All images courtesy of Mach Bell. Not to be used without explicit consent.

By Andrew Daly

andrew@vinylwriter.com

Best known as the frontman for the late-stage era of the Joe Perry Project, “Cowboy” Mach Bell’s lineage runs far deeper than the average armchair rock devotee could ever imagine.

With early origins spent burrowed in the suburbs of the greater Boston area, Bell found himself a rock connoisseur in the wake of late 60s bred musical discovery, and before long, the aspiring singer was hitching a ride across the country, eyes fixed on The Golden State, with dreams of glitz, glam, and glitter swirling through his young, rock-drunk mind.

Upon reaching his destination, the young would-be vocalist became amazed, if not transfixed by all that The Sunset Strip had to offer. But soon, the golden embers of Bell’s dreams were cast with dull shades of gray, and it was with prospects slim, but imagery of grandeur still intact, that Bell set a course for home, and headed back east.

The term “underrated” is too often used, as is the term “great,”, especially in an age where rock fans’ collective thought process has been rewired to believe that “greatness” must coincide with chart success. It’s with this in mind that as Bell treaded on east coast soil once more, and triumphantly stepped into the spotlight as Thundertrain’s frontman, all that came after truly was great, if not wholly underrated.

With Thundertrain, Bell and his cohorts provided heroics across a vibrant New England scene, with now-extolized gigs at The Rat, coupled with infamous jaunts up and down the coast with The Dead Boys being some of the seminal cult act’s finest moments on stage.

Amongst the controlled chaos that was Thundertrain, following up their debut single, “Hot For Teacher,” the band recorded Teenage Suicide, an album comprised of fifty-seven minutes, and thirty seconds of outright, balls-to-the-wall rock, all of which are vital.

For many reasons, Thundertrain remained obscure, and when interband dynamics proved difficult, Bell jettisoned himself, literally running away to join the circus, before settling in for what he thought was a 9 to 5 future, when suddenly destiny called, this time in the form of former Aerosmith Les Paul buttress, Joe Perry.

With Perry, Bell’s task was mighty: carry the weight of not only the Aerosmith catalog but also Perry’s first two solo releases. And so, with zero studio time, label support, or fanfare, Bell hit the road with Perry and his revitalized band for a two and a half year wild ride, culminating in Bell’s only studio effort with Perry, Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker, before a sudden Aerosmith reunion halted things forever.

