All images courtesy of Ken Stringfellow/Getty Images

By Andrew Daly

[email protected]

Power-pop auteur, Ken Stringfellow’s impact on indie music over the last 30 years is evocatively everlasting.

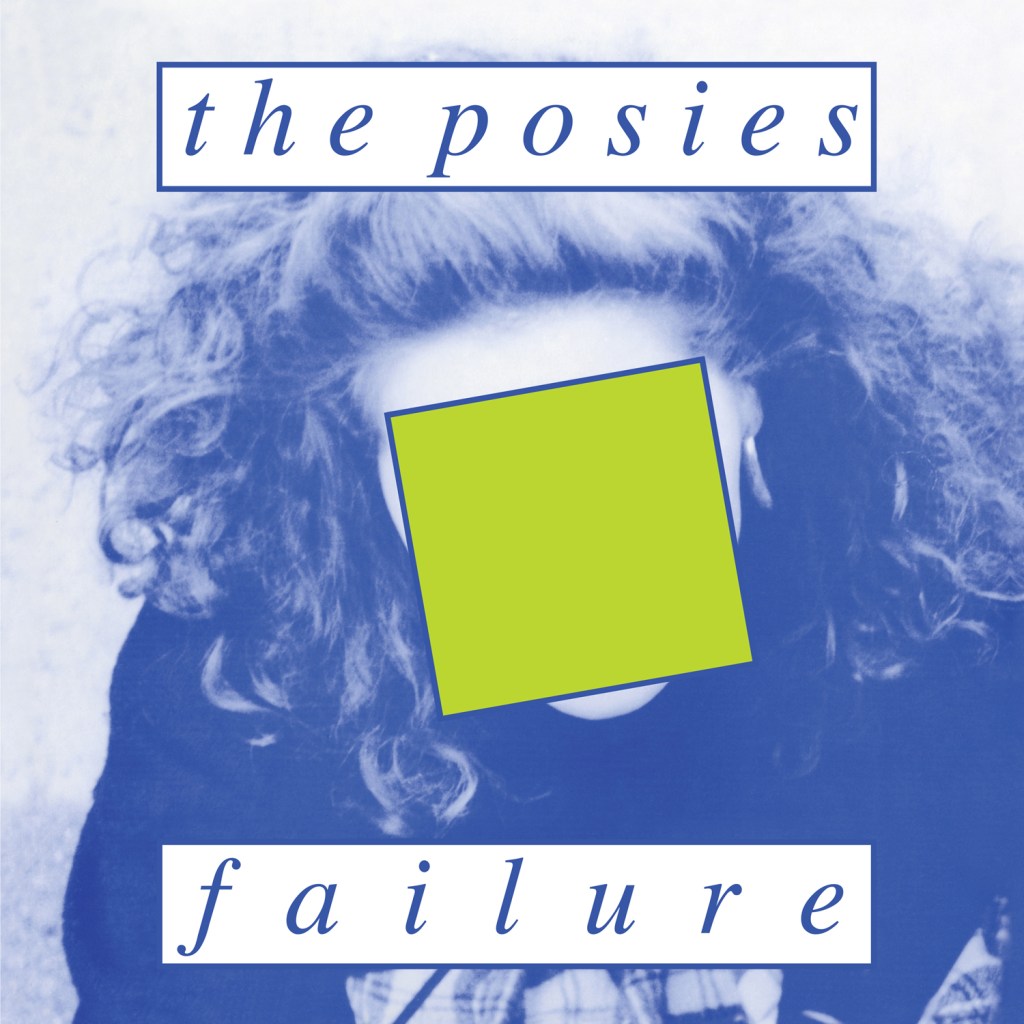

Though initially born in Hollywood, California, Ken Stringfellow’s musical roots can be traced back to a bustling Seattle scene. Amongst the early rumblings of grunge and alternative rock, his flagship band, The Posies, began to steadily garner a robust following in the wake of the surprise power-pop smash, Failure (1988).

While one might have initially thought Stringfellow and his cohort Jon Auer one trick ponies, with seemingly relative ease, The Posies bettered Failure with their sophomore affair, Dear 23 (1990). And as their critical acclaim and cult following began to merge into a steady commercial following, the duo was hand-picked by idol Alex Chilton to round out a revitalized Big Star in 1993.

Through the years, in addition to The Posies, Big Star, and R.E.M., Stringfellow has left his fingerprints on hundreds of records as a producer, solo artist, songwriter, session man, and more.

As Stringfellow embarks on the next phase of his music life, the veteran musician took a moment to reflect back on his long career, as well as the personal and professional journey that has shaped him to this point and beyond.

