All images courtesy of Getty Images/Tom Beaujour/Richard Bienstock

If you’ve been searching for a book that chronicles the gradual rise of the Hard Rock and Hair Metal genre of the 1980s, including the compelling backstories of many prominent figures of the era, you’ll want to grab a copy of Nöthin’ But a Good Time and let the good times roll.

Authors Tom Beaujour and Richard Bienstock have a remarkable knack for placing readers in the moment with every page turn, resulting in a perfectly crafted masterpiece that encapsulates one of the most iconic eras in music history.

While sifting through a decade infused with notorious debauchery and the youthful exuberance of unapologetically pursuing your dreams at all cost, Beaujour and Bienstock seamlessly navigate the story in a way that makes you feel as though you’re along for the ride. Nöthin’ But a Good Time, to be released on March 16, includes over 200 interviews with artists, producers, managers, and everyone in-between, offering a myriad of perspectives and recounts.

Whether you experienced the era firsthand or are living vicariously through every twist and turn, no stone is left unturned in this comprehensive time capsule.

I recently sat down with Tom and Richard to discuss, among other things, challenges they encountered throughout the writing process, the rise and fall of shred guitarists, the drastic musical shift of the 1990s, Sunset Strip, and much more.

Andrew:

Tom, is this the first time you and Richard have collaborated on anything of this magnitude?

Tom:

On a specific book, yes. But, we worked together at Guitar World Magazine and Guitar Aficionado Magazine for a bunch of years, so we’ve collaborated on a lot of issues of a lot of magazines that have come out. Never a book, but we probably worked on 50 magazine issues together and we were co-workers for the same company for quite a while, starting in the mid-late 90s. We have a long history of knowing that we can get along and work on a project together.

Andrew:

What inspired you to chronicle this particular musical era?

Richard:

The most obvious thing is that it’s music that we both love, grew up on, and that we really have a deep knowledge and appreciation for. As Tom was saying, we’ve worked together a lot of years, so we would bring it up from time to time. It was actually Tom’s idea to do this, and then we just started talking about it together on and off over the years. I’ve said this before but I do believe it to be true — I think that we both were sort of hesitant to dive into it even though we both knew we wanted to do it; because of our passion for it and our fandom, we kind of felt like it was something that we would just get so deep into that I think we were both nervous about taking the plunge. That turned out to be true; we did get extremely deep into it, as you can see from the finished product.

Tom:

I was always completely entranced by this music, especially being a guitar player. I was 15 in 1986, so, you get that one window where the music that’s happening, is the music of your youth. It goes into your brain and gets associated with all these experiences. By the time I got to writing about music professionally in the 90s, it was the period where no one wanted to hear about this stuff. So, even when I was working at a guitar magazine — which a couple of years earlier had Reb Beach on the cover, Nuno Bettencourt on the cover, Vito Bratta on the cover — by the time I got there in the early 90s, it was like this stuff never happened. So, I didn’t get the opportunity to interview these guys, because nobody wanted to talk about Hair Metal in the 90s. It was like this whole era that I never got to talk about. It seemed like if I was ever going to write a book, it would be about this, because it’s the music that I have such passion for.

Andrew:

Richard, how long was this project in the works?

Richard:

From the time we actually started the book, proper – meaning we started putting together a sample chapter – I’m going to say it was 2017. The last few years felt like decades, so I don’t really know what time is anymore. So, I think we’ve worked on it for a solid four years, almost. It was pretty steady that whole time. It ebbs and flows. There were periods where it was moving pretty quickly and there were periods that were a little slower and we hit walls with different things, whether it was trying to reach certain people or just not knowing exactly where you’re going to take the narrative. We were probably in contact daily for a number of years working on this thing.

Tom:

I just looked at my calendar, because I remember that it was my birthday when I interviewed Jay Jay French [Twisted Sister]. That was my first official interview for the book, and that was mid-March 2017. So, it’s been four years.

Andrew:

Talk about the copious amount of research that went into chronicling an entire decade.

