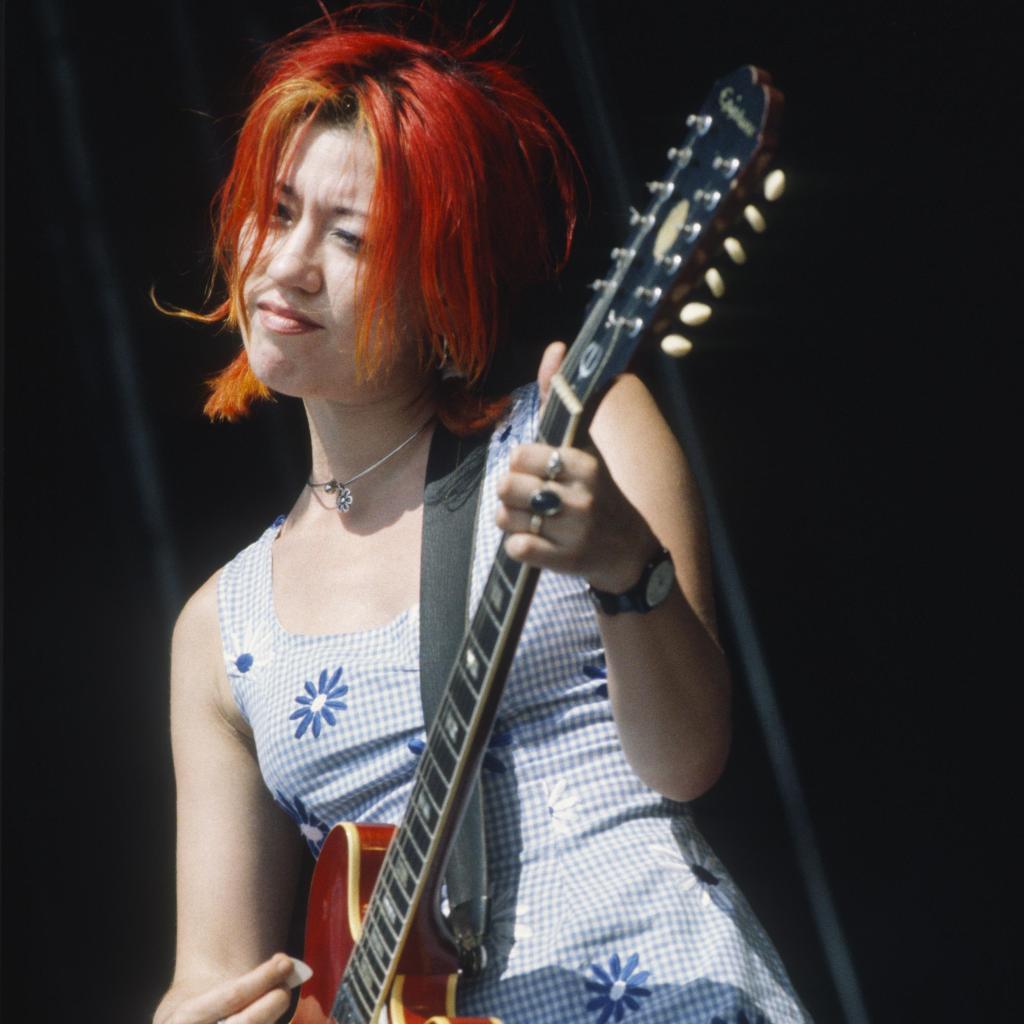

All images of Dusty Miller PR/Getty Images

By Andrew Daly

[email protected]

To curious onlookers and would-be admirers, Miki Berenyi has always been oh-so-much-more than just a girl with a guitar.

Subjected to an isolating and traumatic childhood, Berenyi turned to the arts to bandage her emotional wounds and foster a makeshift sense of community. Through film, TV, and books, Berenyi found herself a blooming adolescent, but it wasn’t until her teens that a voracious love for music sent her on a collision course.

The arrival of music in Berenyi’s life coincided arrival of Emma Anderson, a fellow guitar-toting teen who, like Brenyi, yearned for something more. The duo’s bond ultimately manifested as Lush, a blissful mix of dreamy, feedback-drenched guitars, airy, catchy melodies, and one the first bands to wave the shoegaze flag.

