Back in the 90s, finding new, off-the-beaten-path music wasn’t as easy as it is today. With modern tools like Spotify, YouTube, and Bandcamp, finding bands is literally a click of a mouse away. No, back in the day, you had to rely on word of mouth. My personal favorite was always the local independent record store.

Around that time, the best place in Las Vegas was Big B’s, a shop that was right on the fringe of the college campus of UNLV. True to the area demographic, the clerks were all either college kids, members of local bands, or both. The amount of knowledge of the underground and independent music scenes was quite respectable, and I was eager to learn. A few of them knew my tastes quite well and would often simply put an album in my hands, with an ominous utterance of “You need this. Trust me.”

And you know what? They were always right.

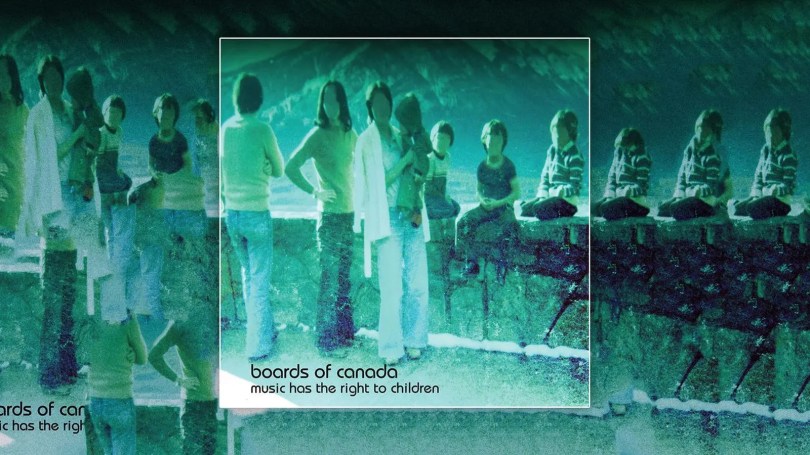

On one such occasion, a clerk with whom I was rather friendly with put a copy of Boards of Canada’s Music Has The Right To Children down on the counter when I went to check out. I didn’t even question it. It went right in my bag along with the rest of my choices. I had no idea I had just purchased an album that would alter my personal musical landscape entirely. Credited to Michael Sanderson and Marcus Eoin, it would be a few years until I really learned about the duo who created what is easily one of the most important albums in my life and musical journey.

As it turned out, they were brothers, hailing from Cullen, Moray, Scotland. They lived for a brief amount of time in Calgary, Canada, where it’s apparent that the experience left a lasting impression. Naming themselves after the National Film Board of Canada, they used many different types of recording techniques while evolving their sound, from tape loop and cut up experiments to sampling to flat out degrading samples to the point that they lost all semblance to what they started life as. This enabled their music to take on a new, otherworldly sound.

Their first few albums would only be given out to close friends and family. Twoism would be the first release available to the public, sold through their mailing list on their own label Music70. The 8 track EP was enough to catch the attention of another innovator, Sean Booth of Autechre. Marcus and Michael sent his label a demo copy of Twoism, which resulted in the release of the Hi Scores EP under Skam in 1996. This would be their proper introduction to the world.

Their first full-length release, Music Has The Right To Children, was released by Skam and the legendary Warp Records label on April 20th, 1998. I myself got my hands on it in August of that year. At the time, I already was listening to bands a bit more left of the dial, with a strong leaning to the Electronic and Industrial side of things. This album was on another level to me entirely in terms of production and sound design. Things I didn’t know you could aurally accomplish at the time. Eye-opening? Yeah, you could say that.

Kicking off with “Wildlife Analysis,” a track sounding straight out of a 1970’s PSA or ad campaign from a lost, multi-generational VHS tape. It sets the tone for the rest to come. “An Eagle In Your Mind,” with its stuttering beat constructed from samples of Michael’s girlfriend speaking, fades in. Whispered and cut-off vocal samples which you can never quite make out along with the drawn-out bell tones in the background, eventually give way to a strained “I Love You” as the song’s beat becomes regulated and bass melody hits.

“The Color of Fire” plays out like a fragmented memory of telling a family member you love them. A wonderfully used Sesame Street sample of a child gradually constructing the phrase “I Love You,” is itself a sign of the continuity used in BoC’s music, builds over soft twinkling synth tones. As the album continues on, it’s like listening to home movies intertwined with 1970’s educational videos and TV station call sign interludes. The blending is seamless in the brother’s hands, from the halcyonic “Turquoise Hexagon Sun” and “Bocuma” to the twisting, disorienting darkness of “Sixyten” and “Rue The Whirl.”

“Roygbiv,” easily considered by most as the album’s centerpiece, is undeniably bright and playful. Kicking off with a bass line that beautifully compliments the slinky beat, it’s the pitch-bent lead and the floating piano flourish that sends this song into classic territory. As the album leans into its final third, the funky “Aquarius” feels like a drive through a seedier part of town. Calls of “Yeah, that’s right” and laughter feel like taunts. At the end, and feeling almost like breaking through clouds, is “Open The Light.” Quite akin to looking through the window of a plane just as the first rays of sunlight hit at dawn. It’s a beautiful send-off. The actual spoken PSA of “One Very Important Thought” closes out the album.

Albums that could pull such strong comparisons to real-life situations were something I wasn’t used to at the time. The use of samples of children’s voices, degraded vocal fragments, and random TV snippets help accentuate the atmosphere. Evoking memories like that of a fading Polaroid or a conversation that’s just out of earshot. It’s both familiar and alien. Even after all these years, it’s still one of the most rewarding albums that I return to constantly.

This release really wound up altering my perception of music. From that point on, I craved similar outings, and I looked for other challenging genres and sounds. More or less, I wanted out of my comfort zone. To this day, I am constantly searching for the next eye-opening, mind-expanding musical experience.

I’ll always look back on these fondly half-remembered memories of a life I never led, all thanks to two enigmatic Scottish brothers. I’ll forever be thankful for that.

Interested in learning more about the music of Boards of Canada? Check out the link below:

Dig this? Check out the full archives of Left of the Dial, by Keith Kowall, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/left-of-the-dial-archives/