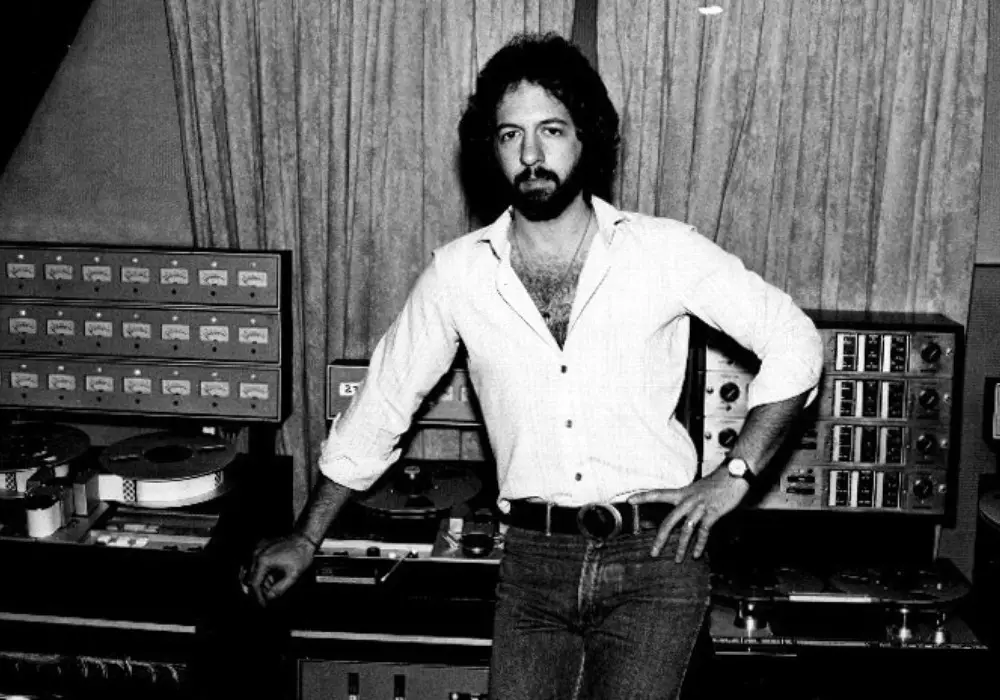

Header image courtesy of Tape-Op

By Andrew DiCecco

[email protected]

Over two decades have passed since Tom Werman last steered the helm of a recording session, but the renowned record producer – whose fingerprints are found on twenty-three gold and platinum records – has firmly cemented his legacy in music history for his deep-rooted contributions to rock music.

With a celestial resume that includes, but is certainly not limited to, Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, Mötley Crüe, Dokken, Twisted Sister, and Poison, Werman has indubitably presided over his share of watershed albums during his years as an active producer and was gracious enough to spend some time with me revisiting his past.

Part one of my two-part conversation with Werman explores, among other things, his initial entry into the music industry, his successful signings and the notable ones that slipped away, and his work with Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, and Mötley Crüe.

Andrew:

Tom, I can’t thank you enough for taking the time. I’d like to begin by discussing your formative years, so what was your initial introduction to music, and what kindled your passion at a young age?

Tom:

I don’t know. You know, it’s just who I am. I started to absorb every note of stuff that I liked when I was nine. My mother kept a baby book and noted that I was very into rhythm as a baby. I would sit on the floor and bang my hand on the floor, keeping time to music. Then when I got to be nine, I started listening to the radio all the time. And coincidentally, that was 1954, when Elvis started recording. Elvis changed my life, basically. I got bold and I got strong; when I listened to Elvis, I was invincible. He was so different than everybody else, like Pat Boone and the stuff my parents listened to. Anyway, 1954, to me, was the genesis. That was the beginning of rock ‘n’ roll. I think it went to about 1990 – or maybe ’95 – for me, and I think it was an era that was defined by those two years. I found that music moved me emotionally and I needed it. I had to have it. When music was playing, it was a colorful world; when there was no music, it was black and white.

