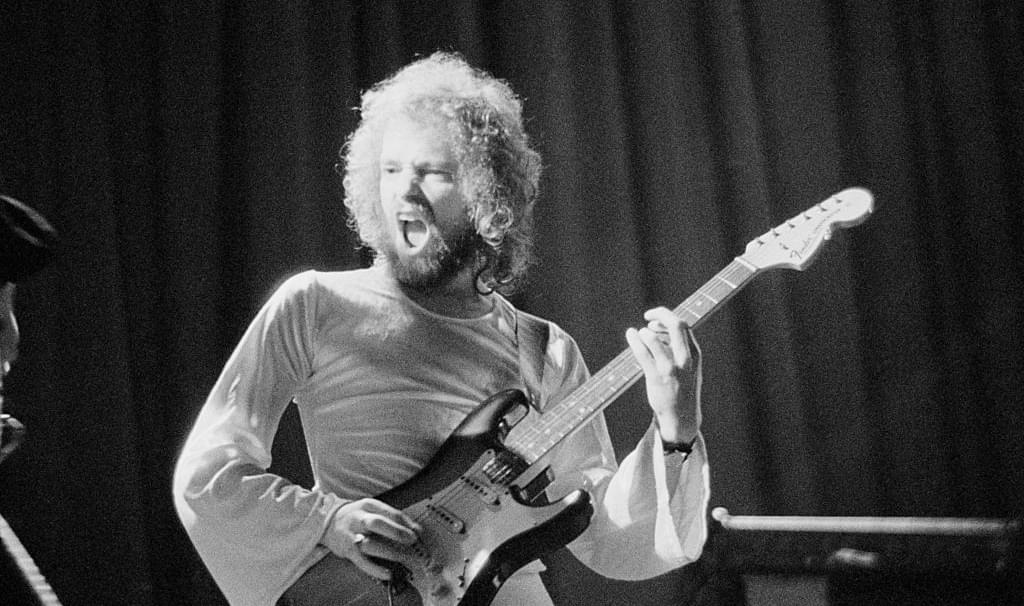

Feature image courtesy of Eric Bell

By Andrew DiCecco

Despite his status as a local legend in Belfast who played with notable acts such as Shades of Blue, The Dreams, and the final iteration of Them to feature Van Morrison, Eric Bell drifted aimlessly from band to band in the late 1960s.

Whether it was an uncompromising vision or a refusal to conform, the enigmatic guitarist never stayed long enough with one band to leave his mark. Additionally, Bell’s varied resume also included a slew of day jobs, further demonstrating his nomadic impulse.

But as fate would have it, on one December night in 1969, Bell would parlay his departure from The Dreams into co-founding one of rock ‘n’ roll’s most revered acts, Thin Lizzy, with singer Phil Lynott, drummer Brian Downey, and keyboardist Eric Wrixon at the Countdown Club in the Dublin.

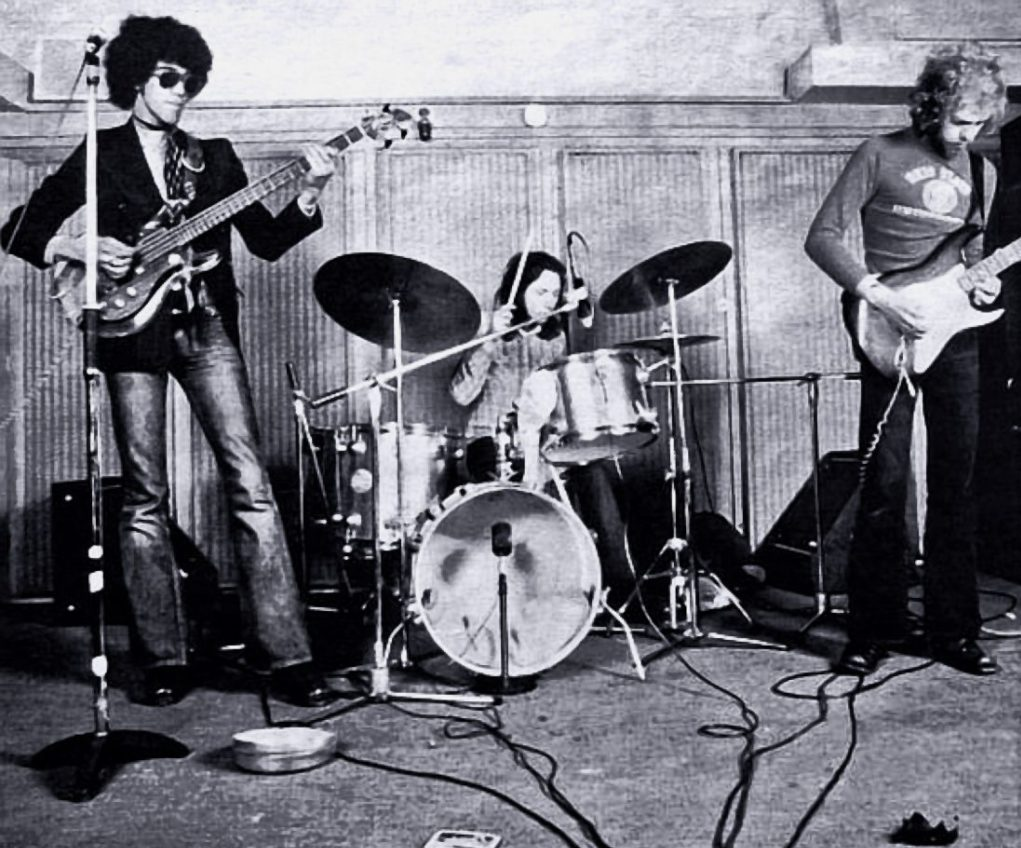

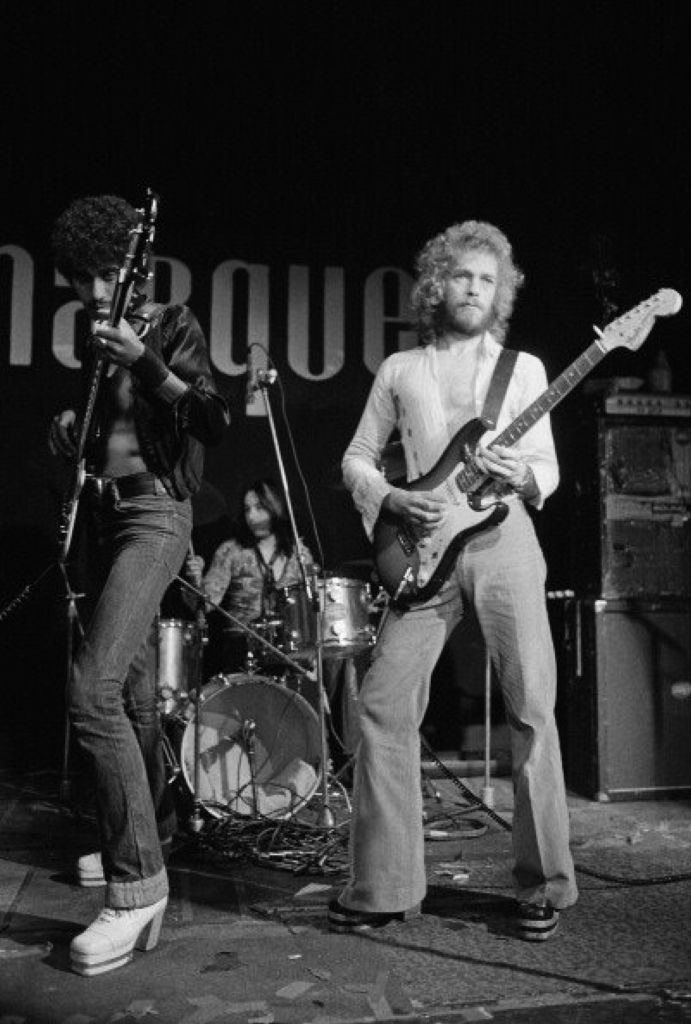

The band would subsequently downsize and become a spellbinding three-piece during its formative years, with Lynott, Downey, and Bell appearing on the band’s first three albums, Thin Lizzy (1971), Shades of a Blue Orphanage (1972), and Vagabonds of the Western World (1973).

A common theme running through Bell’s career, his stay in Thin Lizzy did not last long. However, his distinct influence will forever contribute to Thin Lizzy’s eternal legacy.

From his home in Northern Ireland, Bell recently spoke with me over the phone, where we discussed, among other topics, the genesis of Thin Lizzy and his impact, Metallica’s rendition of “Whiskey in the Jar,” his unorthodox departure from the band, and the ensuing aftermath.