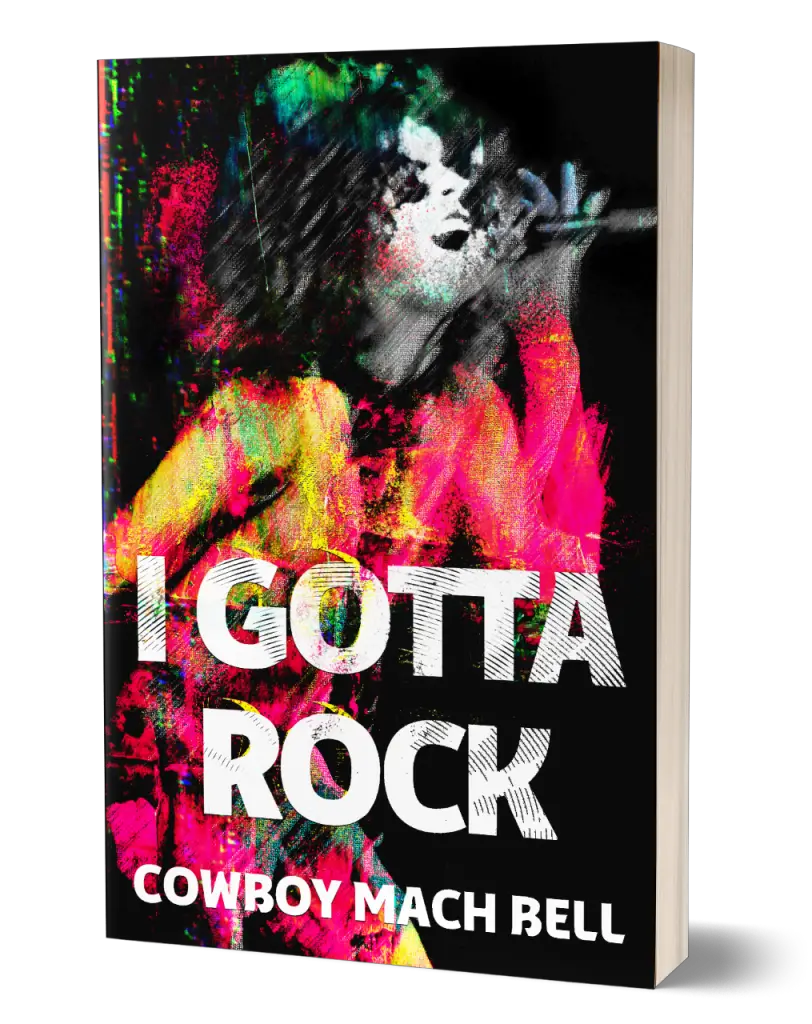

In the years since, Bell mostly laid low, until a twist of fate, and a pull of nostalgia saw Bell release his diary to the greater public as the well-received, Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker: A Diary. Bell’s literary foray was so well received, in fact, that he’s followed it up with another page-turner, I Gotta Rock.

I recently sat down with the erstwhile rocker to discuss his long journey through music, from the smallest bars in Bostin with Thundertrain, to some of the grandest stages in the world with Joe Perry, and everything in between.

Andrew:

Mach, thank you for taking the time. Walk me through your earliest memories of music in your life.

Mach:

Thank you for the invite, Andrew. My grandfather Nelson ran sound all over the eastern USA. When I was a little kid, he was renting Hammond organs to entertainers like Ray Charles. Together with my father, he ran the Music Box in Wellesley MA, focusing on high-end audio gear but selling stuff like TV sets and rock ‘n’ roll records too. As a pre-teen, I heard lots of cool Blue Note jazz and classical music my father liked. I went the classical route and studied the cello for four years.

Andrew:

Was there one singular moment that led you down the path of being a vocalist? If so, who were some of your earliest influences?

Mach:

The invention of the fuzz-tone inspired me to move from the cello to the electric guitar. I became proficient on rock guitar and was having some success – but needed a driving, ballsy vocalist to hitch my wagon to. The emergence of “rock singers” – I’m talkin’ guys like Jimi Hendrix, Keith Relf, James Brown, Ian Hunter, Jim Dandy, Little Richard, Noddy Holder, Jagger, Bob Dylan – guys who twisted and expanded on what the old-fashioned definition of what “a good voice” is supposed to sound like – those guys convinced me to become a rock singer.

Andrew:

As a New England native, paint a picture of the early scene you were exposed to, and some of your earliest gigs.

Mach:

Boston was the first port of call for the hard-rocking British blues groups. At age fifteen, I saw the Jimi Hendrix Experience play a tent here in suburban Framingham, MA. That was 1968 and the following year, I caught Led Zeppelin in the same tent venue. Robert Plant had just turned twenty the day before. It was the week after the Woodstock Festival and I got into Led Zeppelin for free, there were lots of empty seats to fill. “Father Frank” Connelly ran the tent and he would later manage the noteworthy local band, Aerosmith.

Andrew:

One of your earliest bands was The Mechanical Onions, which later was renamed the Cynics. What are the origins there?

Mach:

I was always searching for hard, raw, rock sounds on the Top-40 AM dial. We kids all lived with our portable transistor radios jammed up to our ears. Anyway, the heaviest sound of the moment was “I Had Too Much To Dream Last Night” by The Electric Prunes. So, Electric was akin to Mechanical, Prunes similar to Onions. Then we changed it to “The Effective.” “The Cynics” was next. Bold name choices for fourteen-year-olds. [Laughs].

Andrew:

At some point, you hitchhiked out to L.A., right? Walk me through that journey, and ultimately, what led you to come back to the east coast.

