Feature image credit: Stephanie Cabral (courtesy of Harry Cody)

By Andrew DiCecco

[email protected]

Although nearly three decades have passed since Shotgun Messiah was last heard from, the band’s enigmatic, yet multilayered appeal has endured.

Powered by the progressive vision and virtuosic musicianship of vocalist/bassist Tim Skold and guitarist Harry Cody, Shotgun Messiah appeared poised to remedy a waning music scene at the dawn of the 1980s.

Having arrived in Los Angeles via Sweden in 1988, the band, which then included Cody, Skold, drummer Pekka ‘Stixx Galore’ Ollinen, and vocalist Zinny Zan, was determined to forge a path to prominence amid a booming music scene.

After recording their debut album, Welcome to Bop City, under the name “Kingpin” in Sweden, the newly-minted Shotgun Messiah remixed the album in Los Angeles, releasing it as what is now known as their self-titled debut. Released in 1989, Shotgun Messiah produced a pair of hit singles, “Shout It Out,” and “Don’t Care ‘Bout Nothin.’”

The album, brimming with blistering guitar work, showcased Cody’s prowess — particularly on the instrumental “The Explorer” — firmly establishing the newcomer as a household name. It wasn’t long before Cody was being hailed as the next guitar hero.

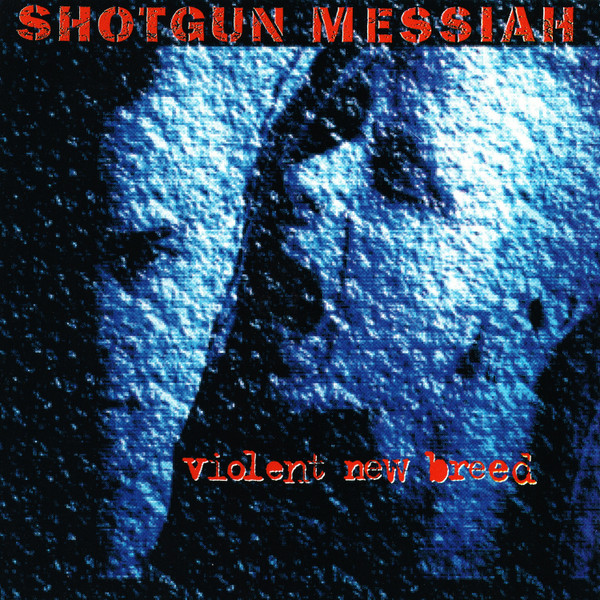

The subsequent follow-up albums, Second Coming (1991) and Violent New Breed (1993), which featured Skold on vocals, were byproducts of the aforementioned enigmatic allure and ever-evolving sound of Shotgun Messiah. While Second Coming departed from the band’s glam metal template established on the self-titled debut, adopting an edgier sound infused with punk sensibility, Violent New Breed introduced an inherently more brutal, industrial metal style.

Though album sales gradually declined as the musical landscape shifted, Second Coming and Violent New Breed offered a glimpse into the future of music, a direct product of Cody and Skold’s influence. Second Coming, of course, delivered such singles as “Heartbreak Blvd.,” perhaps the band’s most well-known track, and the power ballad “Living Without You,” while Violent New Breed produced the anarchic, albeit masterful, title track.

However, as support and interest subsided, Shotgun Messiah — consisting only of Cody and Skold by the Violent New Breed era — would ultimately disband in 1993.

Over the years, Skold remained active as a solo artist, among his various ventures, whereas Cody has maintained a low profile, denying the public the joy of capturing his guitar brilliance.

While younger generations will need to travel back in time in order to discover the tastefulness of Harry Cody’s playing, the wunderkind has left behind a lasting legacy — even if we never hear him play again.

Cody recently broke his silence in this rare, and career-spanning interview.

Andrew:

Harry, thanks so much for taking the time. It’s been quite a while since we’ve heard from you, so first bring us up to speed on what you’ve been up to.

Harry:

Well, lately, the last couple of years, Tim [Skold] and I were thinking about doing a new Shotgun thing, and then, of course, COVID happened. So, that got put on ice, but I’m still working on that. I’m also looking at possibly doing some sort of Patreon thing where I go through all of the Shotgun albums, how I played everything, because one of the things that get brought up the most when people meet me is, “How did you play this? How did you do that?” I might get into that. I’ve been planning it for years, and never gotten around to it, but this time it might actually happen.

Andrew:

I understand you’re also involved in composing television commercials and soundtrack scores?

Harry:

I was. I’ve backed away from that as the money has gotten worse in that business. It used to be that it was really well-paid to do commercials and such. And now, not so much. So, it’s not really worth the effort; you have to answer to a lot of people who know very little about music, but they still feel entitled to an opinion. But I guess they should because they’re holding the purse strings. But still, it’s really difficult to work with people like that, and unless it’s monetarily worth it, I don’t wanna get into it.

Andrew:

So, what’s currently on your docket? In light of the response you’ve received regarding guitar tabs and the clear demand, have you ever tried teaching?

Harry:

No. I’m just fixing my Mac as we speak, practicing guitar, and getting ready for a possible Patreon tutorial of the Shotgun stuff. I have to warm up; some of the songs I haven’t played in decades.

Andrew:

Rewinding a bit to your early days now, to the best of your recollection, what was your earliest introduction to music, and what kindled your passion for guitar?

Harry:

I first started raiding my parent’s collection of singles. They grew up in the 50s and got married in, like, 1960, so it kind of cut off there. So, I got an education in early rock, and then whatever came on the radio in the 70s. I had a huge gap where the 60s didn’t really come into it, but I was a rock ‘n’ roll kid. I was always musical, and I was thinking about getting into piano or something — keyboards seemed interesting to me — but as a working-class family living in a third-floor apartment, we couldn’t really lug a piano; even to rent one would be prohibited. So, we bought an acoustic guitar, and I started fiddling with that and noticed that I had a knack.

Andrew:

Who were some of your most prominent guitar influences?

