All images courtesy of Rik Fox

As you examine many of the pivotal moments in Rock ‘N’ Roll history during the 1970s and 1980s, you’ll discover that Rik Fox was often at the center of many of the genre’s groundbreaking occasions.

A talented bassist bursting with style and charisma, Fox initially began his winding career through the industry in several of New York’s most notable acts and made waves amid a vibrant East Coast music scene.

But it was a phone call, the allure of potentially landing an enticing gig out west, and an unwavering leap of faith that fueled Fox’s introduction to what he now refers to as “the rabbit hole.”

Uprooting to the West Coast with nothing promised and driven by youthful exuberance, and determination, Fox auditioned for an opportunity to join Blackie Lawless’s new-look band — a sequence of events that would ultimately alter the course of Fox’s career.

In the first part of a three-part interview series with Fox, we discussed his earliest introduction to music, the New York music scene, his affiliation with KISS, and the origins of W.A.S.P.

Andrew:

Well, Rik, let’s go back to the beginning. What initially gravitated you to the world of Rock ‘N’ Roll?

Rik:

Well, let’s see. In the late 60s, which was kind of a perfect golden era to be introduced to popular music — ’64, of course, was The Beatles and whatnot — and ’65 and ’66, you had a lot of the folky bands starting to become electric and catch a lot of attention. That brought us into the Woodstock era; I think some of the first stuff I was listening to was Gary Puckett & The Union Gap. I thought they were cool because they had uniformity in wearing Civil War outfits; there was no mistaking who they were. As the harder and heavier stuff started to cross my attention, I started listening to that — early Ted Nugent & The Amboy Dukes, Status Quo, Cream — these things were starting to come up on my radar. The first two albums I got when I turned thirteen in 1968, were The Beatles’ Rubber Soul, and the very first Steppenwolf album. So, there are two different, diverse directions of music, and both were attractive. Even at my young age, I was able to understand, lyrically, the content of John Kay’s material in Steppenwolf. I liked The Beatles — and Rubber Soul was a fantastic album to be introduced to — I really just gravitated more towards Steppenwolf. I guess you can say the defining moment was when I saw them on TV, it was either American Bandstand or one of the shows that were like that, and I saw Steppenwolf. I saw their bassist, Nick St. Nicolas — leather pants, buckskin fringe jacket, the white Rickenbacker — and I said, “That’s it! He’s cool. I wanna be a bass player.”

I had guitar heroes; Leslie West from Mountain; Humble Pie; Slade; Uriah Heep; Spooky Tooth. I kind of got a taste of it in high school to what, I guess, being a roadie was like. We would have high school dances, so I got on the dance committee, and you’d show up there on Saturday and rearrange the cafeteria — we had a huge cafeteria — and wall it off with all the folding tables. We’d put crepe paper — blue paper — on the fluorescent lighting. It gave everything kind of like a psychedelic, poor-man’s black light effect. I’d help all the bands roll their gear in, set it up, and I’d hang around there and watch the bands do their soundcheck. The dance would commence, once it got dark about nine, ten o’clock, it was over, and I’d help them fold up their gear and bring it back to their vehicles and I would go home. So, that’s my introduction to that kind of a world.

Andrew:

As someone who lived it, tell us about the New York club scene at that time.

Rik:

Well, that would come later, after I got out of high school in ’74. So, by late ’74 into ’75, one of my many jobs — and this was a popular form of employment in Manhattan — was being a foot messenger; I was a foot messenger for a printing company. We were in midtown Manhattan, and in walking distance to all of the major record labels, walking distance to Aucoin Management — which were the people that signed KISS. We had business with all these companies and whoever was doing advertising. That’s the Madison Avenue area. We did business with a lot of them, so I had reason to be frequenting all of these different places, and kind of made a mental network note of where all these places were and visited them constantly. Even if I wasn’t going to them directly, if I was going to another company in that building, I would always step in to Capitol Records or Electra Records or over at Aucoin Management.

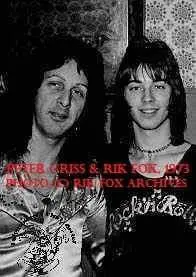

I was sitting outside of the Seagram’s Building one day, it’s on Park Avenue and 52nd street, and a girl came by while I was having my lunch, and she had a haircut like mine — which was what we used to call the “rooster haircut;” the layered haircut, and you kind of stand out as two creatures from the same planet. My first layered haircut was given to me by Peter Criss, and all of those layered haircuts were based on the Paul McGregor — what they called the “shag haircut.” And Paul McGregor was a hairstylist that started over in England and started cutting all the Rock Star’s hair. Rod Stewart has what they called the “rooster cut;” your hair would stick up on top like that, in layers. Ronnie Wood and a lot of the English bands were starting to get that layered haircut look. Then, of course, McGregor came over to America and set up hair styling facilities from New York and Los Angeles. He was cutting the Hollywood stars’ hair; everybody was getting the shag haircuts.

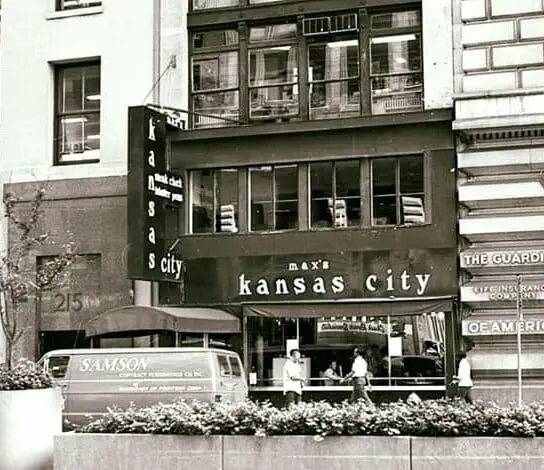

So, this girl recognized my haircut like hers, and we got to talking. She asked me if I had ever been to Max’s Kansas City, and I said, “No, I don’t know what that is.” She was shocked … “You don’t know what Max’s Kansas City is?” … “No, I don’t. This is the first I’m hearing it.” She goes, “Well, I have to show you this club.” … “Okay, fine.” So, we agreed to meet later in the evening, and she took me to this club, which was on Park Avenue South and 17th street, I believe. Essentially, Max’s started out as an artsy-fartsy kind of an art crowd for Andy Warhol, and the type of celebrity people that he hung around with. Little by little, as these art crowds started rubbing shoulders with the music industry, then you have your Salvador Dali, Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Mick Jagger. These people start hanging out at these clubs. Well, that’s of course going to attract and draw more of the music crowd, as well, and Max’s started having bands play there. Aerosmith, Alice Cooper, Bob Marley, Bruce Springsteen, all of these bands got signed out of Max’s and played at this legendary club. It took off, and this is the club that she took me to. That was my introduction, as I say, to the rabbit hole. And it was down that rabbit hole from there, and no looking back.

In so doing, she introduced me to a guy she knew who had a band; his name was Sebastian Black. He went by the name of Sebi Castle back then, and he dabbled in stage magic, fire effects, pyrotechnics, but he also had a band called The Martian Rock Band. We got to talking, and he said, “Well, we’re looking for a bass player.” And I said,”Well, I’m a bass player but I’m still kinda new. I’m not great or anything.” He said, “Well, come to our loft and let’s jam. We’ll try you out,” and that led me to more conversations with him. Meanwhile, we’re watching Debbie Harry of Blondie singing backup for another band there at Max’s. We eventually did a show on the same bill with Blondie. So, this was my first introduction to it.

To answer your question about the clubs, there was Max’s in that area; you had Mercer Arts Center, which was further downtown in what they called The Village; Coventry out in Queens, which used to be called The Popcorn Pub, which was just on the fringe edge of too far of walking distance from where I lived in Brooklyn. And there were various other clubs that were going on in New York for other kinds of music.

Andrew:

Your band, Virgin, became a prominent act amongst the scene shortly after. How do you remember your pathway into the band?

