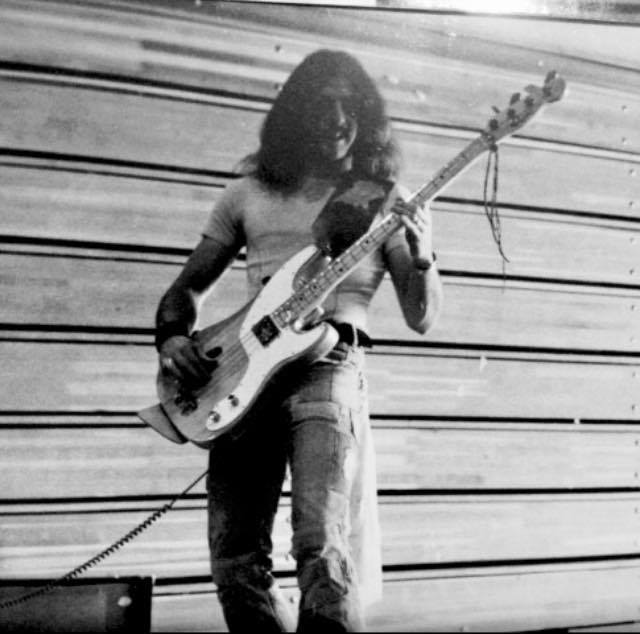

All images courtesy of Greg Chaisson

While most of his contemporaries were working towards their big break in Los Angeles or New York amid a booming music scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Greg Chaisson was toiling in the Phoenix area, honing his chops with various local acts.

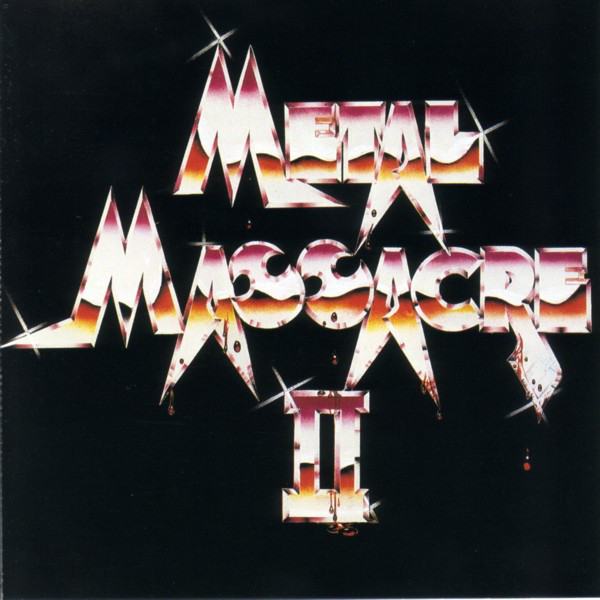

The budding bassist eventually found his footing in the Phoenix heavy metal band, Surgical Steel, in the early 1980s — the band’s demo track, “Rivet Head,” was featured in the Metal Massacre II compilation — before ultimately being jettisoned.

Determined to carve out a career of his own, Chaisson joined the hordes of aspiring musicians in the Los Angeles area at the tail-end of 1982.

In L.A., Chaisson secured coveted auditions with Ratt and Ozzy Osbourne, as well as stints in various bands in between — including the final incarnation of the band, Steeler.

Though Chaisson failed to land the Ozzy gig — it ultimately went to Phil Soussan — he managed to strike up a friendship with revered guitarist, Jake E. Lee, throughout the audition process. When Lee was discarded from Ozzy Osbourne’s band, he eventually presented Chaisson with an opportunity to join Badlands, Lee’s new band rooted in bluesy hard rock.

The initial formation of Badlands featured on the self-titled debut, included a lineup of Lee, Chaisson, singer Ray Gillen, and drummer Eric Singer. The latter was subsequently replaced by Jeff Martin for the band’s follow-up album, Voodoo Highway.

While Badlands proved to be the driving force that ultimately molded Chaisson into a household name, the multi-faceted musician embarked on several successful ventures thereafter, including, but hardly limited to, a solo album entitled It’s About Time with Badlands alum Eric Singer on drums and reuniting with guitarist Jake E. Lee in Lee’s band, Red Dragon Cartel.

Chaisson remains equally engaged these days, managing the Phoenix-based Bizarre Guitar & Drums while also piloting his latest vehicle, Atomic Kings.

I recently caught up with Chaisson to discuss his prolific career in the industry in a lengthy sit-down. Guitarist Ryan McKay, Chaisson’s bandmate in Atomic Kings, also joined in on the conversation to provide insight on the upcoming record.

Andrew:

As a budding musician, who were some of your most prominent influences, and what was your connection with the bass?

Greg:

Well, what happened was, I had just graduated from high school in 1971, and I was supposed to go to college to play baseball. But while I enjoyed playing baseball, my grades probably weren’t going to help me in college and I’m dyslexic, and at the time, they didn’t understand what dyslexia was. So, I had no problem playing baseball, but I just thought the whole college experience wasn’t going to work for me. So, that summer, someone a couple of years younger came up to me and said, “Hey, if you by a bass, you can be in our band.” And I had never even considered being a musician. So, I thought, “Eh, I don’t got anything better to do,” so I went to the pawnshop and bought a $60 bass or whatever it was. It was a piece of junk. And they started to show me parts of songs — none of them knew a whole song — one guy was a drummer, one guy was a singer, and one guy was a guitar player. So, we would just play a verse and a chorus of a song. These guys were at the very beginning stages of their careers, too. I thought that was pretty groovy and I thought, “That’s it. I’m gonna be a bass player.”

As far as influences go, our favorite bands were Grand Funk [Railroad], Mountain, Humble Pie, Free, and Cactus, and bands like that. So, I would try to listen to Grand Funk’s bass player, Mel Schacher, or Felix Pappalardi from Mountain, or Greg Ridley from Humble Pie. Andy Fraser from Free. Tim Bogert from Cactus. So, it wasn’t like I searched out particular musicians to play like or be influenced by, those were just that bands I liked and those were the kinds of songs that we were trying to learn how to play. So, I just kind of naturally gravitated towards the way that those guys played, and they were way, way, way above my pay grade at that point. I always tell the story that I would look at the bass when I was first learning how to play and I’d go, “Damnit, I know there’s a bunch of songs on here somewhere! There’s gotta be some kind of roadmap!”