Andrew:

I appreciate you setting aside some time to speak with me today, Eric. To start, let’s go back to the beginning. How do you recall your initial introduction to music?

Eric:

Pretty weird. All we had was a huge, old-fashioned radio, and it was on nearly all day, every day. A lot of it was classical music, and I found, when I was a kid, that classical music would really feed my imagination. I’d be lying on my couch in the front room, and the radio would be on, and this classical music – there’d be pieces of that playing for a good twenty minutes nonstop – and I would be in a different world hearing this music. That’s when I first started getting interested in music. Then you would have some corny stuff – American stuff – like, “How Much is that Doggie in the Window?” That type of stuff would be playing, as well. But even though it was square, some of the music, I still enjoyed it. It was just the very fact of having this big, wooden old-fashioned radio. In fact, whenever it broke – I remember this – I went down to the bottom of the yard, where they put it, and the back part of the radio was a little bit open. I swear to God, I thought I was gonna see little men on horses and things coming out of the back of the radio, being a six-year-old. And all I could see is valves and things like that. It just fed my imagination, that big box in the room.

Andrew:

Your incarnation of the Belfast-based rock group Them happened to be the last to feature Van Morrison. What was the connection there?

Eric:

Well, everybody thinks I played with Them; I didn’t. I didn’t actually play with Them. I didn’t play with the original Them. But what happened was, the original Them formed in Belfast, and they got a record contract with Decca Records in London. They were the host band in Belfast, at the Maritime Hotel, and a scout came over and saw them. They were making a bit of a name for themselves around Ireland, so they went off to England – they had a hit record with “Baby Please Don’t Go” and “Here Comes the Night” – then they split up, came back to Belfast, and went their separate ways. So, Van Morrison formed another Them with a different lineup, and they went to America and stayed in America for a while; did tours with The Doors, Captain Beefheart, and all this type of stuff, then they came back to Belfast and split up. That’s when I first met Van Morrison.

He came into the local music shop and was looking for musicians, and someone pointed me out to him. He came over and said, “Are you Eric Bell?” I said, “Yeah.” I was about sixteen, or seventeen at this time. He said, “I’m Van Morrison.” I said, “Yeah, I know who you are.” He said, “What are you doing tonight?” And I said, “Not a lot.” [Van said] “Do you know where Hyndford Street is?” Well, Hyndford Street was about a twenty-minute walk from my house. So, he gave me the number of the house … “Can you come up tonight at eight o’clock? Bring your guitar.” I was sort of starstruck, ‘cause this guy was pretty famous, even at this point in time – in Ireland, anyway.

So, I went up to his house – his mom, dad, and this big dog went out – leaving me and Van in the front room. He had this huge tape recorder – amazing piece of work – and he says, “Okay, I’ve got a few songs, Eric. The first one’s in G, just jam along.” He put it on the tape recorder, and his voice comes out with an acoustic guitar, and I sort of ab-libbed along with it, making things up. Every now and again, they’d go, “Yeah, that’s nice, man.” And that was my audition.

Andrew:

Along with Them, you played in several other bands in the late 1960s, such as Shades of Blue and The Bluebeats, but I’m particularly interested in what led you to join The Dreams, as well as the genesis of Irish showbands.

Eric:

The Irish Showbands had been around for quite a while; I would say from around 1950-to 1955. They were mostly an eight-piece band, with a three-brass section, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums, and a lead singer at the front. They all wore suits and they catered to the masses; they played what songs were in the top-20 at that given time. They would learn most of them and play them, plus a lot of country and western stuff, and “Danny Boy.” Very, very popular. At one point, I would say there would have been about four or five hundred Irish Showbands. They were the big thing at that point, I would say up until around that time that The Beatles started forming and early Rolling Stones. A lot of them were, when I say “old men,” they weren’t old men; some of them were around forty or forty-five years of age. Some of them were very good musicians, but they were playing a lot of corny stuff just to make money.

I was in The Dreams, and we were on six nights a week – every week – come rain or shine. We had Monday night off. So, that shows you how much work there was available in those days for showbands. But what was happening was, the old showbands started to die off, probably because of age; they’re going bald and they’re middle-aged, so they’re not attracting the young ladies into the dance halls, you know? Sort of a change started happening very slowly; young showbands were being formed, like second-generation showbands, and these guys would be around seventeen or eighteen years of age. Most of them were reasonably good-looking; some of them very good musicians. So, that’s what was happening.

I was in Belfast at this point in time, playing with a blues group called Shades of Blue. I was working during the day because I couldn’t make my living as a guitar player, so I was in a factory. I played one night in the Maritime Club with the blues group I was in, and there was a group from Dublin on that night – they were top of the bill – called The Movement. At the end of the night, I was on the stage taking my amplifier down, and the lead singer [John Farrell] from The Movement came over to me. He says, “Do you know a guy called Eric Bell?” I said, “Yeah, I’m Eric Bell.” He said, “What? We’ve been looking for you for months to come down to Dublin to join our group.” I said, “Are you still looking for me?” He said, “This is the last night we’re playing. This is The Movement’s last gig. We go back to Dublin tonight and split up.” And he said, “They’re forming a young, new showband around me, and I’m the lead singer. We’re looking for musicians. I can give you this phone number and this address. In fact, I’ll write to you and let you know what’s happening about the audition.” I said, “Great.”

So, we went our separate ways, and I didn’t hear anything from him. I said, “Oh, well. Fuck it,” and I was getting ready to go out to work the next morning, and this envelope fell onto the carpet from the letterbox. I looked down and saw it was for me. I opened it up, and it was John Farrell, saying, “Hi, Eric. I told you I’d get in touch. If you want to come down to Dublin, you have to meet these two guys outside the athletic store in Belfast City Centre at 12 o’clock on Thursday morning.” So, I had to ask my folks if I could take the day off work and go down to Dublin to try and get this job. And they let me do it. So, I met the two guys outside the athletic store, and this other guy that was with them had this huge Jaguar Mark II car – beautiful, big machine – and he drove me and the other two guys down to Dublin. There were no other musicians outside where the auditions were being held. I saw about 40-45 musicians hanging around — trumpet players, drummers, guitarists, and so on – and I thought that the job was gone at this point in time; but it wasn’t.

So, they called me in … “Who are you? What do you play?” And I said, “Eric Bell. I play guitar.” [They said] “Okay. Come on in here.” Went in, plugged in my amplifier, and away we went. They seemed to like what I did, and at the end of it, this guy came over who was going to be the manager of the showband, Jim Hand, and he said, “Eric, can you stay in Dublin tonight?” I said, “Yeah, but I have no money.” He said, “Great! Alan, give Eric twenty pounds.” And this guy walked over to me with this enormous twenty-pound note that was about five times the size of an English one; it was like a fuckin’ tablecloth. And then he got this other guy to get me a bed and breakfast to stay overnight in Dublin, which I did. Then the next day, someone else called for me and took me to Jim Hand’s office. We all had a talk with Jim Hand, and I got the job. So, about a week later, I left my job and I left Belfast and went down to live in Dublin.

Andrew:

You seemed to have an established habit of continuously changing bands. What was going through your mind at that time?

Eric:

I was always like that. I’ve always been like that all my life, leaving things. I had about thirteen day jobs, and each one was worse than the one before. I used to stay, sometimes for two-and-a-half weeks, and just go up to the boss and say, “I’m leaving,” or I would get fired because I had no interest in the job. I was the same with groups; I would join groups in Belfast and then leave and join another one and leave. It came to a point where I couldn’t get a gig in Belfast because I was so undependable. Nobody would have me because they would say, “You’re gonna leave in a few weeks. What’s the point?”

I was in two other Irish Showbands before The Dreams. The first one was The Blue Beats, a showband from Belfast; that was the day I turned professional. They were based in Glasco, Scotland. I was with that band for about a year, year-and-a-half, and then we broke up. Then I was with another Irish Showband called the Shannon Showband. They were based in Leeds, England. I stayed with them for about a year and was fired for playing blues licks in “Danny Boy.” I stuck around with the singer out of that showband for a while, and then we split up. Then I came back to Belfast and joined the blues group, Shades of Blue. That took me to the offer with the Movement, which led to me going down to Dublin to join the Dreams. The Dreams was an excellent band. All good-looking guys; nice guys to work with; very good musicians. We got paid a weekly wage, which was very good; we stayed in the best hotels; everything was fine.