Rik:

After about a half a year or so, The Martian Rock Band broke up, and I found myself working back in The Village, in one of the clothing stores down there. A lot of rockers and tourists would come by into all the stores down there; I would say 8th street was probably one of the most popular streets there, on the West Side, on the corner of 6th Avenue. I worked a couple of doors down from Electric Lady Studios — Hendrix, Eddie Kramer, Zeppelin, and KISS recorded there — so it attracted a lot of rockers to that area. A guitar player walks in with his girl — his wife or girlfriend, I don’t remember — and a conversation strikes up. He’s with a club cover band out in Jersey called Virgin, and their show was doing all the British wave of glam music — Mott The Hoople, Queen, Alice Cooper. We got to talking, and he liked the way I looked. There’s a pattern; people started getting me into their bands because of my look. The playing didn’t seem like the most important thing, it was what you looked like and, “We’ll worry about the playing later” kind of approach. I mean, if you’re competent enough at what you’re doing, the look is what brought the people into the clubs.

So, they set up an audition and I learned a whole bunch of the cover songs. Like I said, I wasn’t that great of a bass player; I was still learning. I never took lessons; I was always like a street player. I’d play along to the records and try to figure out what I was doing. But the singer of Virgin, Ian Chris, he liked everything I brought to the table, and he told the guitar player, “I want this guy in the band. Do whatever it takes to get him up to speed.” So, they would drive from Jersey to my place in Brooklyn, and we’d go over the material down in my basement, or I would take the train over to Jersey and meet them, and they would pick me up, and bring me to their rehearsal studio. So, that’s kind of how I got into Virgin. They had an Alice Cooper show, and he would get a loaner — like an 8-foot, 9-foot boa snake from a girl he knew — so we’d have the snake in the show.

I was highly influenced once the band Angel came out in ’75, ’76 and I got to see what they looked like with their white costumes on Helluva Band, that’s another pivot point. That was a game-changer. I had a similar look to what they looked like, and I went, “Okay, that’s a direction I can work with.” So, I had a white costume made that kind of resembled Mickie Jones’ outfit, and we had the 7-inch platform boots with the big heels and all of that. We were a good draw in the clubs. We played the same clubs as Twisted Sister, and this is before Dee Snider was in Twisted Sister and Harlow. In New Jersey, Harlow was as big as what Twisted Sister was in Long Island; they were like the top drawing Glam band. And we did a lot of the same songs, so Virgin was kind of like Harlow, Jr. We all got to be friends; we all played the same clubs. There was none of that backstabbing, competitive crap that I found when I got to Los Angeles.

Andrew:

As I understand, it was you who subsequently renamed the band SIN.

Rik:

That’s correct. We went as Virgin for a while, and I think at some point, we might have seen in one of the Rock magazines that Bill Aucoin was starting to manage a band of the West Coast named Virgin. We had the name first, but they didn’t know that. But since we were starting to change members, and try to evolve to another level musically — our drummer, who was the brother of the guitar player — he had a nine to five job at a bank or something. He was wearing a wig while he was playing with us, and he’s like, “You know what? I don’t wanna do this anymore. I don’t wanna keep playing until four in the morning, and having to get up two hours later to go to work.” So, we had to get another drummer, and after hanging at Max’s, I had met a drummer named Stan Bassel, who goes by the name Basil Stanley. He knew Gene and Paul, and the guys in KISS from college, and we got along really well. He lived out in Queens, and I said, “Why don’t you try out for the band I’m in?” So, I got Basil into Virgin. Ian and I spent a lot of time talking business, and we said, “You know, maybe we should start thinking about maybe becoming a new band, name-wise.” So, after a short period time, Virgin became Lust, and then within about a month, Lust became SIN. Around the spring of 1977, I came up with SIN. Back then, there was no internet, so there’s no way to check if anyone else was using the name, but we had not heard of anyone using the name. I mean, we looked around, but you’re limited at what you can see, and your scope around the world. And I drew up a logo with a snake, and an apple with a bite in it over the “I.” That’s what we were using, and we played off of the variations of the themes of the concept of sin, in a light-hearted way.

Andrew:

Among the many interesting layers to your career, Rik, is that you were there to witness the inception of KISS. How did you figure into the equation?

Rik:

I was in high school at the time, and Peter Criss’ family moved from Williamsburg, which is kind of the next town over, to an apartment right around the corner from my house there in Greenpoint. Now, Greenpoint was famous for having a lot of bars on almost every corner, and that goes way back to early, early Greenpoint. They moved upstairs over a bar on the corner of Monitor Street and Norman Avenue, and they didn’t have a backyard; their backyard consisted of going out their kitchen window onto a roof, which was over several parking garages. And then they would go up the ladder, to another part of the roof over their apartment, which is where Peter’s father had a coop of pigeons — a lot of old Italian guys would have pigeons and they’d raised the pigeons around and let them out like that. So, that was his hobby. Peter had three sisters; Nancy was the oldest, then it was Joanne, who I dated, and then Donna was the youngest; she was like 17. I introduced my high school neighborhood best friend, John, to Donna. So, John wound up going out with Donna and I went out with Joanne.

We would gravitate towards each other if seeing each other walking around in the street because they were new in the neighborhood, and they didn’t look like they fit in with the rest of the neighborhood. They looked a little different; not in a bad way. So, I started dating Joanne, and they told us about their older brother Peter, who was this Rock Star; I think at that point, he was just leaving the band, Chelsea, that he did an album with. Chelsea was kind of like a Grateful Dead band. Even though it had some Hard Rock elements to it, the way it was mixed, it didn’t come off really hard and heavy. So, Peter was between gigs, he played some of the clubs in Manhattan and whatnot, and one day he showed up there, and I was like, “Wow, this guy really is a Rock Star looking Rock Star.” He had the total Rock Star look; tight jeans, platform boots, the layered Rock ‘N’ Roll haircut. He was married to Lydia at that time; they were living down in a different section of Brooklyn.

There’s the whole famous story of Peter putting the ad in the local papers, and Village Voice, and Rolling Stone, saying, “Drummer willing to do anything to make it.” And that’s how Gene and Paul spotted the ad, and the three of them started to rehearse. So, Peter would invite us up there, he’d say, “You wanna come up and watch? Tell us what you think.” We were like, “All right, cool.” So, we’d pile into Lydia’s car, Peter was driving Lydia’s Chevy Nova, I think, and we’d pile in and he’d take us to the loft there on 23rd street, or we’d take the subway in and take the subway back. And we go up there, and it’s maybe a 12 by 30-foot room, maybe 15 by 30; it wasn’t that big. They were set up on one end of the room, and we’d sit there on whatever chairs or old couch, and we’d sit there, and we’d watch ‘em. I remember seeing a stenciled word on Gene’s SVT cabinet that said: Jack Bruce. So, he actually had one of Jack Bruce’s old SVT setups. We’d never heard music like theirs before; there was nothing we could really compare it to. They were creating their own bar and then raising that bar on a regular basis.

We would watch them rehearse, rehearse, rehearse — three-piece — we didn’t go there during their auditions. The next thing I know, we went up there, and there was this guy leaning against the wall. He kind of looked a little like Shirley MacLaine with a layered, shaggy haircut. He had a grey pinstriped suit on with an orange sneaker, and a red sneaker, or a purple sneaker — he didn’t match. That was Ace Frehley. We watched him pull off these ripping leads that just fit perfectly with what they were doing. Paul was constantly pushing him with his elbow to get him off the wall, kind of like to play with them; body moves. And that was our first introduction to seeing KISS before they were even called KISS.

Andrew:

So, you didn’t get to see Ace’s audition?

Rik:

No. We didn’t go up there for the auditions. I had heard them mentioning Jay Jay French; he auditioned for them. Bob Kulick auditioned — I don’t remember if Bruce Kulick did, but I know that Bob did — but Bob didn’t wanna go with the makeup thing, and the hair thing. Bruce Kulick was playing in Blackjack at the time, with Michael Bolton. But we’d go up there, and my friend John would bring a six-pack of Budweiser, and then Ace wound up bumming all his Budweiser’s off him the whole night … “Hey John, can I get another beer? Hey John, can I get another beer?”