Mach:

Yeah. I followed the rock and if that meant hitching across America – that’s what I did. I’d thumbed teenage rides out to Boulder, Colorado where I met up with teen guitarist Tommy Bolin, and his band Zephyr. That was back in ’69. In ’74 I rode a hippie bus to San Francisco and hitched rides down to the Sunset Strip. The glitter scene was in full swing with the Sweet, Suzi Quatro, and Sable Starr all decked out at Rodney’s English Disco. Meatloaf and something called Rocky Horror Picture Show were playing live onstage at the new Roxy Theater. The action was intoxicating, but I had no connections to launch a band, nor a pot to pee in. I was at the payphone outside Turner’s Liquors when I got word that Ric Provost was putting together an outrageous, ballsy band back east.

Andrew:

Was Thundertrain back on your radar initially when you returned?

Mach:

Yeah, well Ric Provost and his brother Gene had been running “Doc Savage” out of a band house in Holliston. That act was the balls. They had a sexy, movie star-looking singer, an extra-long-limbed drummer, and Jimi on guitar – an excellent Hendrix clone. I guess the guys weren’t a DNA match – they ended up tearing each other to pieces – so Ric began recruiting new blood for his newest attraction – a band that would become Thundertrain.

Andrew:

From there, how did Thundertrain form? I read somewhere that “bands like Thundertrain are made, they’re born.” Can you elaborate on that sentiment for us?

Mach:

I spent years gaining stage experience playing guitar and singing back-up at Battle of the Bands, teen center, and town hall gigs with “Black Sun” and “Joe Flash and the Screamin’ Ya-Ya Girls.” At age twenty, I met future Thundertrain drummer Bobby Edwards, and he urged me to switch to lead vocals for his band “Biggy Ratt.” That was a major breakthrough. From there, Thundertrain came together in Boston during the scorching summer of 1974, just as Dick Nixon was being run out of the White House. Coming up, we were playing full-time, five hours of hard rock every night on the biker bar, and concert club circuit – Thundertrain was a brotherhood with bonds running deep. Back then, drummers didn’t moonlight with some other band…nobody had a “side project,” NO F’N WAY. [Laughs]. In those days, bands operated like a motorcycle club, and most of our business went unspoken. Music and gear were the focus at our band house (the Thundertrain Mansion), in the studio, and out on the road. Our souls were interwoven on a higher plane, and to this day, the surviving four Thundertrain members remain tightly connected on this out-of-body bandwidth.

Andrew:

Walk me through the writing and recording of “Hot For Teacher.”

Mach:

Our lead guitarist Steven Silva wrote it. He already had an album’s worth of stuff, but suddenly he saw this pulp paperback in a Combat Zone bookstore. It had that “Hot For Teacher” title, so he composed a Chuck Berry-type rocker around it. Jelly Records was a DIY indie label out of Lexington, MA. They were headed by soul-rocker Greg “Earthquake” Morton, and Jelly released “Hot For Teacher/Love the Way You Love Me” in spring 1976. It was the second Thundertrain 45 single and it immediately got lots of play on WBCN, the rock of Boston.

Andrew:

As I understand it, there is a Van Halen connection when it comes to Thundertrain. You were supposed to open for them in the late 70s, right? Did they borrow the title for their 1984 track of the same name?

Mach:

Thundertrain, Earthquake Morton, and our manager Allen Kaufman traveled to Cleveland, Ohio in the Summer of 1978. We had a great arrival party at Swingo’s and Kid Leo invited us up to WMMS-FM to promote our appearance at the Cleveland Agora the next night. Here’s how I heard it: Thundertrain management sent our promo pack to Van Halen management. “Hot for Teacher” was doing well regionally and got in the U.K. charts, so the single was part of the Thundertrain promo package. Van Halen apparently liked it, so Thundertrain was now in Cleveland, Ohio expecting to open for Van Halen. At the last minute, we discovered we’d be opening for Roadmaster instead of Van Halen. I kinda forgot about the whole mix-up until years later when I was touring with Joe Perry Project in Hollywood. Tower Records was next to our hotel on The Strip, so I walked over and bought the new Van Halen cassette, 1984, and was stunned to see our Thundertrain “Hot For Teacher” song title on the track listing.

Andrew:

Thundertrain cut its teeth around Boston and became a staple at the legendary Rat club. Take me through some of your earliest memories of Thundertrain on the live circuit.