On Monday nights off, which was nearly every week, I would score a little piece of dope – which was very rare in Dublin, you may guess. I’d score a little bit of hash, and I would sit there with some girl – we’d have a cheap bottle of Sherry, as well – and I’d put on “Are You Experienced” by [Jimi] Hendrix and John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers with Clapton. I’d be listening to this on Monday nights, and the next night, I’d be out playing “Danny Boy.” It was In my gut as far as thinking, “What am I gonna do? Am I gonna stay with this showband or am I gonna leave and form a group?” So, I started saving up some of the money that I earned from the showband every week and put it in the bank, knowing that if I did leave, I would have something to live on for a while. About three months passed, and I said, “Ray, I’ve had enough.” I went up to Jim Hand’s office and I told him I was leaving. He said, “Fuck me! What do you wanna do?” I said, “I’m gonna find a three-piece rock-blues group.” So, he said, “Have you got an agent?” … “No.” “Have you got any gigs?” … “No.” “Have you any musicians?” … “No.” “Have you got transport?” … “No.” And each time he asked me his questions, this guy would be hammering me more into the carpet. I thought, “Jesus, what am I doing? It’s not too late to change my mind here.” But I just said, “No. I’m gonna try and get a group together.” So, he said, “I think you’re making a big mistake, Eric. But if that’s what you wanna do, go ahead.” He gave me a Vox AC30 amplifier as a going-away present, ‘cause I hadn’t even got an amplifier. So, it was a huge risk. I’ve always taken risks in my life, but this was the biggest one.

Andrew:

It was this risk, of course, that led to the formation of Thin Lizzy. What is your memory of how the band came to be?

Eric:

That whole night was very, very strange. It really was, looking back. What happened was, my money started disappearing because I wasn’t working. So, I was in this bar one night called The Bailey, which is in Dublin City Centre, and buying half pints of Guinness now because my money is running low; I’m sitting over the Guinness, making it last. There’s hardly anybody in the bar this particular night, and this guy walks in, and he sees me and comes over. He says, “Eric!” I said, “How are you doing?” This guy was called Eric Wrixon, and he was the original keyboard with Them in Belfast. He was in a showband called Terry and The Trixons, and they were a young showband, as well. He said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Fuck, man. I’ve just left the Dreams about three weeks ago. I’m doing nothing.” [Eric said] “Oh, wow! You’ve left the Dreams? I’m thinking of leaving the Trixons and playing some decent music, as well. What are you doing tonight?” I said, “I’m not doing anything. I came in looking for musicians and it’s fuckin’ emptysville.” He said, “Okay, I’m still with the Trixons. The drinks are on me.”

So, he started buying me a few drinks, and we were talking. Then he said, “Do you fancy going to a club?” And this was about eleven o’clock at night. I said, “Yeah, why not? I’m doing nothing.” There were about eight or nine clubs in the [Dublin] City Centre we could have went to, but for some reason, we just picked the Countdown. So, we ended up going into the Countdown Club and going off to the bar, where they sold cheap Sherry in paper cups. We had a few of them, and then [Eric] said to me, “Have you ever tried LSD?” And I said, “No.” He said, “Do you wanna try some?” I said, “Yeah.” So, he took out this little, tiny tab and he broke it in half and said, “Here you go.” And I took it. About half an hour later, there was bugger-all happening. I thought, “Fuck me. This stuff isn’t very good.”

At that point, this band appeared on stage, and they were called Orphanage. Philip Lynott was the singer, he was at the front. Didn’t play any instrument; just sang. And Brian Downey was the drummer. I had never seen this group before. Everybody sat down on the floor cross-legged and started rolling joints and so on; it was that particular time in history. Suddenly, the acid started kicking in a little bit, and I started watching Brian Downey on the drums. I was like, “Fuck me, man. This guy is amazing.” He was playing this soul-blues and his playing was so mature – he was only about seventeen or eighteen – and I thought, “God almighty, man. I wanna get a drummer like that for my group.”

At some point, they took a break, and they went over to this changing room. The only two that went into the changing room were Philip and Brian. The guitar player and the bass player went up to the bar. So, I got up, and sort of staggered over to the changing room and knocked on the door. [They said] “Come in,” and I walked in, and Philip and Brian said, “Yeah, can we help ya?” I was out of my head at this point in time, walking about like, “What’s going on?” This acid started becoming stronger. I started giggling, and they thought, “Fuck me. This guy is a fuckin’ nutcase. We better get rid of ‘em.” They said, “Are you okay?” I said, “Yeah, it’s my first trip on acid.” They went, “What!? What’s it like?” And I obviously couldn’t explain it, but I eventually got it together enough to say I was looking for a bass player and drummer, and did they know anybody. They sort of said, “What about him?” … “No..” … “What about him?” … “No…” Then Philip said to me, “What bar do you drink in?” I said, “Well, The Bailey.” [He said] “Oh, you don’t wanna go there. That’s where all the showband guys go. You wanna go to a place called The Zodiac.” So, I said, “Right…” He said, “Do you know where The Zodiac is?” I said, “Yeah, it’s just off Grafton Street.” [He said] “Yeah, call in there. There’s usually some group guys hangin’ about.” I said, “Okay.” And I’m just walkin’ out the door when Philip turns around to Brian and says, “Let’s form a group with Eric.” Brian sort of isn’t too keen on this, but he says, “Okay, we’ll give it a go.” So, Philip comes over to me and he says, “We’ll form a group with ya on two conditions; number one, I wanna play the bass guitar, and number two, I would like to try out a few of my own songs.” I said, “Yeah, let’s go for it.”

So, a week later, Philip came up to my flat. I borrowed a reel-to-reel tape recorder from this girl I knew, and Philip put on the tape. There were three songs on it; I think “Dublin” was one of them; I’m not sure about the other two. I sat and listened and thought they were terrific. I thought his voice was terrific, and his lyrics, and the chord sequences, and so on. And that’s how we started.

But that night, whenever I met Philip and Brian at the Countdown Club and they told me that they were gonna form a band with me, I was still with Eric Wrixon that night and we were still both tripping on acid. We went to another club, called Just Charlie’s, and I sort of saw the devil – and spoke to the devil – that night in this club. And this is the night Thin Lizzy formed, so the whole night is very strange. Then me and Eric went back to his flat, and he had some hash, and we had another smoke. I was gone. And that was the night Thin Lizzy started.

Andrew:

In light of the fact that you named the band Thin Lizzy, Eric, what was the inspiration behind the name?

Eric:

It was about our fourth rehearsal, and we were packing up our gear. As we were packing it up, Philip said, “Listen, what are we gonna call the fuckin’ group?” So, everybody started thinking about names – you know, like book titles, film titles – and then I started thinking about kid’s comics. The one thing that stuck out in my head was, in Dublin, they talk differently than they do in the north of Ireland, where I’m from; in Dublin, they don’t pronounce their H’s. So, if you say, “Three,” Dubliners would say, “Tree.” If you say, “Thick,” Dubliners would say, “Tick.” If you say, “Thin,” Dubliners would say, “Tin.”

So, I had this very profound idea of taking the name Tin Lizzie out of The Dandy comic. There was a female robot named Tin Lizzie, and I thought of putting an “H” in and calling it Thin Lizzy. But the Dubliners would still say “Tin.” So, it might stick in their imagination if they said to me, “We’re gonna see Tin Lizzy tonight,” I would say, “No, it’s not Tin Lizzy. It’s Thin Lizzy.” So, they’d have to make an effort to say that word properly, and therefore, it might stick in people’s heads. And that was the whole idea behind it.

Andrew:

Considering your various musical backgrounds, how did the vision come together?

Eric:

The vision was sort of already there. Philip was a very sharp dresser; he would try different outfits and stage clothes and everyday clothes. He was clothes mad; he was obsessed with clothes and the way he looked. So, he would be taking care of himself, looking sort of sharp. I think that Ireland was always very behind the fashion ways, even from England’s standards; the Irish were like farmers with fuckin’ cow shit in their boots. Clothes would come over from London because the kids in Ireland wanted better clothes. So, these clothes would be coming in – probably off the boats – from London. There’d be a few clothes shops in Dublin, and they would be selling these better clothes. So, that’s where we would go and get buckskin jackets, bell-bottom jeans, and really good stage shirts and clothes.

My hair started growing quite wild – I had sort of a natural afro that became larger every week – and Philip obviously had an afro. Brian Downey, he started growing his hair really long. Eric Wrixon had a great stage image; he’d have an ashtray with a joint, and a bottle of Bushmills whiskey, and a glass on top of the keyboard. This image, it just happened.

Andrew:

Are you able to recall the first original song in the Thin Lizzy catalog?