Andrew:

We know what the music scene in Los Angeles and New York consisted of in the 70s and 80s, but in your early days in the industry, you cut your teeth in Phoenix, AZ. What was that scene like?

Greg:

It wasn’t organized. People weren’t getting record deals from here at that point — I mean Alice Cooper came from here, but he got his record deal in L.A. And he kind of did it by going to Detroit and then going to L.A. and running into Frank Zappa. But as far as in the 70s, people didn’t know major Rock Stars. If any came to town, I certainly wasn’t meeting ‘em. We would just go to concerts and watch them. It kind of changed in the 80s, because Rob Halford moved here, and we would see him out and about, and ended up developing a friendship with him. He was like the first major Rock Star that I ever actually knew here in Phoenix, and he was very approachable. You didn’t get the sense that he was the Metal God or anything like that. He just seemed like a normal dude, and it kind of gave ya hope. And he liked the band I was in; the band was called Surgical Steel. Jeff Martin, Badlands’ drummer, was the singer in it. [Rob] took a liking to us and decided to help the band with what we were trying to do. In the interim, I managed to get kicked out of the band, and I moved to L.A. in October of ’82. So, [Surgical Steel] was still a big deal here in Phoenix, and they had about another year of shelf life. But by then, I was in L.A. and pretty entrenched in what I was doing there.

Andrew:

I understand it was you who came up with the band name Surgical Steel. What was the inspiration behind the name?

Greg:

Well, supposedly, surgical steel is the hardest form of steel, and they use it for medical instruments and stuff. So, at the time, we wanted it. It sounded like a very Metal name, and we wanted something that kind of gave you the image of a real Heavy Metal sort of name, and that’s really how it came about. And people liked it. I wasn’t sure whether people were going to gravitate to it, but it made a great logo and it made a great image. They had to buy it off me after they kicked me out of the band. They had to give me five thousand dollars. [Laughs]. That was a great day when they gave me that five thousand dollars!

Andrew:

How did you become affiliated with Surgical Steel?

Greg:

The guitar player, Jim Keeler and I had been friends. I had tried to start an earlier version of that band, and it didn’t happen. Then Keeler kind of went off and joined another band, and asked if he could use the name Surgical Steel, and I said, “Sure.” They were kind of trying to write their own songs, and they were playing a lot of covers. I knew a couple of guys in the bands; I knew the drummer, Bob. I had recruited him for my first version of Surgical Steel. They were opening for Uriah Heep, and they got booed off the stage, and people were throwing stuff at them. Things didn’t go well. I was at that particular show, and I wrote, and those guys were just kind of figuring out how to write, so they came to me and said, “Hey, we want you to join our band. We’ll get rid of our bass player and we’d like you to join it because we want you to write us some songs.” And I said, “I’ll do it, but if I do it, I have complete control over what we do.” Because I had kind of a vision for what I wanted to do, and they were kind of just all over the road. So, they agreed to it, and we started writing songs. One of the first songs that Keeler and I ever wrote was “Rivet Head,” and we had a bunch of other really good songs that we liked. We were kind of a cross between vintage [Judas] Priest — along the lines of British Steel or Stained Class — and early Iron Maiden.

Andrew:

Metal Blade Records released Metal Massacre II in 1982, which included Armored Saint, Trauma — which included future Metallica bassist Cliff Burton — and of course, your band, Surgical Steel. Were the demos recorded in one studio?

Greg:

No. Everyone recorded wherever they were at, and we sent a copy of that to Brian Slagel. Lo and behold, he liked it. That was kind of my plan: I knew that they had made a Metal Massacre I, and they were making a second one. We knew a couple of guys in L.A. at the time, a guy named Steve Brownlee, and he knew Brian Slagel. He said, “I will hand-deliver a cassette of “Rivet Head” to Brian Slagel, and see what he says.” There were three songs on the demo tape, and he liked “Rivet Head.” It’s a little tongue-in-cheek and it’s kind of silly, but it’s a powerful song.

Andrew:

How challenging was it to adapt to the L.A. scene, which was presumably a vast contrast from what was going on in Phoenix?

Greg:

Yeah, it was weird because I had left Arizona. After all, they kicked me out of the band. I said, “Oh yeah? I’ll show you guys! I’ll go to L.A. and I’ll make it big!” Then I just up and moved to L.A. and I knew three people — actually four because I knew the drummer for this band, Sarge, Bobby Marks. So, I moved to L.A. knowing four people, two of them — Bryan Jay who ended up becoming a guitarist in Keel, and Glenn Mancaruso, who is a drummer friend of mine who played in quite a few bands — we all decided to be roommates. So, we got an apartment, my girlfriend moved out — who is now my wife — and I kind of started going and checking out bands, and seeing what was what, who could play, and who couldn’t.

It was an interesting time because very important times in your life are you at the epicenter of where everything is happening and L.A., certainly in the early 80s, up until ’86, ’87, ’88, was the place to be. It was pretty interesting, my wife and I would go out every night and see bands that were signed playing at The Troubadour on a Wednesday night. Rough Cutt’s playing over here, or Great White’s playing over here. So, we would go see all the different bands — I saw Steeler with Rik Fox in it, with Yngwie. I would go out and see where my skill set landed me. It was very interesting and very informative. It was kind of a character builder.

Andrew:

Upon arriving in Los Angeles, you were one of several bassists linked to Ratt before Out of the Cellar broke. What are your memories from the audition?