Andrew:

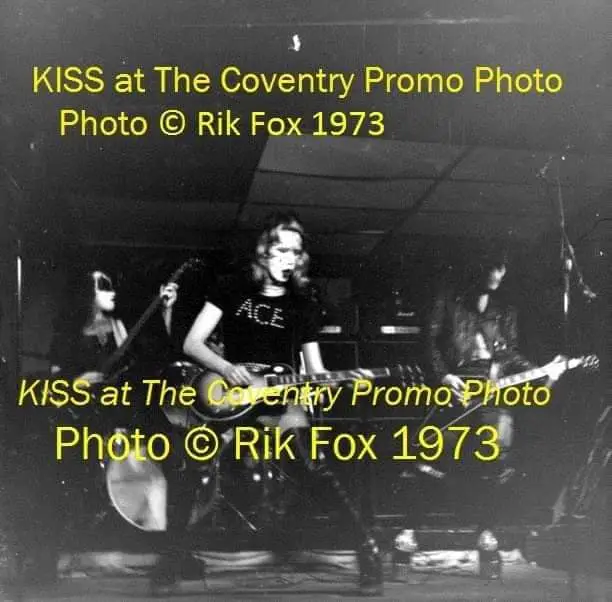

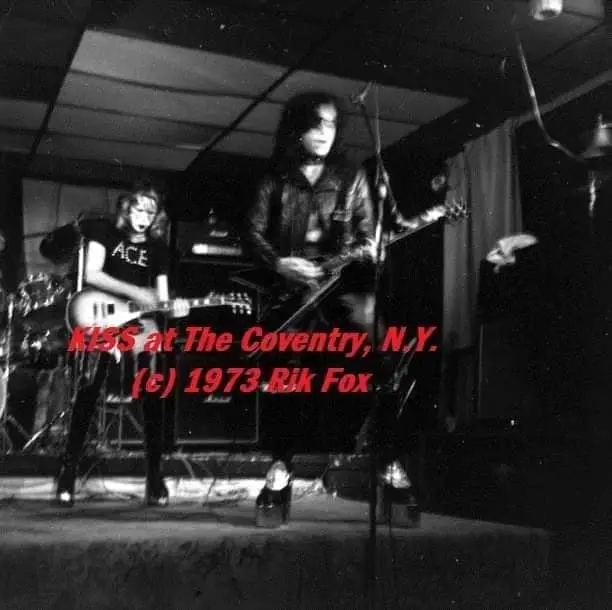

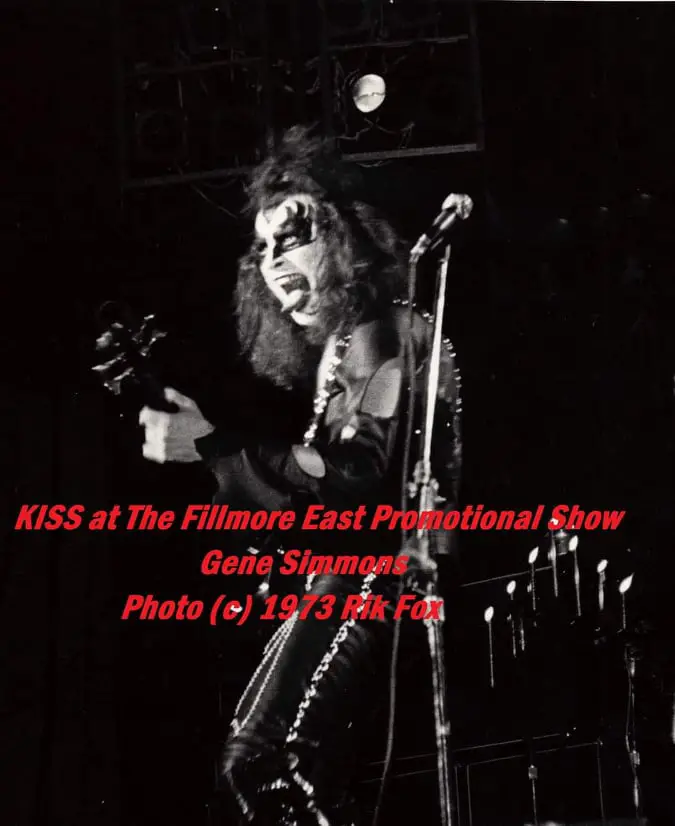

You also photographed KISS in the early days. Do you have any vivid memories of early gigs?

Rik:

We saw them play at the Diplomat show with several of the other up-and-coming hot Rock bands. Bill Aucoin was sitting behind us at the Diplomat show with one of his business associates, and I had bought a bag of balloons, and I’d blow each one of them up, draw the KISS logo on it, and then deflate it. I’d have ‘em in a cigar box, and you can’t have them rub up against each other, because the ink would smear once you deflate the balloons. It wasn’t like professional printing. Once they finally became KISS and had a logo, I would draw, with a magic marker, their KISS logo on all these balloons. We’re in the front row – me, John, Joanne, Donna, our friend Ann Marie, and whatever other friends of ours from Greenpoint that were into them. Bill was gonna leave, and he said, “So, what is it about this band? Why should I stay to see them?” And we just kind of surrounded him, and gave him the whole marketing deal about why he should stay there and see this band. So, they stayed, and the rest is history.

Right when KISS was coming on, I start to hand the balloons out to all our friends in the front row, and they blow ‘em up real careful. So, there are five or six of us sitting in the front row, with armfuls of these balloons with KISS logos that I drew. And the band would come on, they opened up with “Deuce,” and come on with all the power and flash, but they didn’t have any effects though, yet. And we all stood up at the same time and threw all these balloons at them. There’s like, I don’t know, 40-50 balloons, and Gene’s like looking around going, “What the hell? Where did these come from?” And they’re looking at them as they’re playing, and they see it says “KISS” logos on them. Gene does his monster gig, and he’s stomping on them, and Paul’s kicking them around the stage, Ace is kicking them around the stage. Bill Aucoin found all this very interesting. So, as we were able to infiltrate the Aucoin Management circle, we go around to see them at the other shows. I’ve got pictures of them at Coventry, as the money started to come in, they got some new gear, new boots, new clothes. They played at The Sunshine Inn, at Asbury Park, in New Jersey, and I’ve got pictures of them there. Then they did this big promo show at what used to be The Fillmore East, which was like a promo show for Casablanca and Neil Bogart. I got down front — I was one of the only people with a camera who knew exactly when Gene was gonna spit the fire. I’m watching him through my viewfinder — he’d hold up the torch and he’s checking for the direction of which way the wind is blowing — so he could blow it in a safe direction. I’m watching his lips, and I could see when he’s tightening the muscles in his lips, so as soon as I clicked the button, it synced up perfectly when he spit the fire, and I got a great shot of him shooting this huge ball of fire out of his mouth. A lot of people who do the KISS books, and things like that, they love that shot.

Andrew:

Were you in attendance for the first gig?

Rik:

They did some early shows — see in Manhattan — various bands had something called a loft. A loft was nothing more than an industrial space, and they would have loft parties. That was just where they would rehearse, sometimes they lived there. Like I said, big, open industrial area inside. You’d get off the elevator, and there may be an office and there was like this whole open floor space with windows all around. And KISS had played one or two of those with some of the other bands like The Brats, I think the [New York] Dolls were there — I don’t know if the Dolls played at the same time as KISS. I think that was kind of their preliminary, probing-type to feel themselves out in front of some of the crowd.

By the time they did Coventry, they had a couple of dollars thrown in. So, they had newer amps, they had some upgraded costuming. They were still feeling out what their stage show presentation was, and that was being worked up with them by Sean Delaney, who was Bill [Aucoin’s] partner. Sean was like an off-Broadway choreographer, producer, and songwriter, and he’s kind of the fifth member of KISS, if you will. He taught them all of their choreography; he had all of their costuming built with the leather and the studs. It all came from Sean Delaney. When they used to open with that song “Deuce,” and they would do that little back-and-forth body movement — that was coordinated to the music — Sean taught them all of that. I learned all of that from him, and subsequently, he taught it to the band Starz, who were also under Aucoin Management. All of that came from Sean Delaney.

So, I was at those early shows at Coventry, and then, of course, the one of Gene blowing the fire was at the old Fillmore East — which was the press presentation for them being signed to Casablanca.

Andrew:

You eventually left New York for Los Angeles in 1982, which gave you exposure to a different scene, and created new opportunities. How did you manage to line up an audition for Sister, a West Coast-based band?