Harry:

If we skip the very early years when I was kind of eating everything that came my way, be it [Ritchie] Blackmore, or [Tony] Iommi, or Scotty Moore with Elvis, or whatever happened to be on television — Johnny Winter, Chuck Berry — the first time I really, really latched on to guitar players was Alice Cooper, with Dick Wagner and Scott Hunter. Their playing just really appealed to me, and kind of helped shape my style for years to come.

Andrew:

Did you ever have the opportunity to see Alice Cooper live growing up?

Harry:

I did not. Alice Cooper came through Sweden when I was twelve, but my parents would not let me travel down to Gothenburg on my own. It would have been, like, a two-hour train ride, and there was no one to come with me. No one wanted to see Alice Cooper, so I missed out on that, unfortunately. I never got to see them play live, other than on YouTube and such.

Andrew:

During your formative years as a musician, what was a defining moment that influenced you to pursue a career in music?

Harry:

I didn’t have lifelong ambitions at any point, but the very first time I went on stage, I think I had just turned twelve. I went on stage and I played guitar with some other musicians. I was in seventh grade; the other musicians were in ninth grade, I think. It was so incredibly frightening before you do it, and then you get on stage, and I’m thinking to myself, “Oh my God, I just peed my pants.” You couldn’t really tell for sure. But then, when you come off stage, there’s this incredible rush of adrenaline, like, “Oh my God, that was great. I have to do that again.” So, I kind of kept going with that. One good thing that came out if it is, a lot of people have a fear of things like public speaking — they would rather have a root canal without anesthesia than speak in front of people. I have no such fear. I don’t even need a script; you can just shove me out on stage and I’ll be perfectly comfortable speaking to people or playing, or what have you.

Andrew:

As a young performer, that can be an unnerving obstacle, but it lends itself to the captivating stage presence we would later witness with Shotgun Messiah. You delved into music at an early age, but do you have any memory of your first band?

Harry:

Well, my first band was with my brother and one of my cousins on drums. My brother was a bass player, and we called it “Bedlam.” In the early 70s, they played a lot of the old Universal horror movies on television, and Bedlam was a movie with Boris Karloff, so we nicked the title from that, and used it as a band name. It was kind of like supercharged 50s rock; if you imagine playing Chuck Berry songs but plugged into a tube amp that’s screamin’ for mercy. That was our thing, and there was a demand for that, at least locally. So, we did really well.

Andrew:

Describe the music scene in Sweden as you were cutting your teeth as a young musician.

Harry:

The music scene in Sweden was very scattershot. If you wanted to go on tour, you pretty much had to be a dance band, which they played some very European-sounding, Schlager crap. We weren’t that kind of band, so we didn’t have access to those kinds of venues. On Friday mornings, they had these school programs where people came and gave lectures, or entertained or something, and we had ourselves booked that we gave people a twenty-minute shot of rock ‘n’ roll. That kind of garnered our reputation in our hometown and led to more gigs and such. We bought a Ford van and piled into that, and we’d drive to neighboring towns to play gigs.

I didn’t have an amp at the time. I had a crappy Ibanez Les Paul, so the day before a gig, I would always scrounge around town trying to borrow a friend’s guitar, and rent an amp. So, it was a bit of a mess, and I ended up playing a ton of different guitars. I had a Rickenbacker for one gig, and a Yamaha Solid State amp. And the next time, I might have a 50-watt Marshall with a Flying V; something like that. It was always weird combos and really educational. You learn to think on your feet. You have to make whatever gear you have work for you.

Andrew:

I imagine that improvisation would help immensely later in your career.

Harry:

Yeah. And I never had the budget or the patience to get into pedals and such. That was kind of luxury to me. So, I was very much a plug-in-and-play kinda guy. If the guitar has high action and any sound, you just make it work.

Andrew:

Now, what time frame was this, late 1970s?

Harry:

Late 70s into the very early 80s. In the very early 80s, I also did a bit of semi-session work. There were these two local troubadour kinda guys, guitar/singer/songwriters. They had a record deal, and they wanted some local guys to go on tour with them, so myself and my drummer friend, Tord Jacobsson, we went on tour with them. It was another one of those situations where you’re playing a completely different kind of music than you’re used to, and you make it work.

Andrew:

How do you remember your initial meeting with Tim Skold back in 1983?

Harry:

The first time I saw him, his band was opening up for my band, Shinkicker, which was really Bedlam with a name change. But he opened up for us in ’79 or ’80 — he was like thirteen, I think — and he was the bass player/singer in his band. We didn’t really speak, and he was very rough around the edges, but that’s the first time I saw him, and we played on the same bill.

Then a couple of years passed and in 1983, this friend of mine, J.K. Knox he went by professionally — we have the same last name, Kemppainen, but we’re not related — he wanted to start a heavy metal band with me. We were gonna play heavy metal covers, and he had gathered up a drummer, and Tim on bass. So, that’s how we met; we got together, and we just started jamming and called it “Shylock.” We needed a name, and I figured a Shakespeare reference would be a good and obscure enough thing that no one had used the name. I was wrong; there was a Danish or German band already called Shylock, so we had to ditch the name. Nevertheless, that’s how Tim and I first met.

Andrew:

What covers were staples in the Shylock setlist?

Harry:

We played Def Leppard’s “Wasted,” something Judas Priest — I can’t imagine it was “Freewheel Burning,” it must have been something else — I’m gonna have to think on that, “Neon Knights,” and something with Michael Schenker Group: “Armed and Ready.” Some of those songs, and maybe we had Ozzy’s “Over the Mountain” also. I’m just ripping that straight from the memory bank here; I’m not one hundred percent sure.

Andrew:

Kingpin eventually takes shape in 1985, with drummer Pekka ‘Stixx Galore’ Ollinen added to complete the inceptive lineup. Who were some of the early influences that the band drew from?