Greg:

Yeah, I auditioned for Ratt. Juan had been in the band, and he kind of quit to join Dokken. This is right when the Ratt EP was coming out, and Dokken had made a record in Europe. I think Juan played on it and so did Bobby Blotzer. So, Juan was staying kind of with Dokken; he quit Ratt but he said, “If you guys get a record deal, maybe I’ll come back.” Well, Ratt was still doing shows and they had auditioned about 25 bass players. Aforementioned Bobby Marks, the drummer that I knew, he had come to Phoenix, and Surgical Steel opened for the band he was in and he and I developed a friendship, he called me one day and said, “Hey, here’s Robbin Crosby’s number. Ratt is looking for a bass player and they can’t find anyone they like. You should call ‘em.” So, I called up Robbin about 20 times, and finally, he returned my call, and he invited me over to his house in Manhattan Beach. I just brought my bass and we sat around, and I played. We got along really good and he liked the way I played. So, he arranged for me to go an audition for them. Lo and behold, I end up getting the gig, but the caveat was if they knew they were gonna get a deal. And if they’d gotten a deal and Juan decided to come back, then I would be out.

So, I rehearsed with them for, I don’t know, maybe half a dozen times. They didn’t have their own rehearsal space, so they would have to book a place. They were being managed by Marshall Berle at the time. When they got their funds together, they would call and say, “Hey, we’re rehearsing over here on Saturday or whatever.” They had some shows they were gonna do and they were still writing the first Ratt record. They were writing “Round and Round.” One of the songs that I auditioned was, while they were writing “Round and Round,” they said, “What would you play here?” So, I kind of just played what I would play. Blotzer and I kind of hit it off; Robbin and I already were good friends. And I got along with good with Stephen and Warren as well. But I got pneumonia, so I was really sick for about two months. Well, in the interim, they had a couple of shows, so they had to get another bass player, a guy named Joey [Christofanilli]. Really good bass player and a nice guy. Then when they got their deal with Atlantic, Juan came back and Joey ended up getting fired. So, on one hand, I’d have been pretty pissed off — especially when their first record sold $3 million copies, and I wasn’t in the band anymore — but it was a cool experience. I’m still friends with Bobby to this day. And Warren and Stephen. And I was really good friends with Robbin from the time I met him in ’82 until he passed away.

They would get pissed off at Juan all the time because Juan kind of tended to steal the show on stage — he had a bunch of unique, “Juan-specific” moves. So, they would get mad, and I would get a phone call from Bobby or Robbin saying, “Hey, we heard that Juan might be joining Ozzy. How quick can you learn our material?” And they’re on tour, so I’d hurry up and learn their material and then I’d get a phone call back saying, “Okay, he’s not gonna join Ozzy. Thanks.” And then I’d get a phone call from Bobby saying, “Hey, I’m sick of Juan. I’m tired of all his stuff. Can you learn all the songs? We’re gonna fire him. And can you be ready in like two weeks?” … “Okay, no problem.” So, I learn all the songs again … “Okay, we sorted it out. Everything’s cool now.” So, I probably learned their whole set at least three or four times.

Andrew:

Earlier you mentioned seeing the original Steeler lineup during your introduction to Los Angeles. Shortly after, you end up joining what became the final Steeler lineup. What led to the opportunity?

Greg:

I had joined a band called Legs Diamond, and they’re a band that had some records in the 70s, and they were like Led Zeppelin in Texas. So, they had tours booked in Texas, so I went and auditioned and got the gig and did a tour of Texas with them. But they weren’t playing in L.A. I wanted to play in L.A.; I lived in L.A. I was going to The Country Club every other week, and I was going to The Troubadour, and I was going to Perkins Palace, seeing all these L.A. bands, and I wanted to be a part of that. So, Bobby Marks called me and said, “Hey, we’re auditioning guitar players, do you want to come down and help us audition?” And when I said, “Yeah, I don’t really want to be in Steeler,” I didn’t really get Ron’s voice and Steeler wasn’t doing it for me, he said, “Well, you don’t have to be in the band. We’ll pay you to come and audition guitar players.” So, I went down there, and I helped them audition guitar players, and I picked one that he liked. After the audition, [Ron] took me to dinner and said, “I really want you to be in Steeler.” And I said, “Well, that’s cool,” and during the time that we were auditioning, I kind of saw the method to what I considered Ron’s madness. He had an incredible work ethic; he didn’t mess around. He was very serious about what he did, and it was done very professionally. Ron was very dedicated to what he did, so I was kind of interested. I told him, “Look man, I don’t really play like any bass players around here. I’m straight out of the 70s. I’m very melodic, and I’m gonna play whatever I play. If you can deal with that, I’ll do it, but you gotta pay be $150 bucks a gig.” So, that’s how I ended up in the band.

The first show I did with Steeler was at The Country Club. We headlined and it was sold out. And so, my first show in L.A. — and I was still pissed off that I wasn’t in Surgical Steel, and they’re playing at a desert party somewhere for nothing — and I’m playing at one of the best clubs in L.A. and it’s sold out; 30,000 people or whatever it is. I’m going, “This doesn’t suck. This is actually pretty cool.”

Andrew:

You auditioned for Ozzy in the late 80s, for the gig that ultimately went to Phil Soussan. What are your memories from the audition and initial meeting with Jake?

Greg:

I had already seen Jake play. I’d seen him play in Rough Cutt. My roommates were telling me that the best guitar player in L.A. is this guy Jake Williams. So, I saw him play in Rough Cutt, and I really liked the way he played, and I thought that he was probably the best guitar player I had ever seen; a combination of licks, stage presence, tone, just everything. I was very impressed with him. One of the reasons I agreed to audition for Ozzy was because Jake was in Ozzy, and I thought, “I’d really like to meet this guy, and jam with him, and maybe someday in the future, we could be in a band together.” Total pipe dream, I guess. So, when Sharon [Osbourne] called me and asked me to come and audition for Ozzy, I thought the audition was in L.A., but they were in Inverness, Scotland. So, they flew me to England and then flew me up to Scotland. Ozzy didn’t show up for about a week; he and Sharon had gotten into some fight, and she hit him in the face with a frying pan. We were just kind of up at this Scottish manor up in Inverness. Jake’s a night owl, so he would sleep all day and then get up late in the afternoon, and then me, him, and Randy Castillo would just go in the studio and jam. Just whatever riffs Jake came up with, or I came up with. Jake’s really into jamming, so we kind of developed a friendship based on the way his musical acumen is similar to mine — I’m really into jamming. Even in Atomic Kings, Ryan [McKay], and I do a lot of jamming, just working on different riffs that maybe don’t even turn into anything. So, it’s a big part of what I enjoy. That was kind of the first bonding part of Jake and I’s friendship. Then we had a lot of other similarities. I always say that we’re like opposite sides of the same coin; everything he is, I’m not, and vice versa. And we’ve been friends for almost 40 years, and we’re still friends now.