Rik:

Okay, so we’re back to me working in one of those clothing stores in The Village on 8th street. It always seems to be a default point of where these things start to happen. These seeds get planted. I’m working in there, and again, these guys come walking in, they were vacationing from California, and they said that they came to see some festival that Twisted Sister was playing at. They flew all the way in from Los Angeles. I said, “I know those guys. They’re friends of mine.” They’re like, “Really? You know Twisted Sister, personally?” I said, “Yeah. We played the same clubs. I saw them before Dee Snider was in the band.” I saw the original Twister Sister lineup, and of course, SIN would sometimes rehearse in Manhattan. And one of the rehearsal studios we were at, The Dictators were rehearsing right next door at the next studio over. They heard us playing, and they would come in. Ross [Friedman] would come in, and Mark Mendoza was playing bass with The Dictators at the time. And Mark used to hang out, so we got to be really good friends. He’d hang out with us while we were rehearsing, and he gave me his home number and we’d call each other up and talk once in a while. Mark wound up eventually becoming a roadie for Twisted Sister when Dee got in. And he was in the right place at the right time, so he wound up getting the bass spot. So, he’d tell me, “Come and see me play, come and see me play. Come hang out with me.” Which I would do. I got the Rock Star look, and of course, Dee Snider developed an attitude about that and would get pissed off and try to have me thrown out of whatever venue they were playing at. Then Mark would get into a fight with him and say, “Shut the fuck up. He’s my friend. He’s here as my guest.”

So, anyway, I’m working at this store in the Village, and they were KISS fans, and I said, “Okay, I’m friends with KISS, too.” And I tell them what I told you, about the early beginnings, and telling these guys, this was as if they were meeting somebody from the actual band themselves. These guys were in shock and awe. They said, “Well, we know a band in Los Angeles, where we’re from, and you look like you’d fit in perfectly.” I’m like, “All right, I’m hearing this story again.” And I eventually wind up replacing whoever the bass player was in the other band. My whole career has been replacing people. So, I gave him my neighbor’s phone number in the apartment next-door, because my phone wasn’t turned on, I was living in Jersey City at the time. I had a picture in my bag of me playing on stage with one of the bands that I played with, and I said, “Here. Here’s a phone number and here’s a picture.” I never thought I’d see these guys again. I could never imagine myself uprooting from New York and going to California to try out for a band. I mean, that’s a leap of faith, just to audition and fly across the country. I don’t think I ever asked Blackie how he got the money to fly me out there. He had to borrow it from somebody, ‘cause he was broke at the time.

So, they flew me out to Los Angeles with my bass, my bass head, and just a small amount of clothes. They picked me up from the airport; Mike Solan actually drove. Mike Solan was Blackie’s right-hand man. Mike was Eddie Solan’s brother; Eddie Solan was Ace Frehley’s guitar tech, and an early sound man for KISS, and Mike is the guy who plays the bartender in the W.A.S.P. video, “Blind In Texas.” He’s the cowboy bartender. Mike was really cool; he picked me up from the airport, and we went back to Blackie’s house. Randy [Piper] and Tony [Richards] took my gear to their studio, which was kind of naïve for me, because they could have taken it anywhere or took off with it. It was called Sister at the time; just a lower-cased ‘sister’ with a pentagram on fire. That was their logo. Once the jetlag passed, Blackie took me out to The Troubadour. I met David Lee Roth, which was pretty cool ‘cause I saw them at The Palladium, and I got his towel after the show. Then you figure, “Wow, how cool is that?” Then Blackie takes me up to The Rainbow, and David Lee Roth comes up and sits at our table. I was like, “Somebody pinch me. Is this real or what?” But that’s the kind of club The Rainbow was, it was the home of the stars. All the biggest bands in the world hung out there. Then, before I walked in, Punky Meadows was standing by the front door with Michael Diamond — who was the bass player for Legs Diamond — and they both were like, “Hey!” And Punky said, “What are you doing out here?” I said, “I came out from New York to audition for Blackie Lawless’s band,” and he went, “Oh, okay. Good luck!”

So, we eventually got down to business, and about a day or so later, Mike Solan picks us up and drives us down to Randy Piper’s studio in Anaheim. And I’m sitting there, and they say, “Okay, we’re gonna go through the set a couple of times and then you’ll come up.” And I went, “All right.” As I sat there in the chair, watching and listening to what would eventually become W.A.S.P., I felt like I was taken back to the loft watching KISS; it was like a direct pipeline. Now, I’m seeing a band that’s standing in front of me — I’ve never heard anything like it before, I’ve never seen anything like it before, I’ve never experienced anything this heavy outside of seeing Judas Priest in concert — and then it’s gonna be my turn to get up and play with them. After five songs, they said, “Come on up.” I plugged in and I pretty much caught on — I mean the songs were easy enough — pretty much three-chord stuff. I’d never heard a singer like Blackie before, and it was pretty powerful stuff. We ran through the set a few times; they didn’t make up their mind right then and there. I landed on February 4th of ’82, the first audition was on the 6th, and then, we did it again on the 8th. The night of the 8th was the defining one. I really had the songs super-nailed. I have a melodic style, from my influences, but Blackie’s going, “Can you play it simpler?” I mean, Jesus, these things are three-chords! How much simpler can I play? As you get into the 80s, instead of where the bass player would follow the guitar player, the bass player would now just play like a root, and drone on an eighth note or sixteenth note, and the guitar pattern would pass over it. So, I came from a different background, a different discipline. Now, I’m adapting to what they’re doing in California. By the end of the 8th, Blackie says, “All right, you got the gig.” So, that’s how the audition happened. It was just the result of somebody passing my phone number, and my picture to Blackie.

Years later, I found out more about the politics that were going on in the background. Originally, Blackie had offered the gig to Don Costa, and Donnie didn’t want to play with him. Blackie had a reputation; the people that worked with him would just leave. They didn’t wanna deal with him. He’s very controlling — he’s got a vision, I’ll grant him that — he’s got an idea of how he wants to do what he wants to do. Some of it’s based on what he’s borrowing from other people and tweaking it his own way. Gary Holland played drums with them before I got there, and it got to a point where Gary couldn’t stand playing with Blackie. The “anti-personality,” some people just don’t wanna deal with him. He’s too commanding, I guess. So, Gary left and went to Dante Fox, and Dante Fox’s drummer swapped and ended up playing with Blackie. And that was Tony Richards. Then Dante Fox eventually changed their name to Great White.

So, Donnie turned them down. I didn’t know this until later. So, I got the gig, and I asked Blackie what happened to the other bass player, that was Joey Palermo. He said, at the time, “Don’t tell anybody this, Joey got shot in the back during a drug deal.” And we never heard from him again after that. I don’t know if he was alive, if he died, or whatever. He’s one of the missing puzzle pieces that all the interviewers want to talk to about the early history of W.A.S.P., but nobody can find him. He’s off the map completely. I don’t even know if he’s still alive. But Blackie told me that’s who I was replacing. That was their bass player from Circus Circus, and then he was in Sister.

Andrew:

You mentioned Joey Palermo as a missing puzzle piece, but the same could also be said for Don Costa, who, by all accounts, was a phenomenal bass player who had opportunities with several notable acts before disappearing from the scene altogether. He was known for his over-the-top bit, centered around a cheese grater attached to his bass.

Rik:

I didn’t meet Donnie until after I was out of W.A.S.P. I just remember the piercing blue eyes, the mounds of black curly hair, and the smile. He was a nice guy; he was nice to me. He had the whole cheese grater bit on the back of his bass, and all that. Apparently, after I was out of the band, he stepped in — he finally conceded — and he did a show with them at the Woodstock, down in Orange County, in California. I think maybe he upstaged Blackie or something, because he had the whole cheese grater thing, and girls were licking the blood off his knuckles. Blackie doesn’t like being upstaged, and Donnie got kicked out or he quit. And the other thing I’ve been hearing is that Chris Holmes didn’t get along with Donnie. From what I understand, Donnie was a fantastic bass player. He started out as one of these guys that would be like a master player, but he wouldn’t do anything on stage. He just stood at one spot by his amp and played. Eventually, he was convinced to move around a little bit more, and he just went totally full tilt in the opposite direction, and he was all over the stage. So, he was an excellent bass player, and he had a lot of charisma, and attraction on stage, and star quality — if you wanna call it that. He did the one show with W.A.S.P. and then he was out. Then he went over to Ozzy Osbourne, and I guess he unknowingly upstaged Ozzy during a show, and he got fired from Ozzy.

Andrew:

Few appreciate the sacrifices made when pursuing a lifelong dream. Your particular situation, uprooting and moving to L.A. where you didn’t know anyone, and essentially betting on yourself is unique. Talk about some of the initial challenges you encountered while trying to make ends meet.