Though initially an unwilling vocalist, Berenyi was thrust into the spotlight as the voice of an enchanting dreamscape. With a Cherry Red Epiphone Riviera slung over her slender frame and dyed crimson hair cascading across her eyes, the songstress’s sweet voice, emotive lyricism, and carefree six-string approach helped reshape a shifting U.K. music scene.

With Berenyi out front, brash, bold, and as charming as ever, Lush seemed a band poised for decades-long stardom. But in 1996, tragedy struck in the form of drummer Chris Acland’s suicide, halting the band and effectively silencing the songstress.

Berenyi entered a period of deep reflection in the wake of Acland’s death, leading to the once defiant spitfire leaving music in her rearview mirror. But that changed when the shoegaze revival found Berenyi’s old bandmates calling her home once more in 2015.

A reformed Lush, once again fronted by a reenergized Berenyi, recorded its first new music in 20 years with Blind Spot (2016), a throwback four-song EP. And while Lush hadn’t lost its signature flair in the studio, old demons would haunt the band on the road, casting doubt over future reunions.

This time, though, Miki Berenyi didn’t walk away from music. Instead, she formed Piroshka, and when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Berenyi used the time wisely, penning her memoir, the stirring Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me from Success.

Berenyi has always been a polarizing figure, but her lionized status and madcap impact on her era are forever set in stone. Fingers Crossed is a vivid continuation of what Berenyi does best; call it a perfect companion piece to her distinctive songwriting style. And though it undoubtedly will ruffle feathers, followers of the London native’s roller-coaster career would see it as nothing short of beholden to the fire-eating vocalists legacy.

While promoting Fingers Crossed, Berenyi beamed in via Zoom, recounting the people, places, and events that shaped her musical life and her galvanizing identity as a reluctant icon.

Andrew:

Starting with your book, Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me from Success, what made now the right time to put out a memoir finally?

Miki:

Oh, I was just asked. [Laughs]. There was no plan. I got approached to write it. And it was probably quite a convenient time because I had just lost my job, and the lockdown was looming, so not a great time to look for another job. So yeah, I hadn’t planned it at all. It just seemed like an opportune thing.

Andrew:

Can you shed some light on the significance of the book’s title?

Miki:

Well, I’ll be honest; I’m not great with titles. So, the book’s title was the product of months of emails going back and forth with me trying to come up with stuff. And I think that title came quite late and was just something I just rattled off because I was getting a bit desperate by them. So, I was probably just being sarcastic, but everyone seemed to like it. And there’s a double meaning: success isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, and the music remained the best part of it. The rest of it turned out to be not particularly great for me. And the other meaning is that, like many musicians, there are other things I could have done that would have made me more successful. But I guess it depends on how you term success, but there are certainly things I could have done that made me more financially stable than music.

Andrew:

What were some of the challenges of writing the book instead of a song?

Miki:

I think with songs; lyrics especially would come from things that were very much in my mind at that moment. So, it wasn’t really a research thing; I could just be reading a particular book or being in a particular environment, which would be an inspiration. Or I could be having a certain conversation that would inspire me to mine that a bit more and come up with a lyric. Whereas, when writing a book, I had to really think about things chronologically, go back to diaries, look through photos and old tour itineraries, and immerse myself back into the past. I tried not to rely on the anecdotes and memories that had stayed with me but to think about the cause and effect of how one thing would lead to another. And that’s the most challenging part; getting the order of events right, sorting out what caused things, and where my head was at that time.

But when I write lyrics, obviously, lyrics are much more poetic and oblique, and in my case, they tend to have to rhyme as well. [Laughs]. So, you’re leaving a lot more open to interpretation and more to be guessed at. Whereas with the memoir, I needed to be quite specific – which I wanted to be – and as a result, I think it’s not necessarily an easy read. And I get that people might think, “God, why did she put all that stuff in there?” Some of it is hard to digest, like conflicts within the band and stuff that people might think I’m not necessarily covering Lush from a perspective of glory. But I think I was keen to get across the roller coaster of how I felt through all those years, which was a journey. And while it wasn’t always great, it wasn’t all terrible either. A lot of things happened at many different times in my life; I think that because I like fiction novels more than I like non-fiction, I probably tend to think in a more novelistic way. I like that there is a narrative that unfolds and a journey that you go on.

Andrew:

You mentioned that this book might not necessarily be an easy read. Why do you feel that way?