Mach:

By the time we were a staple at The Rat, we were usually headlining bills with openers like Alan Vega Suicide, the Neighborhoods, Dead Boys, Mink Deville, Nervous Eaters, The Romantics, and The Cars. One time, Phil Lynott came onstage at The Rat and jammed with us, as Thin Lizzy had just finished opening at the Garden for Queen. Thundertrain would open for bands like David Johansen Group, The Runaways, and The Dictators, but my earliest memories of Thundertrain on the live circuit were different. We started out by copying glam bands Silverhead, Slade, Spiders From Mars, and T. Rex. Not only did we play really loud but we started out heavy on the glitter and face paint. We wanted to rile up the audience and create a scene. That tactic proved to be dangerous. So did the bomb we carried, and our DIY pyrotechnics caused problems too.

Andrew:

Teenage Suicide remains an enduring cult classic. What do you recall regarding its writing and reception?

Mach:

Teenage Suicide is unique. Thundertrain guitarists, Cool Gene Provost, and Steven Silva contributed the powerful songs, all rockers. I came up with the lurid “Teenage Suicide” title idea, and cover art concept, which was inspired by Michael Des Barres’ colorful Sixteen and Savaged Silverhead LP, but given a macabre twist. We went black and white, grainy, gruesome, both for shock value, and budgetary reasons. Jelly Records added to the fun with a big fold-out Thundertrain poster, and the initial run was stamped on clear vinyl – which collectors search for to this day. The original Jelly LP was picked up for national distribution, and it’s been re-released multiple times worldwide. Rolling Stone Magazine ignored us in the 70s, but decades later they favorably reviewed the CD re-issue of Teenage Suicide, calling Thundertrain, “The Guns N’ Roses of their time and place.”

Andrew:

In 1977, Thundertrain did a particularly memorable twelve-show run in New England and NYC with The Dead Boys. What memories do you have of those shows?

Mach:

My best, most lasting memories of all The Dead Boys, especially Stiv [Bators] happened off-stage. We cooked, ate, and roomed together at The Dead Boys apartment in the Bowery during our CBGBs co-bills. Stiv and his group used to camp out at my parents’ house when they came to Boston. I loved talking show business with Stiv. He’s another cat I’d consider a true “rock singer”- rather than just a great voice – Bators was a master of image, audience manipulation, and publicity. We talked for hours. Thundertrain would open on double-bills in NYC and The Dead Boys warmed up the crowd for Thundertrain on the Boston gigs.

Andrew:

What led you to walk away from Thundertrain?

Mach:

The usual feud between the lead guitarist (Steven Silva) and lead the singer (me) was part of it. By 1979, our band had been together for five years. Drummer Bobby Edwards and I went back even longer. Playing gigs constantly. The drinking age had been eighteen that whole time. Suddenly, it got yanked back up, and our young, core following got locked out of the clubs. FM radio was changing too. The dominance of the rock guitar was threatened by synths, computers, and layers of smooth FM-friendly stacked harmonies. People started talking about the “corporate rock” sound, along with prog rock, reggae, and disco. Thundertrain didn’t seem to fit in. Keep in mind, this was in the same weird time-warp in rock that saw Led Zeppelin end, KISS taking off their make-up, and Joe Perry quit Aerosmith.

Andrew:

From there, as I understand it, you’re working a “9 to 5,” and you get a call from Joe Perry. Take it from there.

Mach:

After Thundertrain broke up, I tumbled through a few other groups, “The Hits” and “Mag 4,” usually with my Thundertrain rhythm section. I ran away in early 1981 to join the circus. I began as a roustabout with Circus Vargas in Phoenix, AZ but worked my way up, eventually appearing in a couple of the animal acts. I didn’t stay with Vargas for long, the work was difficult and there were no days off. Our circus was touring through cities like San Diego and Los Angeles, the same towns I’d be visiting a year later, singing with the Joe Perry Project!

Andrew:

Walk me through the audition. How did Joe ultimately offer you the job?