Andrew:

What first sparked your interest in music?

Ken:

In the environment I grew up in, the seemingly complacent but deeply unhappy suburbia of 1970s America, I dreamed that there must be more to life than that bleak atmosphere. I have always felt like an outcast – indeed, being an adoptee, one is rather destined to have this notion. We moved frequently. There was very little for me to attach to in my immediate surroundings, and records seemed to speak most directly to me because they spoke in terms of feelings. We’re talking about my parent’s record collection, starting from, say, age 4 or 5. It gave me a glimpse that a more colorful, loving, and interesting world was out there to be discovered. That it was OK that I didn’t fit in; it was not that I was failing to integrate; it was that the environment was failing me, and a more like-minded community might be found out there in the wider world.

Andrew:

What was it about the guitar that initially drew you in?

Ken:

I actually started on piano. When my parents saw how absorbed I was in their record collection, they encouraged me to take piano lessons, starting at about age 9. Guitar came later; I was already in bands starting at age 11 and listening to rock music; it seemed the guitar was more in step with what I was hearing than the piano, and lo and behold, my stepdad actually had a guitar – he didn’t play, so it was free to be used.

Andrew:

People often talk about other players’ influence, but what life experiences shaped your sound most?

Ken:

As hinted at above, I was a very lonely person. Moving all the time, it was hard to make friends. My parent’s divorce was devastating. As an adoptee, I now understand that a feeling of ‘otherness’ is very common to us, but I just experienced it as a fearful, isolating difference that I couldn’t understand. So, that feeling of being different has always been my guide. I am more comfortable now with being unique, as certainly it’s true that everyone is unique (even if some people are more conformist than others, and there’s nothing wrong with that). But that feeling of being misunderstood and alone motivated me to cry out, as it were – and we call that cry ‘music.’

Andrew:

Take me through the formation of The Posies.

Ken:

I met Jon Auer in 1983 when I was a freshman in High School, age 14, and thus Jon would have been in 8th grade, age 13. He joined a band I was in. His talents at that age were really impressive – and we gravitated towards each other, I now believe, as we both had a bit of that depth that comes with having seen too much too young. We did not have stars in our eyes, which set us apart from our musical colleagues at that time. We needed to express deeper feelings in music, and our connection, which developed once Jon arrived at High School the next year, was based on mutual support of this expression.

We experimented with many kinds of music, trying different things, and found through experimentation the kinds of qualitative aspects that make a great song, be it a folk song or a synth-pop song. Melodically, lyrically, and emotionally – all great songs have a certain commonality that makes them endure. This was the ethos under which we began The Posies. We had a break when I went to university in 1986 and thus left town, but by the end of that school year, we were comparing notes and demos that would end up being the songs on our first album.

Andrew:

Can you recount The Posies’ first gig?

Ken:

We made the album first. We played a couple of acoustic shows debuting some of the songs while we were making the album, but really, we made what we thought was a long-form demo and were encouraged by our friends to release it as an album, which we did, as a self-released cassette in the spring of 1988. Amazingly, it was picked up by a local commercial radio station, and basically, we went kind of viral in a pre-internet way. Out of nowhere, we had airplay, fans, and reviews. It was unexpected and totally exhilarating.

So, we had to scramble to find a band as we were being offered shows; as it happened, a classmate of mine at the University of Washington, Arthur ‘Rick’ Roberts, played guitar and had a roommate, Mike Musburger, who was a drummer, and they had a rehearsal space in their house. Arthur agreed to play bass, and within days, we played our first gig in May of 1988. Things grew very fast, and by the end of the year, we could play to about 1000 people if we had an all-ages show in Seattle. All I can say is that it was happening so fast that it was impossible to do anything but just scramble to stay on top of it. But it was also really, really fun.

Andrew:

What made PopLlama Records the right label for The Posies?

PopLlama is where we wanted to be, even before all this. We loved the Young Fresh Fellows, the Fastbacks, The Walkabouts, the Squirrels, and Jimmy Silva; our dream was to be among them. In fact, Scott McCaughey of the Young Fresh Fellows, who was someone we admired greatly, was essential to our early success — he gave us our first review (in the local music monthly The Rocket) and our first gig. He’s a wonderful human being, and you and I wouldn’t be speaking today if it weren’t for him. So, since he took an early interest in the band, he helped facilitate our move to PopLlama, who gave Failure a proper release on LP and, eventually, CD.

Andrew:

Failure is an enduring classic. How did the album come together?