Miki:

Well, there’s a difficult childhood, there’s abuse, there’s neglect, there’s bullying, there’s promiscuity and difficult relationships, and there’s a friendship that is hard work. So, there are all those things, but there’s also a lot of humor, a lot of adventure, and a lot of great people who are flawed. I write a lot about my parents, and I’m not intending in any way for people to read that book and go, “Oh, God, poor Miki. Weren’t they terrible parents?” I’m not wanting that because they weren’t; they were just flawed, possibly in slightly more extreme ways than most people are used to. [Laughs]. But still, I’m not someone who wants to overstate that difficulty. It’s tough because you never want people that you know, or even yourself, to be judged, but at the same time, you want to be understood. And so, if you just give one burnished, happy side of a story, those people aren’t understood, and that situation isn’t understood. You have to go into the complexities of it all for people to get and hopefully relate to what you’re writing about.

Andrew:

Can you provide a snapshot of how your upbringing affected your aspiring creative mind?

Miki:

I was an only child, and my parents were split up. So, there was quite a lot of back and forth, which means quite a lot of being on your own. When you’ve got a more settled life and a routine, that makes all the difference for a child. As a child, I moved schools five times, so even trying to make friends was difficult in terms of maintaining long friendships. And I’d say being a bit lonely was integral to being creative because I was constantly looking for distractions to make me feel less lonely. I suppose that if you’re occupied, you don’t notice the negative things that are going on around you as much.

So, books, art, TV, and films were all things that I was very open to, but I think music was something that I always enjoyed, but it was also another part of this vast landscape of other cultural distractions. Whereas I think as I became a teenager, music was something that offered quite an immersive and overwhelming integration. And not just listening to music, but even being a teenager and having crushes on bands, and then going to gigs, and then there’s a whole scene of people. And then Emma [Anderson] and I wrote a fanzine called Alphabet Soup, which led to a different kind of community. So, I think it was me wanting to be subsumed in something all the time, and that led to me not having much of a private life, which I truly wanted. But still, I was quite willing to give all that up just to be involved in something that made me feel like I had a community, friends, and, yeah, distraction, I suppose.

Andrew:

What first drew you to the guitar?

Miki:

To be honest, I first played bass. But that was just because I joined a band called The Bugs, which needed a bass player, so I played the bass for them for a bit. But I think I probably played the guitar because I didn’t want to sing; I never intended to be a singer. And I thought, “Well, I need to play an instrument,” and I can’t play the drums – God knows I’ve tried – but I don’t have the coordination. So, that doesn’t leave a whole lot. And plus, I was going out with Johnny Rowland, the guitarist in a band called The Vibes, and then he was in Terminal Cheesecake too. So anyway, Johnny’s an incredible guitarist and a very patient teacher, so again, it was probably just an opportunity that I didn’t want to waste. But I wasn’t someone who watched guitarists avidly throughout my childhood and teenage years and thought, “That’s what I want to be.” It was just a way in for me, do you know what I mean?

Andrew:

Can you recount your first interactions with Emma Anderson?

Miki:

Well, Emma and I met when we were about 14. And while it became difficult later, it didn’t necessarily start that way. So, I was at school, and she came to that school, and then there was a group of about five of us girls who hung out together and got into music. And we were probably not that different from loads of other teenage girls, really. There is always a certain type of dynamic within these sorts of group friendships; when you’re a teenager, that can be very close at times, but it can also be quite problematic. There are all sorts of petty jealousies, and people grow up at different rates, and that all factors in, but I don’t think it was anything out of the ordinary.

But I think that when we both got into music later, that is probably where the fundamental differences came to be. We were both at separate colleges, but we continued to remain friends, and probably the strongest thing about that friendship was us both wanting to start a band together. And I think we both realized that we needed to do it together to make it a reality. I mean, I never had any desire to be a solo artist, and I don’t think that Emma did either. Honestly, a big reason for that might have been that we didn’t feel we were individually talented enough to do that ourselves. And if there’s one thing about bands, you kind of have each other’s backs, and it’s less daunting to have someone to bounce off and drive you forward. So really, that’s what I think started it off.

Andrew:

What are your memories of Lush’s early days?

Miki:

So, I got my mates in from college, a drummer Chris [Acland], Meriel [Barham], who was the original singer, and Steve [Rippon] on bass. Thinking back on it, I don’t think we thought that far ahead. I mean, just the fact that we signed to 4AD was like, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe that’s happening,” but we weren’t ones to plan ahead, really. It all happened very quickly; it’s not like we went for three or four years and then began putting records out. It was quick; I think Meriel left the band in November of ’88, and by the following summer – less than a year later – we were recording with 4AD in ’89.