I realized after a while, when I got to be twelve or thirteen, that my ability to absorb and retain music – and play it in my head and hear all the individual instruments – and just easily memorize and replay in my head every instrument’s part in many pop songs, I realized that other people couldn’t do this. I started to realize that music was much more important to me than it was to most of my friends, except for a few. And that was it. I taught myself how to play the guitar; when I got to college, I had a really good band. I played every weekend, usually both nights, and never had so much fun. We were very good; we got a summer job at one of three discos in New York, and I actually turned down an audition for Brian Epstein.

Andrew:

That actually ties into my next question. What was that audition for and how did the opportunity present itself?

Tom:

We were playing a private party and we took a break, and one guy came up to us and said, “You boys are really good. I’m Nat Weiss and I am Brian Epstein’s attorney in New York, and I think Brian would like to hear you.” I said, “Well, look, let’s just say we had a hit record. We’d have to tour, right?” And he said, “That’s what they usually do.” And I said, “Sorry, we can’t do it because we’d be drafted immediately if we dropped out of school.” I was such a trained seal by my parents. I mean, if I had dropped out of college to be a musician, they would have just killed themselves. I was upper-middle class, destined for corporate leadership. That’s just the way it was. So, I said, “No. We can’t do it.” It took a few years for me to realize it was a big mistake. Then again, if I’d become a rock ‘n’ roll musician I might have OD’d and died. I just don’t know. I wasn’t very disciplined back then, except for obeying my parents.

Andrew:

Your entry into the music industry was rather unconventional, as you originally started in advertising. If you wouldn’t mind, walk me through how you earned your earliest job in the industry, which I believe was with Epic Records as an A&R guy.

Tom:

I was getting an MBA to stay out of the war, basically – and my parents wanted me to get an MBA because they wanted me to be a CEO – and I had three interviews; I had Procter and Gamble, Grey Advertising, and Gillette, and they all offered me jobs. I turned down Procter and Gamble – people thought I was nuts because that was the big, plum job for MBAs – and I turned down CBS Records because I thought they were too small, and they weren’t offering the highest salary. And the fact that salary was more important than the actual nature of the job was just remarkable to me later on. I thought, “What the hell was I thinking that for $1,000 a year – which was significant in 1969 – that I would choose a different career?” It was just nuts. So, I started working at Grey Advertising on Procter and Gamble products – Jif peanut butter and Gain detergent – and I was absolutely miserable. So, after a year, I wrote to Clive Davis and I said, “Listen, here’s my situation; I’m a musician, I love rock ‘n’ roll, I have a job, I have an MBA, and I think I’d rather work for you.”

So, I started interviewing over there and eventually I got to Clive, and Clive hired me. I wanted a job at Columbia, but he said, “There are no open positions at Columbia, but the Director of A&R at Epic, our smaller label, needs an assistant. So, why don’t you go there?” I was disappointed, but I was delighted to be in the record business. So, I started at Epic Records, and like three months after I got there, I was learning the ropes. Basically, they gave me an American Express card, and my job description was to go find the next big thing. Pretty good job.

Andrew:

Which you did, as you were responsible for identifying acts that ultimately achieved meteoric heights. How did bands like Cheap Trick and Boston first come onto your radar?

Tom:

Well, Cheap Trick, Jack Douglas called me and said, “I saw this band and I think they’re very good, and I think you should sign them.” I knew who Jack was and I had great respect for him. I had signed Ted Nugent before Cheap Trick, and Ted was managed by David Krebs, who also managed Aerosmith. So, I had known Jack kind of through that connection. I respected him, and I jumped on a plane and went right out to see Cheap Trick. I saw them in a shopping mall – in a club in a mall – and I liked them very much and went back to New York and said to my boss, “You gotta come and see this band,” because that’s what we had to do then. I didn’t have the authority to sign bands on my own at that time. So, we both went back out – and Krebs came out with us – and with the strength of the manager and the fact that we could get a good booking agent, the whole picture looked positive. And that’s how I found Cheap Trick.

