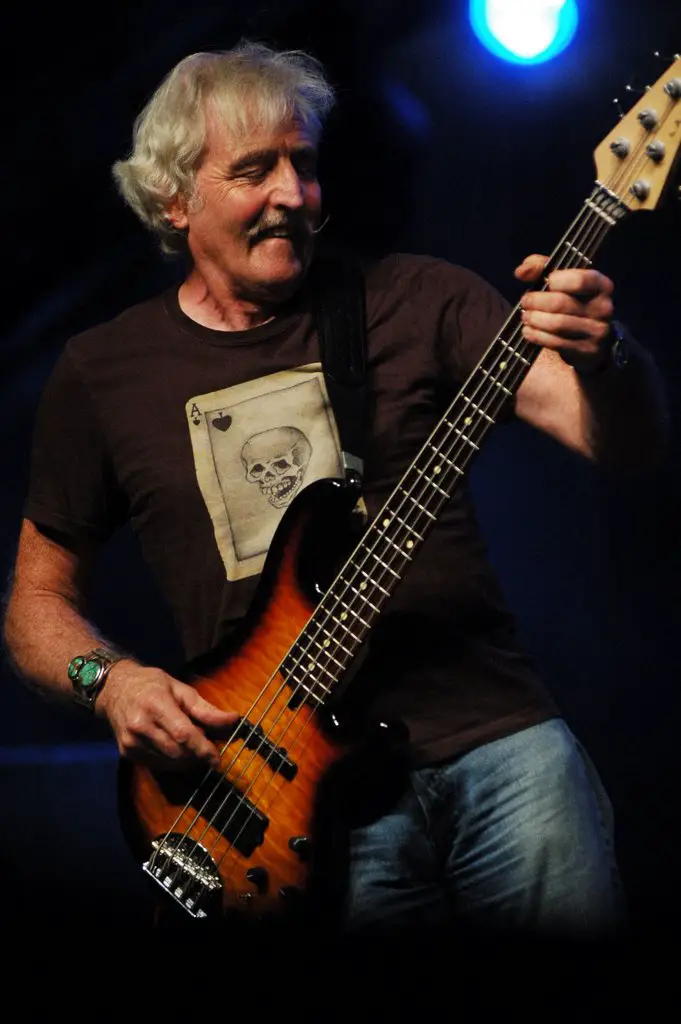

All images courtesy of Leo Lyons

One of the best parts of conducting interviews is having the opportunity to speak with some fascinating and seminal characters within the music industry. When I was given a chance to speak with Leo Lyons, a true Rock veteran, I jumped at the chance.

If you’re a fan of late 60s and early 70s Blues Rock, then you’ve come to the right place. Leo Lyons, along with Alvin Lee, was the steady, driving force behind the Rock ‘N’ Roll hurricane that was Ten Years After.

Ten Years After, a band that performed at the inaugural Woodstock Festival in 1969 and was so the first Rock band to officially perform at the Newport Jazz Festival was a group who would help to define the signature sound which was Rock music in the late 60s and early 70s.

Present-day, Leo is carrying on that storied tradition with his current group Hundred Seventy Split. In today’s chat, Leo and I touch on his musical roots, the beginnings of Ten Years After, performing at Woodstock, producing records for UFO, the formation of Hundred Seventy Split, the legacy of Alvin Lee, and a whole more.

If you would like to learn more about Leo Lyons, or Hundred Seventy Split, you can head over their respective websites and dive in. Enjoy this chat with Leo Lyons. Cheers.

Andrew:

Leo, I appreciate you taking the time today. How have you been holding up over the last year or so? What have you been up to?

Leo:

Like everyone else, I’m getting through it as best I can. We had to cancel all touring after Jan 2020. That was a shock for me. Hundred Seventy Split have nothing booked in until October 2021. It’s the longest time off from gigging ever.

I pick up my bass every now and again and play along to drum loops and records to keep up my chops and sanity, but it’s not the same.

I’ve guested on a few yet-to-be-released, remote recording projects, and I’ve also started up my own YouTube Channel. ‘Leo Lyons Musician’ where I talk about my career and answer questions.

