All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

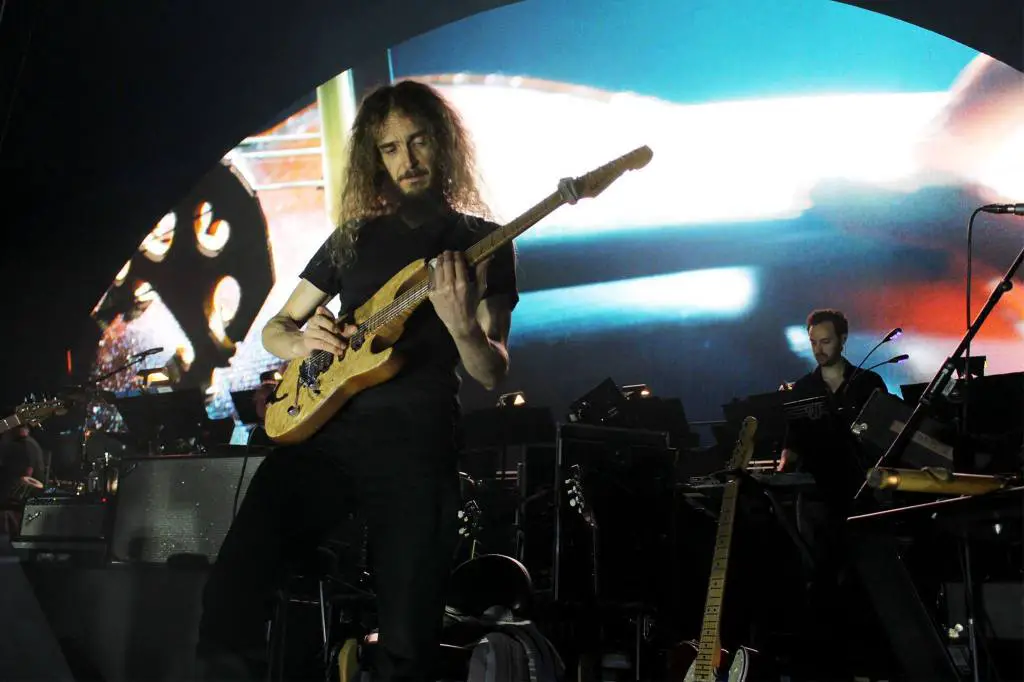

The Essex-born six-stringer runs through the many exploits of his varied career in this far-reaching interview.

By Andrew Daly

andrew@vinylwriter.com

The world of guitar is as deep as it is disparate. Well-traveled virtuoso Guthrie Govan perhaps knows this better than anyone as he’s lent his talents to sessions ranging from Asia to Jason Becker to Jordan Rudess to his fusion exploits.

Moreover, in the heterogeneous musical world we find ourselves in, few guitarists find such new and inventive ways to separate themselves from the pack. Still, for Govan, that endeavor has become a distinctive calling card. With an inherent ability to outright shred, paired with a nuanced feel for giving the song exactly what it needs every time out, few drive home their guitar-driven exploits better than Govan.

During a brief moment of peace amongst the chaos, Guthrie Govan took some time with VWMusic to recount his musical origins, working with Asia, lending his talents in the studio, and more.

What was the initial moment which first gravitated you toward music?

I couldn’t really pinpoint a specific moment. I grew up in a house where my parents very obviously derived a lot of enjoyment from their record collection. I must have absorbed a lot of their enthusiasm at an early age, so I came to regard music as something every bit as natural and omnipresent as the spoken word rather than as a discipline that needed to be “chosen” in any way.

Was there one singular event that led you to pick up the guitar?

Well, my dad had a cheap nylon string guitar lying around at home, and he would occasionally pick it up to play a rendition of a Beatles song or some such. I suppose growing up in that environment quickly led me to the “epiphany” that music was an important and powerful art form and something you could actually make yourself.

So, learning my dad’s limited chords vocabulary seemed like the world’s most natural thing. I honestly don’t remember how old I was when I first started to play, but people tell me I was about three years old. At that time, I suppose ’50s rock’ n’ roll would have been my primary influence: from the perspective of a beginner aspiring to learn a whole song from start to finish, those old I-IV-V classics certainly rank pretty highly in terms of sheer achievability. And the prospect of building a repertoire was a motivation for me at the time.

