All images courtesy of Reybee PR/Header image courtesy of Alamy

By Andrew Daly

[email protected]

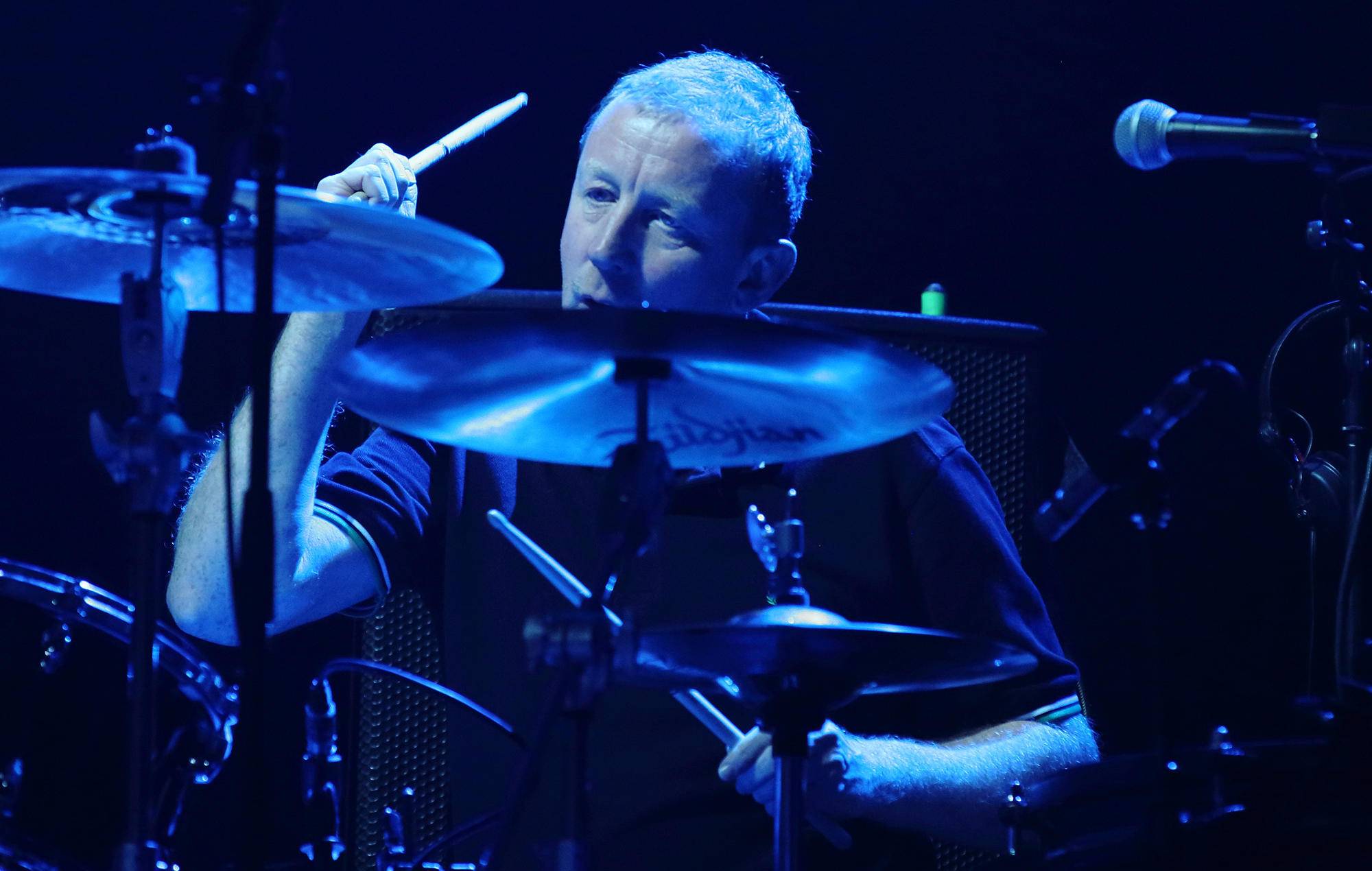

The era of what’s come to be known as “brit-pop” might be nothing more than a bygone period reduced to memory, but drummer Dave Rowntree’s creativity and innovation are anything but.