Harry:

Shylock kept going, and we just went through a revolving door of drummers. It was hard to find someone who was both good and committed, it was usually one or the other, and we bumped into Pekka Ollinen, who I ended up giving the nickname ‘Stixx’ a few years later. It was kind of the same band, but we were developing. We started out as a cover band and we started writing originals in a kind of dungeony, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden kind of format, then it drifted more into Van Halen-ish territory, and then finally, it kind of settled on a hybrid thing that had some elements of Ratt, KIX, and Mötley Crüe in it, which just felt like the way to go for me. I’d heard “Shout at the Devil” and thought, “Yeah, this is where I’d like to take the music, in this kind of more up-tempo, more brutal-but-still-accessible vein.”

Andrew:

You mention Mötley Crüe influencing the musical direction, but did they also serve as a model for Kingpin from an image standpoint?

Harry:

No, there was just a lot of stuff going around. We didn’t have a blueprint. I know a lot of bands, you can look at them and just kind of determine who their influences were, and we were never that kind of band. There were equal parts Sigue Sigue Sputnik — which is terrible synth-punk from England — and they had big mohawks and very, very colorful clothing. It’s kind of like my guitar playing — I don’t consider myself in anyone’s vein as much as I just nick bits, and pieces here, and just kind of make it my own Frankenstein. So, we didn’t have a blueprint for what we wanted to look like. That whole big hair thing, in my mind, originated with Hanoi Rocks, who were more from our neck of the woods, anyway.

Andrew:

How had the Swedish music scene evolved by the mid-1980s? Did Kingpin build any sort of a following through live performances?

Harry:

It was fun, but it wasn’t very career-wise rewarding, because Sweden was on a different track altogether. Dokken was big; Whitesnake; Deep Purple; Rainbow. It’s a whole different kind of hard rock they were into, and they didn’t think much of the kinds of bands that we were more interested in aligning ourselves with. So, there was no real scene for us in Sweden, and that’s what prompted us to move, anyway, because we realized, “We don’t have a future in Sweden with this.”

If you wanna know what the hard rock scene in the mid-80s in Sweden looked like, just look at that — we had like a [Swedish Metal Aid] thing in Sweden, “Give a Helpin’ Hand” or something, with the Europe guys and a bunch of other hard rock alumni from the Swedish scene, and that’s pretty much what hard rock and hard rockers looked like in Sweden. We did not fit in, we would have never been welcome in that kind of a setting, and we wouldn’t have done it even if we had been offered it. We were kind of oddballs in Sweden, so we just tried to make as much ruckus as possible to get a record deal, get a record recorded in Sweden, then come to the states and use that as a demo. We figured that bands walk into record companies with a little demo cassette, and we figured, “Well, we might be up on the deal if we can actually present them a vinyl record with a cover and everything professional.” And that’s what we did. We recorded one album in Sweden, and then, got to the states as soon as we could, and shopped it around.

Andrew:

Did any of the Shylock recordings end up on Welcome to Bop City?

Harry:

Nothing from the Shylock era made it on there. Nothing prior to the switch to the more commercial hard rock format. The first songs I wrote in that commercial vein, that went away from the Sabbathy or Van Haleny vibe, would have been “Don’t Care ‘Bout Nothin’” and “Squeezin’ Teazin’.” I think those were the two first songs I came up with in that vein.

Andrew:

The band decided to transition to a new singer before recording Welcome to Bop City. How did Zinny Zan enter the picture?

Harry:

We were a couple of weeks away from starting to record the album, and our singer came down with throat problems. I think it may have been psychosomatic because every time we had a demo coming up prior to that — we’d been recording demos with some regularity — and every time the studio came up, he developed a throat problem. We’re two weeks away from our big shot — our one shot as far as we knew, from small-town Sweden — so Tim and I just sat down and said, “This is not gonna work. We’re gonna have to think of something else.” So, we had to let him go, went into the studio, and started recording the album without a singer. We brought people to the studio, where they pretty much auditioned on the spot. We took the train up to Stockholm, and spoke to the people who were more familiar with the Stockholm scene, to see if there were any good singers available. Zinny’s name came up, and we were like, “Okay, we know him from Easy Action. Sure, we’ll meet with him.” We got along fine; he’s a super fun guy to be around. So, we brought him down to the studio, he sang on it, and the attitude just seemed right.

Andrew:

What influenced your decision to incorporate the use of copper guitar picks?

Harry:

I used to use the picks that were called Sharkfin. I really liked them, they were really cool, but I went through them like you wouldn’t believe, and it was just getting cost prohibitive to have to go buy plastic picks all the time. This local store had just gotten in a batch of the Hot Licks Cooper Picks, and I tried them out and I just said, “Well, this is interesting. They’re far more durable, and they’re still thin enough.” I don’t like thick picks, so it was kind of a thin pick, but it was sturdy, and I just started playing with them and that was it. It was more necessity than anything; it wasn’t a total choice. It was until later that I noticed all the cool things you can do with copper picks that plastic just won’t.

Andrew:

How did that implementation ultimately help shape your distinct tone?

Harry:

I had one of the original Floyd Rose models of whammy bar before they had fine-tuners ordered straight from Grover Jackson’s garage in Washington State, or wherever the hell he was. Brought one over, put it in a homemade guitar of mine. I didn’t always have a screwdriver handy, so if I wanted to adjust something, I used the copper pick, and that chipped the pick. It got really chipped and eaten up along the side of it, and then I noticed that if I dragged that along the strings — up and down, what have you — then I could make some really cool sound effects with that. And from that point on, there’s no going back to plastic, because there’s nothing you can do with plastic that’s gonna give the same effects. So, like, there’s this sort of ascending ray gun effect at the end of “Trouble” on Second Coming, that is just me swirling the copper pick in a circular motion faster, and faster up the neck. Then, of course, all the scrapes and stuff for “Heartbreak Blvd.” The very last thing on “The Explorer,” before the classical-sounding, free-standing long lick that everyone goes nuts for, it ends with this sound, and that’s also the pick being drawn along the string; from thicker to thinner, just stripped down. So, there were a ton of cool effects that I could do with a chewed-up copper pick that I just couldn’t do without at that point.