Boston was a freak occurrence. I was sitting in my office one day and Lennie Petze, a colleague, came in with this guy Paul Ahern, who was their manager, and he said, “Tom, I’d like to get your opinion on something.” Our boss was out of town, we went into his office and put a demo in the machine, a cassette, and the first song was “More Than a Feeling.” It was very close to the album version. And we played it and we started the second song, and either somewhere in the second or the third song – and I can’t remember which ones they were, but they were superb – I stop the tape and I said to the two of them, “Is this Candid Camera?” Because I could not believe this was happening naturally to us. A&R people chase bands, look for the bands, search for the bands, and get into signing battles. This band walked into our office at four o’clock, this manager, and asked us to sign them, saying that everybody else they had seen that day in New York had passed. It was truly unreal. I just couldn’t believe it. So, I said to Paul, “If this band can come anywhere near what this sounds like live, you’ve got a great deal. I guarantee you.” So, Lennie and I went to see them at The Wherehouse, which was Aerosmith’s rehearsal place in suburban Boston, on Thanksgiving vacation. They were good enough, so we signed them. And they sold 16 million albums on their very first release.

Andrew:

Perhaps equally impressive are the bands you lobbied for and tried to sign but were ultimately denied, like Rush. What’s the story there?

Tom:

I think, Ray Danniels, who eventually, I think, managed Aerosmith at one point. He’s from Canada, and I think he just sent me a cassette, which I heard. I don’t think anybody referred me to them. So, I flew up to Toronto to see them. He met me, we had dinner, and we drove out to this little high school in Mississauga, it’s a suburb of Toronto. They played, and they were marvelous; they weren’t totally alternative, but they were really good. They played effortlessly, and each one of them was superb on his own instrument. And they were only a three-piece. So, I said, “Wow, I wanna do this,” and then I went back and I wrote my usual memo. I think somebody like my boss must have heard the music, and we went ahead with the deal, but Business Affairs called and said, “Too expensive. Can’t do it.” It was too expensive because the band wanted $75,000 for two albums, firm. I mean, really, chump change, and of course, CBS Business Affairs had its guidelines. So, pass. And then Cliff Burnstein signed them at Mercury right after we passed.

Andrew:

How about Lynyrd Skynyrd?

Tom:

Well, Phil and Alan [Walden] had founded Capricorn Records. After the Allman’s, they got ahold of this band, and Alan Walden came to my office in New York. He was very soft-spoken, very well-dressed, mild-mannered, and talking about his band in Alabama. Then he left me a cassette with “Freebird” on it, and “Give Me Three Steps,” and I don’t know what else. He was very nice, and I liked him and lot, and I liked the music a lot. So, I flew down to Atlanta, drove to Macon in Georgia, and there was a roadhouse there, kind of a bar/club, outside of town. I saw them, and they had two drummers – one on either side of the stage – and they rocked the house. I mean, it was serious. Very serious. I loved it. I flew back, I said, “Don [Ellis], you gotta come and see this band. We gotta sign this band.” Don and I flew down to Nashville and saw the band play at the Exit Inn. You know, they played a great set, with “Freebird,” and we left the club walking back into the parking lot, and Don said, “Good band. No songs.” So, that was that.

It was the same story with KISS. He didn’t like the band. I can understand why he didn’t like KISS because he wasn’t a hard rock guy. He wasn’t even a rock guy; he was a pop and yacht rock kind of guy. I loved him; he was great, and he was a good executive, and he was a great guy and was smart, but he just wasn’t into rock ‘n’ roll; the kind of rock ‘n’ roll that people were buying a lot of right then and making a ton of money. So, he passed on KISS because he didn’t get it.

There was also, later on in my life, when I was at Elektra Records briefly – I was the head of A&R at Electra Records – and I went to New York because we had meetings at the Elektra office in New York and I was in L.A. and the second-in-command at Elektra, Bruce Lundvall, who had been the president of CBS Records a long time before that, he asked me to come downtown with him to see this African American girl who played a private audition for us with a nice pickup band. She was absurd. I mean, she was so good, that when she was finished, I just looked at Bruce and laughed. There was nothing to say. We talked with her, we went back up to the Elektra offices and told the president of Elektra, “You must go see this girl right now. She’s incredible.” And he went to see her, and a couple of weeks later, he told Bruce, “Why should I sign someone who sounds like Chaka Khan when I just signed Chaka Khan?” Which he had done at Warner Bros. before he came to Elektra. And it was Whitney [Houston]. So, that one got away, too.

Andrew:

Your first production credit was on Ted Nugent’s self-titled debut in 1975. What led to you signing Ted and how did you transition from A&R to producer?