Tom:

One of the good things about this book, was that we both already knew a lot about it. We weren’t starting from zero, which was good. So, I didn’t have to do research to figure out that a bunch of the members of Britny Fox came from Cinderella. For every interview, we did like 200, you gotta be ready to go and kind of have to know the answers to the questions ahead of time in a weird way. You don’t want to let stuff slip and you want to be able to follow it up. The way that you get to the really good stuff, which is the surprising stuff that you’ve never heard before, is by knowing the subject well enough that you can sort of guide the interview. The subject of the interview, once they realize that you know what they’re talking about, open up. I would say, for Rich and I, we went into these interviews really prepared.

Then, as you keep going, every interview you do is research for the next one. If you talk to Jeff LaBar and he tells you a really funny story from Cinderella about something that Fred Coury from Cinderella does, then you’re doing your research for your Fred Coury interview by doing your Jeff LaBar interview. It snowballs, and by the end, you have all these new facts that you’re dealing with. When I did the Lita Ford interview, I made sure I read her autobiography; same with Sebastian Bach. If there was a book by the person, I had read it. If there were podcasts or other interviews – I didn’t want to get caught saying something dumb or not following something up because I hadn’t done my homework.

Richard:

Yeah, I would agree with that. I don’t really know if in any case I actually had to listen to any music to research for any interviews, because it’s just music we’d been listening to for our lives. If there was a book – like I remember I was flying back from somewhere and I had a Bobby Blotzer [Ratt] interview coming up – and I remember specifically spending that entire flight just reading his book from front to back. You sort of know the general arc of a band’s story, but you want to get those deeper facts that might spark a different sort of conversation and take the narrative in a different direction that could be interesting. Or, it could also lead to a dead end.

So, you would try to find out these sorts of facts that you haven’t known all along and see where they might take you. Often, they would take you into the story that would then lead you to the next person who was part of that story. All of the sudden, you’re building this multi-person narrative where they all have eyes on the same story and can tell it in a way that’s deep and rich and puts the reader right there in that moment.

Andrew:

What did you find to be the most challenging part of the process?

Tom:

One challenging thing was, that there were a couple of people who it took a long time to get for the book. I don’t think I’m talking out of school because he ended up doing it and did a great interview, but I probably have 18 months’ worth of emails trying to nail down a Sebastian Bach interview. That’s really difficult because when you are trying to tell the Skid Row story, you gotta get the Sebastian Bach interview. Rich and I would sit on the phone, like, “Oh my God, what if we don’t pull this together?” So, there were a couple of interviews that were really sort of labor-intensive to get.

Then, when you get all this material, the second hardest thing is figuring out what to leave out, because this book could have been twice as long. I’m not saying it would have been a good 1,200-page book; there would have been a lot of boring stuff, probably. But, figuring out how to weave together all of these stories, and what to put in and what to leave out, and what’s interesting and what’s not — it’s like you’re shaving down a piece of wood. I mean, we did so many passes at this book, trying to make it as compact and entertaining as possible. You’re editing it down — 50 words here, 30 words there — but in the end, all of those little nips and tucks make the whole thing flow better. Not giving up on that, when you’re dealing with 160,000 words — which is what I think we handed in — can be really overwhelming.

Richard:

I would say I agree with Tom; a lot of the challenge is getting some of these guys [for interviews]. But, I think that’s less of a challenge and more of an anxiety-producing sort of endeavor because, at the end of the day, there’s only so much you can do; they’re either going to say yes or no. If they say no, that’s it and you’re just kind of done. Sometimes you can get a work-around, but usually, that’s what happens. So, there’s kind of an endpoint with that.

The thing that I felt was the biggest challenge was, that we made such an attempt to go so deep with these stories and with the people and talk to so many ancillary people around them. Once we got down to the nitty-gritty of writing, we have just faced with so much material and so many voices and so many hundreds of thousands of words of the transcript. You know the story in your head, but it’s almost like, how do you carve it out and put it on paper in a way that is very entertaining and also really tidy? And, that it not only makes sense in that story but also when you get to the next chapter. Everything has to flow. You’re doing that for a decade of music, really. I think there probably was a point, I know at least for me, where it felt very overwhelming to think about how to carve this all out. But then, once we got into it, it just starts to flow a little bit.

