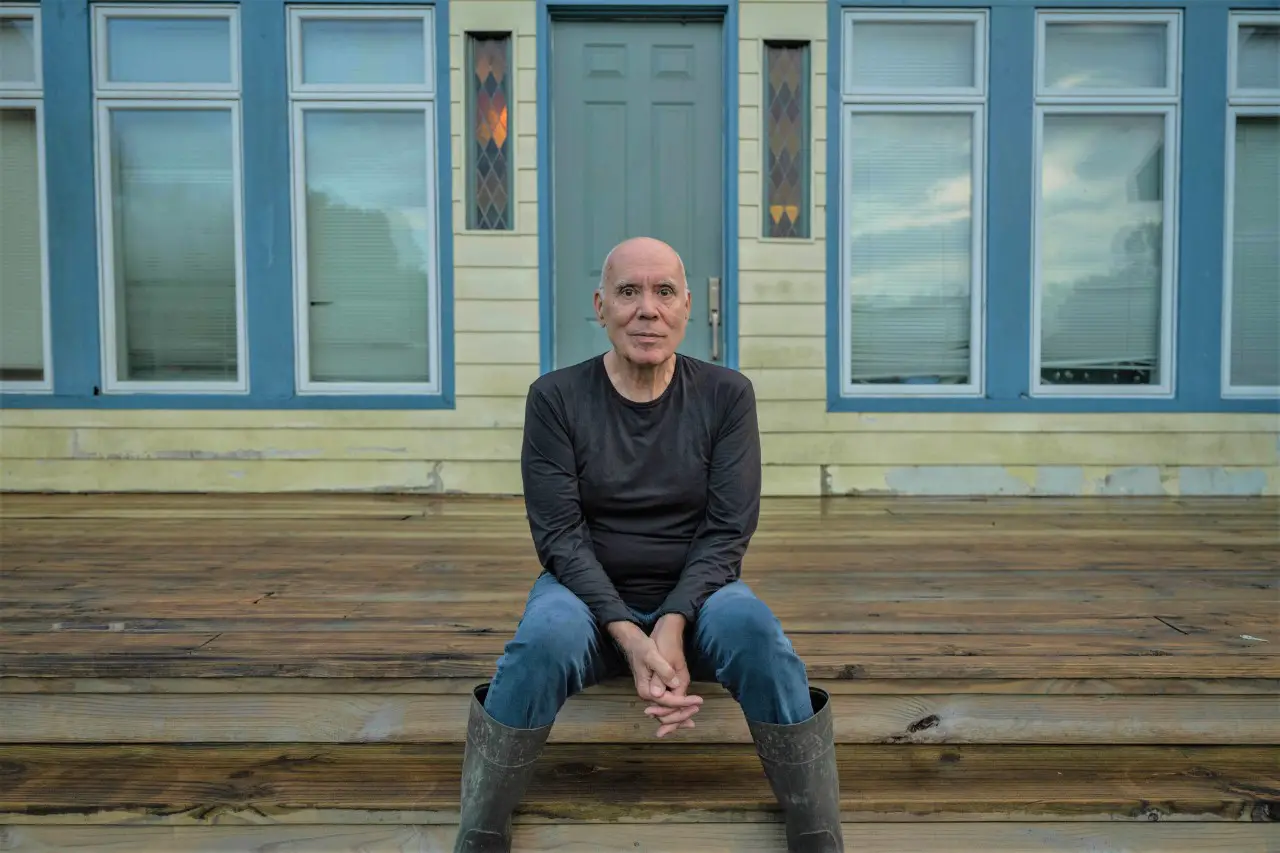

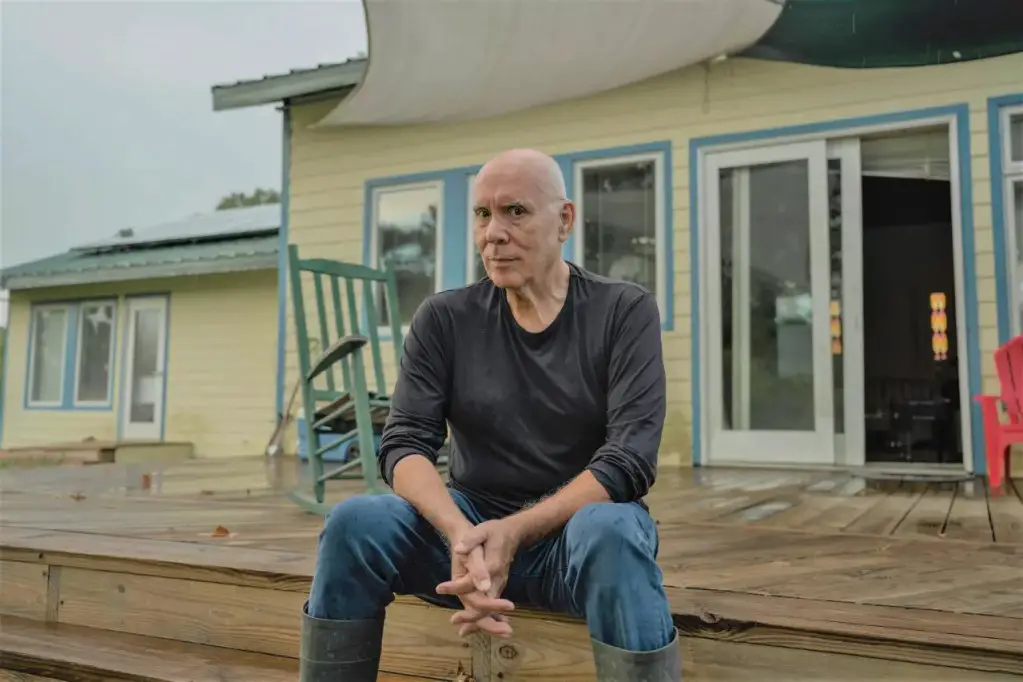

All images courtesy of Howlin’ Wuelf Media/Image credit: Olivia Perillo

By Andrew Daly

[email protected]

I recently logged time with industry veteran, musician, producer, and engineer extraordinaire, Mark Bingham. Among other things, we touched on his origins in music, his move to NY, shifting his focus to New Orleans, his love of working with artists and creating music, and his longevity in music.

If you want to learn more about Mark Bingham, the link to his Facebook is here. Once you’ve checked that out, dig into this interview with Mark. Cheers.

What are your earliest memories of music in your life?

Victory at Sea by Richard Rogers blasting through the house on Sundays, Stan Kenton, June Christie, then discovering the radio at age 7, Fats Domino, Little Richard, and rock ‘n’ roll.

What are some of the albums which first shaped your musical outlook?

Johnny Mathis’s Greatest Hits is where I found a love of standards/ great American songbook. When the Beatles hit, that opened up the world of brit rock and the R& B and blues that was the source material for the Brit invasion. Also, doo-wop and everything that was on the radio. I loved the four seasons, and I don’t mean Vivaldi. My defining musical moment was being in the back seat of a VW bug in 1968, driving across the country while playing the same song and riff for 3000 miles. My fingers hurt after that.

Walk me through your early experience signing a publishing a contract with Elektra Records.

One of my high school friends had four reel-to-reel tape decks in his basement because his dad worked for RCA. We started making recordings using a primitive overdub method, recording then playing back on one machine and recording onto the next. This got noisy and was lo-fi but allowed for some texture. We learned about loops- actual tape looping around mic stands to make beats and repeating sounds. I was layering on top of my songs.