Mach:

After I got fired from Circus Vargas, I decided to try the straight life. I took a job at the Music Box, the family business. That’s where Earthquake Morton called me with the news. He told me to come into the city and take over as lead singer with Joe Perry. He gave me five Joe Perry Project songs, and one Aerosmith hit to learn.

Andrew:

Were there any other notable names in the running?

Mach:

Charlie Farren told me there were a lot of guys competing for the singing spot at his Joe Perry Project audition a year earlier. There didn’t seem to be anyone else in the running at my audition. Basically, Joe needed a singer yesterday, and according to Earthquake, I was seen as the perfect fit. Joe’s manager Tim Collins was on board with Earthie’s idea from the beginning.

Andrew:

With two albums under his belt, and a cache of Aerosmith tracks as well, how did you go about adapting the material, and integrating yourself into the fold?

Mach:

That was my nightmare. Joe had worked with really good rock singers and producers before I came along. I was a different kind of performer, with a very different voice. Changing-out lead singers in an established rock act is tricky, but we’ve seen it work. Usually, though, the new singer, Sammy Hagar, Brian Johnson, or whoever, gets to make a new record with Van Halen or ACϟDC or whoever, with new songs, so the audience can absorb the changes before the tour actually hits town. Danny Hargrove and I replaced David Hull and Charlie Farren in the Joe Perry Project with no new record, no announcement, no photo, nothing. We were just shipped out on the road with nothing to prepare audiences for the different faces, sounds, and songs Joe would suddenly be playing. This went on for well over a year.

Andrew:

Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker remains your lone album with Joe. Walk me through the sessions.

Mach:

Our MCA record was released quite late in my two and half year tenure with Joe Perry. It took us over a year of touring and demoing to finally land the deal. By the time the record got made and into the stores, and by the time MTV began playing the video, I’d been singing anonymously with Joe for almost two whole years, and unbeknownst to me, The Project, our crew, and our management was about to morph into Aerosmith! We recorded right here in MA at Blue Jay Studios. Admiral Perry produced and directed, with help from Harry King. Joe had the band record all our tracks around his scratch guitar tracks. After Pet, Hargrove, and I finished our tracks, Admiral Joe spent a couple of weeks painting all the spaces in-between with his guitars.

Andrew:

Speak on your collaborative process with Joe, who reportedly was not in good shape mentally or physically at the time. How did the division of labor break down in terms of songwriting, lyrics, etc?

Mach:

Joe and I traded song title ideas back and forth from the beginning of our writing partnership. “Take a Walk With Me Sally” was a Joe Perry song title. Some of the titles would end up as lyrics like, “Give me another knife to juggle,” which is a Joe quote that ended up in “They’ll Never Take Me Alive” (unreleased). I wrote the lion’s share of the words and vocal melodies, and Joe Perry took care of the guitar parts and inspiration. The band arranged the songs that appear on Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker on the road, in front of paying audiences. My lyrics are based on the extensive travels and adventures of The Project – “Adrianna” (Caracas, VZ) or “4 Guns” West (Manatee County, FL, Cincinnati, OH, Austin, TX) – for starters.

Andrew:

Given Joe’s issues at the time, did he lean on his bandmates heavily around this time? Did his playing suffer?

Mach:

No, on both counts. True, our very first national tour was aborted early on when Admiral Perry passed out on stage in North Carolina. But after some rest and a few major adjustments, we returned to the road on July 4th,1982, and never missed another show from then on.

Andrew:

While the album didn’t sell well, it’s looked back on fondly. In your estimation, why didn’t the record hit? How was the label support? Had Joe been in a clearer headspace, do you feel the record would have fared better?

Mach:

In those first few months, the record reportedly sold forty thousand copies, which seemed amazing to me. At the time, I was broke, mooching off my girlfriend, and living in her apartment. I don’t think Joe Perry

even had a place to live at the time. The record was selling well, but at a moment when the record industry was greedily favoring real oil gushers. Selling thousands didn’t cut it – the suits were putting all their efforts into a few multi-million sellers. Hell, the Velvet Underground “banana peel” album, one of the most influential rock discs ever made, sold a total of 35,000 copies. Anyway, the Once a Rocker LP disappeared for ten years until MCA finally released a CD version in 1993. Then they sold our album through the Columbia House Record Club. In the end, they sold a ton of Once a Rocker albums, and they

still are. The rest is just a guessing game. Label support would have been great, MCA/Universal could have put a Joe Perry Project song into a Universal movie soundtrack, TV production, or budget a brilliant MTV video that would’ve launched a Joe Perry Project song into the top of the charts, but they didn’t.