Andrew:

There were over 200 interviews conducted for this book, beginning in March 2017. Take me through that extensive process.

Tom:

A lot of it was great. Everybody I spoke to was actually super cool, especially once they realized that you’re a true fan of the music and that you’re not going to ask them the same five questions that everyone else asks. I had a great time doing the interviews, especially ones like Vito Bratta — who doesn’t do interviews — or finding Matt Smith, who was the original guitar player of Poison. Some people you talk to, you aren’t expecting it, but like, Brian Forsythe from Kix is just totally hilarious. Every member of Vixen is totally hilarious.

You really have this great conversation with people, so generally, it was super pleasant. Once in a while you get an interview — like Tom Keifer from Cinderella — that I’d been trying to get for a long time and it happened while I was traveling to visit my family. I was grabbing my wife’s cell phone, and you’re just like “Oh, fuck!” ‘cause you know it’s your opportunity.

Talking to Rikki Rockett, I’m such a huge Poison fan, so it was like, “Oh my God!” There was a lot of being relatively starstruck in a way, because you’re talking to people who, when you’re 15, you were watching them on MTV. So, for me, that was totally fun. I kind of miss doing interviews for the book some days.

Richard:

I’d say the same thing. Neither of us are strangers to doing interviews; it’s what we’ve been doing for decades through the magazines that we’ve worked for. But, to do something like this, beyond the fact that it was just doing a lot of them, every interview on its own was more or less great. Every person that we talked to was actually really open and honest and happy to talk about this stuff.

There might have been a few cases where, in the process of trying to bring them on board, they were a little wary because a lot of these people haven’t been treated that well by the press in that past. But, once you got them on the phone and they saw that you were really a fan — and not a fan in the sense of being a fanboy — but you really knew the music and were treating the music with respect and reverence, they were happy to tell you all sorts of things. I think they were also pleased at how much we also knew and brought to the conversation. Then they could say, “OK, these guys are really fans of this stuff and they really know about me.” That makes them more open to talking to you about whatever you may ask them.

Andrew:

The Sunset Strip in Los Angeles was an integral component to the essence of the music scene in the 1980s. Transport me back to that moment in time.

Richard:

Well, I think that the scene on the Sunset Strip was like nothing that had come before and nothing that has happened since. You hopefully get that sense of things from reading the book, that, beyond just the sheer amount of fans that were out there at the height of this in the mid-80s, it was just so immersive; not only for the bands, but for the fans. The thing that people kept coming back to, was that it was a 24/7 party, it was Mardi Gras, all these things. But, you don’t get the sense that they’re exaggerating.

There’s a great chapter in the book where it’s all the bands talking about flyering on the Sunset Strip and everything that went into that. You really get a picture of hundreds of bands out there and just tons and tons of fans and these guys posting thousands of flyers everywhere. Every show being an event. At that time, the goal was to make every show and every day an event in and of itself. I think that’s what’s what got a lot of these bands over. You would play at the Troubadour to 200 people, but you would act like you were playing at Madison Square Garden and bring that kind of show with you. For some of them, it made it an easier transition when they did move up into that world because they had been acting like that — even when they had nothing. Now, they can just express it on that actual stage. But it was already there.

Tom:

As much as there definitely was partying, these people were young, so they had the ability to do both. That scene was so intensely competitive. In the 90s, it wasn’t cool to be like, “I want to be in the biggest band in the world and play arenas and have a No. 1 hit,” and I think for every kid who was in a band on the strip, that was their dream. They weren’t afraid of saying it; they weren’t afraid of doing what they needed to do to get there. There was a lot of hard work and a lot of hard decisions made in those bands. Sometimes, you had to get rid of your friend or do this or that to make the band the band that you wanted. It was about being fully energetic, ambitious, and unapologetically going for it. I think that’s something that was lost in later decades as far as rock music was concerned.

Andrew:

Were there any interesting stories that you weren’t previously privy to that were uncovered along the way?