The reason I wanted the Ozzy gig was, yeah, it would be Ozzy, and I would be on a big tour, and all that crap, but Ozzy is notorious for being shitty to his bass players. And I was thinking, “Boy, I don’t know if I have the temperament to have some guy–” because he yelled at me one night — he was drunk, and he started giving me a hard time about my bass tone. And I was actually fiddling with my amp and Jake was kind of facing his Marshall, and he was looking at me, and I was kind of glancing over at him, and he was shaking his head no like, “Don’t kill him.” I was thinking, “I could knock Ozzy out right here, but how am I gonna get back from Inverness back to London?” ‘Cause I had a plane ticket from London back to the States, but I didn’t have one from Inverness. At the time, I didn’t have any money, so I couldn’t call up anyone and say, “Quick, send me $500. I need a plane ticket from Inverness, Scotland down to London.” I’d have been screwed, so I had to take a lot of Ozzy’s abuse. He didn’t find me particularly funny; he didn’t even want me to audition. When he first met me, he didn’t think I had the right look for MTV, and I probably didn’t. He wanted to send me home without even auditioning me. Jake said, “We just spent a bunch of money shipping him over here. He’s the best bass player that’s been here, give him a listen.” Ozzy said, “Fine. Let him play one song, and then go home!” I was like, “Hey dude, you know I’m standing right here, right?” So, I ended up staying for 21 days and whenever Ozzy got Phil Soussan to be the bass player — and part of it was on the strength of “Shot in the Dark” — but when Phil would piss Ozzy off, Jake would tell me that Ozzy would always say, “We should have kept the ugly guy!”

From that, Jake and I maintained a friendship. I didn’t get the gig, obviously, but [Jake’s] actually the one that called me, and said I wasn’t getting it, but I knew I wasn’t anyway. He would call me from the road, and when he’d be in town in L.A., he would call me up, and he would come over for dinner at my house sometimes or we’d go out to dinner. He had a couple of hot rods, so I’d go over to his house, and we’d tinker on them. We would have been friends whether we were musicians or not.

Andrew:

What were the early conversations like between you, and Jake about Badlands? How did you become affiliated, and did you audition?

Greg:

Well, Jake and I were always friends, and when he was going to start the band, he said, “Hey, I’d like you to come down and audition.” Well, when I first met him in England, he said, “Someday I’m gonna start my own band, and I’d like you to be part of it.” So, I took that as being, “I wouldn’t have to audition,” so all of a sudden I found out I’d have to audition. He didn’t really audition any drummers. He didn’t really audition Ray [Gillen], they just got together, and it all worked. But I was gonna have to audition, and I was like, “Man, if I don’t get this gig, I’m gonna look like an idiot.” All my friends know [Jake], and I are friends, and if I don’t get the gig, I’m gonna look like a real boob. So, I just told him, “I’ll tell ya what…Audition everyone you wanna audition, and if you don’t find anyone, I’ll come and audition.” So, after they had auditioned about 40 guys, [Jake] called me and said, “Are you gonna come down and audition or not?” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll come down.” I mean, I wanted to be in the band really bad. I figured if I didn’t get the gig, it would be better to not even go for it if I’m not gonna get it. So, that way I wouldn’t have to explain to everyone, “I thought you and Jake were these great friends, blah blah blah.” So, I kind of was trying to figure out how to navigate that. When I went down and auditioned, he loved it. I ended up auditioning three times, and then finally I got the gig.

Andrew:

Who were some of the bassists you were vying against? I imagine it was a highly sought-after gig.

Greg:

Man, like everybody and their brother, auditioned for this gig. Some guys were actually in bands that had record deals that had come down and auditioned. If I’m not mistaken, I believe Rik [Fox] might have auditioned. I know my brother Kenny auditioned while he was in Keel. It was kind of considered to be “The Gig,” but I think in hindsight, Jake always wanted me to have the gig. We had spent a lot of time jamming in Scotland, plus we had hung out and knew that we were of the same mindset. I think one of the reasons he had me audition was, if I auditioned, it wouldn’t be like he just gave his friend Greg the gig. He saw other bass players, and Greg was the best guy for the gig. I didn’t see that at the time, and knowing Jake as well as I do, I think that was his mindset. And it was the right mindset because no one could say, “Well, you just got the gig because you were Jake’s buddy.” Well, Jake auditioned 40 other people, too, and some of the guys that he auditioned were people that he was friends with.

Andrew:

Jake, Eric Singer, and Ray Gillen put together a rehearsal tape in the band’s infancy. What was your initial reaction when it was played for you?

Greg:

I thought it was great. We were going to B.C. Rich because they were trying to woo Jake into being an artist for them; I already was. So, they sent a limo to pick up Jake and me, and Jake said, “You wanna hear this tape that I made with the three of us?” And I said, “Sure.” I was listening to Ray, and he was going, “What do you think of this singer?” And I said, “Yeah, the singer is freakin’ off the charts.” I said, “But the drummer — I don’t know who the drummer is — but this drummer is really good, too.” He said, “Yeah, that’s what I was thinking.” I said, “You should get ‘em both.” He said, “Yeah, that’s what I think I’m gonna do.” So, it just so happened that [drummer] Eric [Singer] and Ray had been friends; they’d been in Sabbath together. It’s kind of cool because they came in as friends, and Jake, and I came in together as friends, more or less. Everyone kind of knew each other in a way. Kind of like six degrees of separation.

Andrew:

This is going to test your memory a bit, but do you recall your first gig as Badlands?