What were some of your earliest gigs?

I was five years old when I played in public for the first time. Some of my dad’s workmates had a rock ‘n’ roll band, and I remember being encouraged to guest with them at one of their gigs, playing some Elvis and Chuck Berry songs. It’s hard to imagine that I would have been playing particularly well all those years ago. Still, the audience seemed very supportive, so perhaps they just enjoyed the cute spectacle of a tiny five-year-old sharing the stage with a “grown-up” band.

The most important thing I took away from that whole experience was the notion of music as a form of communication. I loved the feeling that live performance was essentially an exchange of energy, where you “put something out there” and then get something back. That was a “lightbulb” moment for me, to be sure. I also appeared on U.K. national TV when I was nine years old; I played a rendition of “Purple Haze,” as I recall, with my younger brother Seth playing rhythm guitar. However, aside from the occasional random opportunity to do something exciting like that, I mostly felt like something of a weirdo and an outlier during that period; I wasn’t aware of any musically compatible kids in a similar age group until I reached my teenage years and somehow connected with some of the slightly older “metal” community at school.

When did you know you wanted to make music your profession?

The first time I realized that I was gigging regularly was during my time at university, where I somehow played a lot of jazz-funk. This would have been in the very early ’90s; acid jazz was very much the flavor of the month in the U.K. at that time, so any vaguely competent band in that stylistic ballpark could always find a gig in a place like Oxford University, which comprises 30-something different colleges, each with its own venue and entertainment budget. That was the first time I could play with any instruments outside the conventional “rock” world of guitar/bass/drums. I’m sure that getting a taste for trading solos with a sax player must have expanded my guitar-playing vision in some way; I had spent the previous few years focusing mainly on the more crazy/virtuosic aspects of rock playing but suddenly finding myself in a decidedly non-rock gigging scenario doubtless prompted me to wonder if some of that technical vocabulary might be applicable in a different context.

All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

One of your earliest gigs was with Asia. Take me through your indoctrination.

Towards the end of the ’90s, I was eking out a living primarily by transcribing for guitar magazines and teaching at the ACM academy in Guildford. At that time, the head of the ACM drum department was Mike Sturgis, who had played on some previous Asia recordings and was the band’s drummer of choice when they started work on the Aura album. As I understand it, the whole production was running way behind schedule, and some of the planned “celebrity” guest musicians wouldn’t be able to meet the recording deadline, so Mike kindly recommended me as an all-rounder who might be able to fill in all the guitar gaps at relatively short notice.

Aura and Silent Nation are two extremely underrated records in Asia’s discography. What did the writing process look like?

There really wasn’t much scope for me to contribute to the actual writing on those albums. Aura, in particular, felt like a project in which John Payne and Geoff Downes aspired to function as a kind of “melodic rock” version of the Donald Fagen/Walter Becker partnership, i.e., handling all of the writing/creative decisions themselves and then hiring whichever guest/session players might best help them to realize their ideas.

Silent Nation did feel a lot more like a traditional “band” album, and the lineup was much more consistent. Chris and I played drums and guitar on every track for that one, but the main songwriting input still came very much from John and Geoff. I suppose I may at least brought some fresh “guitar player” identity to those records. I initially came to Asia with the mindset of a session musician, striving to do whatever would make the band happy. Still, I gradually realized that my own “voice” on the instrument was perhaps a little more valued than I had initially assumed.

Prompted by your question about the band’s early work: if I revisit an album like Aura nowadays, I can certainly trace a thread of stylistic continuity back as far as the earliest John Payne-era albums, while, in contrast, Asia’s 1981 debut album somehow feels like something quite distinct from all the rest of the catalog, at least to my ears. Throughout my time working with John and Geoff, they certainly seemed open to the subtle incorporation of various new musical flavors, but, for the most part, I sensed that they were understandably reluctant to stray too far from the “signature” stylistic formula to which their fans had grown accustomed.

The lineup featured during that era, including Chris Slade, seemed to have wonderful chemistry. Can you expand on that a bit for us?