Richard:

There’s a part of the book that focuses on the designers who created a lot of these looks for the different bands, and there’s actually only a few of them who worked with all different bands. One of them is a woman named Fleur Thiemeyer; she’s an Australian woman. Among the many bands she worked with — from Scorpions to Van Halen — she worked very closely with Mötley Crüe. She actually designed the Shout at the Devil costumes, which, to me, are maybe the most iconic costumes of that whole era. Those costumes themselves probably played a large role in Mötley Crüe becoming Mötley Crüe.

The thing that’s interesting about [the costumes], she tells this whole story about the guys coming to [Fleur’s] apartment in Santa Monica one day. She had actually sketched out each of their costumes, printed them up, and gave each member a copy of the piece of paper with the costume on it and a bunch of colored pencils. Each guy sat down on the floor of her apartment and basically colored in their costumes the way they wanted them to look. Mick’s is black and has some blue on it and Nikki’s was black and had some red on it, or whatever the case may be. They also put little notes on the pieces of paper saying whatever type of accents they wanted on it.

[Fleur] is telling the story, and you can just picture these four guys — who were the four badasses in Mötley Crüe — sitting on her floor coloring. To top it off, in the final copy of the book, we have the actual original sketch that Nikki colored in and it has his notes on it as well. So, to me, having that poster on my wall as an eight-year-old and then hearing the story behind how it actually came about, was a fascinating pull-back-the-curtain moment.

Tom:

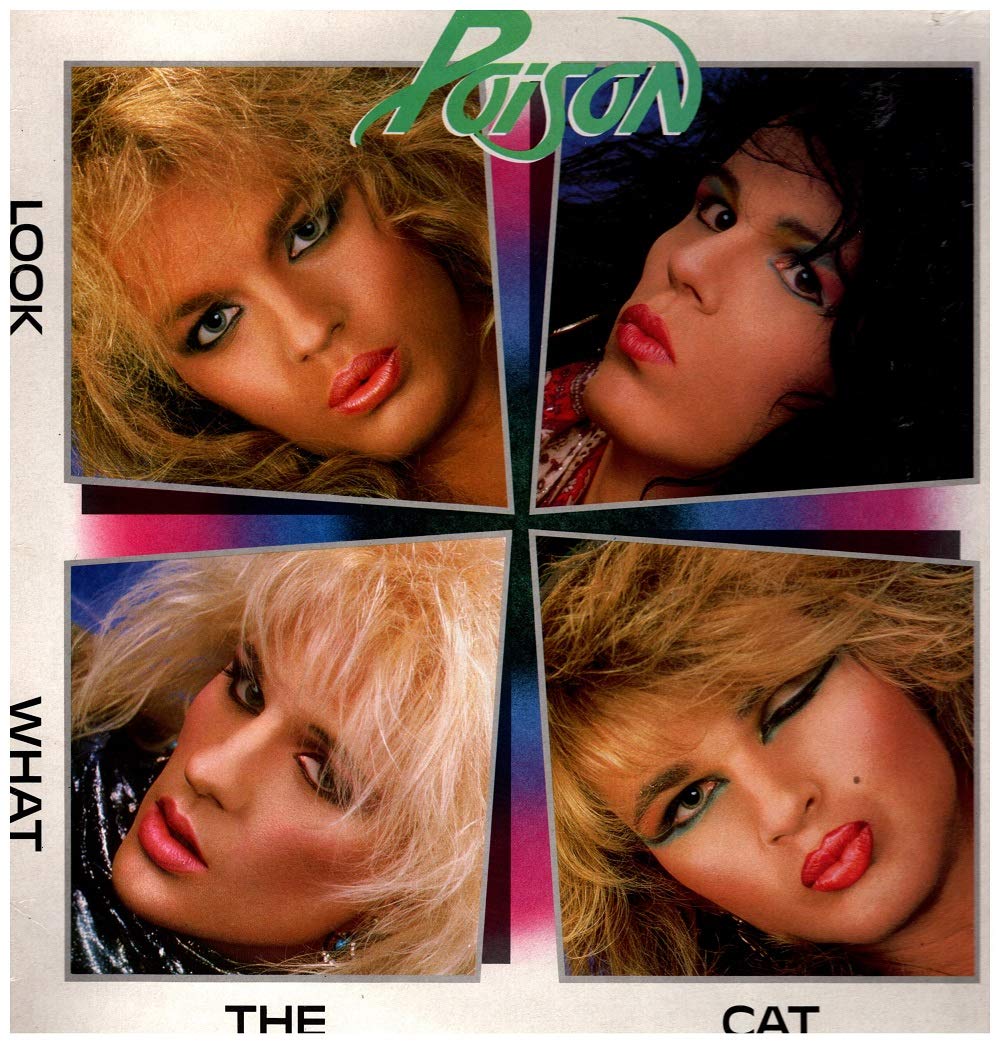

One of my favorite albums of all-time is the first Poison record. People have always talked about how much makeup the guys are wearing on the cover of that. In our book, [drummer] Rikki Rockett actually reveals that what happened was, that they weren’t wearing nearly that much makeup, but on the day of the photoshoot, C.C. DeVille still had acne back then. So, when they did the photos, they didn’t have the money, so they hired an airbrusher. The airbrusher completely blew out their faces like that. When they got the finished photos, they’re like, “Oh my God, this looks crazy!” Bret Michaels wasn’t into it, but they didn’t have a budget to re-do the photos. This album cover that’s become so iconic and controversial — and some people use it as the “Exhibit A” as to why this music was too glammy — it kind of happened by mistake.

Andrew:

Due to the plethora of wide-ranging interviews included in this book, how were the assignments divided?

Richard:

It wasn’t really planned out or specific. On the one hand, we both kind of gravitated to certain bands, and not necessarily always, “I like that band more, so I’ll take them,” but we just kind of went in certain directions. I think at the end of the day, I probably wound up doing more West Coast bands and Tom wound up doing more East Coast bands. It wasn’t strict, because, in each band’s story, there might be a case where one of us talked to some of those people, but the other person talked to more, so that person was the one that incorporated all of the material together.

All that said, there were those bands that we also did gravitate towards because we have a particular affinity for them — whether it was Tom doing White Lion or me doing Faster Pussycat.

Andrew:

Tom, Vito Bratta [White Lion] has remained largely out of the public eye for 30 years. How did you manage to get him on board with your project?

Tom:

Props to Eddie Trunk. We interviewed Eddie for the project and had known Eddie for years from my time when I was the editor at Revolver. I don’t know Eddie that well, but I was like, “Could you possibly put in an email to Vito Bratta?” I don’t know if we were lucky or if it was a good day, but [Vito] just came back and was like, “Yeah, I’ll do it.” I wish I could tell you it was more crazy than that. I think I ended up doing three hours with Vito.

We conferred back-and-forth a little bit via email and then I did like 90 minutes one day. We did a lot of early stuff; I was trying to get a better picture of the New York scene at that time. So, we spent a lot of time during the first interview talking about the early days when he was in Dreamer, seeing Twisted Sister, and L’Amour [music venue in Brooklyn, NY]. We went pretty deep with that and kind of ran out of time, but he was super gracious to do another interview.

I don’t think he’s gonna come back. He said he hadn’t played guitar in a really long time, certainly electric guitar. I don’t think he’s played [electric guitar] in like ten years. He plays some Classical guitar. I think he’s one of the people that — the 90s really blew his mind. He doesn’t blame the demise of White Lion on Grunge. In fact, he looked at his calendar and he’s like, “Look, White Lion played our last gig before Nevermind ever even came out,” which was an interesting point. I think it really hurt him deep down in his soul that suddenly the way that he played guitar was considered to be lame. There’s a quote of his in the book where he’s like, “Somebody came up to me and said ‘You know what your problem is? You played too well,'” and he was like, “Well, what am I supposed to do with that?” I think the stigma that this music had in the 90s really took the joy out of it for him. He was delightful, but I wouldn’t expect to suddenly see that he’s back and playing guitar anytime soon. I hope that with this book, he sees how appreciated he is, and it brings him some joy. It didn’t seem to me like he was itching to get out there.

I can’t underscore how delightful he was to talk to, and it’s not just because of what a good guitar player he was; he’s just funny as shit, man. He was funny, nice and really easy to interview, maybe because he doesn’t do them that much. For me, that was my white whale.