Tom:

The transition wasn’t anything I planned. First, I have to explain that Ted and I didn’t talk politics back then. He wasn’t a political animal. And I love Ted, but I abhor his politics, and I’m sure he knows that. Anyway, we are still in touch once in a while. And I think, as a person, without politics, he’s wonderful.

I signed Ted because somebody told me he was available. His manager, the guy who owned his production deal, came into my office and said, “Guess what? Ted Nugent and the Amboy Dukes broke up and Ted Nugent is available.” I knew nothing of Ted Nugent. The A&R department had to go to Chicago for LaBelle – we had signed LaBelle – and they were playing, so we all went to see them and it was kind of their debut for the label. Ted’s manager said, “I’ll put together a show.” So, he booked a little show at Illinois Institute of Technology, and I went into their auditorium – there were probably two or three hundred people there for Ted – and he was phenomenal. I said, “This is it,” and I went backstage and I talked to him, and we hit it off. Again, I went back to New York and I told my boss, “You gotta see this,” and we went back out to Lansing, Michigan, to an ice arena, where he was opening for Aerosmith. Again, Krebs was there, and my boss said, “Fine. This is great.”

The thing was, this was five years after I started at Epic. And you know that I tried to sign three bands that became huge that my first boss did not want. So, when he left – the guy who passed on that – the guy who took over, Steve Popovich, when he got there, he said, “Werman, what have you been doing here for the past five years?” I said, “Well, I tried to sign blah blah blah…” And he said, “Well, that’s interesting. Is there anybody you’re interested in now?” I said, “Yeah. I’d like to sign Ted Nugent.” So, he had just started, and he and I went out to that Lansing, Michigan ice arena. And he said, “Okay. So, we’ll sign Ted Nugent.” Meanwhile, this guy Lew Futterman – who was a nice fellow and a good manager but not a rocker – he went into the CBS Studios in New York, right down the street from the offices, and they started making the record and I said, “You know, this guy is not a rock ‘n’ roll head. He doesn’t get Ted.” So, I started kind of horning in; I would sit in the studio and kind of timidly suggest things to him. And I started going more and more frequently and making more suggestions. Then I remixed the record myself with an engineer because I didn’t like his mix, and he gave me a co-production credit. And the album went nuts and sold a million in a few months, and all of the sudden, they considered me a producer. Then my first solo job was Cheap Tricks In Color.

Andrew:

You mention Cheap Tricks In Color, which is an album that has a definitively more refined sound compared to the self-titled debut. You were able to evoke their melodies and tap into the band’s inherent musicianship, so how did you polish that edge, so to speak?

Tom:

Well, a lot of my artists thought I was too pop. And I am a pop guy – I’m not a metal guy – so the way I approached producing was to get the most commercial elements of the song and feature them so that I can make hit singles because that’s the way to album sales. I think one of the reasons I did that is because it was a proper thing to do if you worked for a record label because they wanted to sell records. The band’s artistic integrity was not the most important thing; commercial success was the most important thing for me at that time. So, you know, I kind of lent a pop element to the harder rock because if I had made much harder albums, they wouldn’t have gotten on AM radio, and AM radio was the key to a hit album. And that’s the deal. Every time I made an album, I insisted that a designated member of the band approve the final mixes. So, every album I finished was approved by the band. Then, twenty years later, I sucked. They loved you then – high-fives, back slaps, “You’re beautiful, babe” – and then twenty years later, “Oh, he didn’t pay attention to us. And it was much too light, and it didn’t rock hard enough.” They revise history, a lot of them. That’s one thing that distinguished Ted from many of the others; he always said, “Werman was responsible for preserving my sound and helping me make records the way I wanted them.”

Andrew:

That seems to be a common theme, unfortunately.

Tom:

The ugliest part of the entertainment business in Hollywood is that they’ll love you, they’ll tell you how great you are, and they’ll include you in everything. But when you get to the point where you can’t do something for them – you can’t help them with something – then you basically don’t exist anymore.

Andrew:

Which is truly a shame, because, in many ways, you’ve helped transform and launch careers.