Greg:

Yeah, our first show was in Tokyo. It was pre-Cowboy hat for me. There had never been any discussion of what they wanted from me on stage, so I had gone out there and jumped all around like a chicken with his head cut off…ran over here, ran over there. I did that for about three gigs, and Jake came to me after like three gigs and said, “What are you doing?” I said, “What?” He said, “What’s all this jumping around, and running around, and spinning all over? What the hell is that?” I said, “Well, that’s what I thought you wanted.” He said, “I don’t want any of that. I want you to just be you.” As a matter of fact, I was in Japan, and I had a Cowboy hat with me because I always wore one, and he goes, “Wear the cowboy hat and the cowboy boots on stage. It fits your image and fits our name. And calm down!” And I went, “Thank God! Because I’m tired after these shows. I’m tired of running all around. I’m more than happy just to stand over there by my bass amp and play.” And he goes, “Well, that’s what I want, too.” I said, “Good, ‘cause I’m gassed!”

Andrew:

Paul O’Neill produced the first Badlands record. What was your experience working with him?

Greg:

I didn’t like Paul O’Neill, and neither did Jake or Eric. The only reason Paul O’Neill got involved is that he had worked at Leber-Krebs, and at one time, Ray had been signed to Leber-Krebs. He was kind of a gofer at Leber-Krebs. I think he had told Leber-Krebs that, “I think I can sign Ray Gillen’s new band. If I do, can I manage them?” And I think that’s how that happened. I don’t know that for a fact. I never liked him; I never liked what he did; I never liked what he did with the songs. I know he got his name on a bunch of songs, I don’t know how much he wrote. He may have written a sentence here or a word there. But we never had a good relationship. He never had a good relationship with the other three of us in the band. Ray didn’t even care for him that much. I think Ray just looked at him as a necessary evil. He did get us a record deal, which he said he would do. He did get us on the cover of magazines, which we would have gotten anyway. But the one thing that was the issue was — among all the issues with Paul — I didn’t think he was a particularly good producer. I didn’t enjoy being in the studio with him, ‘cause he wanted to take multiple takes of songs, and then splice ‘em together, and we wouldn’t do it. It just wasn’t a good fit.

He was part of the record company. The way that the label was set up, it was kind of a custom label. Titanium was supposed to be “the Badlands label.” We supposedly owned it. Well, you can’t have your manager be part of your record label ‘cause your manager is supposed to fight with the record label for you to make sure you get your fair share and get your say. Make it to your advantage. Paul O’Neill was the record company, along with a couple of other guys. If we were bitchin’ about something, he would do what was best for his wallet — not what’s best for ours — ‘cause there certainly wasn’t any money in our wallets. From the word go, it was a bad decision. I always say, “If you’re gonna get a record deal, make sure your manager isn’t part of the record company,” that’s all I can say. There’s a myriad of reasons why we fired him, and that was part of it.

Andrew:

Describe the creative process amongst the group.

Greg:

Jake would come up with a riff. He would bring it in — it might be a riff and a verse — and he would play them, and we would all start jamming along with it, and everyone would throw in some ideas, and we would record it that night. Jake would take it home, and he would decide which ideas make sense, and which ideas didn’t. Ninety-plus percent of the material is written by Jake; it’s pretty much arranged by him with some input from us. Ninety-five percent of the lyrics and melody lines are written by Ray on those first two records. We all had some input in it, but I mean for me, I write, but I didn’t care about writing in Badlands that much. I like throwing in my two cents worth, or five cents worth, or twenty-five cents worth now and then, but I liked the way Jake wrote. I still do.

Jake has a very unique take on how he arranges his songs, structures his songs, approaches his songs. One of the things that worked as part of our friendship was I’m the same way. The way he writes, I’ve always kind of written that same way. It’s the way Ryan [McKay], and I write together. We don’t try to write a verse and a chorus saying, “Okay, let’s do a guitar solo over the chorus.” We’re always looking for more advantageous, different avenues we can go down while maintaining the integrity of the song, but while making the song interesting to who might be listening to it. Badlands had the same thing. At the time, it was the hair band era, and Badlands — while we all had long hair — we really didn’t fit into that “hair band” era, L.A. strip sort of thing. I actually read in a book one time that we were considered the “worst Hair Metal band in L.A.,” and I was never so happy to be the worst at anything in my entire life.

Andrew:

The first Badlands record was recorded at One on One Studios and the Record Plant. What was the reasoning behind utilizing multiple locations, and how was the workload divided between the studios?

Greg:

One on One, we recorded all the demos we had; we had written maybe 25 songs. Then Atlantic, Jason Flom, the genius that he is, decided that he didn’t hear a hit single. So, he pulled us out of One on One and sent Jake, and Ray to New York to write. They actually had another bass player and drummer there, and I never did find out who it was, and I don’t care anyway. The bass player and drummer just kind of played whatever Jake and probably Ray, and maybe even Paul O’Neill had in mind. When they had the songs they wanted, which would have been “High Wire,” “Dreams in the Dark,” and maybe even “Winter’s Call” — I don’t remember — but when those songs were written, they flew Eric, and I over, and then we recorded just the newer songs. I think we might have recorded eight songs, and we kept the best that we liked from One of One, which would have been “Dancing on the Edge,” “Rumblin’ Train,” “Hard Driver,” “Devil’s Stomp.” And then the newer stuff that was written… “Jade’s Song,” and that sort of stuff from the Record Plant in L.A. That’s how we made the record.

Andrew:

You and Eric Singer didn’t exactly mesh, yet the rhythm section remained remarkably tight on the first album. What incited the fractured relationship, and how did you manage to maintain such a tight-knit unit despite the tension?