Andrew:

What memories do you have of the tour which saw Brad Whitford join the band?

Mach:

Brad Whitford and I both boarded the Joe Perry Project pirate ship on the same day, February 26, 1982. I got to know Brad a bit during the next three weeks of daily rehearsal followed by a few days together in a recording studio, preceding our first live concert together. Besides Joe Perry and Brad Whitford, we also had original Project member Ronnie Stewart on drums, and my sidekick, bassist/vocalist Danny Hargrove, who joined the day before me.

Andrew:

You alluded to this a bit earlier, but did you feel the writing was on the wall for an inevitable Aerosmith reunion? Or did that development come as a shock? How did Joe break the news?

Mach:

Our newest member, drummer Joe Pet, and Danny Hargrove might have anticipated the Tyler/Perry reunion but it was a jarring surprise to me, and Joe never really said a thing about it to me. He left it to Tim Collins to drop the bomb.

Andrew:

After your time with Joe ended, you dropped off the radar. What led to that decision?

Mach:

My teeth and my overall health needed attention. My mind needed a change. After a few years singing with the Wild Bunch, I moved to Hollywood. I got an apartment on the Sunset Strip near Chateau Marmont, just across from the site of the old Pandora’s Box nightclub where the Riot on Sunset Strip erupted.

Andrew:

Moving forward, years later, you penned a book called Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker: A Diary. After so many years away, what led you to want to tell your story finally?

Mach:

I kept a daily diary of my adventures with the Admiral’s Project from day one. Starting from the phone call I got from Earthquake, asking me to, “Come down and sing with Joe Perry.” My diary covered every gig – 266 total – we played, every song we wrote, and every hotel we stayed in. All the fights and all the laughs too. My diary was being referenced in some Aerosmith books and started to get a reputation. I was shocked when San Francisco podcaster Michael Butler invited me onto his Rock ‘n’ Roll Geek Show in February 2019. At the close of a lengthy but funny/interesting interview, Michael urged me to publish my diary. Seven months later, Once a Rocker, Always a Rocker: A Diary became a book.

Andrew:

The book was well-received. Were you surprised at all?

Mach:

Yes. Very much so. I had a literary agent who briefly shopped my diary to the Big four. Some New York publishers liked the book, but nobody knew who I was or why it took me over thirty years to submit my manuscript, or why I had no Twitter following. So, I self-published Once a Rocker, which has turned out really well for me. I retain full control of my work and get worldwide online distribution through KDP/Amazon, Audible, and IngramSpark. Through the books, I’m reconnecting with Thundertrain and Joe Perry Project rock fans from all over the world. I’m also meeting new people, many are younger, and most are enthusiastic about my writing.

Andrew:

You have an additional book too, right? Tell us about it. What will this book cover that your first didn’t?

Mach:

Newly released is I Gotta Rock, my memoir of twenty years of rock from 1965 to 1985. Experiencing it. Living it. Doing it. Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck Group, the Boston Tea Party, underground Boston rock in the 60s, and 70s, following Aerosmith at the local dances and teen centers. The Thundertrain saga. Mid-70s rocking Max’s Kansas City, CBGBs, and The Rat. My popular Circus Vargas diary, and much more Joe Perry Project…with lots of photos. Never wanna stop!

Andrew:

Last one, Mach. Given the success of your two books, are you at all tempted to record new music, or dip your toe back into that world? What’s next?

Mach:

Yes. Here’s a scoop for you, Andrew. Mach Bell Experience. That’s the name of the hard-rock quartet I’m currently rehearsing with. Starting with a concert set of Thundertrain, and Joe Perry Project favorites. I’ll see where it goes from there. Stay tuned!

– Andrew Daly (@vwmusicrocks) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at andrew@vinylwriter.com

Leave a Reply