Ken:

At one point, those abstract ideas about songwriting and what makes a great song weren’t exactly a great sales pitch when we were looking for musicians to form a band. Most people we met were set on making a clear stylistic choice – goth, postpunk, etc. – and building a band around that, and we didn’t know what our style was going to be yet. We had songs and influences, but we felt it would make more sense if we made demos, and thus we could flesh out how we wanted to sound and discover it along the way.

Amazingly, Jon had built a home studio with his father, something quite professional for what’s essentially a garage studio. It was small but well-equipped, and Jon had learned drums, so we had all we needed to make the album. We did one song in the summer of 1987 as a test run and then starting over the Christmas break 1987-1988, and on weekends over the next couple of months, I would return to our hometown of Bellingham, and we’d record at Jon’s house. We did some of the drums at the local university (where Jon was enrolled) since drums interrupted Jon’s parents’ TV nights! We played everything ourselves. Jon played drums; I played bass, and so forth. It’s recorded on analog tape (there were no other options then). We self-produced because we had songs, a studio, and time, and there were no other options.

Andrew;

Walk me through the writing and recording of “I May Hate You Sometimes.”

Ken:

It’s as described above. Jon wrote it, so I can’t speak for the composition. As we tended to wear our influences a bit more on our sleeves at that time, it sounded to me like Jon making his best go at an Elvis Costello song (see also: “Ironing Tuesdays” with me trying to write my best Colin Moulding song, with a domestic scene that Squeeze would have been able to conjure).

The recording was like I described – we did drums at Fairhaven College since they had the same tape format as Jon’s studio. Weirdly enough, we didn’t think to record a scratch guitar. We simply fed a click to Jon’s headphones, and we both *imagined* the song in our heads; I would occasionally speak into the talkback, “Here Comes the Chorus…” or something like that. I have no idea why we didn’t do the obvious and have Jon play to a guide guitar and vocal, but in any case, he had the arrangement in his head.

Then we did the overdubs at Jon’s and filled up the 8-tracks. We bounced those 8-tracks of instruments to a very high-quality cassette, and put that submix back on the 8-tracks, so we had room to do 6-tracks of vocals and percussion. So, when Jon mixed the album, there really wasn’t much to mix – just the vocal mix against the backing track. He mixed the album in one all-night session. The master is again a high-quality (dbx encoded) cassette tape.

Andrew:

Dear 23 is perhaps even better than Failure but doesn’t get the same amount of attention in retrospect.

Ken:

To be fair, it sold much more, had a video on MTV, and glowing reviews (check the LA Times comparing it to Abbey Road!). But, of course, it doesn’t have the same homespun backstory as Failure, so it was no longer a “little record that could.” Being a big-budget album by these two wunderkind songwriters barely of drinking age, expectations were considerably higher, so harder to meet. Whereas Failure had no expectations, no one saw that one coming, and thus, just by existing, it exceeded expectations! We didn’t feel it was challenging to follow Failure because we knew the next batch of songs was great, the band was a great live band, etc. We could have benefited by trying to meet the marketplace a little bit, this kind of ’60s thing that the album has was not really in line with where music was going in 1990, but everyone, including the label, believed in us.

Andrew:

What led to the shift to DGC Records? Did they instigate working with John Leckie as producer for Dear 23?

Ken:

We were a band with a big following in Seattle that had achieved radio airplay on our own. We had every label knocking on our door. Geffen was the label that released XTC in the U.S. Need I say more? In fact, we requested John Leckie for his work with XTC and the wonderful Dukes of Stratosphear albums. If anyone could make the songs shimmer with old-school trippiness, it would be John. He’d just had a big success with the Stone Roses, so the label was on board. Having said that, we didn’t give John much room to maneuver, but he brought an excellent engineering sense and a spaciousness to the recording. We had a lot of ideas that we wanted to execute; we probably kept him busy with that.

Andrew:

How do you measure The Posies’ influence over the power pop and indie scenes that burst open in the 90s?

Ken:

Honestly, I have no idea. Probably not that influential. I see elements of a similar sensibility as ours in the sensitive, literate bands that came later, like Death Cab For Cutie and the Long Winters.

Andrew:

You were integral to the Big Star reunion. How big of an influence was Big Star on The Posies?

Ken:

They certainly had a significant influence on us; once we heard them for the first time when our first album came out and drew comparisons to them, we were hooked. The story has been told many times, but in a nutshell, two college radio DJs from Missouri proposed that Big Star reunite for their spring concert in 1993. After nearly 20 years of saying “no thanks” to reviving Big Star, Alex Chilton agreed. The problem then was that Big Star as a complete band had been in tatters by the end of their original run. Founding member Chris Bell had been dead for 15 years, and Andy Hummel simply wasn’t interested at the time.