Eric:

We were very, very lucky in lots of respects. I don’t know how or why, but looking back on it all, we were. We’d only been going about six weeks, or two months, when we got this offer from a guy who owned a recording studio in Dublin. He had this amazing record studio in Dublin, and he offered that if we would record one of his songs on the B-side of a single record, he would let us record one of our own songs on the A-side for no charge. So, we went down to his studio – it was a really good little place – and this guy that owned the studio wrote a song, I think it was called “I Need You.” So, he got us to play it, and Philip sang it. We played all the backing instruments and so on. Then on the A-side, there was a song that Philip wrote called “The Farmer.” It was in the style of The Band. Philip was very into The Band at that point in time. So, I think that was the first original song we would have worked on.

Andrew:

How about your first gig as Thin Lizzy, Eric? Do you remember anything about it?

Eric:

Very strange as well. It was in Dublin City Centre, right in the heart of the city. We did support for another group called Purple Pussycat. It was very strange because the lead singer was probably the only other black guy in Dublin apart from Philip, a guy called – believe it or not – Dave Murphy. That was very strange, because the two groups that were on that night, the two lead singers were black guys. Quite strange. I can’t remember the name of the club or the name of the gig, but I think that was the first gig we played.

Then we got this manager who Philip knew, a guy called Terry O’Neill, and he was only about sixteen. He used to get Philip microphones and things, I guess, underneath his coat, and sell them to Philip at a cheap price. He’d come in one day when we were rehearsing – we’d only been rehearsing about three weeks – and he seemed to sense that there was something there in Thin Lizzy, and he decided to try and become our manager and get us gigs. We didn’t see him for a few weeks, then he turned up at the rehearsal one day with this notebook. He says, “I’ve got you about eight gigs – and for very good money.” This guy was a natural on the phone. He knew how to get gigs and how to get good money, and he was sixteen years of age. I remember one of the gigs, we would play down in the country, somewhere in Ireland, and Terry would come along with us just for a night out. We would play the gig, and at the end of the gig – if there was a good crowd – the manager would call you up at the bar and get you a few free drinks. And this night, the manager called us up at the bar and he said, “You’re a good group, lads. You’re very weird.” He said, “I was talking to your manager, Terry O’Neill. Is he here tonight?” And we pointed over to this fuckin’ kid that was sittin’ at a table with a bottle of beer, and he went, “Fuck me, is that Terry O’Neill!? He took me to the cleaners!” Nobody could believe that our manager was so young and so good.

Andrew:

Prior to the band ascending to prominence, were there any early gigs that were particularly memorable?

Eric:

See what was happening was we were playing outside Dublin; we were playing in Dundalk, Drogheda, Belfast, all over the place. What we noticed was, about every six weeks or two months, we would play the same club again, and we would notice a crowd of people outside the club trying to get in. We honestly thought we were on with another band; we didn’t realize that we were causing this to happen. So, we would go on, and I’d say to Philip, “I wonder who we’re on with tonight?” There was nobody else on, just us and a DJ playing records. So, we started very slowly realizing that we were starting to take off a little bit. People were starting to come out and follow us and see what the fuss was about. That’s the only way I can sort of describe it.

Andrew:

What was the timeframe in which Thin Lizzy signed with Decca Records?

Eric:

Again, that was another amazing stroke of luck. Why these things happened, I’ll never know. There was a record scout from Decca Records in London coming over to Dublin to check out the local talent, to see if there was anybody of interest that they could sign. So, this guy called Frank Rodgers came over, who worked for Decca, and one of the people he wanted to see performing was a guy called Ditch Cassidy. Ditch was a white soul singer; very, very good. For some strange reason, his band broke up around that week. I don’t know why, but it did. Ditch got in touch with Philip, me, and Brian Downey, and said, “Listen, I’ve got no band. There’s a guy coming over from Decca to check me out. Can you help me?” And we said, “Yeah.”

So, we all turned up at this club in Dublin City Centre at about two o’clock in the afternoon. It was empty, and we set up our equipment. Ditch turned up, and we went over a few soul R&B songs with him. The scout from Decca Records comes in, along with our manager, and we started backing Ditch, and Ditch sang a few songs. The guy from Decca said, “Yeah, yeah. Really good. Really good.” I told him what happened, but somehow, we were told to go around to the pub that was around the corner, and we’ll see you in half an hour; that’s what our manager told us to do. I don’t know where Ditch went, he might have been talking to the talent scout for a while – I don’t know – but myself, Philip, and Brian ended up in this pub around the corner from the club. About twenty minutes later, our manager plus the Decca scout came in. They sat down, had a drink, and Frank Rodgers said, “I really like Ditch, but I’m very interested in you boys. Would you be interested in recording an album for Decca?” And we were like, “Huh?” It was like, “Fuck, man. What?” Because there were groups in Dublin that had been going for years on just doing the circuit, and that’s all they were doing. And we had been going about three months and we’re fucking getting a record contract with Decca Records. It was bizarre.

Andrew:

And this all transpired after Eric Wrixon had left the band. As it turned out, Eric didn’t stick around for very long. What exactly expedited his departure?

Eric:

There were a few reasons. God love him, he’s passed away – I don’t want to speak ill of the dead – but he was a bit of a lad, you know? Always quite drunk and stoned – well, I suppose we all were – but he wasn’t really into getting better on the keyboards. He was okay, but from the bottom of my heart, I wanted a three-piece band, and Eric Wrixon had joined, and I hadn’t the nerve to tell him, “I don’t want you in the band,” because he had given me my first acid trip and paid for my drinks that night. Whenever Philip and me got a house together, Eric Wrixon ended up living with us, and then one day at rehearsals, our manager came in and said, “Listen, I don’t know what you’re gonna do, but at the moment, the money is pretty tight. And if you wanna keep going, I think you’re gonna have to turn into a three-piece group.” And Eric said, “When do you want me to leave?” That’s what happened.

Again, for some strange reason, once we went into a three-piece group, we became really popular. I don’t know what it was, but that’s what happened. We went to London, and we were blown away. We just couldn’t believe it. We stayed in this bed-and-breakfast somewhere in London – a real seedy place, all these prostitutes and things hanging about – and we would get up every morning and get the train to West Hamstead. Then, a five-minute walk to Decca Studios, which was a beautiful, old-fashioned building. It was really, really nice. We were like three fish out of water because we were in London now. Last week, we were in Dublin, and now we’re in London recording our first album. So, we were all blown away, Plus, the producer, an American guy called Scott English, he had written a few hit records – Hi Ho Silver Lining and Brady – so he had a bit of a name.

The first time we met [Scott], we were just about to record – I remember that morning – and Philip said to me, “Hey Eric, do you think Scott would mind if I rolled a joint?” I said, “Fuck me, man. I don’t know. You better ask him.” So, Philip asks him, “Scott is it okay if we roll a small joint?” And Scott pulled out this drawer, and there was about a pillowcase of grass in it. He said, “Okay, guys. Help yourselves.” And we got fuckin’ bombed, completely. I hardly remember recording the first album; we were just totally stoned out of our heads all day on this grass. It was great; the three of us had a ball. It was fabulous because Scott just let us try whatever we wanted. There’s some producers who say, “No, no. I don’t think that’s gonna work,” or “Why don’t’ you try this?” He just gave us free rein and said, “Go for it.” That’s what it was like.

Andrew:

As far as Phil is concerned, how do you remember him from your perspective, Eric?

Eric:

He definitely had charisma; there’s no doubt about it. Probably because, well one, he was brought up in Dublin, and very, very, very few black people would have lived in Ireland at that point in time. So, that would probably make him feel a bit special, anyway. Plus, he’s a good-looking guy – tall, slim – and always dressed amazingly and always wore clothes that suited him. He had a lovely voice; very soft-spoken, Dublin voice. He was very into poetry, and he loved the Irish mythology – you know, the warriors of Ireland and so on – he was very into all of that. [He had] a lot of energy to take up the bass at such a late stage and write some great bass lines for his songs and write some great lyrics. He was obviously working on it all the time in his own way. He’d carry sort of a gypsy bag with him all the time, with a book and pens for writing lines to write songs from.

You know, if you asked Philip, “What do you want to be? What do you want to do with your life?” … “I want to be rich and famous.” That’s all he said. He worked hard at it. He worked very, very hard at it. You know, there’s a lot of people who talk about what they’re gonna do, but he had the energy and dedication to do it. That was the difference.

Andrew:

Shades of a Blue Orphanage is the most under-discussed album of your tenure. There are moments of brilliance on that record. What about the recording sessions for that album do you remember?

Eric:

Most groups in the world, they form, they write music, they play, they gig – and then comes the very first record that they have to record. A lot of the time, they put, obviously, the best songs on it and also songs that have been played on stage at gigs. So, all of that goes onto the first album most of the time, which will give you quite a strong album. In a way, that’s what happened to us. We recorded our first album, just called Thin Lizzy, and then our management had us out working all the time to cover phone bills in the office and this, that, and the other. So, we were out on the road quite a lot.