Andrew:

To play the way that you did, Harry, obviously required inherent ability, but I imagine it also necessitated a grueling regimen. What was your practice routine like in those days?

Harry:

I started out going on sheer enthusiasm; I just wanted to get better at playing. I’ve never really been disciplined; I’ve always been just as good as I need to be to pull off the stuff I hear in my head. I don’t have any scales that I practice, I don’t have any speed picking exercises; nothing like that. So, I just went on enthusiasm, and then, of course, that enthusiasm got super ramped when Yngwie Malmsteen hit the scene. I managed to give myself tendonitis in my right wrist from just over-picking because it was just so exciting to be able to do that. So, I was just playing until my wrist gave in, and I had to get it in a semi-firm cast for four weeks, I think it was. Then after that, just before the album came out, I knew that the first Shotgun album would be kind of a showcase of what we could do as musicians, and what I could do as a guitarist, so I took it very seriously, and I used Paul Gilbert as my boogeyman. Now, I’m not that familiar with his playing, he was just the hot guy around there — I’d heard some stuff from Racer-X — but whenever I felt like slacking, I thought to myself, “Right now, Paul Gilbert is practicing.” So, that forced me to keep going, so I kind of motivated myself, and then kept it up through the album sessions.

Andrew:

So, the band arrives in Los Angeles in 1988. When you came to the United States, how difficult was it to adjust?

Harry:

Well, we’d grown up with American movies, so it wasn’t that dramatic, but it did feel like stepping into a movie. Swedish grasshoppers don’t sound like American crickets. When Tim and I were staying in Oakwood Apartments up in the Burbank Hills, and at night you’d hear the crickets, we’d be like, “Wow, it sounds just like a western!” There’d be helicopters overhead. In Skövde, if there’s a helicopter in the sky, that means the world’s coming to an end — like something huge has happened — and in Hollywood, of course, that’s routine. There’s always something in the air or sirens going. So, it was interesting. It was like stepping into a movie.

Andrew:

The band was still known as Kingpin when you arrived in the U.S. but had to change its name. How did the name Shotgun Messiah originate?

Harry:

We had a myth-making kind of story back then about how we accidentally bumped upon the name, but the mundane truth of it is that it was suggested by Cliff Cultreri, the vice president of Relativity. We were thinking about new names, and he said, “What about Shotgun Messiah?” And we immediately liked it and we went, “Yeah, that’s a good name.”

Andrew:

Are you able to recount your first gig as Shotgun Messiah?

Harry:

Yes. It was at The Palace in Hollywood, and it was kind of frightening. It’s kind of intimidating coming from small-town Sweden — you know, 35,000 people in our hometown — to playing in Hollywood at The Palace. I think my amp went bye-bye a couple of days before — actually, it might’ve been the day before — so I had to ink a deal with Mesa Boogie really quickly for them to deliver me a rig. I played with an unfamiliar rig — nothing new there, I’d been doing it all my career — but still, it was kind of harrowing.

Andrew:

By the late 1980s, there were many bands of similar style playing around Los Angeles. What was your experience gigging on the circuit in the early days?

Harry:

As far as touring, we never got to see any other bands, because they’d be touring at the same time but they’d be in another town at that point. In Hollywood, there were so many wannabe bands — [ I had] never even heard of Skid Row at that point, they weren’t a west coast band — but all the other usual suspects? Yeah, we saw them. We hung out at the clubs, we saw them play, and just noticed that the level of musicianship wasn’t really all there. A lot of them seemed to be far more interested in being rock stars than being musicians, so we thought we had an automatic advantage in that we actually put equal emphasis on the musician part of it.

Andrew:

Now, did you guys ever establish a residency prior to the release of the first Shotgun album?

Harry:

No. The record company pretty much kept us under wraps. After the gig at The Palace, I think we just went into rehearsals for an upcoming tour. So, we rehearsed at Frank Zappa’s studio, Joe’s Garage it was called, so we were playing there for months before we went on tour. And prior to that, we’d been remixing the Welcome to Bop City album. We did a couple of overdubs, but mainly, it’s the same album as before with some new twists to it.

Andrew:

Your debut album features a sublime instrumental composition, called “The Explorer,” which showcased your prowess. How did that all come together?

Harry:

Well, thank you. It was written specifically for Guitar Player, for their “New Talent” column. I had seen that Yngwie got his career started there, and hopefuls were sending in tapes and stuff. I thought to myself — the same way as the plan with the album, to bring that to record companies instead of a demo tape — I figured that a bunch of guitarists are probably just shredding into a microphone onto a cassette and sending it to Guitar Player. What if I make it a song instead? I’d heard “The Attitude Song” by Steve Vai, and I thought that was a really cool format of doing it, where you could have these wild guitar tricks in a musical context, more like a song. I wasn’t into the whole odd meters and stuff, so mine is much more straightforward. I’m not a fusion guy like Steve Vai — I consider myself a straight-ahead rocker — so I just wrote a rock riff with a lot of breaks or fun fills, and then I just went about cramming it full of all the fun techniques I’d been working up ‘til then. So, there’s a little bit of the sweet picking, and there’s some fast passages, and there’s a whammy bar, and this, that, and the other.

Andrew:

You and Tim did a masterful job from a production standpoint on all three Shotgun albums. Did you have any prior experience as a producer? What did you learn from the experience?

Harry:

No production background other than being pains in the ass whenever the demos were recorded. We’re just really opinionated. The first Shotgun album, it kind of sounds cacophonous now that I listen to it, because our motto then was, “Everything louder than everything else.” So, it’s just kind of making it work. I guess that’s why there aren’t many guitar overdubs; there’s a lot of doubling going on, but there’s just, like, one guitar part, and then there’s a loud bass and there are loud drums, and loud vocals, what have you. And the farthest back is backing vocals. That was really all the production ideas we had. I wanted a trebly bite to the guitar sound, I knew that. I had some run-ins with the engineer on the first album because he dialed up a really nice, ear-friendly sound and I hated it. He threw up his hands and said, “Well, you dial it in.” So, I did the best I could, and there you are.