In the mid-60s, the band battle was a common event. I lived in a wealthy area, but I’m not a Nepo Baby and not from money, but maybe I’m an Access Baby because the judges of the band battles were well-known music and media people. One of the judges took my demos to the art director of Elektra/Nonesuch. They liked it and signed me.

What can you tell me about the formation of the Screaming Gypsy Bandits?

Bandits existed in the fall of 1969, formed in the ashes of Mrs. Seaman’s Sound Band, which featured Michael Brecker and Bruce Anderson. I showed up in town, met people, and when Bob Lucas took off for NYC to join Randy and Michael Brecker in Dreams, I became one of the band/singing and playing guitar. From there, the band morphed and mutated through several phases.

What is one takeaway from that experience that you still carry with you to this day?

What I carry with me is how popular the band was until I got involved. What was originally a 1969 version of a jam band became more aggressive, and the hippies hated it. I was going to make a solo record that ended up as a Bandits record – In The Eye. I also carry with me the oddity that In The Eye, which has had no more than 2000 vinyl records sold in 50 years, is still considered some kind of important record in Indiana. I will play the album live in June.

How did moving to NYC affect you most musically leading up to the formation of the Social Climbers?

So many times, I have decided to quit music and producing only to remember it’s what I like to do despite the treachery of dealing with other humans. By 1975, I was not happy in Bloomington and made multiple terrible decisions, especially doing “performance pieces.” I moved to NYC to stop being an old hippie in a college town where everybody knew your business. Jean Shaw had graduated from IU music school and was moving to NYC.