A few months pass, and then our manager says to us, “Oh, by the way, do you know you’re recording your second album in three weeks?” We’re like, “What?!” We haven’t got that many songs because we’ve been out on the road playing, which obviously takes up a lot of time, and we hadn’t time to rehearse new songs. So, a lot of the stuff that’s on Shades was made up in the studio, just so that we would have the material to record an album. Especially that track, “I Don’t Want to Forget How to Jive,” that was written and done in about fifteen minutes. Some of the other songs had been played a little bit on stage. I think “Brought Down” we played on stage, and also “Baby Face.” The rest of it, we were looking for material everywhere in the studio; any ideas anybody had.

I’d come up with that – well, Phillip came up with a title; he said, “Eric, I’ve got a great title that’s gonna fuck up the DJs on the radio.” I said, “What’s that?” He says, “The Rise and Dear Demise of the Funky Nomadic Tribes.” So, he wrote that title for the DJs on the radio, and I’d come up with that funky guitar riff intro. So, again, we were working together.

Andrew:

Thin Lizzy’s live staple, “The Rocker,” is my favorite track from the first three albums. What can you tell me about its origins?

Eric:

Whenever myself and Philip got a house together out in Clontarf, outside Dublin, we did that for one reason: so that we could work on our music every day. Just fall out of bed, have a joint and a cup of tea, and start playing music, instead of rehearsing once a week. We had music in our house all the time, so I’d be sitting on the couch with my acoustic guitar just jamming and expressing myself, and now and again, Philip would walk past me and say, “Is that yours?” Meaning, is the music I’m playing my idea, or is it off a famous album? And I’d say, “No, it’s from a Deep Purple album,” or something. And then another time he would walk past me and hear me playing, and say, “Is that yours, Eric?” I’d say, “Yeah.” So, when I said, “Yes, this is my idea,” he would ask me to come down to the lower bedroom. He’d have an acoustic guitar, I would have mine, and we’d sit and work on his songs.

One day, I was messin’ about with “The Rocker,” and I think I got the intro. He heard that and went, “Is that yours?” I said, “Yeah.” So, we go down to the bedroom as usual and we start working on it. I remember quite a long time later we had moved to England – we left Ireland and were living in London – and we were traveling to a gig one day. Philip was in the front seat, and he had his lyric book on the pen, and he was writing something. He passed it back to me, I was in the back seat, and he says, “Hey Eric, I got some lyrics for that song ‘The Rocker.’” And I took the book and I looked at it. I remember, the first few lines that said, “I am your main man if you’re looking for trouble.” He said, “Do you know where I got that from?” I said, “No.” He said, “You know T. Rex? I am your main man.” That’s where he got the idea, “I am your main man.” So, that was the start of “The Rocker” forming. Then I played this very long solo in it.

Andrew:

What was the process of creating that solo?

Eric:

I think we started playing that on stage before we ever recorded it because I remember the day we were in the studio. We played a few tracks, and now we were gonna try “The Rocker.” Philip came over to me and he said, “Hey Eric, what way do you wanna approach this? Do you wanna approach it the way we do live on the stage or do you wanna overdub the solo after we put down the rhythm track?” I said, “No, let’s play it live.” I don’t know, it was just one of those moments whenever you play guitar; sometimes you can get inspired. You really can, there’s no doubt about it. You can experiment at that particular moment. Just go for it. Follow it. Don’t try to change it, just play what’s ahead of you. You know, you can nearly imagine two seconds ahead of you before you’ve played it. Or else you can work out the solo note-for-note, which I have done for various tracks. Like, “Whisky in the Jar” was worked out note-for-note, and probably the “Little Girl in Bloom” solo.

But “The Rocker” was a one-off. I think that was the only take we did. I just went for it, because I said, “This is the way we play on stage, so get rid of all the inhibitions and just go for it.” You know that if you balls it up you can record it again, so why not just go for it? And that’s what we did.

Andrew:

Now, typically, what was your approach to soloing, Eric? Did you map them out before going into the studio or were they mostly spontaneous?

Eric:

No. Some of the solos I would make up in the studio because what was happening was, Philip would go out and put on a different bass line. Most of the time, he’d go out and do his vocals, so that might take half an hour. So, I’d be sitting in the control room in the studio with my Fender Stratocaster up to my ear. As the track was being played, I would have one ear listening to the track being played as Philip is putting on vocals, and my other ear would be on the Fender Stratocaster, trying to think up ideas for the track. So, I’d make up a lot of solos in the studio. Now and again, depending on who was engineering and who was producing, I’d go out and try these ideas.

Andrew:

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the powerful and intricate arrangement for “Whiskey in the Jar.” Your guitar work on that is sublime and incredibly moving. How did that one come together?

Eric:

Well, that was the hardest piece of music I’ve ever worked on in my life. I can say that. What happened was, we went down to record “Black Boys in the Corner” as the A-side for the single for Decca. Then everybody asked us, “Okay, what have you got for the B-side?” And we hadn’t got any particular song at that point, so we were talked into trying “Whiskey in the Jar,” which we didn’t want to do. We said, “Fuck me! Whiskey in the Jar? We left Ireland to get away from this music, and you want us to record it?” Anyway, myself and Philip went with two acoustic guitars and Brian on the drums, and they recorded it.

Then they said, “Eric, what are you gonna do on the guitar?” And I said, “I don’t know. I haven’t a clue.” It’s not rock, it’s not blues, it’s not funk, it’s not soul. I don’t know what it is, and I didn’t know what approach to use because there was an intro, there was a guitar riff, there was a guitar solo – and I didn’t know one note of any of that. So, they gave me a cassette and said, “Will you work on this at home and try and think of something?” I said, “Yeah.” So, I went home, but the thing was, Thin Lizzy, we were playing all the time. Our manager had us everywhere – England, Scotland, Wales – and I’m trying to find the time to arrange this song. Weeks are going past, and I have no idea. Everybody’s asking me: the record company, Philip, the management … “When are you gonna do this fucking song?” So, one night, we’re traveling back from Wales to London – very long drive – and Philip is playing a cassette of that Irish traditional band The Cheifdons, who I thought were amazing. And I suddenly got the idea, “Why don’t I pretend that there’s Irish pipes playing instead of a guitar?” So, of course, that can give you a new way of phrasing, because there’s not a guitar, so you’re gonna be playing different notes in a different order if you use your imagination and think, “No, this is the Irish pipes I’m playing.” That came from the idea of the Irish pipes.

I had it all worked out. I had every note worked out, for the intro, for the riff, for the solo. I thought, “Somebody’s gonna fuckin’ stop me whenever I try this and say, ‘Oh, this doesn’t work.’” So, I went into the studio that day, and everybody had done what they’d done: Philip had sung his part, me and him played the acoustic guitars, and Brian had his drums on. There was no bass. So, they put on the tape, and they said, “Okay, Eric. Let’s see what ya got.” And I was waiting all the time for somebody to say, “Wait a minute. Can you come in and listen to that? I don’t think that’s working.” And every note, they let me play, because it was so worked out. It was like a paint by numbers. Thank God it worked out, ya know? I think that’s why it’s stood the test of time.

For the first time, I think, ever, I was putting on my commercial hat. We didn’t know it was gonna be the A-side at this point in time, but nevertheless, I started thinking, “The Beatles did it (hums intro to “Day Tripper), and the [Rolling] Stones did it (hums intro to “Satisfaction”), and countless others (hums intro to The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me”).” Each one of them has a repetition throughout the whole song. They’ve all got this phase that repeats, and repeats, and repeats the whole way through the song. And that’s the hook. I’d never thought in those terms before, because Thin Lizzy, to me, was not a commercial group; it was sort of a rock/blues trio. So, you know, I never thought in that way, and on this particular day, I did. You know, I started thinking, “Right, why not? You’ve made up this solo, you’ve made up the intro, so come up with something that repeats.” Which is sort of a question-and-answer sort of thing. And that’s how that happened. That was really me thinking, “Repetition. That’s what I want. I want a phase that repeats, sticks in people’s heads, and never fails.”

The riff, that was me sort of humming over and over and over and over again everywhere I went. If I went into the shop to get a packet of cigarettes, if I went to the bar, if I went for a walk in the park, what do I hear? That took a long time, and then the guitar solo took a long time, but I worked it all out. Then they said, “Are you gonna come in and record this?” And I said, “Yeah.” I went in and I played every note that I had been working on, and the whole thing fit, thank God. And it seemed to capture people’s imagination.

Andrew:

How long did it take you to write that solo?