So, the search for who could fit the bill to round out the lineup commenced. Many bigger names – Mike Mills, Paul Westerberg, Matthew Sweet – turned it down, either for schedule reasons or simply by being intimidated by the pressure of reviving a legendary band and not wanting to be associated with less-than-stellar results. Jon and I, of course, were not well known, but we were absolutely agitating for the part and just knew we could do the parts – especially the vocals – justice. And Jody Stephens agreed and nominated us for the roles.

Andrew:

In Space served as Big Star’s fourth and final album. What are your memories of its inception?

Ken”

It was very simple; we gathered at Ardent Studios in Memphis, where all of Big Star’s original work was made, and each day in the studio, someone would present a kernel of an idea or, perhaps, a nearly finished song. We’d spend the day developing it, getting a live backing track, overdubbing vocals, and such. We did two one-week sessions like this. So everything was written in the studio or on the fly during the hours outside the studio.

Andrew:

After working with Alex Chilton as closely as you did, how do you best measure his influence?

Ken:

His influence on me, or music in general? In general, Big Star presented emotionally honest music that did not subscribe to the larger-than-life mythology that predominated ’70s rock nor to the playful theatricality of glam rock. In that sense, they were a precursor to the emotional honesty and accessibility of indie (versus mainstream) music today. They speak to you, even across the decades, like real people you would know; I love Led Zeppelin, but there are very few vulnerable moments in their music, and there are a lot of Hobbits and such. It’s fun but not exactly relatable.

For me, Alex showed me how much unnecessary second-guessing and polishing we musicians tend to do rather than let a musical moment be what it is. Especially now, with the computerized way we make music, where everything you hear has been aurally Photoshopped, so to speak. He knew the unintended moments were important; not everything in music has to be under the musician’s control. It is better when not completely corralled by the musician’s desire for perfection. I sweat the details much less than I used to in the studio, and I have Alex to thank for that philosophical approach.

Alex was unapologetically himself, which of course, made many people dislike him. He was “difficult,” they would say, which really means he didn’t bend over backward to make everyone happy on their terms, but he assumed the integrity and dignity of his own terms should also matter to people. When you’re a famous person (remember Alex was a massive pop star at age 16), everyone looks at you as a means to their ends and assumes that you have already gotten your needs covered or that your success means you’ve had more than your fair share. They wouldn’t say that if you questioned them, but people’s actions support my observation—a good lesson to learn. Alex was true to himself at all times.

He was comfortable with saying “no” to people. I never knew him to lie or cheat. At the same time, if he didn’t feel like being pleasant or social, he just didn’t do it. Americans especially value a pleasant exterior; we put more value on that than we do on how people actually are on the inside. Truth is kindness, whether it’s pleasant or not. And Alex lived like that, and I also have taken to heart and operate from the principles he lived by.

Andrew:

Do you feel your era of Big Star stacks up against its ’70s heyday?

Ken:

I think we did justice to the live performance of the vintage material. And we were happy to follow Alex’s curveballs and explorations. So, the fans were happy, Alex was happy, and thus, I’m content with my contributions.

Andrew:

You played an important role in R.E.M.’s later period. How did you become involved?

Ken:

I played a number of instruments; there was a lot of instrument switching. In a typical show, I would play keys, guitar, bass, percussion, accordion (OK, that’s kind of like keys mixed with CPR), and backing vocals. On some recordings of R.E.M.’s, I’ve even played drums… and trombone (not well).

When R.E.M. recorded Automatic For the People in Seattle, Peter Buck ended up staying on, having met his future wife during the sessions. Remember when I talked about Scott McCaughey earlier and how much he did for the early Posies? Well, Scott is a central figure in many musical lineages. Via his work as a journalist as well as a touring musician, he had become friends with Peter over the years. I see them as almost brothers, really. When R.E.M. came to Seattle, Scott was already a friend to Peter, and it was the owner of the club Scott was booking at the time that became Peter’s wife. I was a regular at that club, The Crocodile Cafe.

In fact, The Posies were the band that played the club’s opening night in 1991. So, as the Croc became my hangout, and Peter’s, and Scott’s… it was something of an inevitability that we all ended up playing together. First behind Scott in his project, the Minus 5. And eventually, in R.E.M.

Andrew:

Can you expand on your role with R.E.M.? What sort of dimension did you bring to the music?

