All images courtesy of Steve Conte

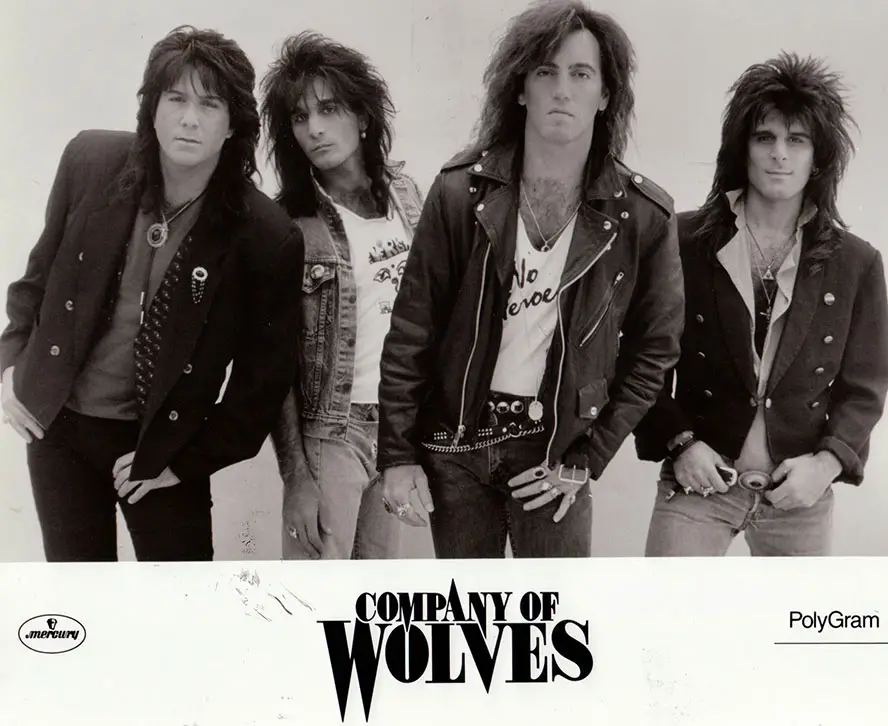

Steve Conte has held court with Company of Wolves, Crown Jewels, the Contes, New York Dolls, and Michael Monroe. In this far-reaching chat, we take a deep dive into the scene veteran’s long and influential career.

By Andrew Daly

andrew@vinylwriter.com

Over the decades, guitarist Steve Conte has impacted numerous seminal acts to sublime perfection.

Be it the New York Dolls, Michael Monroe’s solo ensemble, or an ever-bustling solo career, one thing is certain, Conte is a philosopher of all things guitar. In serving up buffets of musical perfection, Conte’s multi-layered, genre-defying approach to his instrument supplies listeners with fresh perspectives and, more importantly, damn good music.

If you managed to miss Conte’s former band’s Company of Wolves, Crown Jewels, or the Conte’s, you’ve got your marching orders for musical retrospection. But in the meantime, Conte’s latest record, Bronx Cheer, is available via his Bandcamp and across all streaming platforms. And, of course, Conte’s sweet licks can be heard via Michael Monroe’s music, too.

As he continues to scribble his musical signature across an evolving rock scene, Steve Conte took a moment with me to recount his history, his approach to the guitar, and what’s next for him as he moves forward.

What first drew you to the guitar?

At first, I was a drummer – at age 7. After hearing Ringo [Starr] on Revolver, I started taking drum lessons. But it was only after messing with my younger brother’s guitar when I was 11 that I realized I could write songs, having no idea what I was doing at all. I would strum with my fingernail instead of a pick and basically wrote bass lines on one string while singing melodies. I thought, “If I’m gonna sing and write songs, I can’t be stuck behind the kit at the back of the stage…” so I made the switch. And my brother switched to bass, which was the right choice for him as well because he’s one of the best.

What early life experiences shaped you as a musician?

My parents had a variety of great records in the house; the classics like Bach, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, etc., and loads of jazz and swing. Things like Sinatra, Tony Bennet, Ella Fitzgerald, Nancy Wilson, Wes Montgomery, Miles, Johnny Smith, etc. As for my own music, first, it was AM radio pop, Monkees, ’60s psychedelia, and folk music like Simon & Garfunkel and Bob Dylan. Later I would gravitate toward groups and songs I heard on the radio; Yardbirds, Who, Hollies, Small Faces, Beatles, and the Stones, of course. As for guitarists, the earliest stuff that turned me on was George Harrison on Beatles records – especially Revolver – Hendrix on Electric Ladyland, Page on Zeppelin II, and everything Chuck Berry.