For Rowntree, his journey in music began at a young age, by way of radio, but not in the traditional sense:

“I had quite a turbulent childhood growing up, as some of us do,” said Rowntree. “But one of the constants in my mind growing up was my relationship with my dad. Where some fathers and sons would go to sporting events together or go fishing together, my father and I used to build radios together.”

With his interest piqued, radio, in all its forms, became a staple in Rowntree’s life. As he grew older, his parents thrust him into piano lessons, which Rowntree immediately hated. As such, the burgeoning drummer had other ideas.

“I thought, ‘Well, if I can get them to let me drop the piano and change to the most obnoxious instrument that there is, maybe they will hate it so much that I won’t have to have music lessons anymore,” quipped Rowntree. “And then I’ll be allowed to go out and play football with my mates.'”

Now firmly entrenched behind the drumkit, Rowntree spent his teenage years perfecting his craft, and after moving on to university, the sticksman joined forces with Damon Albarn and Graham Coxon. With a revolving cast of bassists, the group spent their days gigging around London but found themselves unable to harness long sought-after chemistry.

As fate would have it, Coxon’s bass-playing next-door neighbor, Alex James, fit the bill. With James, a stylish four stringer, who perpetually had a cigarette dangling from his stubble-framed lips on board, chemistry was channeled, and Blur was born.

Initially thought of as nothing more than indie fodder, Blur’s presence on the 90s U.K. alt-rock scene would prove pivotal. With the band’s increased willingness to experiment along with its genre-defying, virtuoso musicianship, fearless attitude, and endless bravado, Blur ascended above its contemporaries.

Retrospectively, the era has many names and carries many stigmas, but one thing is certain – Blur remains at least a notch above their peers, with 2015’s The Magic Whip providing all the proof any doubter might need.

“Historically, making music together has always been an easy thing,” Rowntree recounts. “And when we get in the studio together, or on stage, no matter the time apart, things just fall into place.”

For Rowntree, though, his musical journey extends well beyond Blur, brit-pop, or the late 90s. In the here and now, Rowntree is on the cusp of yet another immense achievement, this time in the form of his soon-to-be-released debut solo affair, Radio Songs.

Serving as an ode to things he loves most, as well as the times, memories, and places that shaped the man behind the album’s electronica, Radio Songs prove to be another harbinger in a long line of divinely surprising moments from an ever-curious hero leftover from that supposedly bygone era.

Rowntree recently took the time to chat with me via phone about his unique relationship with radio, his first musical love, as well as the formation and seemingly endless journey of Blur.

Andrew:

Describe the importance of radio to you when you were young.

Dave:

Well, the title Radio Songs comes from a number of areas. My dad had been a radio engineer in the Air Force when he was a young man, and his job was to teach aircraft pilots how to mend their radios if they crashed so that they could call for help. That’s one of the things he did that he used to be very proud of. But anyway, he used to teach aircraft pilots about radio technology; that was his thing. We would build radios together, and we had a big, long wire antenna in the garden, and we would make these radios huddled around a soldering iron or on the kitchen table. And then, we would connect them up to the antenna and tune into stations from all around the world. And so that was the constant in my life, and it inspired in me a love of electronics and radios that are still very useful.

Also, I had a radio by my bedside, as many kids do. I always have been a terrible sleeper, and I still am. I used to lie awake at night, tuning through the stations from these faraway places, listening to the exotic languages and music from all these stations around the world. And it kind of got me dreaming about travel and kind of imagining what life was like in other places. It was also my political awakening because my father ended up, as many Air Force people did, working for the BBC. And so, my house might have had very conventional politics, you know, conventional center-right politics. We always had BBC News on the TV, and we had all kinds of center-right newspapers around, all of which had a very similar outlook on world events. One night, while tuning the dials, I stumbled upon Radio Moscow. Radio Moscow used to have an English language translation, and maybe they still do, but back then, it was a new service. And while it was clearly berserk and clearly had its own issues – it was as partial as the BBC – but that’s what brought home to me the fact that there’s more than one interpretation of world events.

It never really occurred to me because I hadn’t been exposed to anything more than the conventional U.K. center-right position. It never really occurred to me that there was more than one way I could look at the world. So, even though Radio Moscow clearly had issues, it was interesting, and for me, that was one of those light bulb moments, you know? I found it very interesting because I had all these channels carrying all this information, and all the information I knew and that was being fed to me, that wasn’t necessarily the only interpretation of these events. And that led me to do my own path of personal exploration, which has led me down many political avenues over the course of my life as well. There are other things as well, but that’s sort of what I was thinking of by Radio Songs. It doesn’t just mean listening to tunes on the radio, you know, that’s not what the album’s about. That wasn’t the inspiration for the album, so to speak.