Andrew:

As the first chapter of Shotgun Messiah closes, the band decides to move on from Zinny, but what influenced the decision to have Tim handle the vocals going forward?

Harry:

We had a few singers lined up that we wanted to try. We had listened to God knows how many tapes, and seen headshots from people who wanted the gig when they heard that the singer gig was open. So, we got flooded with tapes, but no one was really right. There was this one guy that was gonna come down to the studio when we were doing a demo, and he never showed. I just told Tim about this thought that I had for a while, that maybe Tim should take over the lead singer thing, because otherwise, we’d be the bass player-guitar player writing the songs, and then, have to channel them through a third guy, kind of like we did with Zinny. And we were afraid that the Zinny thing would be repeated, where a singer would last one album, then we’d have to get a new one. That would just be a circus. So, I brought it up to Tim that maybe he should give lead singing a try, that way the core of the band would be the singer and guitarist, same as Joe Perry/Steven Tyler, or Mick Jagger/Keith Richards, or Plant/Page, what have you. It’s just a much more stable situation. So, Tim started working on his vocals, and I liked what I heard. He pretty much learned while we were writing, and recording the songs. Then he was ready to go by the time we were on tour.

Andrew:

What was Relativity’s initial reaction to the news?

Harry:

They knew as well as we did in the band that Tim was getting the bulk on the fan mail, even as a bass player. He was the babe of the band, so it made perfect sense from that perspective. After we fired Zinny — that’s not a decision you take lightly after one album, “Yeah, we’re gonna fire our frontman” — usually, that kills a band. But we had no choice, and the label was behind us. Had they not been on board with that, it might have been more difficult. But everyone was on the same page that Zinny needed to go, and I think they were just relieved that Tim would take over duties. If they were sweating, they didn’t show it. I think they were very happy when we finally played them the Second Coming album. As the mixes started to draw to a close, and a few people from the record company showed up and sat down on the couch, and we played it over the big speakers, they seemed pretty damn happy about it.

Andrew:

You and Tim had a creative cohesiveness that evolved with each album. Why do you think the collaboration forged such a strong bond?

Harry:

We are both multi-instrumentalists, and we can do quite well without anyone’s interference, really. It’s just that he and I had — at the time, at least — a very synchronized way of thinking, where we could finish each other’s sentences, and we were on the same page, basically, without discussing things. So, what we did was, I would have the germ of an idea, I would bring it to him and say, “Is there anything you can do to this?” And he would do the same. We still have somewhat distinct styles. If you wanna look at Second Coming, for instance, “SexDrugsRockN’Roll” is one of those songs that Tim brought in. He had the riff, he had everything, I just polished up a few parts, and did some additional lyrics. Then you have a song like “Ride the Storm” or “Living Without You,” which were basically songs that I brought in, where [Tim] collaborated, added parts, did some editing, what have you. So, it’s very collaborative without any friction, really. You mind the other person’s creative ego, because we all do have those, so you just kind of know which lines not to cross, and still let the other one’s creativity show through.

Andrew:

You mentioned bringing in “Living Without You,” a power ballad, which seemingly deviated from the initial Shotgun Messiah formula. Take us through the artistic process, and your frame of mind when you were putting it together.

Harry:

I have a very weird musical mind. I was working on this chorus idea where I figured, “You know what? Usually vocals start on the down-beat, or even before the first down-beat of the chorus. What if I hold out for as long as possible before the vocals even come in?” That lasted about a bar-and-a-half, I think, but still, that seemed like an odd way to do it, and I liked it. Then I thought, “Wouldn’t it be clever to have the first verse sound like your ordinary, typical, sappy ballad, up until the very last line before the chorus?” … “Living without you don’t bother me,” that’s where the twist in the lyric comes in, where you realize, “Oh my God, this is not that kind of ballad. It’s something different.”

Tim helped write the rest of the lyrics — I had the chorus, he helped with the verses — and I had the C-section also, “What good is all your beauty if there’s nothing behind it?” I had that, so I felt those were strong hooks. But I’m very, very proud of, “Don’t flatter yourself.”

Andrew:

I was going to say, that is such a genius lyric! Did you come up with that on the spot?

Harry:

I think so. I had, “If there’s a tear in my eye, it’s not for you,” and then as I was playing it, “Don’t flatter yourself” just naturally came out of that. It’s weird when that happens, where it doesn’t seem like you’re making something up, but you’re tapping into something that should have been there. It’s a very strange feeling, and that was one of those.

Andrew:

Also, the solo is brilliant. It fits the theme and tone of the song perfectly.

Harry:

It’s a song about pain, obviously. Some people see it as some sort of a revenge song — it’s really coming from a place of pain — it’s just not your typical, crying ballad. But it’s still some guy who hurts, and then, you just try to channel that to the solo and you try to figure it out in your head before you ever sit down with a guitar. You try to see where it goes, because the risk as a guitar player is that your fingers do the walking; if you just kind of pick up a guitar and you start noodling, what comes out is whatever your fingers wanted there to be. But if instead, you try to do it by heart, by brain, I think that leads to better solos.

Andrew:

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about the origins of “Heartbreak Blvd.” What do you recall about the creation of a song that ultimately encapsulated the band’s legacy?