Tom:

Yeah. Well, with Mötley Crüe, I made three records with them that were very successful. Then when they decided to go with Bob Rock, which after three albums, it’s not unusual to switch producers – and Bob did a fabulous job with Dr. Feelgood – they had their record release party, and they didn’t invite me. And I was like living five miles away. It’s typical. Really not cool.

Andrew:

Looking at Ted Nugent and Cheap Trick from a guitar perspective, what are some ways in which Ted’s approach and style differed from Rick Nielsen’s?

Tom:

Well, Ted was very planned and very organized. My role in his first couple of albums was really quality control rather than composition and creativity because he would basically tell everybody exactly what to play; he had all the parts worked out in his head before we entered the studio. Rick was completely the opposite. He would finish writing songs in the studio, and he would establish his basic guitar lick, but then he would ad-lib. He was much more of a shredder. Ted had really good parts and fills. Their whole approach to composition was different. Rick kind of didn’t enjoy playing the same thing twice, and Ted would stick to the program.

Andrew:

Dream Police went in a commercial direction, but in what measurable way would you say Cheap Trick evolved from the In Color sessions?

Tom:

Well, Rick had more to say about that album. He did a little arranging; I think we put strings on a couple of songs. I don’t know what it was – technology – [but] In Color was lightweight. I think Heaven Tonight and Dream Police were probably the two best albums I ever produced in terms of what I contributed.

Andrew:

Why do you say that?

Tom:

Well, because they’re great. [Laughs]. I love those albums. I think the songs are great and I think the production is really interesting. It’s interesting. I did all the percussion; I arranged most of the keyboards. What happens is, the band finishes, and then I bring in a keyboard player and say, “Let’s sweeten these songs. I’d like a Hammond B3 here. And I’d like you to play this.” I sing it to them because I can’t read or write. You know, I made more of a contribution on those albums, and I think they were well-mixed, well-produced, well-written, well-played. In Color, it was early, and I was just getting used to the band. I think by the time we got to Dream Police, I knew what they were capable of and what they did really well, and I drew on that and asked them to do that. That’s all.

Andrew:

You handled the production for Mötley Crüe’s Shout at the Devil, the first of your three-album run with the band when there was an especially tumultuous vibe within the band. What led you to the opportunity?

Tom:

Well, there was always a tumultuous vibe, but they were in much worse shape when we did Theatre of Pain. We had been put together by a guy who worked for me when I was head of A&R at Elektra very briefly; I lasted four months there because I couldn’t deal with the new president of the label. When I left, they wanted me to do a production deal with them and do three albums; I did Mötley Crüe, Dokken, and I can’t remember the third.

We met, we had a meeting; Nikki was tough, Tommy was OK. Tommy was really the diplomat. They gave me demos, and they had a lot of songs because it was very early in their career, and I took them home, I made some changes and we rehearsed, and then we went into the studio with this very good and very divisive, untrustworthy, kind of evil engineer. I didn’t use him for that long. We made the album pretty quickly; it was tough because Nikki had a car accident and broke his shoulder, so he played his bass parts in a cast with a sling. Certain things took a long time – their sound was pretty rough, I thought. Most of their fans like the sound of that album, and I like the sound of the Girls, Girls, Girls album because Mick sounds much better. I just think they sound like a major league band.

People like the gnarly quality of Shout at the Devil, and the songs were more elementary than the later songs. I think “Wild Side” wasn’t necessarily the best song for singing, but certainly the most interesting production that I did with them. They got better and better. Nikki wasn’t that good on the bass, I thought when we started, and he grew into his instrument. Tommy was always brilliant, and so was Mick.

By the way, have you seen Pam & Tommy, the series?

Andrew:

You know, I’ve heard so much about it, Tom, but I haven’t had a chance to check it out. Is it worthwhile?

Tom:

Yeah, we’re watching it, and it’s actually pretty good, but Tommy is portrayed as a real jerk. And he’s a really nice guy, Tommy. He’s got a good sense of humor, he’s cheerful, he’s optimistic, he’s cooperative, and they made him a real dick. I just don’t understand how he can allow that. She’s very good as Pam. Anyway, I would recommend that you see it.

Andrew:

Making a note of that now. How did you manage to reign in four highly dynamic personalities long enough to record that record?