How has your diversity as a player lent itself to the various gigs you’ve had over the years?

I’ve always described my style as smart pop with a New York garage attitude. [Laughs]. But if I hadn’t been so interested in learning about all kinds of music – not just rock – I wouldn’t be so diverse. Ever since taking my first lessons as a kid and then figuring out almost everything else in rock ‘n’ roll on my own, I’ve been on this path to know about what it is that I’m doing. I’ve always been a musical schizo, loving jazz, rock, funk, folk, blues, punk, new wave, flamenco, dub, reggae, fusion, soul, R&B, surf, rockabilly, etc. I always knew I’d pursue my own music but thought I should develop my “ear” and be able to communicate with other musicians, knowing what to call things in case I got a gig with someone else. And that came into play when I got calls to play my most meaningful gigs with two of my childhood heroes, Paul Simon, and Chuck Berry.

What are your memories of Company of Wolves’ early days?

We formed in NYC in 1988. I was playing residency with my brother and our blues band, The Hudson River Rats, at a club in the Village called Under Acme where many stars would come out to sing with us; Cyndi Lauper, Phoebe Snow, Carole King, Julian Lennon, and others, including singer Kyf Brewer. It was Jeff Kent, a mutual friend, who recommended I write songs with him, and on the first day, we wrote: “The Distance” and “Everybody’s Baby. “I said, “Hey, we should start a band; I know a bass player!” [Laughs]. It was my brother, John, of course, and Kyf had a drummer friend Frankie LaRocka who had played with Bryan Adams and John Waite and was working A&R at Atlantic Records.

Why did you choose to sign with Mercury Records?

After recording a few demos, Frankie got us a development deal at Atlantic records. They ultimately didn’t sign us, but we showcased for eight labels one night in early 1989 and went with Mercury, mainly because our manager was already working with them on Cinderella and KISS. We wore jeans, boots, leather jackets, and t-shirts but were caught up between the hair metal bands of the day and the bands we likened ourselves to; Georgia Satellites, Creedence, Stones, Cheap Trick, and early Aerosmith. We were told we could only get coverage in the metal mags and not in places like Rolling Stone. But eventually, when we got out there on tour, we met all these nice girls who owned clothing boutiques and would give us loads of stuff. So, we evolved from the dressed-down look to wearing skinny black jeans, tons of jewelry, purple and magenta, scarves, headbands, etc. We had a blast on our one-year US tour of clubs and arenas, touring with bands as disparate as Salty Dog and Richard Marx.

All images courtesy of Steve Conte

Do you feel Mercury supported Company of Wolves properly?

Before the ink was even dry on our deal, the label lost its president, so we were at a headless company. We had a great radio promo team and a good publicity department, but there was no one to steer the ship. Some bad biz decisions were made, but the friends we made there remain friends to this day. Great people. Regardless, being a new band with a hands-off type of manager plus no real strong direction from up high at the label, we were not in good shape there. And after our second record was completed, Nirvana had just hit, and everyone flocked to Seattle or toward that sound, so we couldn’t get the album out. We left the label and started our own bands, Kyf went his way, and the Conte Brothers went the other.

Crown Jewels made two excellent records. How did that group come together?

Since recording the Wolves’ demos in 1988, I started wanting to be the singer in my own band again. But it was complicated back then because we were trying to establish the band member’s roles and what was our lead singer gonna do while I sang one? Ever since I was a pre-teen, I was the lead singer in pretty much every band I had by default. Nobody wanted to sing; it was too hard. And singing, to me, is the embodiment of music because it’s a real connection to a song, a melody, a lyric. You can’t just let your fingers fly; you have to feel it and deliver. Somewhere along my journey, I became focused on guitar playing and thought I needed a partner, singer, and lyricist, a Mick to my Keef, a Plant to my Page if you will. But a year earlier, while demoing a song for a girl I was producing, I sang higher than I normally would, and voila! There was my voice, hiding in plain sight. So, I knew that my next band would be with me singing. I cut my teeth on singing Paul Rodgers, Rod Stewart, and Steve Marriott stuff during my teens, so the vibe was in there, just waiting to be unleashed. [Laughs].

Company of Wolves’ second record was released in 1998, the same year as Crown Jewels’ second effort. How did you balance the two?