Andrew:

What made now the right time to finally record and release your debut?

Dave:

Well, everything was locked down. Like so many people, it’s always been so difficult for me to commit to doing a solo project because there are so many other things that normally are going on that demand my time or too much of my time. At the moment, a lot of my time is spent writing film and TV show music, and that just takes an enormous amount of time. Sometimes, it takes months, and months, and months. So much so that it becomes a kind of seven-day-a-week job. So, it’s very hard to fit in anything else when you’re doing that kind of thing. And so, you know, writing, recording, and releasing an album means putting money aside for doing that, and it’s quite a time commitment, but lockdown came along. Then suddenly, I found myself with unknown periods of downtime stretching out into the distance. And so, I was stuck in my studio twiddling my thumbs, and my friend, Leo Abraham, who is a producer, he was similarly stuck. When we talked about working together, Leo was also stuck in his studio, twiddling his thumbs. So, we thought we would see if it’s possible to do this kind of a thing by remote control with me in my studio here and see how far we could get making some music together that way. It turned out that it was quite an efficient way of doing it; we’d split up the tasks every morning and then get together every evening and see how far we got on. So, it turned out to be a pretty good way of doing things.

Andrew:

Break down the origins of “London Bridge” for us.

Dave:

The origins of the track are something that I’ve been thinking about very deeply over the years. A lot of the track, frankly, has to do with mental health and where my head has been at, as well many others, over lockdown. It also has to do with the pressures of being on tour and the pressures of trying to hold down a relationship while never being home and all of these kinds of perennial issues. And “London Bridge” is also about when I was a kid, you know, when I was young, there was a weird thing happening to me where the number 126 suddenly seemed to take on incredible significance in my life. I would see the number 126 everywhere, and I lived in house number 126 too. I even got on the 126 bus. Now, I can’t remember any other examples, but it did seem like the number 126 was everywhere and that the universe was screaming the number 126 out and trying to get me to take notice. And I know what that is now; it’s not the universe screaming a number at you. No, it’s actually a well-studied psychological phenomenon called confirmation bias, where you see the things that confirm your ideas and beliefs. With that, you tend not to notice the things that don’t confirm the bias, so when you’re going through life, you get increasingly convinced of the rightness of your ideas and beliefs, and you don’t notice the things that tend to count against them.

So, when I first moved to London, and things with Blur started happening around London, the London Bridge suddenly seemed to take on extraordinary significance. Things tended to happen around there, but it was exactly the same thing, you know, it was confirmation bias at play. But I guess the interesting thing about all of this is that I know what it is, you know? I’m not naive about the workings of the mind, but it’s still a pretty weird and baffling thing. Knowing how it worked and what was going on in my head didn’t make it seem any less powerful. That’s the bizarre thing because you know your own mind, and that was quite a wake-up call for me because of that idea; you know, because confirmation bias exists, you can’t outsmart your mind with that knowledge. This said, you can’t trust your learning to counteract weird tricks your mind is playing on you, either. So, that was quite a significant light bulb moment and quite a significant thing for me to understand. It was just something I had to learn, so that’s what the lyrics to “London Bridge” are about. And that’s the idea that sparked me to start playing with words and write songs for this.

Andrew:

You’re known as Blur’s drummer, which errs more toward alternative rock. This said, your solo album seems to be diverging in a more electronic direction.

Dave:

Well, synthesizers and electronics are where my interest is really at, so that’s what my studio is full of. I build my own electronic gear and sound processing equipment and even designed some bits and pieces myself. So, that’s kind of where that sort of technical side of my music lies because that’s where my interest is. I’ll admit that for a living, I play the drums, but that wasn’t my interest in terms of studio recording; it’s just the instrument I play in Blur. Wouldn’t it be so obvious for me to do some kind of drum thing? I didn’t want to do that because nobody would go, “Oh, that’s interesting. He’s done an album with loads of drums on it.” I felt everyone would be expecting that, so it’s a mind game. You start down a road, thinking, “What is something people aren’t going to expect?” And then you find it, and you say, “What is that?” And then you can go down all kinds of back alleys, and you start thinking, “What if people are expecting me to do something that they weren’t expecting? Then should I be doing something perhaps that they would expect?” So, it becomes a double bluff at play, and you can imagine where that train of thought can get you. I think many people expected me to make a drum album; with this, there aren’t any drums on it. [Laughs]. One of the tracks has a drum kit on it, but overall, it doesn’t have any drums or even drum samples on it. It’s got lots of things that I’ve hit that sound sort of percussive, but by and large, it’s drums and percussion free.

