“Jazz, rejected in its homeland, has had consciously to seek survival, conscientiously to explain and defend its existence’ and has been ‘variously banned and bullied” — McCombe

For many a listener of Jazz music, Free Jazz comes to one’s ears like some kind of exaggerated, and extremely dissonant disarranged sounds. But if you think about it, is this not what Jazz is supposed to do…play with dissonance and tension?

To some, Jazz music is seen as something created for the elites, difficult to understand, made for the elites, and as a result, the genre had much more difficulty to be recognized than what is generally known and referred to as Classical music, for the aforementioned reason — a persistent, racially motivated bias.

Jazz music’s nub is the Blues, a genre that was initially developed by slave workers in the Mississippi Delta area, who communicated via work songs that serviced as coded messages. Jazz, like many various genres, was born from the Blues, and it’s worth noting that most, if not all American music has at least some roots in Delta slavery camps.

As is the case with the Blues, one can say that Jazz music is also a narrative, a type of story, usually interpreted voicelessly — or might one say wordless. Instead, choosing to communicate with its listener via structure, harmony, and fixed chord changes.

The idea of breaking these rules was the trigger to what would come to be known as “Free Jazz.” It may have started with Ornette Coleman’s breaking these harmonic and structural conventions, later joining together John Carter and Bobby Bradford, whose experimental ideals got them to move to Los Angeles.

But before we dig deeper, first, we must understand the meaning of “experimental.”

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, “experimental” is used as an adjective to address something that is based on new ideas. Now, in the case of Jazz, these new ideas were applied as a means of breaking the chain of conventionalism that traditional Jazz music offered at the time. It was from Carter’s and Bradford’s studies on Bebop — and innovative genre in and of itself — that they started exploring the free improvisation focusing on melody, as well as giving melody the power to drive the tune; and from this exploitation they began their New Art Jazz Ensemble.

As for Coleman’s music, as Bradford had quipped, “It was more difficult to explain, but there are definitely some rules at work,” and these “rules,” loose as they may be, are what make Free Jazz a genre as opposed to cacophonic havoc of sound, and arrhythmic discordance. It was more about feeling the motioned through improvisation, but Bebop had lost this defining characteristic, and over the years had been dumbed down, and generally downplayed, which ultimately limited musicians. Fortunately, these musicians, as well as others, such as Charles Mingus and Eric Dolphy, set a trend in which the melody was the conductor of the song and not the fixed chords.

Or was there?

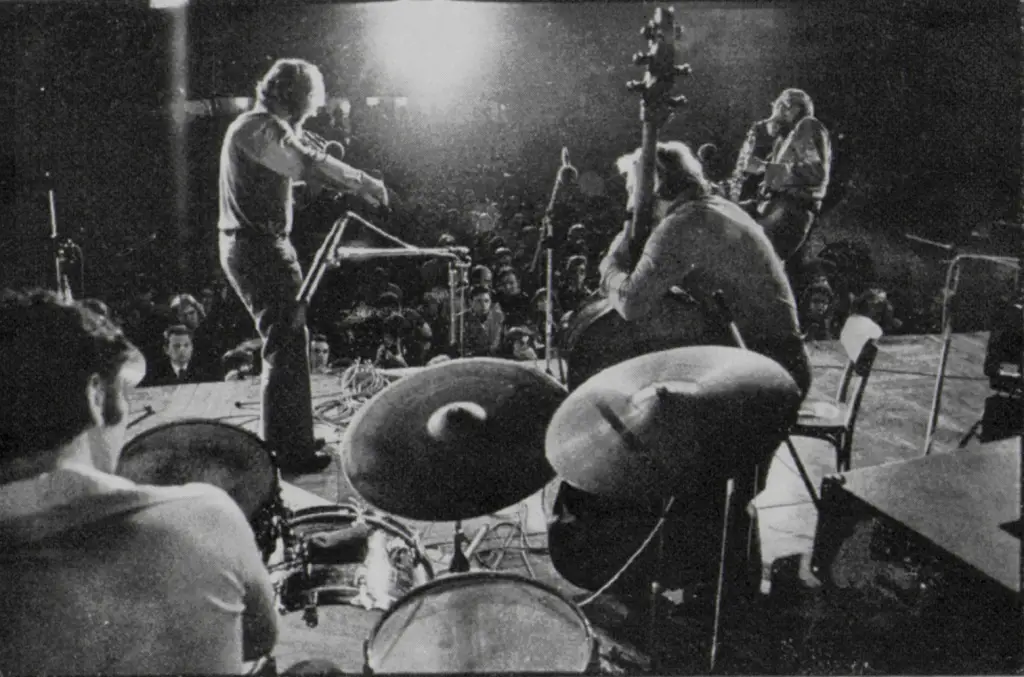

As Tom Williamson, the New Art Jazz Ensemble’s bassist, says, “The music kind of came once you get the head, but the thing was to get the head so precise, and together with that, the rest of it would take care of itself,” and much of their music followed this pattern.

In the words of Asia Johnson, “Free Jazz is unexpected. An experience. At times, a soloist. Other times, a big band. But only one voice…but never cold. She is never cold. Warm to the touch.” Although this non-structured genre may seem implausible to carry any positive effect on music, and more so on contemporary music, in the end, it did have some influence. All around the globe, some ensembles explore this facet of the freedom brought by Free Jazz, such as Jazz Fusion band, The Weather Report, Jazz pianists, Herbie Hancock, and the late, Chick Corea, amongst others, whose freedom gave way to a certain universality through improvised music.

What we can say for sure, is that Free Jazz made it possible to create music with no rules. Through this boundless genre, one can construct their own syntax, figuring it out on the spot, leading the band through means of melody, constant active listening, and contact with each band member.

Going again with the words of Asia Johnson, where each band member’s musicality leads the song, together, through, “Dark alleys. Winding paths.”

There…where one can become lost.

Dig this article? Check out the full archives of New Clew, by Fábio Moniz, here: https://atomic-temporary-187044500.wpcomstaging.com/new-clew-archives/

Leave a Reply