Rik:

Well, originally, when I was in New York, I was working for a really large, and prestigious marketing research firm. I became really good friends with the office manager, and I told her I had an opportunity to go, and audition for a band in California. She says, “Oh, well we have a satellite company in Century City. I’ll make some phone calls to see if I can get you an opening, this way at least you’ll be able to have a job.” I said, “Great. That would be perfect.”

So, when I got to California, and after I was settled in with auditioning and being with the band, I went down to Century City and I contacted those people. I said, “I came out from New York. I’m sure you got the message from the office manager from the New York branch.” They said, “Well, we can’t just create an opening for you. We’re like the same company, same name, but we’re a satellite. We’re related and we’re not, so even though you were told that you’d have a job waiting, we can’t just force an opening for you, so you’re gonna have to wait until there’s an opening.”

That really put the kibosh on my opportunity to at least start making some money right away. That, of course, would have raised my value in living at Blackie’s, because he was pretty much living hand-to-mouth; he was starving, too. He was making stage monitors and fog machines for any bands who could afford to commission him to make them. And if I was helping him, now he’d have to split whatever little money he was getting from them and give something to me. I have to say, that was the first time I was ever forced to take food from a market, late at night, and I’m not really proud of that. I had no money, I had nothing to eat; I had to survive somehow. Every once in a while, some of the kids that I met out there would take me out to get a burger or something. That’s not enough.

There was an avocado tree growing in the courtyard outside of Blackie’s rental cottage. I had never eaten avocados before — I wasn’t familiar with them — because in New York, we don’t have avocados! That’s predominantly a West Coast thing. I opened one up and I saw how slimy they were, and I’m like, “People eat this!?” That was my ignorance, not knowing that I had food right there in my hand that had protein, and was nutritious. I was completely ignorant to that fact at the time; there’s literally food falling on the ground from this tree in my hands, and I just threw them away.

Blackie, he got a book by Abby Hoffman, who was one of those revolutionary, hippie people from the 60s. And Abby wrote a book called, Steal This Book — which a lot of people wound up doing and Blackie did also. It tells all these different ways you can live — not off the grid — but how to survive, literally, if you’re starving and whatnot. One of the tips in the book — back then, the utility companies weren’t wise to it yet, but after going to Blackie’s house a couple of times, they caught on — he was able to open up the locking collar on his electric meter. He could screw the glass off, reset the numbers back, and then put the glass back on, put the collar on, and put the little wire-twist thing on it. At a certain time of the month, all the shades on the windows were pulled, the doors locked, and he’d say, “Don’t answer the door.” He had it gauged around the time that they would come and read the meters. And they would come and see that the number hadn’t changed, so it looked like no one was living there. Meanwhile, wherever the meter power goes to, they could see that electricity was used at this location. So, that went on for two, maybe three months, and they caught on and put a more secure lock on the collar. And [Blackie] got pissed off about that, because he couldn’t keep dialing the meter back. That’s how bad it was financially.

The girlfriend that I was going out with back in Jersey, once I came to California, all my gear — my amps, my cabinets, everything was back there — she took all my gear back over to Pastore’s Music in Jersey City and sold it back to them. Whatever money that was leftover, I paid the last part of my rent to my landlord. And she sent me the balance, and I had a couple of dollars in my pocket for however long I could stretch that out. Being with W.A.S.P. for only four months, how long is that money gonna last, you know?

Looking back, in retrospect, I should have reconned my situation better. The first thing I should have done was get a map of the Hollywood area, and study all the streets, routes, where the buses go, how to get to this place and that place. They had these newspapers, like the ‘Pennysaver’ classifieds, and people could sell things or buy things, I should have contacted them and even asked if I could get a job in their office. The first thing I should have done, before I even put any roots down, was try and find some way to find any form of employment, even part-time.

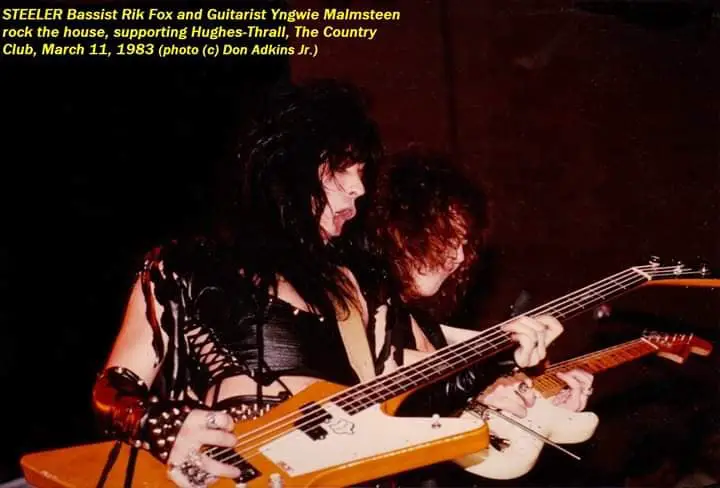

By the time I was in Steeler, I had tried to split my unemployment benefits between what I had from my time working in New York, and what little I did in California. That was a new concept, splitting unemployment benefits between East and West Coast. There was an unemployment office just down the street, actually, from where Blackie’s house was. When I was in Steeler, I would take the bus up into Hollywood, and go there like every week or so from unemployment, and until they could okay everything, and then I got some benefits. So, once I was in Steeler, sometime after I was in the band, that came through, so I had a couple of bucks in my pocket then. Which didn’t really endear me too much to the guys in the band, because everyone was starving. How can one guy have money in his pocket while everyone else was broke? I mean, I had enough money to buy an SVT amp head from a guy for a couple hundred bucks.

It was hand-to-mouth; that’s when you find out what the “couch tour” means. We didn’t have that phrase in New York, but in California, you find people who you can become friends with, and they let you stay at their place for a temporary time, and you sleep on their couch. And you go from one place, to another, to another, to another. And that’s what they called the “couch tour.” It’s nothing to be ashamed of because if you don’t have any resources at your disposal, you gotta try to live by your wits. Of course, a lot of the girls at the clubs, they feel bad for you, so they’d go out and get you groceries or take you out to get something to eat, if they thought you were cute. And that was pretty much how all the musicians survived, unless they had a job.

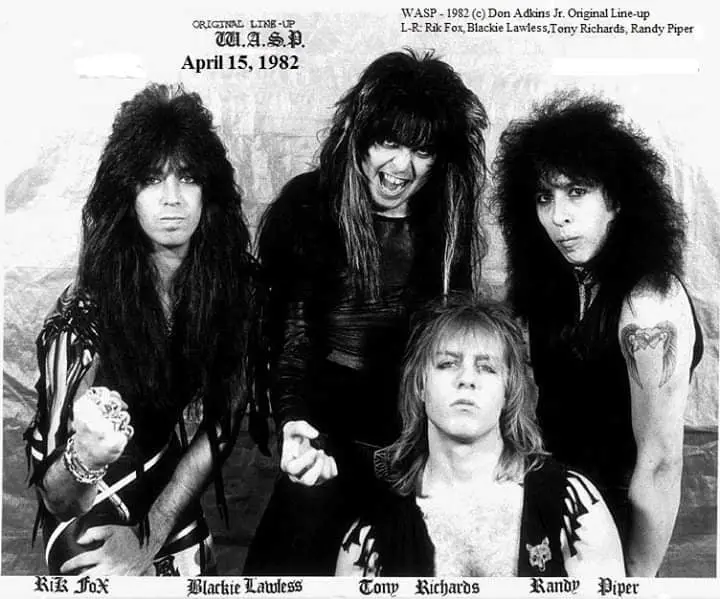

W.A.S.P. photos by Don Atkins, Jr.

Andrew:

Given the perceived cohesiveness within the band at the time, I imagine your dismissal from W.A.S.P felt very left field.