Andrew:

What sort of challenges presented themselves in the wake of Lush’s success?

Miki:

Our relationship changed because the circumstances changed, and there was now a different pressure on us. And when you’re in that position, you then have to spend an awful lot of time together, and what happens is that you suddenly become reliant on each other. Because once we’d left college, and we’d all decided we would do the band rather than pursue different jobs, we were locked in with making the band a success. And the longer it went on, the harder it became to envision a life outside of Lush, especially if it was still reasonably successful, which it was. So, what happens is things can start to grate on each other because you’re kind of stuck with each other. We were initially together for eight years; it’s a long time to spend in each other’s company. We were in each other’s company more than anyone else’s, which gets very hard. The difficult aspects of our relationship were not necessarily that surprising. I think if you ask most bands, plenty of them don’t speak to each other anymore.

Andrew:

How did the tensions between yourself and Emma manifest into the creativity that we saw?

Miki:

I think very early on; we decided that we would write separately. And to be honest, I think initially, that was partly out of our lack of virtuosity. We weren’t a band that could turn up at a rehearsal where one person might start playing something, and the rest of us could jam along. It wasn’t that we weren’t capable of that – we were – but if we did that, then you’d probably be stuck with about two chords for a whole song. [Laughs]. I think both of us liked well-constructed pop songs, and the nature of the songs made it very difficult to write them all together. I’ve done it with Piroshka, where I’ve handed over the lead guitar part or the bass part to different members, but we didn’t do that in Lush. I think I would have quite liked that, but it just didn’t happen.

Once we’d recorded with 4AD, there were a couple of collaborations where I might write the lyrics and Emma wrote the music, but most of them were songs we wrote very separately. And if there was any collaboration, it was probably via the producer, Robin Guthrie, who might have had ideas for a keyboard part or whatever. But we didn’t do that together, and I don’t know if that was a good or bad thing. If we had done it together, our relationship might have been better. Then again, maybe it would have been a lot worse; I have no idea. I have to say there’s something about being involved with music and collaborating on it that does bind you together. There’s a real joy in all working on the same song so that you’re all involved. So, yeah, I would say that Emma’s and my separation of songwriting may well have added to the competitiveness, where it became “your songs” and “my songs” kind of stuff.

Andrew:

Your book discusses the duality between your public persona and your private identity. Once you became Lush’s vocalist, were you comfortable with that level of exposure?

Miki:

I’m not going to lie; it can be fun, and it was great when we were first interviewed and reviewed. To open music papers that I’d been reading for several years and to see my picture in them or having someone come up to you at a gig and be like, “You’re Miki from Lush!” those are all fun things to have to happen; they give you a buzz. But obviously, there’s a flip side, and I think doing interviews where the music papers were more of a tabloid, where they were something like a weekly competition, that’s where it got hard for me. Those types of papers were always looking for a story or the next big thing, and they seemed to really enjoy setting you up and then knocking you down. I don’t think it was all malicious; I just think it was the nature of that kind of media; they had to constantly keep the readers interested with something new.

So, that was quite difficult for me, and I think I was probably too frank and too honest with how I talked to the press. I spoke to them as friends – several of them were friends – but I look back, and yeah, I can say that I was too honest and upfront about things with them, which hurt me. I probably wasn’t guarded enough, but then again, I don’t think any of us were. And then it’s quite difficult when you’re reading an interview where you feel that someone deliberately had set out to make you look stupid or set you up; it makes you less trusting. And sure, there are probably much thicker-skinned people who can take that, although, to be fair, I’ve seen my fair share of people who aren’t.

But with all of that, I think it just grinds you down a bit, and the result is that you end up being guarded and defensive with the wrong people. And what happens is that suddenly, you don’t know where you are, and you don’t know where the attacks will come from. And while it seems very easy to say, “Oh, well, it’s just another tabloid paper. Who cares?” But then again, it’s not that easy, do you know what I mean? But these days, people, in general, seem to have a firmer idea of that because of social media. With social media, now everybody bloody gets attacked; you can’t open your fucking mouth without someone leaping down it or combing your social media for something you might have said four years ago. It’s funny because I always thought that might happen less because everyone was open to it, but it’s the opposite; it seems to happen more. So, go figure.