I intend to finish my biography, which is still a work in progress. I pick it up and put it down again. I take my hat to those who’ve found the determination to complete theirs.

I’ve taken up cycling again and can recommend it as good for the body and spirit. I should be writing more. I have song ideas that need finishing,

Andrew:

Before we dive into your professional career, let’s go back a bit. What first got you hooked on music?

Leo:

Most of the men in the family were coal miners, but there was a love for music in the home. My grandfather was an accomplished singer and brass band player. His brother, Morgan Kingston, quit the mine to become a successful operatic tenor and Columbia recording artiste. I just read recently that he sang at The White House for President Woodrow Wilson.

I never knew either of them, but I remember, as a very young child, listening to my Great Uncle’s records on a windup gramophone. For some reason, amongst the record collection were 78s of Lead Belly and Jimmy Rogers (Country star). That was the first time I heard a guitar played. The sound blew me away, and I tried several times to make a cigar box guitar but with no success.

Like many of my contemporaries, I loved the Skiffle Music craze that swept the UK in the mid-1950s. In particular, I liked Lonnie Donegan. I desperately wanted a guitar but couldn’t afford to buy one, but there was a banjo in our house that once belonged to my Grandfather, and I started playing that.

Andrew:

Where did the bass come into play for you? Who were some of your early influences?

By the age of eleven, I’d managed to save enough money to buy a cheap guitar and took lessons from Frank Wooley, a local guitar teacher. In time introduced me to some fellow pupils who had a band called Paul Dennis and The Phantoms’ who rehearsed twice a week and occasionally played a few gigs, mostly relative’s weddings. There were four guitar players, and it was suggested that one of us should play the bass lines. I jumped at the chance. I didn’t have my own amp but was allowed to share an amp with one of the other players. From the outset, it was something I really enjoyed.

I eventually raised some money by selling my bicycle and guitar to buy a Hofner Senator bass guitar on Hire Purchase (deferred payment). From that moment on, I never looked back. I knew bass was the instrument I wanted to play. My guitar teacher Frank was disappointed and said that I was wasting my talent.

I listened to every record I could lay my hands on and probably developed my playing style from mishearing the original parts on the records. It was pre-YouTube, where you can find videos showing how things are done. I listened to pop, country, Blues, and Rock ‘N’ Roll, and later big band jazz like Duke Ellington. Elvis’s bass player Bill Black was an early influence, as was the bass player with Little Richard. Jazz bassists I liked were Ray Brown and Scott La Faro. I realized the other day whilst listening to random music on Spotify that guitarist Duane Eddy may also have been an influence, as was Django Reinhardt. There are so many great talents.

Jet Harris, the bassist with The Shadows, I also admired. He looked so cool playing his Fender Precision bass. I had to have one, but it was not until 1960 that I achieved my dream.

Andrew:

You’ve had a long career, with many credits, but let’s talk about recent events first. Tell us about Hundred Seventy Split. How did things get started there?

Leo:

Hundred Seventy Split started out as a side project whilst still playing with Joe Gooch in the reformed Ten Years After. I was asked by a US record label if I’d like to record a solo album with various guest artists. I wanted Joe to be one of those guests, and we started working together on some ideas. Before any other players were finalized, we had an album of material ready, so we decided to go ahead and make the record as a one-off side project whist in Ten Years After.

The band, named after a road junction in Nashville where Highway 70 and Highway 100 split, was my son Harry’s idea. We used to live on Highway 70, and we recorded the first Hundred Seventy Split record, The World Won’t Stop at Subterranean Studio’ just off Highway 70.

Since leaving Ten Years After, we’ve released a further four records and are due to record our sixth.

Andrew:

Going way back now, you became a professional musician at the age of 16. Tell us what led to you taking that step. How did you know music was going to be a career for you?

Leo:

I was about to leave school and had no plans of what to do next. I’d looked at a few job options, and none really appealed. I’d had aspirations to be a vet but could neither afford nor stomach the idea of more years in school followed by five years at University.

I’d never considered being a professional musician until I was asked by a popular local band, The Atomites if I’d like to join them when they turned professional. They’d seen me playing with my band The Phantoms in a local talent contest. The year was 1959. With nothing else planned, I said “Yes” and became The Atomites bass player. We planned to turn professional one year later (1960) and move to London to seek fame and fortune.