Rik:

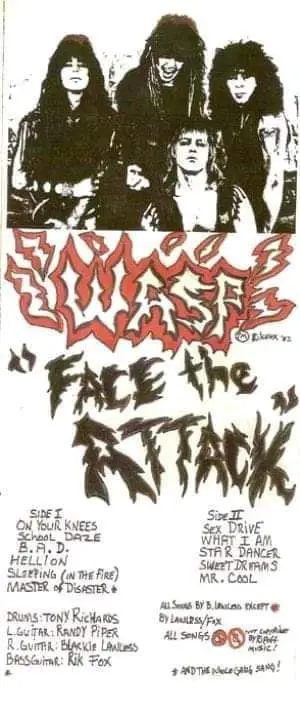

I was in the band for four months; I obviously recorded the first demo with them, and I co-wrote one of the songs. Actually, all the songs, I wrote my own bass lines for, but as far as writing a song-song, I co-wrote with them the song called “Master of Disaster” — which a lot of fans think wound up turning into “Wild Child,” because the similarities are too close.

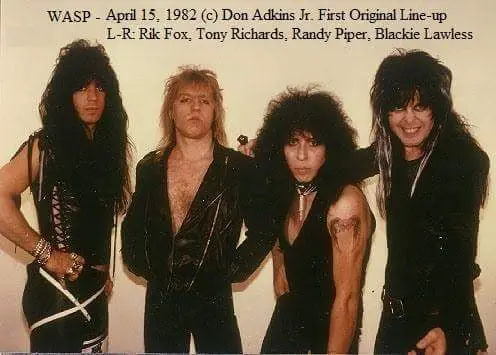

Blackie, obviously, felt happy and comfortable enough when we listened back to the demo, that he called Don Atkins up — who was a photographer — and scheduled a photo session. So, at that point, Blackie was pretty happy with everything. Then at the end of May, he comes to me out of the clear blue and was not talking to me. I’m living at his house, and it’s just cold. He wouldn’t talk to me unless he really had to. Then he sits down and goes, “You know what? It’s not working out. Randy’s not happy. Tony’s not happy.” And I’m thinking, “Well, the demo sounded great. What went wrong?” And he says, “Well, you’re out of the band. You don’t have to leave L.A., but you can’t stay here. And you are to surrender all of your photos.” It’s like, “That seems premeditated.”

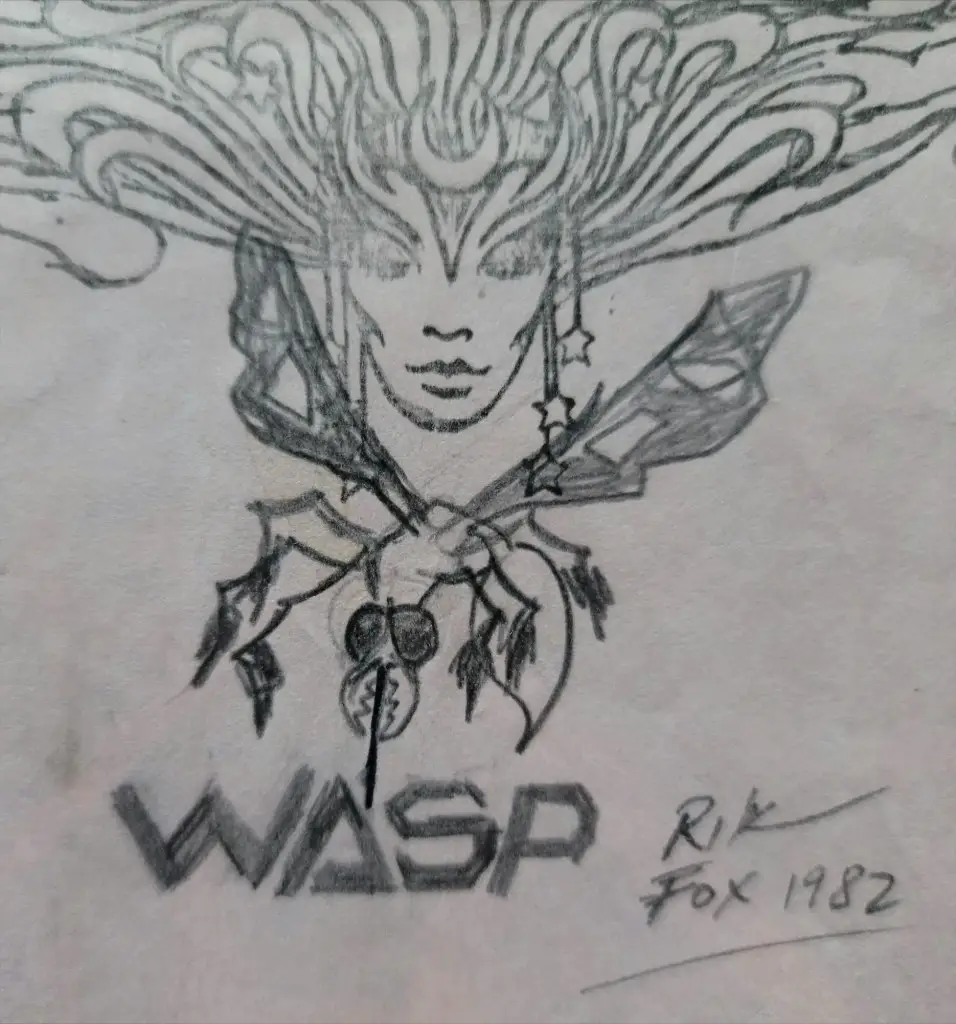

In March, we did the demo, and then came the incident where I stepped on the wasp outside his house, and I came back in and I said, “I got an idea for the band name.” Because he needed a new everything; he didn’t wanna use Sister anymore. He wanted a new name, a new theme, a new concept, everything. Start over. And I said, “What about Wasp? I just stepped on one outside.” So, at that next rehearsal, he got us together and said, “Hey, we got a new name for the band.” And Randy goes, “Well, I wanted to call it Hellion, because that’s what they call bad kids in Texas.” I said, “Well, there’s already is a band in Hollywood called Hellion.” And Tony goes, “Who names a band after a bug?” And I said, “The Beatles…Scorpions.” Blackie goes, “Well, that’s it. The name of the band is Wasp.” So, at that moment, technically speaking, all four of us were the new co-founders of the band, on that technicality. So, that makes me a co-founding member — especially since I came up with the name.

I was out doing my laundry and was looking at a newspaper, and they had a promo shot of Mel Gibson from Road Warrior. You know, the shot of him with the shotgun in the holster, and he’s got the dingo walking next to him as he’s walking down the road; he’s got the leather jacket with the sleeve missing. I’m thinking, “Hey, you know, there was a band from Australia in the 70s called “Heaven,” and they all had that Road Warrior look. Each one had a little bit of different Road Warrior image in the band.” I said, “I think that would be a great concept.” Blackie said, “No, no, no. We’ll scare off the record labels. We gotta get signed on our material first and then we’ll do the image later.” Of course, I’m out of the band…what’s their first image? Road Warrior — fishhooks, leather, saw blades, tools, and a sign on fire. So, you kind of start seeing a pattern here. So, I was out of the band by the end of May, and he tells me to surrender all my photos. I said, “Why?” He said, “’Cause it’s my band and they’re my pictures. I paid for it.” I didn’t sign any waivers; I didn’t sign any disclosures. So, when he left the house, I took the negatives, and I went out, and I had pictures made, and came back. When he found out, he went ballistic. He started yelling at me like I was some kid. Luckily, I stashed a few of the pictures away, because that, and the demo is all I have to prove that I was in the band. He obviously didn’t want to have any credit go to anyone else after I was out of the band.

[Blackie] added the periods in the name W.A.S.P. My original artwork, it was a hornet, like the old Green Hornet logo. That’s kind of what I was drawing upon. I showed him that. Then he added the periods in case I was gonna try to get around him to fight over the name. That’s when Chris Holmes came into the picture because after Donnie left, Blackie moved over to bass and Chris Holmes was officially brought in. To the best of my recollection.

Andrew:

So, your original artwork was similar to that of the old Green Hornet logo?

Rik:

Yeah. If you remember back in the 60s, the Green Hornet TV show, it was a hornet kind of curled and coming at you, and it had an optical pattern behind it, suggesting an aggressive insect coming at you. And that’s kind of what I drew up. The thing is, in some of these fan groups, they are overly zealous to a fault, what’s the word — they’re like neophytes, or sycophants (psycho fans) [laughs]. They’re not W.A.S.P. fans; they’re just strictly Blackie fans. Big difference. And Darren [Upton, author of W.A.S.P. Sting In The Tale] says, “From the first album to Crimson Idol, a lot of the fans believe your side of the story and they’re with you on it,” … “But from Crimson Idol on, those are the fans, for whatever reason — we haven’t been able to put our finger on it — these people detest you. They just out-and-out hate you.” And nobody will ever really say why, but just because Blackie won’t admit it, whatever Blackie says, they go along with it, blindly.