Andrew:

As you move into a seemingly new style of music, what is your approach to composition?

Dave:

I mean, it’s not by mistake that I’ve moved into the realm of synths and things. That’s kind of always been my realm. I’ve always been interested in electronics, as I say, from making radios with my dad to building synthesizers when I was young. You know, my first synth I made myself. So, alongside drums, that’s always been my interest. But, yes, composing-wise, most of the schools I’ve done have been electronic and orchestral. I was going to be an orchestral player when I was young, and my first love was orchestral music as a percussionist. That was the path I was going down until I discovered pop music and girls when I was a teenager, and then I lost my head. [Laughs]. But that’s something I’m still very interested in, and I love an orchestra, and being a drummer in an orchestra is a great gig because they pay you for basically doing next to nothing. [Laughs]. Maybe you’ll hit something every five minutes, or you may not. You’re a paid member of the audience who is sitting right in the middle of the orchestra next to the basses, which is the best place to be in an orchestra.

So yeah, I’m very comfortable writing music. So, when I write for strings, there are no issues. Now, do I get how that works? No, not really. How do I do it? I have no idea. And that’s a terrifying thought about composing for film because I have no idea how I do it. [Laughs]. Every time I sit down to write music, I have no idea what I’m gonna do. I just have to do it. Luckily, every single time thus far, I’ve managed to do it quite successfully, but there’s no technique. You’ve just got to keep working at it and kind of keep experimenting, and it’s a difficult gig because, first off, you’re writing from pure emotion, so you have to capture the emotional journey of the scene in music perfectly. And second of all, it’s when somebody else says it’s right; you know what I mean? The music is right when the director says it’s right. So, it’s a very different discipline, and it’s hard. If I had a technique for you, that would probably make it much less scary. It might not be much more interesting, but it would be much less scary. There are these times when I’ve got to sit down in front of the keyboard and just make music. For half an hour, it’s awful, and nothing works, and then I go, “Oh, yeah, that bit from that thing I did yesterday, yeah, that might really work here,” and then I’m off and running.

Andrew:

Given your interest in electronica, and orchestral music, what first led you to pick up the drums?

Dave:

My parents were classical musicians, so they insisted that I have piano lessons from the age of five to six. I absolutely hated it. I hated it more than I’ve ever hated anything in the entire world. [Laughs]. It was really that I hated the lessons rather than the piano itself because I’ve come to love the piano later in life. But anyway, the lessons in those days were incredibly dull affairs, where they just teach you scales for years. You teach the player these scales and arpeggios over and over again because they’re trying to lay the foundation for your career as a concert pianist, which of course, you’re never going to use.

I knew I had to get out of it, and I wanted to get my parents off me playing an instrument altogether, so my first instrument after the piano was the bagpipes, which probably is still the most obnoxious instrument known to man, especially when played by a ten-year-old boy. [Laughs]. But with the bagpipes, it’s a very physical instrument. The bagpipes are a military instrument for fighting people to play, and at ten, I had nowhere near the physicality that it took to play the bagpipes. So, I thought, “What’s the second most obnoxious instrument?” And unluckily for my parents, but luckily for me, I fell in love with the drums immediately with a passion, got utterly obsessed, forgot all about football, and spent every waking moment I could playing drums for many years.

Andrew:

How did you first meet Damon Albarn, Graham Coxon, and Alex James?

Dave:

Graham is kind of the hub of it all. Myself, Graham, and Damon all lived in the same small town in the East of England called Colchester. Back then, Graham and I played in bands together, and Graham and Damon played in bands together as kids too. And when we all got to university age, Graham and Alex lived next door to each other while they were in their first year of university. So, it was Graham who introduced me to Damon, and it was Graham who introduced Alex to Damon and me.

Andrew:

Is that when Blur initially formed?

