knew about the Bob Siller record.

Another one like that is by Rusty Kershaw called Cajun in Blues Country. Usually, I buy records by artists that are entirely unfamiliar to me. But sometimes I can’t find such a record and I think maybe I’ll buy something by one of those artists who I generally skip over because I think I know what their records will sound like. It was in that spirit that one day I bought a Doug Kershaw record. I’d seen him live back in the day, and I thought I knew what his records sounded like. And that Cajun thing I was avoiding turned out to be, in fact, a lot of what he did, but the first record of his that I bought, gave me the feeling that in the sixties Doug Kershaw had been caught up like others in the spirit of the time and he took a few chances, experimented a little, even got a little Psychedelic. And that whole mixing of genres thing is a big draw. I liked the record way more than I thought I would, so I ended up buying a couple more from that period.

If I hadn’t had Doug on my radar, I probably would have passed right by this record by his brother Rusty. When I mention his name now, people often recognize it as the guy who helped Neil Young make one of my favorite records, On The Beach. Actually, there’s a really cool article about Rusty and Neil making that record and it was really nice to read about it, after I had bought the Rusty record. But when I saw the name on the record, I knew he was Doug’s brother and that when they were younger they had a Country music duo as Rusty and Doug or Doug and Rusty or the Kershaw Brothers. And I liked the title. It promised to mix Blues and Cajun music. So, I picked up the record without knowing much more than that and the second cut on side one more or less blew my mind.

I could go on but I’ll leave it there.

Andrew:

Who are some of your favorite artists? Ones that mean the most to you.

Alan:

So many. Neil Young, Curtis Mayfield, Tony Joe White, John Hartford, Ike and Tina, Ronnie Lane, The Staple Singers, Television, Matthew Sweet’s Girlfriend record, The Schramms, The Feelies, Lou Reed, the Velvet Underground, Captain Beefheart, Howlin’ Wolf, The Gun Club, Muddy Waters, Blind Al Wilson, Judee Sill, Earth Opera, Country Joe, Tim Hardin, Fred Neil, Duncan Browne, Fairport Convention, HP Lovecrat, kRichard Thompson…I’m trying to do this off the top of my head so I won’t name every one…Tony Bennett, Scott Walker, Robert Wyatt, Link Wray, the Louvin Brothers, Merle Haggard, The Byrds, The Kinks, Dylan, John Coltrane, Jackie McLean, Art Pepper…I’ll stop soon…Al Green, American Music Club, Smog, Lambchop, Will Oldham, Eric Burdon, Donovan, Aretha Franklin, Blue Sky Boys, Blues Project, Paul Butterfield, David Ackles.

I better stop

Andrew:

Last question. You’ve maintained a strong DIY approach throughout your career, which is great. That said, what advice would you have for young artists of all types just starting out? How does anyone stay afloat in a world that seems to be so abhorrent to creatives?

Alan:

I try to talk people out of going into the arts. I have a whole prepared speech which I won’t recount in full but it goes something like this. You’re 25 and your friends are in medical school or law school, you’re going to the same parties and you’re all together, just starting out and struggling. But ten years later, they will be kind of established and you will still be struggling. And ten years after that, you’re all 45 and they are comfortable in their nice house with growing children and at that age, you could easily still be struggling. And you’ll come to a party in one of their big houses, and they’ll all tell you how they admire you for sticking to your guns, you didn’t give up and wasn’t it cool when they all came to that short film program at the film festival and you were up there on stage with your short film. And you just want to scream that you would trade lives with them in a second to be able to wake up just one morning and not worrying about paying the rent. They’re looking forward to retirement and you’re still waiting for your career to begin.

If I say that to someone and they quit, that’s a win. If I say that and they say, “That won’t be me,” then there’s nothing you can do about them. And that’s not to say “those are the ones that will succeed” because most of them won’t. But those are the ones that are committed. It’s like one of my friends once said in one of my films: “If you could know at 25 what you’ll know at 45, there would be no artists.”

I do have to take issue with your reference to a world that is abhorrent to creatives. I feel like some version of, well not my father because my father wasn’t so against this. My father, the accountant was actually responsible, indirectly, for me and my younger brother going into creative pursuits. My little brother plays guitar with the band that backs Burton Cummings of the Guess Who when he plays live. But anyway I think there’s way too many people trying to be artists or wanting to do a job because it’s creative and there’s definitely way too many of us for the world to support and I kind of don’t blame people for not really caring that we’re struggling. Artists who succeed are way way overpaid and the rest of us pick up the crumbs. And that’s how it should be because this job of mine is way easier than delivering cases of Coca Cola which I quit after three days when I was 16.

Interested in diving deeper into the work of Alan Zweig? Check out the link below:

Dig this interview? Check out the full archives of Vinyl Writer Interviews, by Andrew Daly, here: www.vinylwritermusic.com/interview