Harry:

I was friends with Grover Jackson from Jackson Guitars at the time, and he wanted to introduce me to this guy who built refrigerator-sized amp racks for all of the big players at the time. So, he picked me up in his car; it was me, him, Rowan Robertson from Dio, and Doug Aldrich was already there. And Doug Aldrich was playing some chord structures that just kind of impressed me with how they sounded; they had a very odd and very appealing sound. So, as soon as I got home after that meeting, I was fussing around with chords myself, and that’s how I came up with the main riff for “Heartbreak Blvd.” After the scratching part, when the chords kick in there, that’s kind of what that came from. And the scratching part, it was something I was just fussing around with my copper pick on the guitar between takes, when Tim and I were recording demos up in the apartment. We had a drum machine and a keyboard, and a four-track cassette recorder, and I was just fussing around with the guitar, doing some scrapes and stuff, and Tim said, “You should put that in a song.” So, I just kind of worked out this thing, and I stuck it in front of the song and then I stuck it in front of the choruses, and that was that.

I had been, for years, trying to squeeze in this middle part that now has, “Naa naa” on it. It goes up to G – the song is in E — but it goes up to G. I’d been trying to squeeze that into a song for a long time, so I just kind of forced it in there. We had no idea when he demoed it that that would be the song that would catch on. I had no idea. It’s always kind of a mystery to me what sticks and what doesn’t.

Andrew:

I’m not sure how many appreciate just how incredibly intricate and complex your guitar solos were. Did you ever find it daunting or challenging to replicate any of them in a live setting?

Harry:

Some of them are. There are some of them that would give me a little bit of anxiety before going on stage. Usually the really fast passages. There’s one lick in the middle of “Can’t Fool Me” that is stupid fast and trying to get that clean is kind of a chore. Then there’s another solo from Violent New Breed, “I’m a Gun,” there are some really quick hand movements flying up, and down the neck, that kind of stress me out before the fact. You kind of feel like an athlete; you’re working up the stamina to do it.

Andrew:

Your solo on “Ride the Storm” is brimming with emotion and has become one of my favorites. What was the inspiration behind that particular solo?

Harry:

That was one of the four first songs we wrote when we changed formats in Kingpin. It was “Don’t Care ‘Bout Nothin’,” “Squeezin Teazin,” “Ride the Storm,” and one other song that we never ended up doing, that never got used with Shotgun. So, I had “Ride the Storm,” and I had the solo for years before I recorded it. I think the reason it’s on Second Coming, is really because I wanted to memorialize that solo. I wanted it somewhere because I knew from the get-go that it was a good one; it feels very heartfelt and such. But it wrote itself; it’s one of those things where I pretty much didn’t need a guitar to write it. It just kind of came to me. It seems very obvious to me, the notes, what follows and what doesn’t. It’s a very spontaneous, obvious solo.

Andrew:

Compared to the first album, Second Coming had a distinctively different drum sound. What contributed to the contrast?

Harry:

Well, we listened to a lot of different production things. Tim and I had been into cool-sounding productions, whether or not they had been in the hard rock realm, for a long time before that. So, we knew we wanted to experiment with machine drums, and the sounds of machine drums. Like, you can get so many more cool kicks of everything. So, we knew that to get a good, meaty sound — Stixx played the drums, but he had triggers on the drumheads — and then we ran that to samplers, so that the kick is as he performed it, but the sound was added later. Same thing with the snare. The hi-hats and the crashes were the only things that were real. What you’re hearing is what he played, but everything else is triggered after the fact.

Ironically, that led to a slight time delay between his actual hit; like on the snare, if he hit the snare, there’s a slight time delay between the hit and the trigger firing. So, some of the drums are a little looser sounding — which was not intentional — that’s just how it turned out. Then in the final mix, the guy who mixed the album, he had his own favorite snare sound — like his own sampler that he brought — and he used the signal from the tapes to trigger his own snare sound, which in turn, also had a little bit of a lag time. So, now the snare felt even a little longer behind. So, on something like “Free,” when you listen to the drums, I think the snare lags a little bit. It used to bother me more than it does now, but that was definitely not how we intended it, and it’s not a slight on Stixx’s performance whatsoever. He was as tight as ever, it’s just technical delays on triggers that cause it to sound a little looser.

Andrew:

Before we transition from Second Coming, I have to ask about the album cover. Where was that shot?

Harry:

We went out into the desert, Joshua Tree. I think it was an idea of Tim’s; I know for a fact it wasn’t my idea. But I think Tim wanted a shot out in the desert, so a bunch of us, with a professional photographer, packed into a van and drove out to Joshua Tree. It was really hot. That’s what I remember. [Laughs].

Andrew:

Sandwiched in between Second Coming and Violent New Breed, Shotgun Messiah produced the five-track EP I Want More, featuring covers of The Ramones, The New York Dolls, and The Stooges. Was that done on your own volition, or was that merely fulfilling an obligation to the record company?

Harry:

When we went on tour for Second Coming, we didn’t wanna do any songs from the first album because that felt like a different era. It felt like a different band. When we first came to the states and got signed to Relativity, we were kind of lobbying them to just forget about Welcome to Bop City, and just let us go on, and record a new album because it was already a couple of years old at that point, and we just felt that we would have developed further. We had come a ways. But they refused — they really liked the first album — so we ended up remixing it and releasing it. So, when we went on tour for Second Coming, that was closer to where we had developed as a band, musically, and we did not have a full concerts-worth of songs, so we had to pad that out with some covers. We did some covers of stuff we liked, like The Ramones, Sex Pistols, and Iggy and The Stooges.

Tim and I were somewhat stable financially; Stixx and Bobby the bass player were not. They were running out of money, so we went to the record company, and asked them for money, and they said, “No.” Then they came to us and said, “Well, we’d like to record an EP of punk covers to send to DJs around the country.” And we said, “Well, sure. Here’s the budget.” We did the EP as cheaply as possible, so we could pocket the money so that Stixx and Bobby could go on living for a few more months. So, it was kind of a deal with the devil, but I’m still very proud of it. Like, I listen to it, and it’s very raw, and it’s a different facet of the band, but it’s definitely in keeping with our musical mindsets. It’s very true to Shotgun, although it sounds nothing like Shotgun. I don’t know how else to put it.

Andrew:

That’s interesting. It’s fairly common for artists not to listen to their work once it’s been recorded. Do you find yourself revisiting the Shotgun catalog frequently?