Prior to the Aura album, the band hadn’t done any touring for quite a few years. I think John and Geoff eventually found themselves in a situation where their writing partnership had become the only constant element in Asia’s personnel. The release of Aura felt very much like it was intended to accompany some triumphant re-launch for the band: all of a sudden, a lot of gigs were getting booked, and for the first time in years, Asia needed to be a viable touring entity with a stable lineup. I suppose that kind of “team” dynamic can generate positive energy, so perhaps some of that came across in the music? Those were certainly some fun times, at any rate.

What led to you moving on from Asia after the Silent Nation era?

Throughout my tenure in Asia, Geoff Downes was actually the only founder member in the lineup, so when all four of the original members were persuaded to get back together in early 2006 to mark the 25th anniversary of their first album, an awkward situation presented itself: all of a sudden, there were two different Asia’s, and of course, it wasn’t hard to guess which the general public would more enthusiastically receive one. The timing was also less than ideal; we were actually in the studio, recording what we were assuming to be the next Asia album-in-the-making, when Geoff announced to the rest of us that the reunion would be happening.

In an attempt to salvage a messy situation as best we could, the rest of us basically re-branded as GPS, recruiting Ryo Okumoto from Spock’s Beard to handle keyboard duties. We made an eponymous debut album under that name, and I think it turned out pretty well, given the circumstances. Still, the project undeniably seemed to lose a lot of momentum, and I suppose, gradually, it just became harder to justify persevering with it.

Erotic Cakes is one of my favorite albums out of all your work. Take me through its earliest hours.

That album owes its existence to Paul Cornford, the founder of Cornford Amps, which I was using/endorsing right up until the regrettable demise of the company. I had, of course, been writing weird instrumental guitar music for many years, so the bulk of the material was already there, but I never really had a solid business plan for releasing any of that stuff. So, it was through Paul’s encouragement and support that Erotic Cakes saw the light of day. He started a new record company for the sole purpose of bringing that one album into the world, and he also somehow conjured up the budget for all the guitar tracks to be recorded in Richie Kotzen’s L.A. studio, which was nice. Some of the material on Erotic Cakes had already existed in demo form for many years before the release of the album; songs like “Waves” and “Ner Ner” date back to my very late teens, as I recall. And “Wonderful Slippery Thing” was based on my entry for the 1993 Guitarist of the Year competition.

All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

You’ve explored your jazz-fusion side with The Aristocrats to beautiful results. Can you recount the band’s beginnings?

It’s interesting that you picked the term “jazz fusion.” Right from the very inception of the trio, we all agreed that we didn’t want to veer too far in that particular direction, although I freely admit that tracks like “Bad Asteroid” and “Get It Like That” clearly tip their hats to the genre. [Laughs]. To describe what we do to the press, we’ve pretty much settled on “rock-fusion” as the best description of our endeavors. We’re happy to highlight the spontaneous improvisational side of what we do, but we’ve always felt that our natural trio vibe has a slightly gritter/heavier “rock band” character.

At any rate, the formation of the Aristocrats was an entirely serendipitous affair. In 2011, Bryan [Beller] and Marco [Minnemann] had been booked to play a 30-minute trio performance at The Bass Bash – an annual fixture at the NAMM trade show in Anaheim, CA – and the guitar duties were initially meant to be handled by the very splendid Greg Howe. As luck would have it, some kind of unforeseen diary clash compelled Greg to pull out at the last moment, so Bryan started asking around frantically in the hope of finding a suitable replacement. I guess someone must have recommended yours truly, perhaps also pointing out that, conveniently, I was scheduled to be attending the NAMM show anyway? So, when I received the email from Bryan, I was, of course, more than happy to sign up for the gig.

The rest of the story goes like this: during our 30-minute Bass Bash mini-set, we discovered that we all seemed to share a kind of musical chemistry. All kinds of “telepathic” little connections seemed to keep firing between us as we played, even though our rehearsal time beforehand had been woefully limited. That kind of unplanned compatibility between musicians is rare, so right from the moment we walked off stage after the show, we all just knew that we wanted to explore that chemistry further.

The Aristocrat’s latest effort, You Know What… ?, continues your musical explorations. How has the band evolved since its debut?