Andrew:

How are the effects of the things you went through during your childhood most reflected in the music of Lush?

Miki:

I think a part of me can’t help but end up blurting stuff out. The difficulties that I went through as a child didn’t stop me from going back and ultimately looking for more punishment. I never successfully shut myself away, which I’m glad about, but I think with music, I opened up quite a lot. I think both Emma and I opened up quite a lot, particularly on Split. Emma wrote about her father’s death, and on songs like “Kiss Chase” and “Light from a Dead Star,” I wrote about a lot of that stuff and put it out there. And then it was quite hurtful when people sneered at it or dismissed it.

Andrew:

On the subject of Split, my favorite Lush track is “Hypocrite.” Can you recount its inception?

Miki:

So, with Lush, I tended to write some of the tracks I thought would be a bit livelier when we played live. Emma would write these beautiful songs, but they were often quite challenging to play and sometimes didn’t translate to playing live. And I think Lush did quite well with having a few jump up and down songs and a few in-your-face pop songs. And with myself and Emma being the main songwriters, I was always very conscious of trying to ensure that Chris, Steve, and later Phil had a few moments in the limelight. So, I often would start songs with the bassline, have the drums be very prominent, or have a section where it’s just drums or space. But with “Hypocrite,” I think I pinched that baseline. Well, I modified it, but it started with a song by Spizz Energi called “Where’s Captain Kirk?” And then, there was a song by a band called Snuff that also had a bass intro, and they were slightly similar, so I basically modified the two of them together.

Lyrically, I think it was around the time when I was in a relationship, and being in a band, it’s very difficult to hold down a relationship. It’s not often talked about with women; it’s usually blokes who go off and have affairs, sleep with groupies, or whatever the hell; the temptations of being on tour. And it’s usually more condoned in men as well, and I felt that I got a lot of shit, basically, for a couple of flings. On the one hand, I completely acknowledge that it was out of order and very hurtful to the person I was in a relationship with. But I also felt like, “I’m getting a lot of shit for this, but when I look around a room full of blokes in bands, they’re not getting any of this crap, even though they’ve got girlfriends.” So, I think that “Hypocrite” was referring as much to my own hypocrisy of being able to dish it out and not take it. But also the larger hypocrisy of people who would judge me in a sexist way, I felt. They don’t judge the boys in that way, but they judge the girls.

Andrew:

Do you still feel any of that fear or angst residually today?

Miki:

In a way, yes. In writing this memoir, I probably should have learned my lesson the first time rather than do it all over again. But I think creatively; this is what I am the best at. With songwriting, I’ve tried to write a political song or a nice song about nice happy things like how lovely the world is, but it just doesn’t work for me. I tend to mine my personal experiences, and that might be that I’m just trying to exercise demons. Maybe I need to put them out there creatively in order to think them through. With me, it’s either I do it that way or I don’t do it at all. So, I think, yeah, I do feel a bit vulnerable with this memoir.

So yes, it hurts when people accuse you of lying or slam you for the things that you’ve said in the past. But I guess you have to put up with that when you put something like this out there. You can’t have everyone agreeing with you, and people aren’t necessarily going to like what you say all the time anyway. But I don’t know; at the same time, it’s not like I think I’m some sort of freedom fighter or some speaker of truths. I’m not “Miki the Brave” I’m just telling my stuff. I’m also speaking from my experience, like I always did in my lyrics. I suppose I’m just sometimes not prepared for how angry and upset that can make people, which is probably the story of my life.

Andrew:

Would you say music has had a healing effect on you in your life and career?

Miki:

I think music is healing. But again, people have completely different reasons for why that might be. So, I believe there is something about knowing someone who can put how you feel into words through some sort of emotional expression, whether with books or music. And I think that is probably how I relate to most art or creativity. Because it’s a connection, isn’t it? I would say that playing music, playing live, and getting a response from an audience is immense connectivity. It doesn’t matter who is in that audience; you might disagree with them on personal issues, politically, or how they live their life, whatever the hell it is, but there’s that moment where you’re all together in a room. It’s just people together, enjoying the music, and it feels like we can all commune on that level, and that’s quite joyous.

Andrew:

I once read a quote from you: “I was never a proper guitar player – only in the context of Lush.” If that’s accurate, what makes you feel that way?