Harry:

I do. Every few years I try to listen to it, not just to maintain my chops and to keep my memory fresh, but also to see how it holds up. So, when I said that the first album sometimes sounds cacophonous to me, there was a period I had a hard time listening to that album at all because it just sounded like pandemonium to me. Then comes a period where you listen to Second Coming, and the drums sound kind of artificial; there were a lot of sample drums on that. But then, as time goes on, you kind of hear what you liked about it in the first place. So, I’m very proud of all the albums, and the EP, and have no real problem listening to them today. The Violent New Breed is definitely my favorite; it never felt like it got old to me. I enjoy listening to it today.

Andrew:

It took courage and foresight for both of you and Tim to drastically alter the sound of each album. With each turn, Shotgun Messiah was ahead of the curve. What prompted you to explore different musical avenues?

Harry:

It’s not a conscious decision. You know, there have been times when we’ve tried to be contrived, tried to write what was expected of us, and it just doesn’t work. The magic is right there, right then, and two years later down the line, it’s something else; you’re inspired by something else. So, it was a natural progression — we didn’t try to change — except, of course, Violent New Breed. We lost the drummer and bass player right before starting to record the demo, and we just figured at that point, “What the hell? We’re not gonna arrange this for a traditional rock band anymore. Now we can really use the studio as an instrument. Now we can really do whatever crazy things we want to.” So, that’s what we did.

Andrew:

It is obvious that you and Tim were in an especially creative state of mind when you recorded Violent New Breed. Were you guys into any particular genre of music at the time?

Harry:

We have always been musical omnivores, so it’s not like we were listening to one thing and that’s the only influence we had. We were listening to anything from what was top-40 at the time, to what was going on in the R&B scene, or industrial, or heavy rock, or, at that point, some grunge had started bleeding in. So, we were listening to pretty much anything and everything that came our way. Veracious music listeners.

Andrew:

Violent New Breed is a substantial contrast from the band’s previous two records. Was there a blueprint behind the making of the album?

Harry:

The blueprint, usually people try to hide these things, and I guess, I haven’t really mentioned it for a long time, but Tim called me up and said, “There’s this album you have to hear.” So, I got in the car, I drove over to his place, and he played me this European, industrial thing. He’d been into Industrial for a few years at that point. So, he played me this thing called “Peace, Love & Pitbulls;” it was a very famous Swedish singer/guitarist who’d gone down to Amsterdam and did some wild stuff. It was just this really brutal kind of Industrial-with-guitars thing, and I just thought it was amazing. Immediately, we sat down and thought, “Is there any way we could arrange our stuff in this vein, with just samples, and sounds going in, and coming out?” It’s like Bob Ezrin‘s production on steroids. So, we sat down, and we worked on trying to make that happen. And the co-producer on the album [Ulf “Cybersank” Sandquist], he worked on the Peace, Love & Pitbulls album, so Tim contacted him, and he agreed to do it without knowing that we were considered a hard rock/glam metal band kind of a thing. He wouldn’t have worked with us had he known, but I guess he just liked the cut of Tim’s jib. So, we went to Sweden, and we recorded an album with him. And that’s how it happened.

Andrew:

Since only you and Tim were involved in the recording process, how did you handle live performances?

Harry:

We had access to all the original sounds. So, we had this big, honking sampler that we brought on the road, and we hooked up to an all-electronic drum kit; all pads. So, we used the sounds from the album, and they would change for every song. So, the kick with kind of an echo comeback thing on Violent New Breed, there’s like two hits, and you just have to keep it going. We had all those sounds in the sampler, and we played along to them. It was kind of scary, because if someone pulled the plug or turned the power off between soundcheck and gig, we’d have to boot up the sampler again.

On the Second Coming Tour, we toured with T-Ride, and they had a computerized sound setup. They had KM backing vocals and sound changes in the computer. They were extremely accomplished musicians and singers, so if the computer broke down — which it frequently did — they would just continue playing and sound awesome as a three-piece. It just wouldn’t be as polished as before. But we saw that and thought to ourselves, “Okay, it’s doable. We can actually pull this stuff off.” We applied some of those lessons to Violent New Breed so that if something were to break down — which it thankfully very, very seldom did — we could still pull it off; it just wouldn’t sound as polished.

Andrew:

What gear did you use to record the album?

Harry:

I had two guitars. I had a Fender Strat and I had a Les Paul — it was a replica, it wasn’t a Gibson — but it was like a Burst replica guitar. So, it was a traditional Les Paul, traditional Strat — twenty-one fret is the word — and then I just went out and I rented a couple of amps. I tried a Mesa Boogie Dual Rectifier but I couldn’t dial in a sound that was appropriate with that one, so I ended up going with a Peavy 5150. I was familiar with that, ‘cause I’d toured with it on the Second Coming tour — so, it was a familiar amp — straight into a Palmer Speaker Simulator. And then, for some of the guitar sounds also, I used Cybersank’s Rackmount Marshall Amp. I think it’s a single-space rack amp, and we used that for some of the distorted sounds, and for distorted vocals, and God knows what else, too. So, there was a lot of distortion being used on that.

Andrew:

What was the support like from Relativity at that point?

Harry:

Support from Cliff was unwavering; the rest of the label was drifting away. With any band, you have a honeymoon period where you can do no wrong, and then the label turns on you, and you can do no right. And we were pretty deep in that hole at that point. Cliff Cultreri flew over to Sweden, and he visited the sessions and everything, and I got the impression he was still on our side, but I guess the writing was on the wall. Even though I think we delivered a kick-ass album, and God knows where it could have gone had it gotten the proper backing from the label, they ended up dropping us just a couple of months after releasing it. I think they released it in, like, November or something, and by January, we were dropped. So, it never stood a chance.

Andrew:

In retrospect, you and Tim should have been on the verge of an exponential breakthrough on the heels of Violent New Breed. Given the fact that there were contemporaries who prospered, and navigated the music shift, what was the driving force behind the disbanding of Shotgun Messiah?