Eric:

I would say about ten days; the start of it, the intro, about three weeks ‘cause it was a piece of music that people would just present to you, which you’d never done before. Once you put in two acoustic guitars, and you’re used to playing blues licks and rock licks, and then this completely different piece of music comes up to you and they say, “What are you gonna do now?” And it took me a long time. I’m glad it took me a long time.

Andrew:

What are your thoughts on Metallica’s interpretation of “Whiskey in the Jar?”

Eric:

Well, that was funny. That was very funny. I’d left Thin Lizzy and had one of my own bands, and I was doing a tour in Sweden at this point. After every gig, people come into the changing room for autographs and a bit of a talk and so on. Every night, some guy would walk in there going, “Hello, Eric. Have you heard Metallica’s version of ‘Whiskey in the Jar?’” And I’d go, “Who?” I had never heard of Metallica, because heavy metal doesn’t interest me, apart from Slipknot. So, each night, these guys were coming in … “Have you heard Metallica…” … “No.” … “They’ve done ‘Whiskey in the Jar.’” … “No, I haven’t heard it.” So, anyway, about ten days later, we’re at the airport waiting to fly back to London. And there’s a little record shop, so I go in and I look under ‘M’ for Metallica, and there’s about five thousand fuckin’ albums. I went, “Fuck me! This is Metallica?” So, that’s all the information I got. But then I looked at one of the sleeves, and it said, “Whiskey in the Jar,” traditional arrangement: Metallica. And I went, “Right…”

So, whenever I got back to London, I phoned Thin Lizzy’s office, and I said, “Can I speak to Chris Morrison?” … “Speaking…” I said, “Chris, Eric Bell here. Listen, there’s a band called Metallica…” … “Yes, yes. We know. Our lawyers are on it at this very moment.” I said, “They’ve put down that it’s their arrangement. It’s not their arrangement, it’s my fuckin’ arrangement. Or Philip, myself, and Brian’s arrangement.” … “Yes, we know.” So, anyway, about six months later, I’m in my flat in London, and the phone rings. He says, “Hi, can I speak to Eric Bell?” I said, “Yes, Eric Bell speaking.” … “Oh, hi, Eric. I work for Metallica. We’re doing a world tour at the moment, and the guys would be very pleased if you could appear with them in Dublin to do ‘Whiskey in the Jar.’” And I said, “Oh, yeah?” He said, “Have you heard Metallica’s version of Whiskey in the Jar?” I said, “No.” … “What planet are you living on, man?!” I said, “Jupiter, where are you?” [Laughs]. So, anyway, I flew over with Metallica to Dublin. They played this theatre called The Point, which holds about 8,000 people, and I played “Whiskey in the Jar” with them on stage.

The funny thing about it is, we got on the plane at Dublin airport, and then flew back to England. As I was getting out of the plane, one of the road managers came over to me with this huge, big ball of merchandise – scarves, t-shirts, belts, badges, and fuckin’ God knows what … “Here ya go, man. Really nice night. Bye!” And they all fucked off and left me with a car that was gonna drive me home, but they hadn’t paid me a penny. So, I was sort of scratching my head going, “Wait a minute. They’ve fucked off and I haven’t been paid!” I was expecting about two grand, you know? ‘Cause these guys are loaded, so two grand wouldn’t mean shit to them. But they didn’t pay me one fucking cent. The whole way home I was sittin’ thinking about this, “What the fuck’s happened? I mean, did they think I was a fan, and they gave me all this merchandise, and that was my fee?” Anyway, I went home, and I told my mother-in-law, who was well on the case for these types of things. She tried to get in touch with Metallica, but we couldn’t find a way to get in touch with them. We couldn’t find any opening to get to them.

Andrew:

Compared to Thin Lizzy’s initial blueprint, Vagabonds of the Western World adopted a considerably heavier sound. How do you explain the distinct sound evolution?

Eric:

Well, it’s very strange, because the first two albums – in fact, the first three albums – whenever we had released them, we couldn’t give them away. Nobody was interested in the albums. None of the press; none of the English press. Apart from Kid Jensen and a little bit of John Peel, we were on our own. We got pretty mediocre write-ups for the three albums, which I thought was very unfair. And sometimes we thought it was because we were Irish that people were putting the boot in, you know? I mean, it’s incredible, because fifty years later, the first three albums are rated stronger than ever these days.

When it came to the third album, we obviously already had two albums under our belt, and I learned from this process. I said, “Because no one took a fucking bit of notice of the first two albums, I’m gonna play as well as I can on the third album. I’m not gonna get stoned too much, or drunk. I’m gonna keep myself together. I’m gonna put new strings on the guitar all the time; I’m gonna check the tuning all the time.” Which I never really bothered with on the first two albums, because the first two albums — I must admit — we were very stoned. You can’t hear things in a different way. On Vagabonds, I made a promise to myself that when I went in there, the first day, I was really gonna really fuckin’ take notice of what was going on, because you suddenly realize that what you’re playing is gonna go down forever. That’s it.

So, when it came to Vagabonds, I said to the engineer, “I’ve got my guitar set up, and the amp, and all the rest of it, and I’ve got a tone I like. Could you record me playing out in the studio for maybe thirty seconds and let me hear it?” He said, “Yeah.” So, he recorded it, and I came in. He put it on, and I thought he’d put on a different fucking tape. And I’m waiting for my playing to come on. I say, “Where’s the one you recorded?” He says, “That’s it, mate.” I said, “What?! Are you fuckin’ jokin’ me, man? That sounds like a heap of shit. Like five fuzz boxes.” I said, “Come outside and I’ll play in front of ya, and you can hear what tone I’m gettin’ out there.” So, he eventually gets up, and he walks out with me. I played, and he said, “Sounds the same to me, mate.” I said, “It’s not the fucking same, mate. It’s much, much cleaner.” So, we went into the control room again and we sat down. I said, “Twiddle a few fuckin’ knobs. Do somethin’.” And I didn’t know whether he was gonna hit me or fuckin’ cry. So, he eventually started fiddling about and I said, “Yeah, yeah. That’s more like it. That’s the sound I’m after.” It was like that nearly the whole way through the album. I had to fight for nearly every note I fucking played, but I wasn’t gonna back down. I said, “No, it’s me that’s on this album. Not you. You’re the fuckin’ engineer, mate. I’m the fuckin’ guy that’s gonna be on this album. Once it’s down there, that’s it.”

So, that obviously changed stuff, and then Philip was experimenting with a lot of different amplifiers. Every time I’d seen him, he had a different bass guitar; he had a see-through Dan Armstrong; he had a Rickenbacker; he had a Gibson at one point; he had an old Fender Precision. And then he tried different bass amps; acoustic amps, Marshalls, whatever was out there. And Brian Downey was taking a lot more time setting his drums up and getting the sound he wanted. So, all this was going on for the Vagabonds album, so I think that’s why it stands out more. Plus, I think Philip’s songwriting was stronger and his lyrics were stronger, as well. To this day, I’m very proud of the three albums, but especially Vagabonds. I think there’s some great ideas on it.

Andrew:

What do you remember of that New Year’s Eve show in ’73 that marked the end of your career with Thin Lizzy?

Eric:

Not very much. [Laughs]. I was fuckin’ peckled. I didn’t know where I was, who I was, what I was supposed to be doing; that was what it was like. They should have canceled the gig. I was a fuckin’ walking basket case; a Keith Richards multiplied by ten type of thing. I walked on stage, and there were about eight hundred people all sitting down. My girlfriend is in the front row, all my cousins from Belfast were in the front row; lots of people I knew were in the audience. We walked on, and I just wasn’t there. For a long time, I had been having trouble with alcohol, and obviously, with drugs. Same old story, except the difference, is when it happened to me, I was twenty-one years of age. A lot of the time, it doesn’t happen to guys ‘til there about forty, and at forty-five they burnout. I burnt out at a very early age; it was just things going on in my private life that weren’t great. I was drinking a lot, I wasn’t eating very well, I wasn’t exercising, smoking a lot. [I was] taking whatever I could get, basically, and I was on Librium from the doctor, so I was taking that as well. So, I was pretty out there.

This particular night, I got to Queen’s University, and nobody had turned up at that point in time. The road managers hadn’t turned up with our equipment, and Philip and Brian were probably still at the hotel. So, I was shown into the changing room. I was on my own. And I had this enormous table in the changing room, covered by a white cloth. When I took the white cloth off, every type of alcohol that’s ever been invented was sitting on that table. I started going, “Oh, for fucks sake, control it, man! Take it easy. You’ve got maybe one or two hours to kill before anybody else turns up.” So, I started having a draft Guinness out of a tin, and I would sit with that for a while, and then I would have a very small whiskey. And then I’d have another very small whiskey. And then I’d have a small whiskey. And then I’d have a small brandy. And fuck me, man; by the time we were going on, I was not there.