You know, you could be the greatest artist in the world, and reach people’s hearts, and souls with your lyrics, and your arrangements, but if you’re the kind of person that really doesn’t care about the people who spend their money on your material, and who doesn’t want to interact with them at all and play Mr. Mysterious, well it’s gonna have some kind of an adverse effect on some of these people.

It became enough of a contestable issue, that interviewers would start talking to the other members. They mentioned me in an interview with Full In Bloom Music; they talked to Tony Richards. I don’t know what happened between the time I left the band, and the time Tony did the interview, because when I was in W.A.S.P., Tony and I got along like peas and carrots. I mean, as a rhythm section, we were having fun with each other. We’d kind of make fun of Blackie behind his back, and we’d giggle, then he’d turn around and go, “What? What’s going on?” Me and Tony would look up at the ceiling and whistle, like school kids that almost got caught. That’s the kind of camaraderie Tony and I had. Then something snapped in him, and he completely berates me. He has nothing nice to say, so I don’t know what happened to him.

Then they eventually interviewed Randy, which is up on YouTube, and they said, “So, I gotta ask, was Rik Fox in the band? Yes or no.” And he goes, “Well, yeah, Rik was in the band. We rehearsed with him for a while, then I don’t know, I guess it wasn’t working out.” Randy will evade a direct question; people don’t like to get pinned to actually answer a direct question as it’s asked, so they kind of evade it loosely around the edge of the answer. And they said, “Well, did he come up with the name?” And Randy validated it… “Yup, Rik came up with the name. Blackie put the periods in it and stole it from him, I guess,” and he starts laughing. Then he goes, “Yeah, but I can’t take that away from him. Rik did come up with the band name.”

Now, you take these things with the validation from other bands members, from Randy, from Chris; I’m friends with Stet; I’m friends with Johnny Rod. These people say, “Yeah, he was there.” I’ve got some testimonials from various people saying, “Well, I was there at the Sister (eventually, W.A.S.P.) rehearsals. I watched Rik playing with them.” And I post this stuff and Blackie’s fans are shooting it down and going, “Well, where’s your gold records? Where’s your tour?” I mean, this is their response, like my validation is not enough. Being on tour, and having gold records, that’s more validation to them.

Andrew:

It’s a shame that it had to be that way. Maybe I can help you clarify any misconceptions regarding your tenure. How long were you in the band, and what were your contributions?

Rik:

I still have my plane ticket — my original plane ticket — and it was an airline that no longer exists called Capital Airlines. I arrived on February 4th, 1982, in the early evening, and then in March, we did the demo tape, in April we did the photo session, and then I was out of the band by the end of May. So, about four months.

And of course, my contributions being I played on the first demo, and then the photos that exist. And the photographer, Don Atkins, has gone on record in public saying, “Blackie called me up and said he was really happy with the band, and he wanted me to come and do a photo session. So, we brought everybody to my parents’, and we did a photo session at my parents’ house. Rik was definitely in the band. I can’t speak for Blackie’s politics, why he won’t acknowledge Rik was in the band, but Rik was definitely in the band. Rik was starting to become a regular hanging out on the scene.”

Andrew:

You mentioned the demo you played on, about a month into your tenure with W.A.S.P. It’s nearly impossible to find these days, so what can you tell me about that?

Rik:

That all took place at Randy Piper’s rehearsal studio, “Magnum Opus,” in Buena Park. Blackie had gotten hold of a reel-to-reel tape recorder, with the big reels on them. He said this was gonna be a live three-track, which means we were not gonna do any overdubs. It was just, turn it on, hit record, run back to the amp, plugin, and play. And that’s what we did. We did six songs because, by that point, I had already co-written “Master of Disaster” with Blackie with the band.

So, we did “On Your Knees,” “Hellion,” “B.A.D.,” “Sleeping in the Fire,” “School Daze,” and “Master of Disaster.” And we recorded them live, just like that; it was an old, in-the-room, ambient setting like that. We ran through a couple times just to get the settings, and we’d roll it back, and you could start over and hit record. Eventually, those songs wound up on cassette copies. Randy had one; I had one; Tony had one; Blackie had one. Blackie was pretty happy, that’s what he told me, he said he was pretty happy with the outcome.

Sometime after that, about a year or so after I was out of the band, I had like four milk crates filled with record albums that got shipped to California from New York. My dad shipped them out. So, my cassette copy of the master of the W.A.S.P. demo, what I did was, I envisioned what a potential album cover would look like. So, I xeroxed a copy of the band shot, and I drew my own type of font lettering of the W.A.S.P. logo and it said, “Face the Attack.” I made it look like an album cover; I put our names, who we are, what we play, and the song list. I took it to a xerox place, and I reduced it down, and I made my own customized cassette flap for the tape. It looks like something an artsy fan would do.

That cassette tape was in a car at a place I was staying at in North Hollywood. They didn’t have secure parking, we just drove in and parked under the building, and the car was right near the entrance of the parking structure. Well, I was out for a couple of hours, and when I came back, the car was gone. And the girl I was going out with, that was her car. We didn’t find out until later that somebody set it up to have somebody break in and steal the car. Some of the milk crates with my albums, and some of them were bands that I worked for that signed the albums for me when I was doing lighting in New York, those were in the backseat. Anything that was in the trunk, was still in the trunk when we wound up picking up the car from the police impound. But whatever was inside the car itself, like the backseat, was stolen. So, some of my best collector albums were gone, and along with it, that W.A.S.P. demo.

Now, somebody must have known the value of that W.A.S.P. demo because it was from that point on, that W.A.S.P. demo wound up going around the world. And all the W.A.S.P. fans falsely believe that it is an actual, sanctioned W.A.S.P. demo. They refer to it as the “Face the Attack” W.A.S.P. demo. It’s not; “Face the Attack” was something I made up for my own personal self; a fantasized idea of what it would look like for my cassette collection. Subsequently, that W.A.S.P. demo wound up going around the world. And of course, with each generation of it being copied, and copied, and copied, it got progressively worse. Over the years, I wound up getting another cassette copy that somebody gave me, and the quality was like half or less than half of the original. The original was almost album quality. I’ve spent all these years, especially when the internet came in, telling W.A.S.P. fans — and in my interviews — that tape is not official. It does not represent any official W.A.S.P. demo release. It was my own personal copy that got stolen. And I wanted the fans to know that.

Andrew:

When would you say Blackie’s disconnect first surfaced?

Rik:

It seems to me that Blackie’s rabbit hole of what he could get away with in business started once he got hooked up with Rod Smallwood, who was Iron Maiden’s management. I guess that’s when they had their conversations about what he could and couldn’t do, or what he could get away with as far as running the band.

I say that because if you look back retrospectively, as soon as the band got signed, the band members got turned from being band members into hired session guys. They were employees and could be hired or fired at Blackie’s whim. That’s one of the things that really infuriated Chris, looking at the lawyers — at the paperwork — he was reduced to be a hired session guy, not a band member. That’s pretty fucked.

Andrew:

I’ve watched Chris’ Mean Man documentary a few times, and one of my most prominent takeaways was just how genuine, passionate, and innately talented of a person Chris is. He was inexplicably overlooked and deserved a brighter spotlight.

Rik:

Well, if each of those members becomes a cornerstone, and helps build the skyscraper to the top, and then the guy in charge — once he gets to the top — disavows the support that he had to help him get there, I mean, there’s no excuse for that. That’s pretty fucked.

Andrew:

By all accounts, the culture and mindset were vastly different in New York and Los Angeles during that time. Given your experience in both music scenes, what were some of the primary factors that differentiate the two?

Rik:

The New York scene is like a big family. Yes, there was some competition and competitive feelings between the bands, but essentially, we’re all on the same team. One of the differences was the crowds; the fans who would go to the clubs to see the bands, especially the ones who were really close to the bands, everybody would dress up like you were on stage yourself. That showed support, camaraderie, and affiliation with the bands. The Harlots of 42nd Street, The Brats, The Planets, Street Punk, Luger, all these bands, people would show support by kind of dressing like the guys in the band. So, everyone went out and got platform shoes, platform boots — those were really big at the time, people in the crowd wore those as well. We didn’t have that phrase “poser.” There was no such thing as a poser. If you were not in a band, but you still dressed like you were in a band, you were showing support for the whole family of the bands that played the club scene in New York. It was an easy, visual identification to show that you were hip to what was going on with the scene. You were kind of part of it, whether you participated actively or not.