Greg:

Well, Eric never wanted me in the band, and he wasn’t too shy about his dislike of me being in the band. Eric’s kind of stubborn that way. When we would rehearse, Eric wouldn’t pay any attention to me; he would just play to Jake. I never actually played with a drummer that did that, so what happened is, he would just ignore me and play to Jake — which is what he does with every bass player — it wasn’t anything personal, it’s just that he doesn’t pay much attention to anybody but the guitar player. So, I started tailor-making my parts. Once Eric started developing the parts that were gonna stay the same, I developed my bass parts based on what Eric was doing. I had been used to playing with Jeff Martin when I lived in Arizona — Jeff is one of the most all over the place drummers that you can play with — so Eric was actually not that hard for me to play with, I just had to figure out how his mindset worked, and fit myself in with it. Then live, as we got going, we would change stuff around a little bit. Well, by then, I kind of knew what Eric’s repertoire of chops was, and when he would start something different, I knew what it would be, and I would change my part on the fly to fit in with it.

I thought we were a great rhythm section. We ended up becoming friends in the last six weeks or so of the tour. Then we were friends for quite a long time; he was a very good friend of mine. When I would go to L.A. after Badlands to do records, I would stay at his house. We were great friends. Then when Rock Candy put out the reissues of the first two records, they put a big, 16-page booklet together. And in that 16-page booklet, I interviewed under the guise that everyone would do an interview. Well, I found out the only guy stupid enough to do an interview was me. Then they put a lot of quotes “from me” that I didn’t say; there was some derogatory stuff against Eric, there was even a derogatory statement made about Jake that I supposedly made. So, when I read these booklets, which I was supposed to have approval over, I told the guy, “Look, you’re gonna cost me my friendship with Eric.” And I’ve never talked to Eric since. I tried to call him and say, “Hey, look, I didn’t say any of this crap.” And he wouldn’t talk to me, and that’s fine. But I did call Jake and say, “Hey, look, I didn’t say this.” And Jake knows me and he said, “Yeah, I know. That’s just a bunch of bull. Don’t even worry about it.”

So, I have never spoken to Eric again. I tried to speak to him for the first couple of years. I don’t wish him any ill-will; he’s a famous Rock Star, I run a guitar store. He’s worth $20 million and I’m worth $25. [Laughs]. It’s all good. As bad as bandmates as we were at first, we ended up becoming that good of friends for quite a few years, probably over 10-11 years. When we fired Eric from Badlands, I voted that we keep him, which surprised Jake, and Ray because they knew how bad our relationship was. I mean, I used to be a flip of the coin every week; beat up Eric, and get kicked out of the band or put up with Eric’s crap. So, I managed to put up with his crap. He’s a great musician, and I totally respect what it is he does. Great drummer, great feel, really funny guy. I was glad that we never got into it because I enjoyed the friendship I had with him, but that was then, and this is now.

Andrew:

The second album included a changing of the guard behind the drum kit. What prompted the switch from Eric to Jeff Martin?

Greg:

Eric, at that point, was not seeing eye to eye with the other three of us. Throughout a 10-month tour, it kind of came to a head, where even Ray said, “This is not going to be workable going into the future.” We had a conference call while Ray was still in New York, and we voted. They voted to fire him, and I voted to keep him. It’s like The Who; would you rather see The Who with Keith Moon or Kenney Jones? Or would you rather see Jeff Beck with Rod Stewart or with Bob Tench? So, I always thought the initial unit of whatever band it was was always stronger. So, having said that, Jeff was the right guy. I brought Jeff in for the audition. He’s a great drummer; he plays differently than Eric. He’s like a roller-coaster going down some crazy tracks, but only one wheel is on the track. For me, that’s easy to play with; I’ve been playing with him since the 70s. He was so different from anyone else in L.A. that it actually worked pretty well. And we were great friends. We still are.

Andrew:

What was it like working with Ray Gillen?

Greg:

Ray’s the best singer I ever heard. It’s very seldom that you’re in a band — I mean, when I was in that band, we’d be on stage and I would go, “I’m in the best band in the world right now.” Jake was my favorite guitar player; still is. Eric was a great drummer — so was Jeff — and Ray was the best singer of his generation. One thing about Ray is that he sang every take of every soundcheck, every practice, every time in the studio, every rehearsal. He never sat around with a piece of paper writing lyrics; he was singing always. And I appreciated that.

A good example would be Dusk, the third Badlands album, which was a demo that we never knew was gonna become a record. But Ray decided to sing, as he always did, every take in the studio — even though we didn’t have lyrics for half of the songs. He was just kind of syllabizing and piecing parts together, and it ends up being my favorite record of the three just because it’s so live. That was Ray. Ray could make you feel like he was your best friend, even if he didn’t like you. We got along great sometimes, and sometimes not so much. But isn’t that how bands are?

Andrew:

While you didn’t have a hand in the songwriting department in the first album, you were credited with a pair of songwriting notations on Voodoo Highway on “Shine On” and “Heaven’s Train,” along with Jake and Ray. What is your recollection of the collaborative process?

Greg:

Well, “Heaven’s Train,” I submitted the riff and part of the song to Jake. I said, “I got this, what do ya think?” We were looking for up-tempo songs and I said, “Here’s what I have. Are you down with this?” And he took it home, rearranged it, and made it a song.

“Shine On,” I forget which part I actually wrote. While he was putting the song together, [Jake] said, “I wanna take this part that you have and put it in this song.” So, it wasn’t like him, and I sat down and wrote a song together. It was more like I gave him a song. And as a matter of fact, “The River,” off of Dusk, was something that I submitted almost the whole song to him, and it never made the second record. Ray was interested in it.

Even with Ray, we collaborated some, but for the most part, he’ll come in with his verse and parts, and then I’ll add to it, or vice versa. It was never that way with Jake; I would kind of just give him what I had or play a riff in rehearsal. If he found something that he liked on it, then we would expand on it. I didn’t really submit anything for the first Badlands record. As I said, Jake had plenty of ideas; I liked the way he wrote. He told me, for Voodoo Highway, “I want you to submit some stuff.” I went, “Okay,” because I’m not a guy that sits around and writes just for the cathartic event of it. If Ray says we need a song, I’ll write one. If I’m hanging around Jake and he says “I need you to write me a song” … “No problem.” But I don’t have a whole backlog of material that I’ve been saving for years of stuff that I’ve written. Everything is made fresh.

Andrew:

The self-titled debut proved to be an immense success, but Voodoo Highway was released amid a distinct musical shift in 1991. How did the tour support for the album fare given the drastic changes?