Ken:

When R.E.M. made their album Up in 1998, they had undergone a big change with the departure of drummer Bill Berry. The shakeup led them to explore new ways of writing and recording, which included the presence of synthesizers and other vintage keys. To play that live, they would need a couple of versatile musicians to pull that off. Scott McCaughey had been on board since 1994 as a backing musician. With my ability to switch between various instruments well established in the studio working with the Minus 5, I was brought on board — a huge leap of faith on the part of what was the biggest band in rock at that time.

What did I bring? A lot of enthusiasm. Deep knowledge and love of the band’s catalog. A willingness to experiment and let things get wild, which perhaps a more trained keyboardist might have been less inclined to do. As Miles Davis said: “Anybody can play. The note is only 20 percent. The attitude of the motherfucker who plays it is 80 percent.” I’m not saying my attitude is as badass as Miles’, and my technique is certainly not at his level. But I will say, the spirit in which I approach music, a mix of intelligence and naiveté, fit in well with R.E.M. – they are great musicians not by their respective virtuosity but by their fearless creative spirit. And I aspire to work under the same standards. We gelled.

Andrew:

What did your work as a solo artist afford you that your position in your many bands did not?

Ken:

Freedom. That which I have always sought, really. Sometimes being fearless in your creativity means that you have to stand or fall on your own merits. It’s wonderful to play with established musicians, and to share the stage with so many of my musical heroes/heroines have been a dream come true. Still, if I call myself an artist, I must leave the safety of a journeyman’s trade and take risks myself as my own entity. With my first solo album from 1997 (This Sounds Like Goodbye), I wanted to fully abandon the meticulous way of recording that was The Posies’ studio methodology. My first solo album, recorded at home, is totally improvised; each instrument or vocal performance was one pass (I had 8 tracks to work with). It’s messy, strange, and also unique, and vulnerable.

Andrew:

If you had to pick out one album from your discography that you thought would be more popular than it was, which one would it be?

Ken:

I don’t know if any album of mine was assumed to be destined to be more popular than it ended up being. I am not sure that framing the question agrees with how I look at things. I will say my album Touched is an album that seems to work really well. I think the songs are quite good; I worked with Mitch Easter at his wonderful studio, so the sounds are amazing. And its commercial trajectory was certainly affected by its release date – September 11, 2001. I had a good label behind me and had a tour booked, etc. Who knows? Maybe in an alternate universe, that was a big (big for indie, anyway) album. I am not sure that it matters, ultimately, how big these records are across the board. It’s more about the relationship of the individual listener to the record. Did I connect with people? Did it make them feel less alone, soothe them, and give them a place to bring joy and sorrows? If so, then I accomplished my goals.

Andrew:

Which record that you’ve been a part of means the most to you?

Ken:

There are moments, moments where I really felt I expressed something essential about myself. I think, as artists, that’s what we’re shooting for – posing existential questions about ourselves and our world, and this question can be asked again and again in billions of ways. And the presence of these questions keeps the world honest and human. The questions have no answers. But they need to be there. I can’t point to any one record as being “the” record of my career. It’s like asking what your favorite letter of the alphabet is. They all need to be there; it’s in harmony with everything else that they come to have a purpose.

Andrew:

How do you reconcile the many musical sides of yourself, and which instrument do you identify most with?

Ken:

I’ve played many instruments in all three of my bands. I don’t think those are different musical sides of me, though. I brought openness, a humanistic point of view, a willingness to explore, and some old-school chops to every project. That’s really it. It’s a certain energy, an energy that is motivated by my deep desire for human connection, and performance provides the lightning rod for its expression. So, being present with a lot of passion is, I suppose, my hallmark. I’ve never cared about making a buck, really. I have never been interested in being just a good worker. I am a hard worker, and of that, there is no doubt – my discography is hundreds of albums deep as an artist, band member, producer, mixer, player, and so on. But all that activity has to have a point, more than just paying the bills. There are ways to pay the bills that involve less risk, less sacrifice, less time from loved ones, and less exposure to ridicule and envy. Why do we do it? Because we have to. That’s the only thing I can say about differentiating an artist from a musician. A musician plays because they can; the artist creates because they must. We must ask the questions that no one else thought to ask. Over and over.

Andrew:

What’s next, Ken?

Ken:

I am working on a new solo album now. Having cleared up some of the childhood baggage I was carrying around, I have found that my writing goes deeper, and I’m more connected to my emotional self. We are fractured as long as we have repressed childhood baggage (and virtually everyone does).

– Andrew Daly (@AJDWriter88) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at [email protected]