Andrew:

Alvin Lee and yourself formed The Jaybirds in 1962. Tell more about how the band formed. How did you and Alvin initially meet?

Leo:

Alvin joined The Atomites three weeks after I did. Our original guitarist had to leave because of parental pressure and Alvin answered an advertisement in a local newspaper. We both enjoyed the same music and hit it off immediately. Within weeks our vocalist also left due to girlfriend ultimatums and was replaced by Alvin’s friend, singer Ivan Jaye. That was when we became The Jaymen, and then not long after The Jaybirds. The line-up that turned professional and went to London in 1960 was: Ivan Jaye (vocals), Alvin Lee (guitar), Roy Cooper (Guitar/vocals), Pete Evans (Drums) Leo Lyons (bass).

Andrew:

In 1967, The Jaybirds officially became Ten Years After. Take me through that sequence of events.

Leo:

I managed the band for five or six years because nobody else wanted to do it. When we eventually persuaded Chris Wright to take on the task, we all agreed we needed to update the band name. We played one gig under the name of The Blues Yard, but Chris thought the name tied us down to one type of music; we were already playing swing Jazz, Blues, Rock ‘N’ Roll, etc. So we were tasked to go away and come up with some name ideas. Over the weekend I saw an advertisement in The Radio Times magazine for a book titled Suez Ten Years After. It was about the 1957 invasion of the Suez Canal.

I thought the name Ten Years After would be an interesting talking point and suggested it to the other band members, who all agreed with me. There’s something magical about the number Ten, both in numerology and the occult. In the tarot, it’s new beginnings. That’s the true story, although other origins of the name have been suggested over the years.

Andrew:

Your early work was published via Deram Records. They were responsible for a lot of great recordings from that era. How did you end up on Deram?

Leo:

Yes, correct. The band was building up a following in the UK on the blues circuit and we were given a prestigious weekly residency at London’s Marquee Club. Mike Vernon, Blues aficionado and staff record producer at Decca Records heard us play and signed us to Deram a new label recently formed as a subsidiary of Decca. We were offered an album deal which was unusual for the time. Most artistes were signed to make singles which if successful were put together and released on a long-player. It was a dream come true.

Andrew:

Ten Years After was one of the first performers at the Newport Jazz Festival. What was that experience like for you?

Leo:

One of my favorite and influential records was the live recording Muddy Waters at Newport (1960), and here we were on the very same festival some nine years later.

It was a feather in our caps. I believe it was the first year a Rock band appeared at the festival. It was all a very pleasant blur. Two things I remember are that the crowd was very appreciative and that I had a problem with my bass amp. Ten Years After later went on to play several shows with Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone under the banner of Newport on Tour. In fact, we played one of those shows in St. Louis the night before we played Woodstock.

Andrew:

I wanted to touch on Woodstock. With Ten Years After, you performed at the now legendary event. Looking back, what do you recall about that day? Do you have any interesting stories from the experience? It must have been pretty special being part of a concert event that included the likes of Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Santana, Janis Joplin, and more. Take us through your experience there.

Leo:

The festival was a pivotal moment in history that changed the music business forever and was definitely one of the highlights of my career. I was very fortunate to have been there.

We flew into New York from St. Louis the day of our Woodstock performance and drove from La Guardia to the Holiday Inn, Bethel. That was as close as we could get to the festival. From there, we took a helicopter to the festival site.

We already knew most of the artists on the bill and had played shows together before. I hadn’t eaten since the night before. I was thinking about going over to the catering area when Pete Townsend came striding purposely towards me. “Leo! Don’t eat any of the food or drink anything that’s not from a sealed can. Everything is spiked with acid!” That was it for the idea of something to eat.

Just before we were due to play, the storm broke. The roadies and I sheltered in the back of a U-Haul truck as the drizzle turned into a torrential downpour which shut down all the music for an hour or two. By the time Ten Years After performed, the stage surface was flooded with water from the downpour. The many electrical cables running across the stage made us think perhaps it was not the safest place to be. Steam was rising from the band and the audience. Because of the humidity, Alvin and I had tuning problems. I recall we stopped the show several times in an attempt to tune our guitars but we carried on as best as we could. At one point, Alvin broke a string, and drummer Ric Lee played a drum solo to give us time to sort things out. Despite all that the crowd reaction was fantastic and I’ll always remember it.