Tom:

When they got to the studio, they were reasonably involved, and they wanted to succeed. They weren’t just complete party animals. Vince was a little bit of a challenge, only because he wasn’t really involved in the concept of being in training. He would party pretty heavily all the time, and sometimes he would come in in bad shape. Instead of going home and having some tea and going to bed early, knowing that the next day he was going to have to sing a very important song, he didn’t really consider those things. So, he was tough. Mick was always pretty straight, pretty diligent, and well-prepared in terms of what he was gonna play. And he had some really great licks. His guitar licks were the basis of all their songs. Nikki and Tommy were dabbling in heroin and that was tough; it’s not good for decision-making. Tommy was always on; Nikki was on-and-off, mercurial, difficult to pin down, and sometimes in a good mood and sometimes not.

One day they came into the studio – I think we were doing Theatre of Pain – and Nikki dumped a whole shopping bag of candy bars in the control room. He just dumped them on the table. I think, later on, I said to my engineer, Duane Baron, “What’s with all those candy bars?” And he said, “Dude, they’re junkies!” I had no idea. And that’s when I learned about the association between heroin and sugar, whatever that is. Anyway, that was difficult, but I never had to – with any band – corral them and whip them and drive them and make them get together. You’re always a little bit of a psychiatrist within bands. There’s politics there, and there’s always one leader. You know, I had a really difficult time with George Lynch. And I liked George; He’s a genius guitar player. He’s incredible, he’s underrated, ane he’s not mentioned enough. But he and Don Dokken were oil and water; they did not get along. George usually hated the songs that Don wrote. He didn’t like the ballads, and Don was a crooner. Anyway, it went like that. So, that was a little difficult to control.

The most difficult thing I ever did was Rockstar. The last thing I ever did was a movie, and it came out a week before 9/11, so it disappeared. It was a good movie, I would recommend it – and it did well on video – starring Mark Wahlberg and Jennifer Aniston, and it was about the Judas Priest story. In the band, were Jason Bonham and Zakk Wylde; they were very explosive and difficult personalities. And Jeff [Pilson] was a really good, buttoned-down team player. He was mature, settled, and organized. So, I needed somebody like him. Jason, at one point, I guess I was talking with him about his behavior, and he said, “Listen, I’ve got a behavior to uphold,” talking about John Bonham. There were fireworks in that studio. So, that was the most difficult project I had to do.

Andrew:

When you recorded Shout at the Devil at Cherokee Studios, how did you approach the recording process?

Tom:

You know, every band wants to record live. When they walk into the studio, they want to record live. They don’t get it, they don’t understand. So, I let them record live and then I tell them to come in and listen and they’re horrified. So, what we do is we just build from the bottom up. They go out and play, and you keep a good drum track. And then you re-record the bass on top of the drum track until it’s what you want and you continue to stack and build a pyramid. That’s just the way we did it. There was no unusual approach. We did it instrument by instrument, even though it sounds pretty natural, I think.

Andrew:

It certainly has that gritty and raw sound to it that fans tend to gravitate to.

Tom:

Yeah. For me, a little too bottomy; but they’ll say that the second and third records were a little too toppy. That’s the way it is.

Andrew:

I would have loved to spend more time discussing Theatre of Pain, but for timing purposes, I must at least ask how the iconic power ballad “Home Sweet Home” came about.

Tom:

I did the same thing with that, kind of, because you can hear it, that I did with “Every Rose Has It’s Thorn.” You know, that didn’t come together. Tommy walked in with it, and he sat down and played it on the piano. And then I just orchestrated it. It was very easy. I don’t really remember exactly how we recorded it – what we did first, what we did second – but Tommy did play the piano right there in the studio. It was pretty amazing.

Andrew:

As we transition to Girls, Girls, Girls, I want to revisit an interesting comment you made earlier when you mentioned your affinity for the song “Wild Side,” my favorite Crüe song. What is it about that song that is significant to you?