Miki:

It probably is accurate. I felt that way because I didn’t think of myself as a “guitarist” in the same way that I don’t think of myself as a “writer.” I’m just someone who played guitar, and I’m just someone who has written a book. I never wanted to learn how to play like Jimi Hendrix or mine the whole landscape of possibilities before I came up with how I would play guitar. I just played the guitar to match the songs we’d written, but I wasn’t interested in developing it any further. If I thought of a song, there were ways that the songwriting would stretch my guitar playing, but it wasn’t the other way around. You could argue that I’m just plain lazy, as well. [Laughs]. You might say that I would have been better off had I done my homework, but it just didn’t interest me. The way I saw it was if you’re going to become like some sort of virtuoso, you’ve really got to love that stuff, and you’ve got to want to do it. Honestly, I didn’t want to do it, I just wanted to be in a band, play songs and write music, and it all came as a package. So, the guitar playing only went as far as the rest of it needed me to take it, and I never bothered or wanted to go further. For what I wanted to do, I didn’t need to.

Andrew:

The effect of Chris Acland’s death cannot be understated. Did you feel emotionally prepared to navigate that at the time?

Miki:

I’m always a little weary of talking about it in the context of Lush. I’m very aware that when I talk about Chris’s death, I’m often slightly centering things on myself because it is so much about the effect it had on me. It’s hard for me to objectively talk about where he might have mentally been or how he might have been feeling because, to this day, I still don’t know. I still don’t understand why that happened to him. For me, on a personal level, it was very difficult to manage because I’d never lost someone who I really loved before. It was all new to me because I’d never had to deal with death; I hadn’t really thought that much about death. And so, it was like being hit by a bus, and I literally had no way of knowing how to navigate it.

So, I was very reactive, and it wasn’t a time when therapy was that much of a thing – certainly not in this country – or counseling even. Back then, you were expected to deal with that stuff in any way you could, so I tried to do that in the only ways I knew how. I tried to get back into music or go to gigs and things, but it was just too painful. So, I just moved away from all that, which was quite good; it was good to discover a different world and have a regular job because I wouldn’t have had children without that. All of that led to a different life and a new community, which I think was ultimately a lot more stable and healthier for me than being in a band, even with as much as I’d enjoyed it.

So, I got away from music for a long time, and I think it took until the reunion of Lush to fully realize how much I missed playing music. I had just accepted that music was over for me once Chris died; I just thought, “Well, I just can’t go back to that. It’s gone.” So, the reunion did exercise that way of thinking for me. And I think it allowed me to separate Chris and his death and made them separate things that weren’t completely tied up with everything about music. But to this day, it’s difficult not to be selfish about someone very close to you dying because you’re the one who’s left behind, missing them.

Once I could do that, I realized how completely irreplaceable a close friend or anyone who dies that you really care about is. Yes, you’ve got other friends, and of course, there are partners, parents, family, and lots of other people to comfort you, but I’ll never meet another Chris. He was a huge part of my life, so I carry all of the memories I have with him on my own, which makes them kind of lacking. There’s a real sadness to that because as much as I can celebrate who he was – I could write a book about how lovely he was – ultimately, I cannot get over the fact that he should be here. I can’t get over that or the fact that it’s very sad that he isn’t.

Andrew:

What made the Lush reunion possible?

Miki:

I think what made it possible is that Phil [King] had carried on being in a band, so he had stayed in the music business. And Emma, I think Emma was working as a booking agent, so she also maintained a connection to the music industry. She had been working with Creation Records before Lush, so I think she always had more ties and was open to any role in music. Whether it was being in a band or in that industry, that’s always been her life since we were teenagers, whereas my thing was just the band. Their connections meant that they were more in touch with what was happening in the shoegaze revival, where bands like Slowdive and Ride were reforming and touring. Whereas I thought that shoegaze and the idea of Lush were dead and buried.

But I was wrong, and they let me know that, in fact, that wasn’t the case and that the possibility was there for us. And then I just had to think about whether I really wanted to go back to that because of Chris. But also just the worry that we would tarnish the legacy or that we wouldn’t be as good. I hadn’t played in bands in a long time; it took a lot of rehearsing and getting back in the saddle. But once it happened, it was great; again, it’s not something I could have ever done on my own. So, I’m grateful to Emma and Phil that they pushed for that because there’s absolutely no way that I would have done it on my own.

Andrew:

Why didn’t the reunion last?