I say this as a joke, but it’s probably serious — the whole book was probably an excuse to interview Vito Bratta.

Andrew:

Richard, who was your favorite band or artist to interview?

Richard:

I really enjoyed interviewing the Faster Pussycat guys. They were just a lot of fun and have a really unique perspective on this. Their career is entertaining — especially the early days on the strip and Taime [Downe] starting at the Cathouse with Riki Rachtman — which led to a whole side excursion into the history of that club.

I interviewed Ozzy and Sharon [Osbourne] about a whole bunch of different things, which was really great. I’ve talked to Ozzy a few times in the past, and he’s always great because he’s Ozzy. But, Sharon’s perspective was really important as well, to have that management perspective.

It was funny the way Ozzy came on board. When I was doing the Sharon interview, because we were talking about very specific moments from the past that she probably doesn’t really talk about that much anymore, I could hear Ozzy in the background. He kept kind of shouting at her whenever she would answer something and kind of chiming in when it would spark something in his mind. Like, when you bring up one of his old bassists [Don Costa] who was only in the band for a minute. So, we were talking about Don Costa, and my guess is that Sharon does not talk about Don Costa very often, so he would hear her saying things and start yelling from the background, “I punched that guy in the face!” Apparently, they did get into some fight and Ozzy actually did punch him.

Eventually, once we finished the interview, I thanked [Sharon] for her time and I said to her, “I hear Ozzy in the background answering some of these questions. Can you get him on the phone for me and I’ll just ask him all this stuff one-on-one?” It was, “Oh yeah, sure,” and in a couple of days, Ozzy was on the phone and we were doing this great interview. It was really neat to have things come about like that with somebody like him, who was thrilled to talk about this stuff. Sometimes, you’re not sure if they really wanna go back and talk about the 80s again, but it was talking about things he hadn’t really talked about in this way. It was a real pleasure to do those sorts of interviews with people.

Tom:

I would say beyond Vito, the two Nelson brothers – probably Gunnar the most. He’s another one who is hilarious. Those dudes are so clear-eyed about their career and funny. When you’re doing a book like this, if somebody ends up being both informational and entertaining when you’re doing an interview for a book like this, you’re like high-fiving yourself while you’re doing it because you’re like, “All right, that book is gonna be fun.”

Gunnar explains when they were trying to get their record deal, they would go to [legendary A&R executive] John Kalodner’s office. Every time they would go in, they would play him three songs. He would be like, “That song’s pretty good, these two songs suck,” but they wanted to get those songs on the record. So, they would take the one song that he liked, but they realized he never remembered what they played him, so they would just keep bringing the songs back. Because he’d always pick one that was good and say the other two sucked, they eventually got all the songs on the record.

Honestly, the entire band Vixen was hilarious; they were great. I highly recommend it, if you’re a person who interviews bands, because they’re gonna crack you up. They’re so down to earth and really open about how everything was.

To final answer your question, I think that of all my interviews, Jay Jay French [Twister Sister] has my favorite line in the whole book. He’s talking about Twisted Sister not getting signed early on and everyone turning them down and how they had a chip on their shoulder. He goes, “Just because people say you suck doesn’t mean you don’t suck.”

Andrew:

Corey Taylor [Slipknot] wrote the forward for the book, which sets the tone while providing a clear-eyed, fresh perspective. What was the thought-process behind that decision?

Richard:

Well, Tom and I actually went through a few different ideas of who might be good to write a forward for this book. We didn’t want it to be someone from the era, because, for starters, there’s so many voices from the era who are already in the next 500 pages. We were like “Who is somebody that really appreciates this music but comes from a different world and could give a really great perspective?”

We had a couple of other guys in mind, but Corey really seemed like the guy to go to, because we knew that he liked this stuff. I’ve interviewed him a bunch of times in the past and I think Tom talked to him as well. But, I think one of the things that sparked it for me, is that I saw at one point – and I’m paraphrasing what the tweet was – but he tweeted something about attempting to sing a Dokken song and blowing out a testicle trying to hit a high note. I think Don Dokken might have even responded to him on Twitter, it was this funny little back-and-forth banter. That sort of clinched it for me that he should be the guy.