Greg:

We didn’t have any tour support on Voodoo Highway because the record company was very mad at us, and Ray had done an interview kind of bagging on the record company for not supporting something that he wanted. He did it in a magazine, and they got wind of it and pulled our tour support. They told all the people at Atlantic [Records] in New York not to work the record. And we have enough support there from the separate A&R people there, that they were working the record on their own with the possibility of getting fired if they were found out. The record didn’t do bad — it did over 400,000 copies — and if we had tour support it would have done better. So, we put together our own tour; we had a booking agent and basically, me and the road manager advanced a whole tour, which is something I had never done. We came back from the first tour with no money; we came back from the Voodoo Highway tour with some money because we were actually in charge of our own destiny. So, two different ways of doing things — both were interesting — but it’s better to come home with money at Christmas time than no money.

Andrew:

Would you say it was around this time that the band began to splinter?

Greg:

Yeah, I mean there had been some issues. Ray was kind of looking for something — I think Ray knew he was sick at some point, and wanted to make a definitive statement. Ray’s favorite song and he would play it all the time, was “Shooting Star.” He would sing that song all the time, and near the end of his life, it made a lot of sense to me because if you listen to the lyrics in “Shooting Star,” they’re very similar to the way that Ray was kind of approaching his impending situation.

The record company hated us. We didn’t have a record deal at that point; we had people wanting to sign us. But there were obviously some issues. It’s sad because it was such a great band, and when it was kind of going sideways, I was sitting there on my own going, “Man, this is the best band of its time, and we can’t seem to hold it together.” And I think Jake was feeling the exact same thing. I saw an interview where he said that when Badlands broke up it broke his heart. And I’m kind of along the same lines as that.

The first record sold about 480,000 copies, so if Atlantic ever decided to release it, it would probably go gold the day it came out. Voodoo Highway sold about 420,000 [copies]. We got a gold record from Japan for both of them; Atlantic decided not to give us the second one. So, I have a gold record for the first one; there should be a gold record for the second one, but Atlantic decided probably to throw ‘em in the Hudson River, or something. I don’t know.

Andrew:

In 1994, you released a solo album, It’s About Time. What inspired you to pursue a solo career?

Greg:

I had been doing a lot of records for this label, Frontline, which is a Christian label, and they had heard me singing on a song. Their head of A&R came to me and said, “We’d like you to do a record.” And I said, “Can I have anyone I want on it?” And they said “Yes.” I said, “Can I do it in any direction I want?” And they said, “Yeah, whatever you want to do.” So, I decided to do this hard, bluesy Southern Rock — Johnny Winter meets Allman Brothers meets ZZ Top, and maybe some Humbie Pie. The only thing I didn’t like about it is, I hate my voice, but I had to sing on it. They paid me enough to make me happy to do it, but when I was recording it I went, “Oh, God I hate my voice.” People have always been very complimentary of it. They like it. But I can’t listen to it.

Andrew:

Years later, you and Jake ultimately reunited in his band, Red Dragon Cartel. Were you part of the band’s inception?

Greg:

No. Jake met a guy that had a studio and they wanted Jake to record there. The guy said, “You can record here for free as long as I play bass on it.” Well, he’s a guitar player, he’s not a bass player. So, Jake, I think got a deal with Frontiers and they did it. The guy — I can’t remember his name — I don’t think he played bass on every song. Then when the record came out, the first Red Dragon record, they were on tour with this guitar player playing bass, and Jake called me up and said, “We’re not digging this. We’re gonna play at Tempe, Arizona. Would you play bass at this show?” I said, “Yeah, sure.”

Jake and I hadn’t seen each other since the late 90s, and we got together and rehearsed. The first thing that we did was jam for 45 minutes on just whatever various riffs that Jake had. It was great; it was like we never missed a beat. Then I did the show with them, and then they asked if I would join the band. This was March of 2014. I had committed to working a baseball camp for little kids that I did every summer for about five years, from the end of May until August 1. I said, “I gotta do this camp, call me in August if you still want me to do it.” He called me and said, “You wanna do it?” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll do it.” I stayed with them until the spring of 2015 when I was diagnosed with cancer.

Quitting Red Dragon was hard because the plan for Jake, and I was to do Red Dragon until we just retired. But the other side of that is, I had had a band with Ryan and Jimi Taft — the drummer in the Atomic Kings — we had a band called Kings of Dust and we were getting ready to record. So, when I got done with my cancer treatment, it took me a couple of years ’til I was motivated, I finally called those guys and said, “Hey, let’s finish this record.” So, we went in the studio — and it had been going on, at that point, for five years – so we had a backlog of material, and Ryan and I wrote some new material as well. We went in the studio and made the Kings of Dust record, and put that out with the plan of going on tour. Well, the day our record came out was the day they declared a pandemic! So, when you talk timing, we have it in spades, I’m telling ya!

Andrew:

The initial incarnation of Kings of Dust has since morphed into the Atomic Kings. What spawned the birth of both projects?

Greg:

Well, the singer, and I and a guitar player got together to just basically do a couple of songs in the singer’s studio. Then throughout writing these three or four songs, we thought, “There’s something here.” After a year or so, the original guitar player, and drummer backed out, and the singer came to me and said, “I think the songs are good. Let’s keep doing it.” So, over the next couple years, we found Jimi Taft, our drummer, and Ryan — I was looking for a particular kind of guitar player; I wanted a very 70s kind of guy, and I wanted someone who understood what my influences were, and maybe someone that had the same kind of influences. The original guitarist, Mike, and I kind of had that going on, and I enjoyed that. That was the direction I wanted it to go in.

So, when I met Ryan — I’d actually seen him play one time and I thought, “He’s really good.” So, I called the guy up that I knew and I said, “There used to be a guitar player that played with this singer Scott Hammonds. I don’t know his name, but he had blonde hair, sang good, played good.” And he goes, “Oh, Ryan McKay.” I said, “Does he still live here in Arizona?” And he said, “Yeah.” And I said, “Can you get me his number?” He got me his number, and I called him up and I said, “Look, I got this project, I need a guitar player,” and I played him some of the material. He agreed to do it; it was kind of right up his alley.