Tom:

Oh, God. Everything. I just love that song. I love it. A mixed guitar part with the insistent rhythm underneath, and I think it was one of Vince’s better vocal performances. And the drums were just great. Tommy was just starting to experiment with samples. I don’t know – the subject matter, the lyrics – really good. I just thought it was a wonderful thing. And then we had that cityscape section at the end, where there was supposed to be a guy outside a strip club saying, “Come on in, guys. Check it out.” And then gunshots, and a scream, and the siren. We had a lot of fun doing that, along with “Girls, Girls, Girls,” where I played the Harleys in the front and the back. I was the guy on the bikes. I don’t remember, honestly, too many of the other songs on that album. I didn’t think all that much of them, but I did think that “Girls, Girls, Girls” and “Wild Side” were really good. And I still do.

Andrew:

When you first heard the song “Girls, Girls, Girls,” did you immediately know it would be a hit?

Tom:

Yep. I really did. I don’t do that frequently, I don’t claim to have a golden ear, but there were a few songs along the way, like “Surrender,” and “Cat Scratch Fever” that I knew immediately were hits. I’m not that quick to identify a hit, I have to listen a few times usually, if it’s good, in order to get it. But those, I got immediately.

I mean, I saw Ted play “Cat Scratch Fever” for the first time at a live show. And right after the show, I called my boss, Steve Popovich, and I said, “Hey, Steve. Ted has written a single,” because he never had. He didn’t have a single before that. He had heavy FM radio play on “Stranglehold,” but with “Cat Scratch Fever” you could tell; it was the guitar lick. Actually, most of the immediate hits were built around rhythm guitar licks. Really good ones.

Mick used to come up with really good guitar licks. Mick Mars was highly underrated; he wasn’t appreciated. He was a very good worker in the studio, and he was fast. We loved working together.

Andrew:

Mick’s guitar sound on Girls, Girls, Girls was much more polished compared to the two records you worked on previously. What did you do to elicit that sound from Mick?

Tom:

Well, you know, you learn. You learn about which amps to use, which guitars to use, and which mics to use on the amps. One of the main reasons he sounded so polished and so good, was his guitar tech. I think it was Rudy. By the time we got to Girls, Girls, Girls, he had a really good guitar tech who took care of his stuff, kept his guitars in shape, and just knew a lot about the whole guitar players’ world. That sound is what I think the band really complained about twenty years later, or thirty. It was too good. It was a really clear, great guitar sound, but it was probably not gnarly enough for the guitars on Shout. Shout at the Devil remains probably the fan’s favorite, whereas mine is clearly Girls, Girls, Girls.

Andrew:

Now, how does the budget for Girls, Girls, Girls compare with the funds allotted to make Shout at the Devil?

Tom:

It was bigger, but it wasn’t a terribly expensive album. I think the Poison album was the most expensive album I ever did. Maybe Twister Sister was hanging in there, too. By the time we got to Girls, Girls, Girls, [Mötley Crüe] were a good band. Tommy always knew how to play, Mick always knew how to play. They were great. Nikki improved a lot from the beginning, and Vince was Vince. [Laughs]. He didn’t get worse or better.

Andrew:

What was your approach to recording Vince’s vocals? I understand you implemented the use of a Sennheiser mic at one point.

Tom:

I did the first album, then I think somewhere in the middle of the second album, I used a Sennheiser mic. I always wanted to find a mic that didn’t make him sound like what he was. He used to sing through his nose, instead of through his throat. You know, he had kind of a nasal, thin tone. And I discovered this mic and I bought one. It was like a $2,000 microphone, and I used that from then on.

With Vince, it was not a question of what he sounded like, but pitch. We worked really hard, and as I think I probably said before, he partied a lot and he didn’t go into training for a recording session. I mean, he could have been up until four o’clock the night before and come in at noon to do vocals. So, that wasn’t good. We had to work long hours sometimes for Vince.

Andrew:

How drastic of a contrast was it tracking Vince’s vocals, compared to, say, Don Dokken?

Tom:

Well, Don was good, but the biggest gap between singers’ was Vince and Robin Zander. Robin was clearly the best vocalist I could ever hope to work with. Robin was just remarkable. He would rarely hit a bad note, and we could do – in the space of four or five hours – we could do two whole songs with him doubling his vocal and putting harmonies in the choruses. I mean, he was really incredible. In some cases with Vince, it would take two days to get a single vocal track. But he was a hard worker. Vince, he hung in there, but they had different vocal strengths.

Be sure to check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

6 thoughts on “An Interview with Record Producer Tom Werman (Part 1)”