I remember walking on stage and – well, I don’t remember walking on stage, actually – I remember standing on stage wondering how I got there. And we started the show. I started playing, and I suddenly started thinking, “Fuck me, what song are we playing? Have I played the solo yet? Are we in the second verse?” And that’s when it started becoming a bit weird. I lost the plot completely. About the fourth number, I didn’t know where I was; I didn’t know what I was playing. I had no idea. It was like somebody else was playing guitar, not me. This voice that we all have inside our head, self-talk – except this one, I think, was on my side – and the voice said, “Listen, mate, you gotta get out of this situation, or you’re fucking dead, or you’re an alcoholic, or you’re a junkie. Take your choice.” You see, I couldn’t make the change I wanted to make while I was still with Thin Lizzy. It was impossible. I remember thinking, “Right, after tonight’s gig, I’m gonna have one Guinness, and then I’m gonna go back to the hotel room and have a fuckin’ nice sleep.” But that never happened. Every show we played, I’d walk off the stage, and the circus would start again in the changing room; loads of drink, loads of dope, blah blah blah. And I enjoyed every minute of it. But there was a part of me that wanted to stop for a while and clean my act up. I couldn’t do it; I didn’t have the willpower at that point in time. I’d just fall into this circus again.

I knew that Philip was starting to get into cocaine a little bit, which I wasn’t; all I was doing was drinking, smoking hash, and taking Librium. [Laughs]. But that night, this voice said, “You gotta get outta here, mate. You gotta get out of this situation. Do you not realize what can happen? You’re gonna fuckin’ do yourself in. You really are.” It’s staring me straight in the face, and I can’t deny it, and I can’t change it. So, I have to get out of this environment. And this voice said – it’s like somebody that’s about to commit suicide, and they’re standing at the very, very edge of a skyscraper; their feet are just over the edge, and they’re thinking to themselves, “All I have to do is lean forward, and it’s over. But am I gonna do it?” Because if you make that choice, there’s no way you can change that choice when you’re flying down towards the fuckin’ earth. And that’s what it was like; this voice said, “What are you gonna do? Are you gonna stay and slowly fuckin’ kill yourself, or are you gonna get out?” And it said, “Get your guitar, throw it up in the air, kick your amplifiers off, and get the fuck out of here.” And that’s what I did; I took the guitar off, I threw it up in the air – I can still see it now, hovering before the descent – and I saw it hit the stage. It’s the one I still play. I walked over to my amplifiers, my two 4 x 12 cabinets, and I just booted them as hard as I could, and they toppled like big boulders. And I just staggered off the stage. There were stairs at the side of the stage, and I just staggered down. Underneath the stage was gymnasium mats, so I just collapsed on top of these gymnasium mats. Our personal roadie, road manager, Frank Murray – he’s gone as well, God love ‘em – he came down and he said, “What the fuck are you doin,’ man? For fucks sake, get up on stage! Finish the gig!” I said, “Man, I’ve left. I can’t do this anymore.”

They got me a few drinks, ‘cause I said I’d go on if they got me a few more drinks, but it must have been horrendous. I think the whole thing came to a head when there were three guys that came in underneath the stage with me, where the gymnasium mats were. They were like eighteen, nineteen years of age, and one of them had a big bottle of lemonade. My throat was like the Sahara Desert, and I said, “Hey, listen, can I have a drink of your lemonade?” He goes, “Yeah, sure!” So, he gives me the lemonade, I take the top off, and I took big gulps, and I realize it’s whiskey – it’s not lemonade. They got it into the gig – you weren’t allowed to drink at the gig – and they smuggled it in. So, I’m taking these gulps, and then suddenly, this whiskey hits my – you know the temples on your head on each side? – it just goes “Baaang!” And that’s me; I’m gone completely. But the road manager comes back with a drink, which I was nearly sick all over ‘em when I seen it. He says, “There’s your drink. Now, c’mon! Get back on that stage!” Honest to Jesus, it must have been horrendous, because no one had re-tuned my guitar. On the Stratocaster, there’s five little springs at the back, and two of them bounced out of the guitar when the guitar hit the stage. So, it was completely out of tune. And they brought me on stage, in that state. I can’t remember anything after that.

Andrew:

And this all took place at Queen’s University?

Eric:

Yes. You know what the most ironic thing about this is, as well? The last night I played with Van Morrison was at Queens University, and that night, I was drunk as well. Very strange. I remember Queens University students were on a rampage and there was lots of wet paint on stage, all different colors, and our feet were sticking to it and so on. Anyway, they had some drinks for us in the changing room, and I had one too many. So, we went on stage- and we’re playing away – and then I see Van saying something to the bass player. The bass player walked over to me, “Listen, Eric, Van says you’re a bit loud. Can you turn down?” So, I turned down, and then I noticed Van turning up his guitar. I had a few drinks in me, you know, Belfast cowboy, and I said, “Right, fuck you.” So, I turned up again. We did the gig, and I wasn’t feeling very good after the drink. It hadn’t a good effect on me that night. All the audience went home, and the four of us are sitting, waiting for taxis to take us home. So, I’m sittin’ there on my own, and I just went over to Van and I said, “Hey, listen, Van, I’m leavin’ the group tonight.” And he just looked at me, put his hand in his pocket, and said, “Here’s your money, man.” And that’s all he said.

Andrew:

In light of the dramatic manner with which your tenure with the band ended, how did you cope with the immediate aftermath?

Eric:

It was horrendous. What happened was, I stayed in my family’s house in Belfast that night, and thank God they were all in bed whenever I got a taxi back from Queens University. It took me about ten minutes to find the keyhole to put the key in the front door. I just couldn’t focus. I remember the house was in darkness; these are very small houses in Belfast in those days, with no central heating and all that type of stuff. So, there was a big fire in the front room where I walked in; everyone’s in bed, and the house is in darkness, except for this big fire. I just sat down in front of the fire, I lit a cigarette, and I just stared at the flames for about a half-an-hour, thinking, “That’s it. You’re out. It’s over.” So, we haven’t got a phone in our house at that point in time, so about two o’clock in the afternoon, there’s someone at the front door. I went out, and it was one of the roadies from Thin Lizzy, and he said, “Right, Eric, Chris Morrison wants to talk to you. He’s gonna phone you from London, so I’m bringing you up to the hotel to take a phone call.” So, I said, “Okay,” and I went up to the hotel, where Philip, Brian, and the road managers were staying.

They were all sitting in the foyer of the hotel when I walked in, and no one would look at me; they just completely ignored me. Road managers, everybody. So, I just sat in a chair on my own, and then I heard this announcement, “Would Mr. Eric Bell please come to the nearest telephone.” I got up, I walked to the telephone and picked it up, and I said, “Hello?” And it was Chris Morrison, our manager, phoning from London. He said, “Is that you, Eric?” … “Yup.” He said, “What the fuck’s going on over there, man?” I said, “Listen, I can’t go on the way it is. I just can’t do it anymore.” He says, “Do you not realize you’re halfway through an Irish tour? You can’t just fuckin’ walk out like that!” I says, “Chris, I told you I’m fuckin’ done, man. I’m finished.” … “Is that your final word?” I said, “Yeah.” … “Okay!” And he slammed his phone down. And they got my mate Gary Moore; Philip and Brian knew Gary very well, and they asked him to finish the rest of the tour. And that was it.

Andrew:

How long did it take you to find your feet between your departure from Thin Lizzy and your next gig, which was with The Noel Redding Band?

Eric:

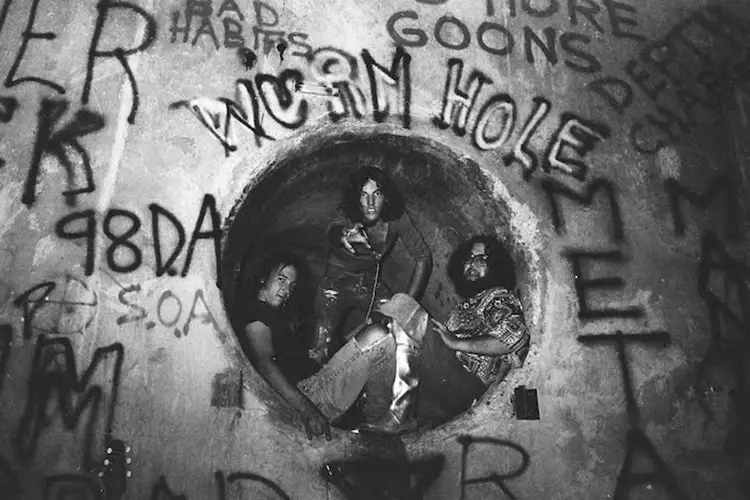

The thing was, in those days, they couldn’t afford to send me to the clinic to get looked after for a week or two. That’s one of the reasons I left. They should have actually booked me into some clinic to get treatment for a few weeks, and then I could join the band again. But they couldn’t afford that luxury in those days; it was just, “Right, you have a gig tomorrow, and a day after, and week after, and a month after.” It was just relentless. After I left Thin Lizzy, one of the things I wanted to do was to get out of London, because London had become a very strange place for me, and I just wanted to get away from it. So, me and my girlfriend left London, and went to Dublin and got a flat. I started living there, and I bought a push bike. I tried to cycle every day and cut down my drinking; dope was virtually impossible to get in Dublin, anyway. So, I formed one or two groups that weren’t great, and one day, about a month later, I got a call from Noel Redding.