Yeah. So, when our bass player left, that’s when we asked Alex to join. I’d say that was the start of Blur, you know, it really began when Alex joined. When the four of us got together, the chemistry felt right, and things were immediately much better than they had been before. Because before that, we had a whole string of other bass players, other guitarists, and all kinds of things. It’s funny; Graham was actually a saxophone player in the early days. I think Graham found the guitar too easy; I think he liked to challenge himself. But once our guitarist left, Graham reluctantly picked up the guitar and decided to carry on doing that. And then, because the old guitarist had left, the bass player decided he had to go with him, and they formed a rival band. [Laughs]. So Graham said, “I have another bass player. I live next door to him. Come along, let’s go see him,” and that was Alex. As I say, chemistry is the most important thing about being in a band, as with so many things in life. When Alex joined, suddenly, that magical chemistry happened, and Blur was signed within six months.

Andrew:

Blur became known as a band willing to push boundaries and experiment, but what was the vision early on?

Dave:

Ah, you’re asking me what was going on thirty or forty years ago. That’s tough to recall. What was our initial vision thirty years ago? You might need to rewind the clock and ask us. [Laughs]. Well, I don’t know, but I can say that it was a very different musical landscape back then. The guitar bands weren’t in the charts; nobody was interested in that over in the U.K. It was assumed that bands like ours would, well, I’ll put it this way; there was a special chart for indie bands like ours because we couldn’t graze the mainstream charts. We were the poor cousins of grown-up music, and everybody assumed we might have some minor indie chart hits. As it turned out, things didn’t work out that way, did they?

Andrew:

Can you recall Blur’s first gig?

Dave:

Yes. That would have been The Railway Museum near Damon’s parents. I think we were having a birthday party in this Railway Museum near where he grew up, and they had this engine shed which you could hire out to have parties in, and we played in one corner of that. We’re talking about over thirty years ago, but I recall us doing quite well.

Andrew:

Blur is often lumped in with the “brit-pop” era, with bands like Suede, Pulp, and Oasis. Looking back, did the members of Blur find it troublesome to boil yourself down in that way?

Dave:

Well, that term was developed much later, as far as I remember. The idea that all of these very different sounding bands formed some kind of scene was, I think, bolted on in retrospect. At the time, we weren’t trying to be part of anything; we weren’t trying to do anything like that at all. Back then, we saw all these other bands as terrible because, to us, all other bands were terrible. We looked around, and we thought, “These bands are hopeless. How are they even selling any records?”

Andrew:

To that end, was the feud with Oasis all it was made out to be or overblown by the press?

Dave:

It was a mixture of both. I think there was a genuine argument that kind of boiled over between two people. And then, I guess that boiled over into a spat between the two bands, Blur and Oasis, but Oasis wasn’t the first band we picked a fight with. We picked a fight with all the bands, really. That was kind of our thing at the time, to say how terrible everybody else was. We used to go on about how useless and wretched all other bands were, but that’s what all those bands did in those days. This was the 90s, and it was very different. Now, we have to say how lovely everything is and how grateful we are to be doing whatever it is we’re doing. In the 90s, in the U.K., there were weekly broadsheet music papers that needed to be filled with gossip, and everyone was desperate for it. And pretty much everybody in a band wanted to be in those, so they were desperate for any gossip and juicy bits.

So, we would have our various spats with everybody, but we’re encouraged to do that. We were encouraged to fit right into that and to fit into the music industry’s demands at that time. Sure, it’s very different now, but all the bands were doing it back then. Looking back on it, we were innovators with the whole thing, and we famously did it because it made national and international news. We even had the crazy idea of releasing our single “Country House” on the same day as Oasis’ “Roll With It” to see who was best, which is a ludicrous thing. [Laughs]. But it captured the zeitgeist, and I think at the time, it propelled both Blur and Oasis into the next level of our careers. But also stapled both bands at the hip to the point where, and I’m sure it’s still true for them too, I still get asked about it decades later. You know, even decades after we’ve all made up, and we all accepted that other bands could make quite good records after all. But we probably wouldn’t be where we are today without having had that idea.

Andrew:

Modern Life is Rubbish, Parklife, and The Great Escape represent watershed records of that era. How do you measure their importance to Blur’s trajectory?