I didn’t hear the term “poser” until well after I was in California. Everybody’s a contender. Everybody’s trying to outdo the next guy. It’s related to a phrase I’d heard, called “crabs in a barrel.” Which is exactly what the LA scene was like. In the New York scene, people would kind of help each other … “we were all in this together” kind of feeling. In California, crabs in a barrel — every crab fisherman knows that once you get a catch of crabs, you can put them in a barrel — you don’t need to put the lid on. They’re never gonna get out of the barrel, because what they do, as the crabs climb over each other, they pull the next guy down and climb up on top of him. The whole pattern repeats over and over again, and that’s kind of what the California scene was like. I don’t know if I’d say vindictive, but you could play a show, and the guys in the audience are stabbing you in the back, calling you derogatory names, making fun of you, and trying to put you down, because you represent competition in the arena, so to speak. Then after the show, these same people are patting you on the back and telling you how great you were.

These are things that Kevin DuBrow warned me about. My first night, when Blackie took me to The Troubadour, I met Kevin DuBrow. I said, “I just got in from New York and I’m gonna try out for Blackie’s band.” Kevin was nothing but wonderful, cautionary, and full of advice. Kevin never curbed his tongue; he shot straight from the hip. He upset people with that, but that’s their problem, not his. He told me, “Watch out for this, watch out for that. It’s dog-eat-dog out here, everybody will climb over each other to get to the next thing.” That’s kind of what I was warned about, and he was absolutely right. That’s what it turned into, because if you happen to be in a position where you’re working your way up and you’re getting better billings, better shows, starting to headline — you can be a nice guy and tell the promotor, “Hey, I’d like this guy on the bill, I’d like this band. Hey, these guys were nice to us, they’re friends, let’s put them on the show with us.” Then because you’re in a senior position, you’re sharing the wealth, so to speak, with the opening bands, and you kind of become friends that way. But there are other bands in the audience that are gonna sit there and mock you, make fun of you, put you down, and essentially just talk crap about you. I didn’t go through that in New York; everybody in New York was pretty cool. The California scene, it’s just very competitive.

And that’s not limited to the music industry. It’s also the film industry, movie stars, things like that. Unless actors work with each other on a film, they become friends. But on the lower, under the top success level, you have all of the competition. Everybody’s out for the same job, and there’s always somebody behind you ready to take that job. And that’s the downside; that’s the dark underbelly of the industry in California.

Andrew:

What was the dynamic like within the band during the four months you were around?

Rik:

Well, Blackie was from New York; I’m from New York. New Yorkers have a very different mindset compared to the rest of the country. In New York, you’re raised on street culture, sarcasm, wiseguy cracks; you insult your friends as a form of affection. When you’re accepted into whatever circle your friends with, you’re able to make cutting comments back and forth at each other without it turning into a fight because that’s your form of acceptance in the gang, so to speak. That concept is not very well understood outside of New York, and you take that to California, which was a completely different mindset. At first, Randy didn’t understand my sense of humor, because I’m real quick with the wits, and snappy comebacks. He’s from Texas, and nothing wrong with Texas, but I guess he didn’t understand that kind of humor, and he offered to quit the band. Then Blackie said, “You better get down there because if he quits the band, you’re fired.” And Blackie has a history of being a bully to his own band members — Randy would admit that because he and Randy used to knock heads all the time — even before I was in the band.

So, I went down to the studio. Randy loves champagne, so I got a couple of bottles of cheap champagne, and just he and I sat in the studio, and we just talked for a couple of hours. By the time it was over, we got along like peas and carrots. Randy was laughing at my jokes, he understood where I was coming from, he thought I was a funny guy all of the sudden. We got along great. So, my recollection is that I got along really well with Randy; I got along really well with Tony. Well, all that’s left is Blackie

Blackie lived in this little rental cottage in Hollywood, and he had a very small book stand with some books in it. And he had books in there about Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, and stuff like that. And I said, “What’s with the Hitler books?” He goes, “Well, there was a thing called The Big Lie,” meaning the bigger the lie, the more outrageous it is, the more people are going to believe it. This is a reoccurring theme, and pattern that Blackie seems to employ. After I was out of the band, there comes the big lie: “Rik was never in the band.” The more outrageous he makes it sound, the less I seemed plausible as far as being in their universe. He doesn’t like having to explain me, because that would invalidate his claim that I was never in the band. Friends of mine would see W.A.S.P. out on the road at various shows, and say they’d go up to Blackie… “Hey, how you doin’? I’m a big fan,” and Blackie’s all amicable and nice. [My friend] goes, “Yeah, I’m a friend of a guy who played with you.” Blackie goes, “Who’s that?” They would say, “Rik Fox.” And they said every, single time, [Blackie’s] face would turn red, he’d get this pissed-off look, turn around, and walk away. So, [Blackie] knows. I am the thorn in his side, I am the skeleton in his closet. And don’t give me any of that, “I’m a Christian now b.s.” That’s smoke and mirrors. If he was a true Christian, then he would say, “You know what? You’re right, I should have admitted this. Yeah, Rik was in the band…” At this point, even if he admitted it, finally, I don’t even know if the fans would believe him. He’s the master of deception.

Andrew:

Is it safe to assume you and Blackie aren’t on speaking terms?

Rik:

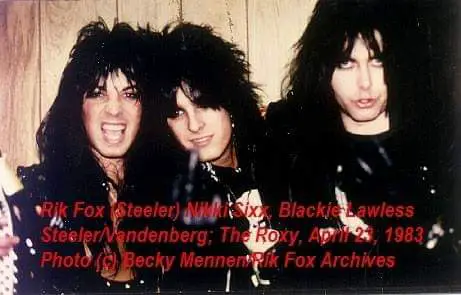

The last time Blackie and I talked, was when I was in Steeler, and we were playing The Roxy with Vandenburg; they had that Top-10 hit “Burning Heart,” at the time. We did a double show; we did an early show and a later show. Between shows, while Vandenburg was on, up in the dressing rooms, Nikki Sixx walks in. I had been friends with Nikki since I first arrived in L.A. — and he had Blackie with him. Nikki pulls me into the bathroom, he locks the door, and he says, “Hey, I wanted to congratulate you. I’ve seen you both try to work your way up, and you’re finally with one of the biggest bands in L.A.” And [Nikki] opens up the little makeup compact and takes out the little white powder and a straw. Here’s Nikki and I bonding in the bathroom, and Blackie’s pounding on the door going, “Hey, what’s going on in there? What’s going on in there?” Nikki giggles and says, “Watch this…Shut up, old man!” Totally mocking Blackie. I mean, they’re friends to this day, but that was what he did at this particular point. We come out of the bathroom, and Blackie, with his big, pouty lips, is going, “What’s going on? What’s going on?” And Nikki’s laughing, and I’m laughing.

I guess Blackie was hedging his bets at that point because I was in a position now — I don’t wanna say a position of power — but Steeler was one of the top drawing Metal bands in L.A. at the time, in ‘83. [Motley] Crüe had already been signed, Ratt was getting big, and there weren’t that many other bands at that level. And we had Yngwie [Malmsteen] in the band, so we were speaking from a position of power. So, Blackie goes, “Hey, if you ever need any help in the business, don’t be afraid to give me a call.” I said, “First of all, I don’t have your number. Second of all, if you really want to be a friend to me, why don’t you just admit to everybody that I was in the band? What’s all this cloak and dagger shit?” And he goes, “Well, the game isn’t played that way.” I said, “What do you mean game? What game? Why can’t you just be honest?” From that point on, he turned on me, and we haven’t spoken since.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of our interview series with Rik Fox.

Interested in learning more about the early demos of W.A.S.P.? Check out the link below:

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vwmusicrocks.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

It’s like people think wasp is this big cash car when everyone’s hands are out. Even if you were in the band so what. What do you want Blackie to do? Yes you were in the band for four months and did cool things. Do you want money or something? Wasp is not a cash cow.