Tom, because he had been the editor of Revolver, and Revolver was such a huge Slipknot booster in the early days, had a relationship with that camp. So, we got to talking, and Tom reached out to the camp. We sent Corey an early draft of the book, he dug it and said, “Yeah, I’m in.” He penned that forward, sent it back to us and that’s what’s in the book. Those are his thoughts and his feelings.

Andrew:

The 80s music scene was fueled by excessiveness, over-the-top antics, and a vast assortment of shred guitarists. Once the decade turned, many of the revered guitar heroes suddenly became irrelevant in a sense. Talk about the rise and fall of the shredders.

Tom:

We interviewed our old boss, Brad Tolinski about this and tried to get some answers. The shredders themselves admit it — Vito even says it — “It got to the point where like I’m sitting there and it’s like, ‘Oh, there’s Reb Beach [Winger]; there’s Nuno Bettencourt [Extreme].'” They all were under this pressure to outdo the next guy. A lot of them admit that at a certain point they’d reached the ceiling of where, at a certain point of virtuosity, it’s not going to fit the music anymore. These guys had gotten as good as they could possibly get.

What Brad Tolinski from Guitar World Magazine argues in our book, is that what may have taken the air out of the shredder thing wasn’t Nirvana. He said basically what happened, is once Slash came about and was in the biggest band in the world, people who realized they could work every day of their life – to be as good as Nuno Bettencourt, Reb Beach, or Vito Bratta, it’s a combination of hard work, skill, and innate talent. It’s like being a top-level athlete; these guys work harder than everybody else, but there’s also a level where other people could work that hard and never get there. I think that once Slash came out, people had a sigh of relief and were like “Oh shit, I can be a normal guitar player and make it.”

I think it had run its course, like a lot of things in this music. It had reached the epitome of awesomeness and popularity and then begun to devolve into a bit of excess and self-parody.

Richard:

Reb Beach tells this story where Winger puts out their third record, Pull, in ’93. He’s seeing that the tide is turning. He’s aware that it’s not 1988-89 anymore, but they have a pretty good track record. He buys a house in Florida, and tells the family, “Come on guys, pack up, we’re moving to Florida!” He said, “I lived in that house one month and then I had to sell it. It was over.” He had his own guitar model with Ibanez, which I actually bought at the time, and said Ibanez dropped him. It was like everything else you hear about this music with how quickly it all turned; it was that complete as far as his financial picture, even. It was just like, “Done. Pack it up. It’s over.”

I agree with Tom about all the Slash stuff, and that it was getting a little bit crazy towards the end of the decade. As somebody who was learning to play guitar around that time and loved all this music, it was sort of a sigh of relief, because it was like, “Hey, you don’t have to be Nuno in order to play this music because you’re also never going to be Nuno.” Honestly, as much as I loved that stuff, I also didn’t really want to play like that. I didn’t want to be tapping and all that stuff, and I think a lot of guys felt like that. But, I did want to play like Slash; not that what Slash does is easy, Slash is great, but it felt attainable to go in that direction. Whereas, by the end of the 80s, you had Michael Angelo Batio playing with four guitar necks because now even two is not enough. It’s like, where are you going to go after that?

You don’t necessarily need 100 more Vito Bratta’s, but there’s also really no reason why Vito Bratta shouldn’t be able to continue to exist because he’s great; that was sort of the tragedy of it. You don’t need a billion of these guys, but guys like Nuno, and Vito, and Reb – they’re super talented, guys at the top of their game for what they do. You might not love what they do, but that’s a really elite world that they’re playing in and it’s a shame they weren’t able to continue with it.

Tom:

And Paul Gilbert [Mr. Big], same thing; these guys were utterly amazing players. I can only imagine, if you’ve reached that level of craftsmanship of your instrument, to be told that what you do sucks and is lame must have been almost incomprehensible. You know — the way your guitar looks is stupid, the way you play is stupid; it wasn’t fair that those guys got flushed down the toilet. Luckily, time has allowed them all to come back. They’re probably, in some ways, as popular as they ever were now.