By the end of our show, the helicopters had stopped running, so leaving the site after our set was not easy. There was no room in local hotels, and we hit long traffic jams all the way back to NYC. By the time we got back to Manhattan, the hotel had given up my room, and roadie Andy Jaworski and I had to sleep on a table in someone’s office.

At that point, we had no idea how much the festival appearance was going to boost our career.

Andrew:

In 1975, Ten Years After broke up. What led to that decision? I know the group toured very heavily. Was burnout an issue?

Leo:

We’d done some intense touring and burnout was probably an issue but the decision to break up was really Alvin’s alone.

It was clear that he found touring a hassle, and more importantly, there was no need for him to keep on doing it. From the start, he’d insisted on being the band’s main songwriter and, as such, had reaped the largest financial rewards. He was able to retire.

With the sweet smell of success came the Svengali managers, sycophants, idiots, and hangers-on, all attempting to hustle in on the action and further their own agenda by blowing smoke up Alvin’s ass. It became too much.

We’d once shared the same dreams, but we’d grown up and grown apart. The band could never reach a compromise, so the years we’d spent working towards success were all thrown away.

Alvin once told me that he envied my need to earn money because it was a motivation for me to carry on playing music. I thought that was all very sad because it was never about the money with me.

Andrew:

Once Ten Years After had finished, you began a successful career in record production for Chrysalis Records. How did you end up working in that space?

Leo:

I was already working as a record producer before the Ten Years After break-up. Things were shaky in the band, and I needed another creative outlet. I’ve always had an interest in recording and had been recording demos at home on various set-ups since 1962. Chrysalis Records heard my demos and asked me to produce some home recordings with Frankie Miller. The work with Frankie was well received, and I was offered other production work for the label, most notably UFO. In 1975 for a time, I became Chrysalis studio manager and staff producer before becoming a freelance producer and engineer.

Andrew:

As a producer, you’ve worked with some heavy hitters, producing records for UFO, Waysted, Motörhead, and more. Looking back, what are some albums you’re most proud to have been associated with?

Leo:

I can’t be objective on my own work. I always believe I could have done things better. Once finished and turned in, I’ve never been able to listen to anything I’ve worked on until many years later.

If I had to pick one project, I’d say UFO because my association with them through three albums was very successful. Nobody at the label really expected them to do well, and it was great to help make it happen. I was also pleased with the work I did with the band Magnum. That said, I’ve enjoyed working on all the records I’ve been involved with, including those with my own bands Kick and lately Hundred Seventy Split.

Andrew:

In 2003, you returned to Ten Years After. Take me through the reformation.

Leo:

I was living in Nashville at the time, working as a staff songwriter for music publishers Hayes Music. It was a hot and humid Tennessee July and too much for me. An Italian promoter Stefano Luciano asked Ric, Chick, and me if we’d work together backing an American Blues singer Carvin Jones for some Italian gigs. A paid playing holiday in Italy was just what I needed to escape the humidity of Nashville, so I agreed.

It was not long before the suggestion of reforming Ten Years After came up. Alvin still didn’t want to do it and, although I’d not considered it before, I agreed we’d try out a few players. No one seemed to fit until Joe Gooch, who was put forward by my son Tom. Joe’s a longtime friend of his. Although I’ve known Joe since he was four, we’d lost touch when I moved to Nashville. I knew he played guitar, but it wasn’t until he sent an audition tape for the Ten Years After gig that I realized how good a player he’d become. He brought something new to the table, and I believe we replaced Alvin with a guitar player who may also go on one day to be a legend. We were very fortunate to have found him.

Joe interpreted the songs in his own way and didn’t copy Alvin’s playing aside from the signature licks. It’s a fact that many of those had started out as bass riff, which Alvin doubled, so there was continuity.

The interplay between bass and guitar was still a key element, but of course, it was different playing with Joe rather than Alvin. At first, many Ten Years After fans didn’t take to the idea, but when they heard Joe play, most changed their minds.