Dave:

Well, certainly, Parklife was a big one for us. That was the album that propelled us into the mainstream. That album took us from being this small indie band who couldn’t get arrested to suddenly playing big venues worldwide. Modern Life is Rubbish set the tempo for that, you know, what was to come for us with Parklife, but once Parklife came out, I mean, you could say that was the start of our professional career. That was the one that we won lots of awards for, and we became these sort of household names in the U.K. after that. So, that was the beginning of that, really. And The Great Escape, that one came out next, and it was just craziness because you had all these bands competing and going back and forth in the papers. It was a big one too, but Parklife was the one that meant the most in terms of growth.

Andrew:

Which one are you most partial to?

Dave:

Honestly, I don’t listen to my own music, so I’m the wrong person to ask. I don’t sit at home and play my own records. That way lies madness, you know? [Laughs]. So, you’d have to ask somebody else. I think I’m just too close to it all. It’s very hard to listen to music you’ve made without kind of hearing the music being made rather than hearing the resulting music.

Andrew:

What pushed Blur to resume activities after the band’s long hiatus in the mid to late 2000s?

Dave:

Well, we went on hiatus because Graham left. We tried to limp on without him, but it wasn’t the same, so we decided to stop. There was never any official breakup, it was just that after Think Tank, and the tour we did without Graham, we just never really picked it up again. Honestly, there wasn’t much enthusiasm for picking it up again without him. But then, around 2009, the issues with Graham were resolved, and Graham was back in the fold. And then we got offered what seemed like a really fun thing, which was they were starting a series of gigs in Hyde Park, and they offered us a chance to headline the first one of those. After that, people kept offering us fun and exciting things that we couldn’t say “no” to. So then, we got to 2012, and they offered us the London Olympics, well, they offered us to headline the party at the end of the Olympics. Of course, we couldn’t say no to that. It’s just that when we got back together again, all these things began to happen. Once you start saying “yes” to things, people start offering you increasingly interesting and fun projects. So yeah, we’ve been together periodically ever since.

Andrew:

What was going through your mind as those first concerts began and you were set to be on stage with your old friends and bandmates again?

Dave:

To think back on it, I guess I just assumed it would all be very easy. And then, on the day before the first set of rehearsals for our comeback tour were to begin, I was listening to the radio in bed one morning, and Stewart Copeland, The Police’s drummer, came on. He had just done a similar thing with The Police, where they got back together, went out on tour, and said, “It didn’t work. It was like getting out an old jigsaw puzzle, and all the pieces had warped and changed shape in the drawer, and now the jigsaw puzzle really no longer fit back together again. It was terrible.” I said to myself, “Oh, my God, we’re absolutely screwed if that’s true for us.” I got up, and I was wondering, “What if we get to rehearsal tomorrow, and it doesn’t work?” Of course, we got back into rehearsals, and by the end of the second day, we really didn’t even need to rehearse anymore. So, we stopped rehearsing and went and wrote some more music instead, which became the “Under the Westway/The Puritan” single.

Andrew:

Blur’s most recent album was 2015’s The Magic Whip. Is there anything new in the works for the future?

Dave:

Yeah, we would definitely like to get something done. The willingness is there; it’s the practicalities that are difficult at the moment. We’ve been saying this for a long time, you know, we planned to do something, but then COVID got in the way of all kinds of people’s plans. Things are still difficult, but we definitely want to, and we do enjoy playing together. So, it’s not a matter of if, it’s only a matter of when, and you know, that’s what I’ve always said anyway. I’ll tell you this; people will know when Blur is over because we’ll announce it. We won’t keep it a secret. So, Blur is definitely not over, but what’s going to happen next? I don’t really know. And when it’s going to happen? I don’t really know that either. But the willingness is there; I’ll tell you that.

Andrew:

Until recently, when Jarvis Cocker reunited Pulp, Blur was more or less the last remaining band standing from that era. To what does Blur owe its longevity?

Dave:

Just sheer bloody-mindedness, I think. And also, good songs and a willingness to experiment with things. I mean, Damon, Graham, Alex, and I are all excellent songwriters, and we do that well together. We try to make everything we do differently from the last thing we did. We did that, and we do that so that people can never quite know what they’re gonna get when a Blur album is announced. We do that, which usually means people are always excited about what’s coming next. In my experience, tenacity counts for almost everything in music and success in the music industry. I’ve found that people that stick at it and don’t let all these kinds of setbacks knock them down they’re the people that tend to succeed in the long run, and in Blur, we are nothing if not tenacious.

– Andrew Daly (@vwmusicrocks) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at [email protected]