Ryan McKay:

It was also a project that in that music I’ve made over the years — I’ve done more commercial stuff, Pop stuff — and one of the things I didn’t have in my small catalog was a big guitar record. Here I am guitarist, it’s my No. 1 thing, and this provided me an opportunity to have a record where it’s guitar-forward. There are lots of solos, long solos, and stuff like that. That was the main draw for me to take up that project. I thought it would be challenging, and Greg’s pretty fun to be around — despite what everyone says. [Laughs]. So, I knew it would be a wacky adventure, and it has for all these years now.

Greg:

I told [Ryan] when he got in the band, I said, “Listen, if you wanna play guitar solos, there are guitar solos — and they’re not these little, short, 30-second guitar solos. It’s like 16 bars of this, and then there’s gonna be a solo on the outside; there’s gonna be some fills and there’s gonna be this and that.” I said, “So, if you wanna state your case as a guitar player, I can help you.” And the songs are not your standard verse-chorus. Like I said earlier, this is like intros and two-and-a-half verses instead of two verses with a chorus and a bridge, and then the guitar solo is a separate section. Then there’s an outro. Some songs are between 4-6 minutes long and they’re kind of a musical adventure. I like what we do; I like how Ryan writes. It fits in very well with how I write because he has a little bit more of a Pop edge to him and I have a little bit more of a super heavy, kind of almost proggy, Hard Rock, Blues edge. And when you put it together, it makes for some interesting stuff. Then by the time you add Jimi on drums — Jimi is just a great drummer. Had Badlands stayed together, I would have submitted for him to be the third Badlands drummer.

So, we put out this record — we didn’t tour — we decided to write more songs rather than beat a dead horse with songs we had written over an 8-year period. Then along the way, we decided to fire our singer; things weren’t going the way that we wanted; things weren’t making sense anymore. There were some issues that we weren’t going to be able to overcome. I had done a project with Ken Ronk, who is the singer in Atomic Kings, and I liked his voice. He kind of has a little Paul Rodgers going on there; he has a little Mark Farner from Grand Funk. He definitely has a little bit of what Ray was into. He has a little [Robert] Plant in there. And for the way that Ryan and I were writing, we were even using more influences than we used on the first record, and Ken’s voice seemed to make a lot of sense. The very first song that he sang on, because he just comes in and we play, and I say, “Here’s a verse. Here’s a chorus. Here’s a bridge. What do ya got?” And right when he started singing, Ryan, Jimmy, and I looked at each other going, “Ah, that’s what’s been missing!” So, he was right in the groove; he’s a great frontman. In Arizona, he’s kind of like a local legend. Everyone knows him; everyone loves him. He’s the perfect addition/complement to what it is we do.

What happened was, the original singer got all bent out of shape and decided to sue us for the name Kings of Dust, which is stupid because it’s my name. I thought it up. And so, we sat around and talked about it and said, “You know what? Screw him. Let’s give him the name and we’ll change the name to Atomic Kings,” which is another name that I came up with and everyone liked it. That way it’s not the second Kings of Dust record, and you’re comparing one singer to the other. Now, it’s a new band — it’s Atomic Kings — with new material and a new singer. It’s starting from square one. We stand on our own. Obviously, all of us have done other things; I’m always gonna be compared to the stuff I did with Jake or with Steeler, or stuff I did for Mike Varney. But collectively, it is much stronger than Kings of Dust ever were, and the direction that we are going in is similar to what we were doing, but much bigger now. We’re bringing in much broader influences. We yuck it up quite a bit, they’re great guys, great players, and I couldn’t be happier.

Andrew:

And Ryan, by the way, it’s great to hear that you have an opportunity to tap into your prowess. It sounds like it’s going to be an optimal vehicle to showcase your talents.

Ryan:

Appreciate that. It’s been a challenge, and it’s always good, in anything you do, to push yourself and kind of set your boundary a certain way and be forced to where you’re gonna have to push through it. So, that’s always the fun part. Then, with the Crash Street Kids, I’ve always considered myself, not a guitar hero — I’m not that kind of a player — I’m more of a songwriter. That’s kind of how I looked at things.

Andrew:

What’s next for the Atomic Kings?

Greg:

We have a dozen songs written for this record we are going to record. I thought we were maybe going to record in December, but I think probably in January. We’ll record these eleven songs and nine of which will make the record and two will be bonus tracks here and there. Ryan and I decided to stop writing because we like everything we write and we don’t want to start taking stuff off the record to put other stuff on the record because we like it all too much. We’ll record on the first of the year, hoping for maybe a March-April release, and then depending on what goes on in this crazy country these days, we’ll try to head out and do some shows. There were several shows we were offered and some of them we even took out of state — including one in Sellersville — there is a festival we were going to co-headline out there but COVID kind of jammed everything up. So, hopefully by next summer when our record comes out, they’ll have a handle on what’s going on and we can go play. We’re going to play a show here in Phoenix — our first show ever — there’s a club here that has reconfigured its stage, so it’s a pretty nice setup. They’ve asked us to headline a date, and I think we’re gonna try to do that in January or early February. We’re looking forward to that; we’ve never actually played any of these songs live. We will play a smattering of material — three or four songs — from the Kings of Dust record. The bulk of the material will be from the new Atomic Kings record. It should be pretty groovy.

Andrew:

Before we go, I’d like to plug your store, if you’d like.

Greg:

The store in Phoenix is called Bizarre Guitar & Drum. We’re a 6,000 square foot store here. We probably got about 1,500 guitars in here; we don’t have any supply chain problem. And we’re also a drum dealer, as well. Pearl Drums and a bunch of other stuff. So, if you find yourself in the Phoenix area, Bizarre Guitar & Drums here in Midtown Phoenix, come out and see us.

Interested in learning more about the work of Greg Chaisson? Check out the links below:

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of Shredful Compositions, by Andrew DiCecco, here: https://vinylwritermusic.wordpress.com/shredful-compositions-archives/

Leave a Reply