It wasn’t difficult at all because it wasn’t a case of one band being out there on the road with a grueling schedule while the other one was sitting at home. We could easily record and release albums whenever we wanted. That’s one of the good things about the time we live in now. I record albums at home, pretty much.

What ultimately led to the end of Crown Jewels and Company of Wolves?

Company of Wolves ended when the Seattle scene came along, and we were not the flavor that labels wanted. We found out that the band wasn’t going to get re-signed with another label because we had run up too high a debt with Mercury for other labels to buy us out. We had to figure out ways to pay our NYC rent, and we all started doing studio work on other artists’ records. Me and Kyf did Billy Squier’s Tell The Truth album, film and TV soundtracks, commercials, publishing demos; whatever! Plus, I wanted to do my own thing, and my brother wanted to come with me because we had the same musical backgrounds; blues, hard rocking, jammy, soulful stuff, a la Stones, Zep, Humble Pie, and the Faces.

Crown Jewels ended because we went as far as we could in the indie scene, winning Best Unsigned Band competitions, playing music conferences, touring, getting radio play, etc. But we were the type of band, like the Wolves, who needed the support of a big label because we had radio songs. We weren’t a college, alternative, punk, garage, or cult band. We had mainstream material, but the timing wasn’t right, and it was exhausting doing everything myself, from the writing to the recording to the booking, touring, press, etc. So, I started taking guitar player gigs, first with Billy Squier, then Willy DeVille, and singing gigs with Paul Simon/ Simon & Garfunkel and Yoko Kanno, anime soundtracks, Cowboy Bebop, etc. And then came the Dolls.

I’m a huge fan of Bleed Together. Going in, what were your objectives for that record?

We had let go of the goal to get signed to a major label again and just wanted to make an arty record, the record we wanted to make, wearing all of our influences on our sleeve, from the power-pop Beatles side to the Americana singer-songwriter side to the weirdo lounge jazz and everything in between. It’s still my favorite record we ever made because it widened the scope of our talents; besides guitars and vocals, I play keyboards, bass, and arranged strings while John played guitar and sang lead vocals on two of his original songs. And to further not tie us down to a formula, there are four drummers on the album; Charley Drayton, Nir Z, Aaron Comes, and Rich Pagano.

All images courtesy of Steve Conte

What was the audition process for the New York Dolls like?

There was no audition! [Laughs]. Basically, David Johansen had asked around in respected NYC musician circles for a guitar player recommendation, and everyone he asked said the same thing: “Call Conte!” They told him not to bother with anyone else, that I had the right guitars and amps, the right hair, and a big nose. [Laughs]. He called me up, we met for lunch, talked, and at the end, he handed me an envelope with CDs, sheet music, and lyrics and said, “So whaddya think? Do you wanna do this?” And that was it. The next thing I knew, I was in a rehearsal room with Arthur ‘Killer’ Kane and Sylvain Sylvain working up the songs.

Were there any other notables in the running for the gig?

The only other person who I heard mentioned for the Meltdown reunion show was Joan Jett, but Johansen knew she would never be a long-term member if he ever needed one. And anyway, Joan’s a great performer, but she’s not really a lead guitarist.

How would you compare your era with the Dolls to the 70s heyday?

Fewer drugs and chaos, more mature personalities – no Crisis!- and the new band members were more seasoned musicians. Those are the obvious things, but there’s really no comparison to the original band. Those guys were like the Little Rascals of rock ‘n’ roll, just making it up as they went along, doing what felt good and right to them. The original Dolls were in their early 20s, and by contrast, me, Brian Delaney, and Sami Yaffa were closer to 40. When you get experienced players to play on a record, it’s not gonna be like their first recording session or first band, as it was for the original Dolls. All the members had made many records before the 2004 reunion, so we had a certain professionalism and dependability that hadn’t been there with the original lineup, David and Syl included! We were all more focused on the music and less on the freak show, which those guys had moved beyond, well into their 50s. Like Johansen said: “You can only be an amateur once.”

Did your experience with the Dolls affect your approach during the recording of Steve Conte & The Crazy Truth?

Oh yes! In fact, I was so inspired by that One Day It Will Please Us… recording session with Jack Douglas that I recorded my guitars exactly the same way; everything played live on the basic track, rhythm parts, and solos. And set up the same way; a stereo signal with two amps, my ’67 Marshall Plexi and ’62 Vox AC30 on most songs but on a few like “Gypsy Cab” and “Busload of Hope,” it was the Vox and my Ampeg Reverberocket for that vintage tremolo/reverb thing. I had been making cleaner, more lush-sounding albums with my bands on songs like “Linoleum” by Crown Jewels and “Bleed Together” by The Contes. But after that first Dolls reunion album, I found recording songs with a band that was on the edge of falling apart very exciting.