When we made our first album, we did not know what kind of band we were. We were just three coincidentally like-minded musicians who evidently shared some musical connection and wanted to find out what we could do with it. Since then, it’s gradually become more apparent to us that we can get away with some fairly absurd and preposterous genre choices without compromising the overall band “sound,” so I suppose we’ve become bolder in our writing over the years. I feel like there has also been an organic evolution in specific terms of how we write music for each other: we know each other a lot better now, after hundreds of gigs, so I think each of us has a clearer sense of which ideas are most likely to work as Aristocrats songs.

Though certain things have remained constant through the band’s story: we’ve always aimed to be a democracy in all aspects of what we do as a trio, from how we approach business decisions to our long-standing tradition of contributing equally as composers. We also acknowledge that the way we play live is a massive part of our essence as a band, so even though we occasionally have fun with overdubbing and general studio-related naughtiness, we always try to bear in mind that the material we write is ultimately destined to be played on a stage, in real-time.

I wanted to touch on your work with Jason Becker and Jordan Rudess in 2018 and 2019. How did you become involved in the sessions?

Regarding Jordan: I guess you’re referring to the track “Off the Ground” from the Wired for Madness album. That was my second guest contribution to a Jordan Rudess album; I also played a solo on the “Screaming Head” track from the Explorations album in 2014. Anyhow, both of those remote recording assignments came about in the same way: Jordan just emailed me – he’s worked a lot with Marco, so that was the initial connection – to say that he had a new song and that he could imagine me playing something which might complement it. Will we collaborate further? Well, technically, I guess Jordan now owes me two keyboard solos, so perhaps it’s my turn to send him some unfinished music. [Laughs]. I’d love to hear how that might turn out. Well, one day, I guess, when the planets have aligned favorably.

Contributing to Jason Becker’s album was an intense and unique experience. The email/Dropbox mechanics of the collaborative process were, of course, much the same as they’ve been for any other guest solo I’ve recorded remotely. Still, emotionally, the mission just felt very different. It was impossible for me not to think about how great the track would have sounded in some kinder parallel universe in which Jason would have been able to play all the guitar parts himself, so I felt very conscious of not wanting to let him down. His musicianship and spiritual strength have been huge inspirations to me over the years.

All of that comes flooding back to me immediately whenever I relisten to the track, so hopefully, I captured something there. That solo certainly wasn’t the first take. [Laughs]. I should add that the Triumphant Hearts album as a whole truly felt like a veritable army of wonderful guitar players all rallying for Jason, so I was extra grateful for the invitation to be involved; the project seemed to generate a very special kind of positive energy.

My understanding is there is news to report there in the way of new music. Is that right?

Indeed! I think it’s fair to say that we didn’t entirely waste the lockdown period. Despite being trapped in different time zones, we still produced two “remote” albums: the Freeze! live record and our collaboration with the Primuz Chamber Orchestra, which turned out better than any of us could ever have imagined. Nonetheless, now feels like the time for us to get back to business as usual, so our next task is to get ourselves back into a studio and make a new trio album. We’re all busy writing material for that at this very moment, so we’re hoping to start recording early next year.

Will there be a tour to pair with the new music?

I think we all experienced some gigging withdrawal symptoms during the pandemic, so much like so many other bands right now; we’re currently making a serious effort to get our touring machinery up and running again. We just finished an epic 50-date tour of the US, and we already have all kinds of shows lined up for next year, starting with an Asian tour and then moving on to Europe.

Given the vast array of genres you’re associated with, which do you identify with most, and why?

I’d hesitate to pick a favorite, but, in general terms, I feel like I probably have the most to offer in a musical setting where I can do some spontaneous stuff and interact with other musicians in real-time. Perhaps this is the musical equivalent of preferring to have a conversation rather than delivering a prepared speech.

What’s next for you in all lanes, Guthrie?

In addition to next year’s Aristocratic shenanigans, I’ll also be doing a fair amount of touring with Hans Zimmer’s live band next year. Additionally: I’ve contributed notes and noises to several movie scores over the last few years, and this trend may continue. Though at this stage, I’m probably forbidden to elaborate further on that topic.

All images courtesy of Getty Images/Wiki Commons

– Andrew Daly (@vwmusicrocks) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at andrew@vinylwriter.com

Leave a Reply