Andrew:

In 2013, we lost the singular talent that was Alvin Lee, and both yourself and Joe Gooch left Ten Years After. Did Alvin’s death lead to your departure? On the subject of Alvin, what are your lasting memories of him? What is his legacy within the canon of Rock and Blues music?

Leo:

Yes. I think Alvin’s death was a wake-up call that said, “None of us is immortal and if you want to do something, do it now.” His death was a wake-up call for me to question what I wanted to do with the rest of my musical life.

To be clear, I was happy playing in Ten Years After with Ric and Chick so long as I was also able to do side projects like Hundred Seventy Split. Sad to say, the other two original Ten Years After members did not like the idea. They felt threatened by what we were doing, and, in the end, we had no option but to leave.

Hundred Seventy Split is a continuation of my journey. I feel I’ve re-kindled the fire and enthusiasm I had for music when I first began, and it’s great to be working with Joe and Damon. I’m lucky to be playing with such high-caliber musicians.

Re Alvin: Most of all, I miss him. We worked together right from the beginning when we both set out to take on the world. He was the brother I never had. He was at times difficult to work with, and we fought and argued just like siblings often do, but we had a mutual respect. Sometimes we’d be close; at other times, we’d not talk to each other for months but, because of the life experiences we shared, we had a special bond that can never be broken. He was an exciting player and showman and part of an influential generation of British guitar heroes alongside Hendrix, Clapton, Peter Greene, and Jeff Beck. I always thought that one day Alvin and I would work together again on some project or other. Sadly that can not happen.

Andrew:

Are you into vinyl? Cassettes? CDs? Or are you all digital now? What are a few of your favorite albums, and why?

Leo:

We’ve released all but one of the Hundred Seventy Split recordings on vinyl.

It’s unfortunate that many young people have never had the chance to compare the various media to hear the sound differences. I don’t like the current trend for heavy compression and one-dimensional wallpaper mixes, but it’s horses for courses.

I prefer vinyl because the sound and spatial perspective are much better. The music has a front-to-back dimension as well as left-to-right. I want to enjoy what each and every player is contributing to the whole. That said, I listen to a lot of music online, Spotify, etc., and can still enjoy the song and performance.

I don’t really have a favorite recording. It changes day to day depending on my mood. One thing is for sure whilst listening to new music, I always revisit the past and discover something I missed previously. There’s so much great music on offer.

Andrew:

What other passions do you have? How do those passions inform your music, if at all?

Leo:

Any experience adds to my musical palette. As far as bass playing goes there’s always something to learn but it helps to step back from your main passion and get a different perspective on things.

I was a staff songwriter in Nashville for a number of years. I read a lot which I think is important for us all to do and especially if you’re a songwriter.

I’m always starting up a new hobby. I like to spend time outdoors in the countryside. As mentioned earlier, I’m currently into leisure cycling. Years ago, I used to have horses. Two wheels are a substitute.

I’m also interested in the paranormal, alternative medicine, and The Martial Arts, although these days in a more sedentary mode.

Andrew:

Last one. We seem to be nearing a light at the end of the tunnel in terms of COVID-19 restrictions. That said, what’s next on your docket? What are you looking forward to most in the pos-COVID world?

Leo:

I’m very much looking forward to communicating face to face with people again. There are so many adventures I want to embark on.

Music is my life. It’s who I am, and I can’t think of anything else I’d rather do. I plan to travel with my wife Sally for pleasure and also play more gigs. I’ll continue touring for as long as people want to see/hear me play. My wife thinks I’ll die on stage. Maybe so, but I hope not too soon.

Hundred Seventy Split has to get back in the recording studio. We had time booked for March 2020, which was canceled because of the pandemic.

Interested in learning more about Leo Lyons? Check out the link below:

Dig this interview? Check out the full archives of Vinyl Writer Interviews, by Andrew Daly, here: www.vinylwritermusic.com/interview

Leo Lyons is both a musician and human being of the highest caliber. I enjoyed the interview…

Hi Paul! I can certainly say that I agree. Having the chance to interview Leo was both an honor and a privilege. Thanks so much for reading. Cheers.