What led to you joining Michael Monroe?

Again, no audition; I was just called in to do it. After six years and four albums with New York Dolls, my reputation as a guitarist, singer, performer, and reliable band member was pretty secure. Sami recommended that Michael give me a call, and Michael also remembered meeting and playing with me when the Dolls toured Finland a year earlier. But the main reason I moved from the Dolls to Monroe was that the Dolls’ work was drying up, so I took some gigs with Michael. I tried to do both bands for a while, but when the Dolls’ management called with a plan to record a new album, the Monroe band already had a whole album written and ready to record. And the recording sessions were both scheduled for the same day, September 10, 2010, but theirs was in Blackpool, England, and ours was in Los Angeles. And so they got Syl’s pal Frank Infante from Blondie to play guitar, and the album’s producer, Jason Hill, played bass.

All images courtesy of Steve Conte

How have you most shaped Michael Monroe’s latter-day sound?

I think my guitar playing differs from anyone else he’s ever had. I’m not a “real” punk guy, and I’ve got no whammy bar. I don’t mean to sound snobbish, but with a background in jazz, things are gonna be a bit more harmonically sophisticated. Don’t get me wrong, he had some great players like Phil Grande and Jimmy Ripp, but when you write the songs, you get to put your musical stamp on them. I’ve been able to sneak in lots of nice chord voicings beyond the barre chord, power chord, and open-string cowboy chords. I think I did a lot of shaping in the vocal department, too, especially during the Horns and Halos sessions. On many of those songs I wrote for Michael, I would coach him on phrasing and pronunciation of English words and on singing more soulful melodies. I wasn’t giving him so many of the big dumb nursery rhyme/football chant kind of hooks to sing; they had a wee bit of “class.” Now we’ve gone back to football chant type of songs, which is fine, but Rich Jones also writes some very classy melodies.

What sort of gear do you use these days? Do you prefer vintage gear or new?

It depends on the situation; if I’m recording at my studio or another when home in NYC, I’ll use my vintage gear; 1967 Marshall Plexi, 1962 Vox AC30, 1959 Les Paul Junior, 1967 Telecaster, 1970 Les Paul, 1962 Stratocaster, 1972 Martin D-18 and other classics plus vintage pedals. That’s what I did for the New York Dolls’ One Day It Will Please Us… album, Steve Conte & The Crazy Truth, Bronx Cheer, a new record I just produced by Leather Catsuit and others. But when recording with Monroe in Finland or anywhere outside of the NY area, I will bring a couple of guitars that I don’t mind flying with – non-vintage ones – and whatever amps they have at that studio. The Monroe stuff isn’t about vintage or bluesy tones anyway; it’s nasty, aggressive punk rock, for the most part. And when we play live, like with the Dolls, I play the parts that need to be there, the guitar hooks or riffs that are recognizable and that define the song, and then where ever I can take liberties, I do.

If you had to choose one guitar to keep, which would it be?

Oh man, that’s such a tough one. It’s tough to pick because different guitars are perfect for different types of songs, and I really love them all. But I’d say I could cover all sounds needed on any record with just a Les Paul and a Telecaster. So, I can’t choose just one, but I can boil it down to two. [Laughs].

Are you working on new music?

I released the single “Gimme Gimme Rockaway” on Little Steven Van Zandt’s label, Wicked Cool Records, in 2017, then I released a number of solo tracks on my Bandcamp page along with a live acoustic EP and a Conte Brothers album in 2020. And there’s my latest album, which I’ve been promoting over the past year, called Bronx Cheer, which came out in 2021 on Wicked Cool Records. I am writing now with one of my songwriting heroes, I won’t say who yet, but it’s one of the thrills of my musical life. My next release will be different from the past bunch of albums. Not different than the music I love but different from what you’ve heard me do in recent years. I hope to get into the studio this fall to record the new album. Right now, I have studio time booked with Brian Ray, guitarist for Paul McCartney, to record a few songs we’ve written together. It’s no rest for the weary, mate. As Frank Sinatra said, “I’ll sleep when I’m dead.”

All images courtesy of Steve Conte

– Andrew Daly (@vwmusicrocks) is the Editor-in-Chief for www.vwmusicrocks.com and may be reached at andrew@vinylwriter.com

Leave a Reply