Harry:

It just got really difficult and uphill, and it did not seem worth the effort anymore. And at that point, Tim started leaning toward doing a solo thing, and I started looking at other band possibilities. So, that was that. Had Relativity not released Violent New Breed, like if they would have dropped us before releasing it, then maybe we could have shopped the album to someone else, and we’d be telling a different story today. But the way it worked out is it didn’t work out.

Andrew:

If Shotgun Messiah had been afforded the opportunity to make an album that followed Violent New Breed, what would it have sounded like?

Harry:

It’s very hard to say, because if you would have asked us after the first album what the second one would sound like, we would have been wrong. And the same thing, if you would have asked us during Second Coming what the third album would sound like, we would not have envisioned Violent New Breed. So, who the hell knows? But it’s a guarantee that it would have been Tim and I, so probably a lot more machines, a lot more like Violent New Breed. That felt exciting to us, and I’m sure we would have continued down that path.

Andrew:

Aside from subsequent musical endeavors, Coma and Das Cabal, were there ever any auditions or offers to join other bands over the years?

Harry:

No, no. That was not a good time to be a guitar hero. I guess I could have tried going down the more fusiony, solo artist, guitar-wankery thing, but that was never my avenue. So, I wasn’t comfortable doing that and did not do it.

Andrew:

Following the dissolution of Shotgun Messiah, you joined the band Coma. While that venture ultimately petered out, Das Cabal was an interesting vehicle because it also involved Rhino Bucket’s Georg Dolivo. What was the genesis of that band?

Harry:

Georg is just such a super fun guy. Like, if you ever get the chance to hang out with him, take the chance; he’s funny, he’s smart, he’s quick. You’ll have a good time. So, we started hanging out and we started doing some musical stuff. Neither one of us had one penny to rub together, so we couldn’t really start a band, at least we couldn’t have paid any other members — and we certainly didn’t wanna cut them in on the action — so we were just recording demos on my very limited digital system at home, and sending them around here, there, and everywhere. A couple of songs ended up in a film, and that was about it.

Andrew:

That band seemingly had the necessary intangibles to gain traction, so why was it that Das Cabal never took off as it should have?

Harry:

We didn’t really take it as seriously as we should have, I don’t think. At least, I know I didn’t; it was kind of like a side thing. I was having great fun doing this with Georg, but it just never seemed like a serious effort to get a band going. It was more, “Throw it against the wall and see if something sticks.”

Andrew:

Interestingly enough, you also played some guitar and banjo for Tom Waites, appearing on his Real Gone album. How was that relationship forged?

Harry:

It was one of those things where my wife was Tom’s publicist. So, we’d been hanging out socially, and he wanted me to play some stuff on his album. So, I drove up to where the studio was at with a couple of guitars, and a banjo in the trunk, and played on whatever was needed. It’s an interesting experience, because it’s pretty much all live. I mean, you’re sitting there, you get the music explained to you, and then you kind of all sit there all in the same room, and you’re playing this stuff. Either the take was good, or it wasn’t.

Andrew:

I don’t believe we’ve heard from you on this topic, but given the age of nostalgia, do you envision there being a Shotgun Messiah reunion at any point?

Harry:

If it is, it’s gonna be Tim and I. And if it is, then it will probably involve a new album. I don’t see us just going out, playing the greatest hits, and drinking beer. It’s not gonna be that kind of a tour. If we do something, there will probably be a new album involved. Then we go out and we gig, and we see if there’s any interest in that.

Andrew:

Were you ever close?

Harry:

Yeah. I think we came in on the bus just before COVID. COVID was on the next bus behind us. So, that killed whatever chances there were of us assembling a band, starting rehearsals, going on tour. But that was definitely being discussed, and it’s just kind of on hold now. I don’t know how Tim feels about it, I know he’s kept busy since, but I’m still holding out hope that if COVID goes away soon enough — it would be fun just to go out, and at least offer the opportunity to all the people who never got to see us back then, or who saw us thirty years ago, and really, really wanna see some more. The YouTube comments and the stuff online never really went away, amazingly. There are still people talking about Shotgun, and wanting to hear me play, and all this. So, yeah, it would be fun to give them the opportunity and see what that will do.

Andrew:

As an aside to Shotgun Messiah, have you considered releasing an instrumental album?

Harry:

No. That’s actually part two of, you asked about “The Explorer” earlier, and I told you about the origins of it. So, it was strictly written for Guitar Player Magazine, and it worked, I got in — I was in the “New Talent” column — and that’s what got us a record deal in Sweden to begin with. They’d heard the songs and were not impressed, then I ended up in an American magazine, and they gave us a deal. And I tried to talk the record company out of putting “The Explorer” on Welcome to Bop City because it didn’t feel like a Shotgun song, and they refused. They said, “This is what got you in the American magazine, it has to be on the album.” And then I had the same discussion with Relativity, “Are you sure this should be on the album? We’re kind of doing the glam metal thing here, are you sure there should be an instrumental on there?” And they said, “Absolutely.” So, it’s no thanks to me that you’ve heard “The Explorer.” [Laughs].

Andrew:

Thank you for being so gracious with your time, Harry. From YouTube, to message boards across the internet, your legacy lives on after all these years. Is there anything you’d like to say in response to the continuous outpour of adoration?

Harry:

Thank you, humbly. That’s really all I have to say about that. I’m amazed and touched that anyone still knows my name because I haven’t really put in the work for it in the last couple of decades. You’ve heard my stuff, but you’ve heard it in commercials, where you had no idea that it was me. It’s very touching that stuff we did back then, in the late 80s-early 90s, resonated with enough people, and in such a way that it’s still being talked about. It’s very rewarding.

Interested in learning more about Harry Cody & Shotgun Messiah? Hit the link below:

Be sure to check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

Thanks Harry and Andrew for this Amazing interview.

Damn I hope Tim isn’t nailed down new shotgun would be so bad ass can’t get enough VNB it’s the alien in me