Miki:

Well, again, in the end, various sorts of different personality clashes and difficulties came to the forefront. In some ways, you sort of think, “Oh, well, you’re 20 years older, everyone’s grown up a bit, surely the same problems aren’t going to surface,” but funnily, they do. The only difference is that you’re much more resilient this time, and you can come back from it when and if that happens, which it did. But when you’re younger, you’ve got all your eggs in one basket, making it a lot harder to where you feel like it has to work. I think the reunion was never going to be a long-term thing, I have children, and I’ve got a life outside of that, so when things started to go wrong, you just think, “Well, really, I don’t need to deal with this stuff.”

I mean, not just me, but the others as well; we all were thinking, “God, I’m too old for this crap.” But that doesn’t take away from how brilliant it was; again, you’ve got to take the good and the bad together. In the end, the personality clashes were hard to manage, and it was just very stressful. It probably would have been easier if we weren’t the kind of band that could sell quite a lot of tickets, go to America, and make a bit of money, then maybe we could have managed it better. But we weren’t big enough to be traveling in separate coaches, and basically, avoid each other if there were personality problems. So, yeah, it all fell apart again; what can I say?

Andrew:

Would you say Lush is over or is there potential for another reunion?

Miki:

I would argue that I’m someone who would never say never. But I would also argue that after writing this book, I don’t think the others would want to reunite. I think I might have burned my bridges with this, again, not intentionally, but I think that’s it for Lush. You have to understand the difficulty of one person writing a book and writing about their experience where they mine a lot of difficult stuff and put it out there from their perspective. I didn’t gloss over it; I went into a lot of detail, which could be very difficult for the other people in the book. I understand that they will have their own perspective where they feel that they disagree with how I frame things. Or they might not agree with what I’ve said, and I get that too.

I didn’t go out of my way to try and make anyone look bad, but I have a certain way of talking that is pretty frank, and I get that my way of talking can be hurtful to someone. Look, there are people I’ve written about in the book, who will read this, and who are just going to shrug their shoulders and be like, “Well, yeah, I question that. I wouldn’t agree with how you put that,” but I don’t really care. When it comes down to it, an autobiography will always be written from the perspective of the person who wrote it. I can’t sit here and say I’m a journalist; I can’t write a purely objective report with multiple voices of what happened; it is going to be my story. So, I think that, yeah, the other members who were in Lush aren’t very pleased, so I would argue that any future Lush plans would be pretty unlikely.

Andrew:

What sort of emotional toll did writing this book have on you?

Miki:

I have to say, quite a lot of it was good therapy. There’s nothing like being forced to go through some of your most difficult moments and look at them from several different perspectives. And the passage of time does truly help make sense of a lot of that stuff in ways that it didn’t back when I was going through it. We all have our baggage, some of which gets overlooked too often. I certainly could look back at something like the abuse I went through as a child and think, “Well, I’m fine. That happened, but I’m fine.” But really, you don’t just get over these things, but by going back into it, you start to see the long-term effects of what going through that kind of damage can cause you.

So, when you lay out the entire narrative of your life, you can draw certain threads through it, which is basically reconstruction, isn’t it? Then again, it could be that in 20 years, I will look back at it again and draw different threads. But you have to try and make sense of it; you have to do that so that the person reading it can have something to grab onto as a narrative. In a lot of ways, I suppose that’s probably what therapy is, isn’t it? It’s looking at the cause and effect and thinking, “Was that repeated or learned behavior?” Writing the book has helped me identify things and work them out, but I’ve never really had proper therapy, so I don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about. I’m just guessing.

Andrew:

When you look back, do you have any regrets or anything you would change?

Miki:

I mean, yeah, probably. It’s difficult because there are certain things that I might not do, but then again, those things that seemed like a negative at the time might have led to things that were quite positive for me. I don’t know, I guess it’s a bit like those sci-fi things where you want to go back in time, and it’s like, “Well, maybe if we kill Hitler, then 6 million Jews don’t get slaughtered.” But then you think, “If we fuck with history, what happens?” I don’t know if it works that way, like, if we were to change anything, would things be different, or might they be the same but happen at a different time? I know that regret is funny and maybe dangerous because you never know what comes from that, either. But look, if there is one thing that I wish I could go back and change, it’s if someone could tell me which bit I needed to change so that Chris doesn’t kill himself, then I’d fucking change that bit. I just don’t know which bit that is. That’s the problem.

– Andrew Daly (@vwmusicrocks) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at [email protected]

Thanks for this incredible interview! Now I HAVE to read this book.