We got a cheap loft where you could play anytime, day or not. I started doing two bass pieces. Our first show was witnessed by Dick Connette, who wanted to play with us. That started the trio. I don’t think we intended to push boundaries; we were just trying to make decent work. Being in NY was great for hearing live music, especially jazz, and the downtown composer world. NYC was a great place to be in the ’70s and early ’80s.

All images courtesy of Howlin’ Wuelf Media/Image credit: Olivia Perillo

What led you to pivot and move to New Orleans in the early ’80s? How did the Boiler Room get started?

Despite the low rents of that era and all the glory of the art and music scenes, NYC was difficult. Once the initial buzz wore off, the grind became all-encompassing. Jobs were falling through, and the band seemed to be over, so it was time to recharge. Sublet the apartment and went to New Orleans for four months which turned into 40 years. It took nine years of being in New Orleans before I was able to get a functional studio.

By 1992, I could see that getting producer gigs for labels was a crap shoot and not a lasting thing, more flavor of the moment, then discard and find new younger people. So, I opted to have a studio where I could record people and not have to deal with managers and label geeks or wait three months to get paid by Warn Your Brothers. I managed to get a good space, an okay console, and a 2″ analog machine, and there it was. Thanks to Michael Minzer and Ken Devine, angels who helped get me the gear to keep me working.

What led you to shift your focus to production? How did your career as a musician inspire your approach?

At Elektra in 1968, I was trained to be a producer. From the ground up. I was a singer-songwriter/producer. Not an engineer. I never had a full focus on producing. To make a living, I could use my skills as a player, singer, writer, arranger, producer, and, eventually, an engineer. I couldn’t make a living (or remain interested) doing just one of those roles but doing all of them allowed me to keep making music. I am not sure I have had a career as a musician. Maybe, kinda sorta, but nothing linear or ongoing. I hardly played any gigs from 1983- 2017. A few, but mostly I was in the studio, where you have to be a musician first to do what I do.

Of all the artists you’ve produced, which sessions were the most meaningful, and why?

James ‘Blood’ Ulmer comes to mind. I loved the band, and working with Vernon Reid was a dream come true. But I didn’t produce that record. It’s all a blur, and I often forget what was produced, recorded, and arranged. As per actual productions? I have to go look at the discography! The Mem Shannon LP A Cab Driver’s Blues was the most meaningful. Helping a blues-singing cab driver make a combo art piece, and blues record was the best fun ever.

Which sessions did you find to be the most challenging and why?

The most challenging session was in august of 1987 in a Burbank studio, working with Hal Willner on the Stay Awake record. The day involved; one arranger already drunk at 11 am and passed out by noon, finding another conductor for a session an hour away, one artist who faked being sick cause the pressure was on, a 50-piece band full of mean-spirited Los Angeles session players, an artist who punched out his wife, followed by a next day intervention and rehab (I do believe I saw the man take his last drink), drug dealers in limos and another singer on his 2nd 5th of Remy before he sang a word. And the label head was there, not liking any of the music we had prepared.

All images courtesy of Howlin’ Wuelf Media

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about your work arranging the horns R.E.M. How did you come to know the band?

I hardly knew the band (and still don’t) and ended up working with them because the manager liked what I did. My approach was to stay out of the way. [Laughs].

What can you tell me about working with Marianne Faithful in 2011?

I had met her a few times via Hal Willner. At one point, she came to New Orleans to play a show. She was sick, and I got a call to help her. I spent all day doing errands, getting her a doctor I knew to come to her hotel, and trying to convince her to do the show even with her throat hurting. After an eight-hour service day, I was told I had three passes on the guest list for that night’s gig. I brought two people to the show and wasn’t on the guest list. This experience also sums up what it was like to spend three weeks making a record. I was the help.

Pushing forward to the present day, there’s an expansive project afoot that will see 22 albums covered from your 50-year career. What are your musings?

Very few people on earth care if any of us live or die. Nor should they. But that hasn’t stopped me from having fun and making lotsa work.

What guiding principle has defined your career to this point? To what do you owe your longevity?

I like to do music and don’t feel I deserve any wealth, fame, or reward. Just doing it is the win. And there’s no zero-sum game despite the 2023 music biz obsession with money. And the flip side where at any given moment, there are 10K “artists” releasing music that no one will hear. I am used to not having an audience. I am used to people discovering my old music years after I made it. I feel lucky to do it and still be doing it. But I’m not sure it’s been much of a career, more like a poorly paid hobby. I have made a million dollars in the music biz over 55 years. Do the math.

All images courtesy of Howlin’ Wuelf Media/Image credit: Olivia Perillo

– Andrew Daly (@ajdwriter88) is the Editor-in-Chief of www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at [email protected]