Richard:

What is special about this time, is this 80s type of shred was really the last time we’ve had that kind of insane guitar playing shoehorned into what is otherwise a three-minute power-pop song. You get it all — you get the great chorus, you get the great riff, the hooks. Plus, you get the guitar playing, if that’s what you love. I don’t know that it has existed since, and I don’t know that it ever will again in that way.

Andrew:

When the decade expired, many esteemed bands from the era were seemingly extinguished overnight. Do you attribute the drastic musical shift solely on the emergence of Grunge?

Richard:

I think that the music probably would have run its course anyway. I think that Grunge, and certainly Nirvana, maybe hastened it. When you read your book, you see a lot of these guys, they put some blame on Nirvana, but I also think Nirvana is sort of a placeholder for the shift towards Grunge.

A lot of these guys talk about the fact that by 1989, 1990, and 1991 – there were a lot of copycat bands out there. In the early 80s, you had bands like Motley and Ratt, and then before that, Twisted Sister and Quiet Riot – they’re pulling from earlier influences. Whereas, by the late 80s, you have bands who are influenced by Mötley Crüe, by Poison, and by Ratt — who are still in the prime of their careers. And because of this very tight loop, it causes a lot of these bands to sound and look the same. By ’89-’90, a lot of these bands also aren’t doing their best work anymore.

Fred Coury from Cinderella is one guy who says, “Yeah, a lot of us were on our third or fourth album. They weren’t our best records.“

He would point to Cinderella, Warrant — whoever — straying from what people loved about them, to begin with. So, there’s all of that going on, in addition to the obvious change of the guard. No music that is that intensely popular for that many years is going to last forever.

Tom:

Every genre like this has a cycle. If you were to make a list of the 50 best records of the era, there’s not going be a lot of them that are made after 1990. Cherry Pie by Warrant and [Mötley Crüe’s] Dr. Feelgood are probably going to be the last ones in the door on the list of last great records of the era. On a lot of levels, creatively, it had run its course; it had a nice, ten-year run.

Did Grunge have something to do with it? Yes. But, that does not explain why it ended, but how it ended. Instead of it sort of petering out, it was done overnight. It was done overnight to where the producers who worked had worked on this music couldn’t get jobs. The A&R people who had worked on this music were fired.

Brian Forsythe, from Kix, explains in the book that around 1992-1993 he auditioned for The Wallflowers because there was a guitar spot open. Even though he had been in Kix, who had a No. 9 Billboard hit and a platinum record, he didn’t even say he was from Kix.

So, why it ended is a combination of a new genre coming in and an old genre running out of steam. But, the fact that the hostility with which it was met – and all the people involved suddenly became completely irrelevant in the music industry – that’s the unique thing about. Literally everybody turned on this music. These bands were playing arenas, and suddenly, they can barely fill a 200-person club. It was disastrous, and that is the unusual and unique thing about this genre. They probably had their time in the sun as long as any genre, but to be cut off at the knees like that — that doesn’t usually happen.

Andrew:

If you had a time machine and could only see one band at full strength in the 80s, who would it be and why?

Richard:

If I only had one shot at it, in the interest of actually doing the right thing, it’s either going to be seeing Motley at the Whisky or one of those early Guns N’ Roses shows at the Whisky. I think I might also sneak out and go see W.A.S.P. at the Troubadour – and hope that I’d make it out alive from that. Tom probably knows that that’s what my dream would be, to be there and see the fire sign, maybe get hit with some raw meat, and just experience that moment in time.

Tom:

I saw Guns N’ Roses at the Ritz, the Hysteria tour, and White Lion at the Ritz, so I’m trying to figure out what I missed. The whole first part of our book is about L.A. in the 80s and the impact of Van Halen on that scene, and the real show that I wish I had seen, would have been Van Halen on the 1984 Tour. I never saw Van Halen with David Lee Roth. Van Halen with David Lee Roth on the 1984 Tour is the one that got away from me.

I’ll tell you what else you’d wish you’d seen – the No Rest for the Wicked Tour with 20-year-old Zakk Wylde. I remember seeing that at the Felt Forum when Zakk was still a beanpole and his technique was still totally flawless. He was still wearing the bellbottoms – he would jump in the air and do a full revolution and land while still playing.

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/