He said, “Hello, can I speak to Eric Bell please?” I said, “Yeah, this is Eric speaking.” … “Hello, mate, this is Noel Redding.” And I thought it was one of my mates having a laugh. So, I went, “Yeah, yeah. Of course, it is.” He said, “No, mate. It’s Noel Redding.” I said, “What, from Jimi Hendrix?” … “Yeah.” Out of the frying pan, into the fire, you know? [Laughs]. Anyway, he was living in Cork, in West Ireland, and I was living in Dublin, so he asked me to get the train down so that we could meet. So, I got the train down, and he drove me to his house, and he introduced me to the other guys in the band. Again, it was a four-piece with a keyboard – which I didn’t want – I thought it was gonna be a three-piece, like Hendrix and Cream and people like that. So, that threw me a little bit. And Noel was a very, very obnoxious little fucker. In those days, when I first met him, he hadn’t been long out of Hendrix, so he would be smoking really strong dope and drinking Guinness and cider. Out of his fuckin’ tree in the rehearsal room. And I would have arguments with him about this, that, and the other. He was just obnoxious, but I was a bit starstruck because he was Hendrix’s bass player. So, that’s one of the reasons I stayed.

Then after a while, I started getting back into the drink again. It doesn’t take much to get me drunk, but when I do, I’m not a very nice person. I’m not like that these days, but in those days, I wasn’t a very nice guy. I said to Noel one day, “Listen, man, stuff your fuckin’ group up your arse, man. I ain’t goin.’ I don’t need this. I don’t need to take this fuckin’ shit from you.” Then he asked me to come back, and I went back, and the same thing happened. I just said, “Forget it. It’s not fuckin’ happening, man.” ‘Cause I’d be in the bedroom in his house, just laying on the bed, smokin’ a cigarette and reading a book, and Noel would walk in with the other two guys in the band and say, “Right, Eric, we’re going down to the pub. Come on.” I’d say, “Nah, I’m just gonna relax a bit and read a book.” … “Fuck me! He’s reading a fuckin’ book?!” He would say things like this. And I’d say to myself, “Why the fuck do I take that from this little fucker? Tell him to fuck off!” It was like that all the time, so I left, but by this time, we had management in London. The management phoned me up, “What’s going on between you and Noel, Eric?” I said, “Listen, man, I can’t fuckin’ work with him. He’s on my case all the fuckin’ time. I don’t need it.” … “Right. If I organize a flight for you, and I fly over from London, and Noel drives up from Cork, and we meet at this hotel and sort this out?” And he said, “By the way, it looks like you’ll be doing a tour in America coming up soon.” And I’d never been to America and always wanted to go, so I thought, “Right, maybe I can stick around.”

So, we all met up at this hotel in Cork, and the management was like the referee and me and Noel on either side of him. Robert, the manager, says, “Right, Eric. Now, what do you want to say?” And I say, “Well, Noel is on my fucking case, man, all the time. What are you doing? Reading a fucking book. Blah blah blah.” I said, “I don’t need it. I’ve been through the fuckin’ gates of hell with Thin Lizzy, and I’m not going through them again for fuckin’ nobody.” And Noel just grabbed my hand and said, “Listen, mate. I’m really sorry. I didn’t realize.” We ironed our grievances, and probably six weeks later, we were doing a three-month tour of America; my first time ever. And Noel became one of my best friends. We became really close until he passed away.

Andrew:

If you stayed with Thin Lizzy, Eric, what direction would you have taken the music? Would it have likely remained a three-piece?

Eric:

I would say that it would have remained a three-piece, or maybe another one or two instruments. But definitely not another guitar, because I need a lot of space the way I play. I tried it with two guitars, once upon a time, and unless you have a very sensitive rhythm guitar player, I could live with that. I could live with another guitar player joining, as long as he played rhythm, but very classy rhythm. Something with a bit of class to it, like these R&B rhythm players, you know? They’ve got some amazing ideas for a rhythm guitar, like some chord voicings that very few people use. I could live with that.

I remember when we were in London to record the first album, and we had a night off and Philip said, “Hey, let’s go down to the Lyceum [Ballroom].” So, we ended up going to the Lyceum, which was this ridiculous, hippy, sort of old-fashioned ballroom with balconies and alcoves, and God knows what. It looked amazing, especially just off the boat from Ireland. The three of us went there, we sat on the floor like everybody and rolled a few joints, and the band came on. It was a band called Wishbone Ash, and they had two lead guitars in the band. The only ones I’d ever heard before were the Allman Brothers and probably Captain Beefheart; he had two extremely gifted guitar players in his band. He used them as double lead guitars, as well. Anyway, that night Wishbone Ash came on, and it was two twin lead guitars, and I remember Philip turning around to me at one point and saying, “Hey, Eric, do you fancy getting another guitar player in the band?” I said, “No, Philip, it’s not my style. It works for some people, [but] wouldn’t work for me.” Working on harmonies all the time and you’re stuck playing that harmony piece every friggin’ night you go on wouldn’t be very inspiring to me. I like playing loose on stage; that’s just the way I approach it, you know?

So, I would have kept us a three-piece, and depending on the way that Philip was writing songs – and I would be starting to write songs, as well – you could bring in a guy on keyboards, you could double up on saxophone, or a flute player. It depends on the music. Like, if you’re playing in a heavy metal band, you not gonna have a flute player, or a keyboardist, really. So, depending on the music that you start developing, like, we may have gone into a more jazzy type of music as the years go on. You really don’t wanna be playing “The Rocker” when you’re eighty years of age. [Laughs]. You know, at some point, things would change, the way everything changes. And maybe Philip and I would have said, “Hey, let’s get another one or two instruments in the band, and we can develop a more jazzy approach to the music.”

Andrew:

Thin Lizzy has always featured outstanding guitarists, whether it was you, Gary Moore, Scott Gorham, Brian Robertson, John Sykes, or Snowy White. Do you have a preference or an opinion about who you believe best embodied the foundation that you laid?

Eric:

Me. [Laughs] Well, obviously Gary Moore. Gary Moore was a terrific guitar player and musician, and I knew Gary from way back in Belfast. Way back from the early days, he was always a really shithouse guitar player. The rest of them are good; Scott, Brian, John Sykes, and so on, but I’m not into that type of playing. That type of playing doesn’t interest me in the slightest.

Andrew:

Last one, Eric, and I appreciate you being so generous with your time. Considering the legacy you left with Thin Lizzy, what does that mean to you? How do you see it?

Eric:

With a lot of surprise. Like whenever you’re there at the time, and you have recorded three albums in real-time -and there’s nobody writing anything about it – and all the critics are saying, “Yeah, pretty good lads. Keep at it,” we used to think it was because we were Irish. We really did. You come over to England, and you’re Irish, some people will put you down because you’re Irish. At one point, we started thinking it’s because we’re Irish that nobody seems to have any interest in what we do. But we just worked on and on and worked on and on. I mean, I’m knocked out now, because as I say, of the comments I see of people writing in and giving their comments on the first three albums. It’s really refreshing to see it. You know, it’s really nice. It gives me a real thrill to think, “My God, somebody out there likes what we did.” The other big thing that really knocked me out is, they did a street mural in Belfast. It’s really enormous. Van Morrison’s on it; Gary Moore’s on it; George Best’s on it; I’m on it. I couldn’t believe it. My cousin saw it one day, he’s going past it on this bus, and he saw this enormous, big painting. It’s a beautiful painting, and it’s in East Belfast. And he said, “For fuck’s sake, you’re up there as well!” And I said, “You’re jokin’ me?!” And he said, “No! I’m serious!” Because I didn’t know anything about it; the artist didn’t get in touch with me and say, “I’m gonna put you on a street mural.” So, that’s another thing that’s really knocked me out. Like, big time.

Interested in learning more about the early days of Thin Lizzy? Hit the links below:

Be sure to check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vinylwritermusic.wordpress.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

Leave a Reply